Impact of Artificial Intelligence on IP Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers

Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers Easy access to local, regional and national news Quick Facts Features more than 25 newspapers from across Wales Includes the major dailies and community newspapers Interface in English or Welsh Overview Designed specifically for libraries in Wales, Access Wales & U.K. Newspapers features popular news sources from within Wales, providing in-depth coverage of local and regional issues and events. Well-known sources from England, Scotland, Northern Ireland are also included, further expanding the scope of this robust research tool. Welsh News This collection of more than 25 Welsh newspapers offers users daily and weekly news sources of interest, including the North Wales edition of the Daily Post, the Western Mail and the South Wales Evening Post. News articles provide detailed coverage of businesses, government, sports, politics, the arts, culture, finance, health, science, education and more – from large and small cities alike. Daily updates keep users informed of the latest developments from the assembly government, farming news, rugby and cricket events, and much more. Retrospective articles - ideal for comparing today’s issues and events with past news - are included, as well. U.K. News This optional collection of more than 500 news sources provides in-depth coverage of issues and events within the U.K. and Ireland. Major national broadsides and tabloids are complemented by a list of popular daily, weekly and online news sources, including The Times (1985 forward), Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Scotsman. This robust collection keeps readers and researchers abreast of local and national news, as well as developments in nearby countries that impact life in Wales. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Implementing Trinity Mirror's Online Strategy

Supplementary memorandum submitted by the NUJ (Glob 21a) Turning Around the Tanker: Implementing Trinity Mirror’s Online Strategy Dr. Andrew Williams and Professor Bob Franklin The School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University Executive Summary The UK local and regional newspaper industry presents a paradox. On “Why kill the goose the one hand: that laid the golden egg? [...] The goose • Profit margins are very high: almost 19% at Trinity Mirror, and has got bird flu” 38.2% at the Western Mail and Echo in 2005 Michael Hill, Trinity Mirror’s regional head of multimedia on the future of print newspapers • Newspaper advertising revenues are extremely high: £3 billion in 2005, newspapers are the second largest advertising medium in the UK But on the other hand: • Circulations have been declining steeply: 38% drop at Cardiff’s “Pay is a disgrace. Western Mail since 1993, more than half its readers lost since 1979 When you look at • Companies have implemented harsh staffing cuts: 20% cut in levels of pay […] in editorial and production staff at Trinity Mirror, and 31% at relation to other white collar Western Mail and Echo since 1999 professionals of • Journalists’ workloads are incredibly heavy while pay has comparable age remained low: 84% of staff at Western Mail and Echo think their and experience they workload has increased, and the starting wage for a trainee are appallingly journalist is only £11,113 bad”. Western Mail • Reporters rely much more on pre-packaged sources of news like and Echo journalist agencies and PR: 92% of survey respondents claimed they now use more PR copy in stories than previously, 80% said they use the wires more often The move to online Companies like Trinity Mirror will not be able to sustain high profits is like “turning based on advertising revenues because of growing competition from round an oil tanker […] some staff will the internet. -

The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941 Colin Cook University of Central Florida Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cook, Colin, "Building Unity Through State Narratives: The Evolving British Media Discourse During World War II, 1939-1941" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6734. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6734 BUILDING UNITY THROUGH STATE NARRATIVES: THE EVOLVING BRITISH MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939-1941 by COLIN COOK J.D. University of Florida, 2012 B.A. University of North Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 ABSTRACT The British media discourse evolved during the first two years of World War II, as state narratives and censorship began taking a more prominent role. I trace this shift through an examination of newspapers from three British regions during this period, including London, the Southwest, and the North. My research demonstrates that at the start of the war, the press featured early unity in support of the British war effort, with some regional variation. -

News Consumption Survey 2019

News Consumption Survey 2019 Wales PROMOTING CHOICE • SECURING STANDARDS • PREVENTING HARM About the News Consumption report 2019 The aim of the News Consumption report is to inform understanding of news consumption across the UK and within each UK nation. This includes sources and platforms used, the perceived importance of different outlets for news, attitudes towards individual news sources, international and local news use. The primary source* is Ofcom’s News Consumption Survey. The survey is conducted using face-to- face and online interviews. In total, 2,156 face-to-face and 2,535 online interviews across the UK were carried out during 2018/19. The interviews were conducted over two waves (November & December and March) in order to achieve a robust and representative view of UK adults. The sample size for all adults over the age of 16 in Wales is 475. The full UK report and details of its methodology can be read here. *The News Consumption 2019 report also contains information from a range of industry currencies including BARB for television viewing, TouchPoints for newspaper readership, ABC for newspaper circulation and Comscore for online consumption. PROMOTING CHOICE • SECURING STANDARDS • PREVENTING HARM 2 Key findings from the 2019 report • TV remains the most-used platform for news nowadays by adults in Wales at 75%, compared to 80% last year. • Social media is the second most used platform for news in Wales (45%) and is used more frequently than any other type of internet news source. • More than half of adults (57%) in Wales use BBC One for news, but this is down from 68% last year. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of BMJ Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of BMJ stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. This week’s (8-14 May) highlights: ● A study in The BMJ reporting heightened risk of heart attacks with common painkillers generated global news headlines, including BBC, CNN and Voice of America ● A rapid recommendations article in The BMJ, advising against surgery for most patients with knee arthritis also made global headlines, including CBS and National Public Radio (NPR) in the US ● A warning by doctors in BMJ Case Reports of parasites in raw and undercooked fish generated global headlines, including BBC, Newsweek, CNN and Hindustan Times ● Dr Krishna Chinthapalli was interviewed on Channel 4 News, Sky News, and BBC about this weekend’s cyberattack after warning in The BMJ that hospitals must be better prepared The BMJ Awards Birch's life-saver wins a top award [print only] - Leicester Mercury, 10/05/2017 The BMJ Analysis: Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit Fluctuating emotions are part of sport, they must not cloud mental health debate - The Times + The Times Scotland [The Game] