Literary Serialization in the 19Th-Century Provincial Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941 Colin Cook University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cook, Colin, "Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6734. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6734 BUILDING UNITY THROUGH STATE NARRATIVES: THE EVOLVING BRITISH MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939-1941 by COLIN COOK J.D. University of Florida, 2012 B.A. University of North Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 ABSTRACT The British media discourse evolved during the first two years of World War II, as state narratives and censorship began taking a more prominent role. I trace this shift through an examination of newspapers from three British regions during this period, including London, the Southwest, and the North. My research demonstrates that at the start of the war, the press featured early unity in support of the British war effort, with some regional variation. -

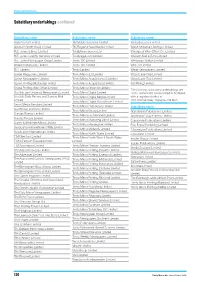

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

BUSINESS DIRECTORY of LONDON, 1884-Classijied Section PER Edi11burgh Guernsey Le"Igh, Lane • NORTH BRITISH ADVER Gazette Officielle De Guernesey & Leigh Chronicle

BUSINESS DIRECTORY of LONDON, 1884-Classijied Section PER Edi11burgh Guernsey Le"igh, Lane • NORTH BRITISH ADVER Gazette Officielle de Guernesey & Leigh Chronicle. D & J Forbes, props TISER & LADIES' JOUR The Guernsey Advertiser. Pub Liverpool NAL. Price ld. Estd 1826 lished on Saturday. The two • Liverpool Daily Post. Victoria st Elgin, N.B. largest circulated papers in the Llangollen ELGIN COURANT AND island. Prop. T l\I Bichard, Llangollen Advertiser (The) C 0 U R I E R. Amalgamated Bordage st Louth 18i4. Circulation 4,000 to 5,000. l-Iarldington, N. B, Louth Advertiser (Conservative). Only paper in Elgin. Best Haddingtonshire Courier. Friday,ld Largest circulation in the district. advertising medium for north lllllesworth Henry D Simpson pro. Esth 1859 eastern counties of Scotland. Spe Halesworth Times (W P Gale) Lyme Regis, Dorset cial features-agriculture, com Hllmmersmith, W Lyme Regis l\Iirror. Saturday l d merce, literature, shooting, fish 'Vest London Observer Broadway. Maccle.ifielrl ing, &c. Proprietors & publishers Established 1855, enlarged 1883. l\IACCLESFIELD COURIER nlack, \Valker & Grassie Exceeds by thousands the circ,Jla & HERALD (Conservative). Moray & Nain Express tion of anv• other "\Vest London Established 1809. Price 2d Erith nPwspaper Maidstone Erith Times. Sat ld. 43 Pier rd Hau•ick, N.B Kent Messenger & Maidstone Tele Eve sham Border Standard. YV ed mornings graph. 'V R & F Masters vroprs Evesham Journal. The only Eves HawickAdvertiser. Saturdaymorn South .Eastern Gazette Monday & ham paper, 8 pages ; very large ing<;. Established 1854 Saturday. F & H Cutbush proprs circulation through the Vale and Hawick Telegraph. Wed evenings liialton the Cotswolds. A first class agri Helensburgh l\Ialton Gaze:tte (Saturday) cultural district. -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office

GB0219XM 6233, XM2830 Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 37060 The National Archives GWYNEDD ARCHIVES AND MUSEUMS SERVICE Caernarfon Record Office Name of group/collection Group reference code: XM Papers of Mr. J.H. Roberts, AelyBryn, Caernarfon, newpaper reporter (father of the donors); Mr. Roberts was the Caernarfon and district representative of the Liverpool Evening Express and the Daily Post. He had also worked on the staff of the Genedl Gymreig and the North Wales Observer and Express. He was the official shorthand writer for the Caernarfon Assizes and the Quarter Sessions. Shorthand notebooks of Mr. 3.H. Roberts containing notes on: 'Reign of Common People' by H. Ward Beecher at Caernarvon, 20 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 21 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Borough Court, 23 Aug. 1886 Caernarvon Town Council (Special Meeting) 24 Aug. 1886. Methodists' Association at Bangor, 25-26 Aug. 1886 Quarrymen's Meeting, Bethesda, 3 Sept. 1886. ' Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 4 Sept. 1886 Bangor City Council, 6 Sept. 1886. Bangor Parliamentary Debating Society - Reports of Debates, 1886: Nov. 26 - Adjourned Queen's Speech. Dec. 10 - Adjourned Queen's Speech Government Inquiry at Conway to the Tithed Riots at Mochdre and other places before 3. Bridge, a Metropolitan magistrate. Professor 3ohn Rhys acting as Secretary and interpreter, 26-28 3uly, 1887. Interview with Col. West (agent of Penrhyn Estate, 1887). Liberal meeting on Irish Question at Bangor. 1 Class Mark XM/6233 XS/2830 Sunday Closing Commission at Bangor 1889. -

The University of Liverpool Racism, Tolerance and Identity: Responses

The University of Liverpool Racism, Tolerance and Identity: Responses to Black and Asian Migration into Britain in the National and Local Press, 1948-72 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Matthew Young September 2012 Abstract. This thesis explores the response of national and local newspapers to issues of race and black and Asian immigration in Britain between 1948 and 1972. Scholars have highlighted the importance of concepts of race, identity and belonging in shaping responses to immigration, but have not yet explained the complex ways in which these ideas are disseminated and interpreted in popular culture. The thesis analyses the complex role newspapers had in mediating debates surrounding black and Asian immigration for public consumption. By engaging with concepts of race and tolerance, newspapers communicated anxieties about the shape British culture and society would take in the postwar years. Their popularity granted them opportunities to lead attitudes towards black and Asian people and multiculturalism. The influences of social, political and cultural developments on both the national and local level meant newspapers often adopted limited definitions tolerance which failed to combat racism. In other cases, newspapers actively encouraged racist definitions of belonging which privileged their largely white audiences. In order to understand newspapers‘ engagement with concepts of race and identity, this thesis analyses the various influences that informed their coverage. While the opinions and ambitions of prominent journalists had a significant impact on newspaper policy, the thesis highlights the language and genres newspapers used to appeal to large audiences. -

Business Wire Catalog

UK/Ireland Media Distribution to key consumer and general media with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, news portals and Web sites via PA Media, the national news agency of the UK and Ireland. UK/Ireland Media Asian Leader Barrow Advertiser Black Country Bugle UK/Ireland Media Asian Voice Barry and District News Blackburn Citizen Newspapers Associated Newspapers Basildon Recorder Blackpool and Fylde Citizen A & N Media Associated Newspapers Limited Basildon Yellow Advertiser Blackpool Reporter Aberdeen Citizen Atherstone Herald Basingstoke Extra Blairgowrie Advertiser Aberdeen Evening Express Athlone Voice Basingstoke Gazette Blythe and Forsbrook Times Abergavenny Chronicle Australian Times Basingstoke Observer Bo'ness Journal Abingdon Herald Avon Advertiser - Ringwood, Bath Chronicle Bognor Regis Guardian Accrington Observer Verwood & Fordingbridge Batley & Birstall News Bognor Regis Observer Addlestone and Byfleet Review Avon Advertiser - Salisbury & Battle Observer Bolsover Advertiser Aintree & Maghull Champion Amesbury Beaconsfield Advertiser Bolton Journal Airdrie and Coatbridge Avon Advertiser - Wimborne & Bearsden, Milngavie & Glasgow Bootle Times Advertiser Ferndown West Extra Border Telegraph Alcester Chronicle Ayr Advertiser Bebington and Bromborough Bordon Herald Aldershot News & Mail Ayrshire Post News Bordon Post Alfreton Chad Bala - Y Cyfnod Beccles and Bungay Journal Borehamwood and Elstree Times Alloa and Hillfoots Advertiser Ballycastle Chronicle Bedford Times and Citizen Boston Standard Alsager -

Stillbirths: the Invisible Public Health Problem New Estimates Place Annual Global Toll at 2.6 Million Stillbirths

Stillbirths: The Invisible Public Health Problem New estimates place annual global toll at 2.6 million stillbirths Initial Media Report - April 17, 2011 News Wire Services Associated Press (Worldwide) Reuters (Worldwide) Reuters (Africa) Reuters Health E-Line Agence France Presse (Worldwide) United Press International (Worldwide) ANSA (Italy) (Worldwide) Inter Press Service (IPS) (Developing Countries) EFE News Service (Spanish Speaking Countries) The Canadian Press Press Association, UK Reuters Africa Africa Science News Service All Africa News South African Press Association (SAPA) The Pacific News Agency Service (PACNEWS), Australia Indo-Asian News Service, India Antara newswire, Indonesia AP Spanish Worldstream Agência Lusa, Portugal Agence France Presse – Chinese Pan African news agency (PANAPRESS), Africa Africa Science News Service (ASNS), Africa Reuters India AHN | All Headline News (Asia) IRIN News, Kenya Reuters América Latina, Latin America Newspapers & Magazines USA Today, USA The Washington Post, USA Los Angeles Times, USA Chicago Tribune, USA San Francisco Chronicle, USA Baltimore Sun, USA Chicago Sun-Times, USA Houston Chronicle, USA Sun Sentinel, USA El Nuevo Herald, USA Richmond Times Dispatch, USA Kansas City Star, USA San Antonio Express, USA The Republic, USA Miami Herald, USA Sun Herald, USA College Times, USA Macon Telegraph, USA Stamford Advocate, USA Westport-News, USA News & Observer, USA Greenwich Time, USA Palm Beach Post, USA Modesto Bee, USA Valley News Live, USA Albany Times Union, USA Charlotte Observer, -

Louise Tickle Looks at the Prevalence of Media Organisations and Other Groups Who “Expect Journalists to Work for Nothing

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | MAY-JUNE 2018 Full Stop. Ends... Young journalists flee newspapers for PR Contents Main feature 12 Are young dreams being dashed? Why new entrants leave journalism News id you dream of becoming a reporter 03 Al Jazeera strike over pay or an editor? Many of us did, attracted by an exciting career full of variety Protest over four-year wage freeze and the potential to hold power to 04 Bid to boost women’s media presence account. Campaign taken to Scottish TUC DBut, as Ruth Addicott finds in our cover feature, many young people are deserting these roles 05 More job cuts at Trinity Mirror not long after achieving them, finding that the reality of Digital drive rolls on clickbait driven, office-bound journalism today is not what 06 NUJ Delegate Meeting 2018 they dreamt of. Conference reports And then there’s the pay…or lack of it. Louise Tickle looks at the prevalence of media organisations and other groups who “expect journalists to work for nothing. Features Since the last edition of The Journalist the NUJ has held its 10 A day in the life of biennial delegate meeting – the policy setting framework for A union communications journalist the union. Low pay, worsening conditions at the BBC, Iran’s treatment of journalists on the BBC’s Persian service and many 12 Scoop other issues were on the busy agenda in Southport. International reporting then and now There was also a motion calling for The Journalist to remain a 16 Pay day mayday print publication published at least six times a year. -

Medical Diary for the Ensuing Week

1062 Friday, May 13. for ROYAL SOUTH LONDON OPHTHALMIC HOSPITAL.-Operations, 2 P.M. Medical Diary the ensuing Week. LONDON POST-GRADUATE COURSE.-Hospital for Consumption, Bromp. ton :4 P.M., Dr. Percy Kidd : Angina Pectoris.-BacteriologicaJl Laboratory, King’s College: 11 A.M. to 1 P.M., Professor Crookshank: Cultivation Methods (Examination of Cultivations).—Charing-cross Monday, May 9. Medical School: 8 P.M., Dr. J. Braxton Hicks: Funis Presentation and Prolapsus. ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL.-Operations, 1.30 P.M., and on Tuesday, CLINICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON.-8.30 P.M. Mr. F. Paul: A case of En. Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday at the same hour. terectomy.-Mr. Howard Marsh : A case of Spontaneous Cure of two ROYAL LONDON OPHTHALMIC HOSPITAL, MOORFIELDS.—Operations Aneurysms of the Femoral Artery, apparently by Inflammatory daily at 10 A.M. Action.-Dr. Francis Hawkins : A case of Non-tubercular Hæmo- ROYAL WESTMINSTER OPHTHALMIC HOSPITAL.-Operations, 1.30 P.M., ptysis of four months’ duration occurring in association with Arbuthnot Lane: Two cases of and each day at the same hour. Cirrhosis of the Kidneys.-Mr. Tubercular Disease of the Breast and Glands. CHELSEA HOSPITAL FOR WOMEN.-Operations, 2.30 P.M. ; Thursday, 2.30. Axillary HOSPITAL FOR WOMEN, SOHO-SQUARE. -Operations, 2 P.M., and on Saturday, May 14, Thursday at the same hour. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HOSPITAL.-Operations, 2 P.M. ; and Skin De. METROPOLITAN FREE HOSPITAL.-Operations, 2 P.M. partment, 9.15 A.M. ROYAL ORTHOPEDIC HOSPITAL.-Operations, 2 P.M. LONDON POST-GRADUATE COURSE.—Bethlem Hospital: 11 A.M., Dr. -

Proquest Dissertations

001214 UNION LIST OF NQN-CAiJADIAN NEWiiPAPLRJl HELD BY CANADIAN LIBRARIES - CATALOGUE CQLLECTIF DES JOURNAUX NQN-CANADIMS DANS LES BIBLIOTHEQUES DU CANADA by Stephan Rush Thesis presented to the Library School of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Library Science :. smtiOTHlQUS 5 •LIBRARIES •%. ^/ty c* •o** Ottawa, Canada, 1966 UMI Number: EC55995 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55995 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Dr» Gerhard K. Lomer, of the Library school of the Univ ersity of Ottawa. The writer Is indebted to Dr. W. Kaye Lamb, the National Librarian of Canada, and to Miss Martha Shepard, Chief of the Reference Division of the National Library, for their Interest and support in his project, to Dr. Ian C. Wees, and to Miss Flora E. iatterson for their sugges tions and advice, and to M. Jean-Paul Bourque for the translation of form letters from English into French, It was possible to carry out this project only because of Miss Martha Shepard1s personal letter to the Canadian libraries and of the wholehearted co-operation of librarians across Canada in filling out the question naires. -

United Kingdom Media List

UNITED KINGDOM MEDIA We will email your press release to the following UK news outlets. All media outlets have subscribed to our mailing list.We are C-spam compliant. Media pickup is not guaranteed. Oxford Mail London Evening Standard The Jewish Chronicle Financial Times Live Gloucester the citizen Stroud Gloucestershire Echo The Forester Gloucester the citizen Stroud The Leicester Mercury Shropshire Star Lancashire Evening Post Southern Daily Echo Rushpr News Hull Daily Mail Get SURREY Barnsley CHRONICLE Barnsley Chronicle Newark Advertiser Co Ltd Newark Advertiser Co Ltd Newark Advertiser Co Ltd Lynn News Bury Free Press Bury Free Press Express & Star Newbury today New The London Daily Chichester Observer bv media Blackmore Vale Magazine Abergavenny Chronicle The Abingdon Herald Independent Print Ltd The Irish Times EVENING STANDARD Metro the Guardian The Scotsman Publications Limited the times Mirror Daily Record Mansfield and Ashfield Chad The Bath Chronicle Belfast Telegraph Berwickshire News The Birmingham Post Border Telegraph Yorkshire Evening Post Daily Express Portsmouth NEWS Associated Newspapers Limited Scottish Daily Express Scottish Daily Mirror Daily Star of Scotland Daily Echo Western Daily Press Bucks Free Press & Times Group Archant The Cornishman Coventry Telegraph Derby Telegraph Carmarthen Journal Birmingham Mail The Bolton News Express & Star Blackburn Citizen The Liverpool Echo Chronicle & Echo Oldham Advertiser Mid Sussex Times The Chronicle Live Nottingham Post Media Group Peterborough Telegraph The Star The Press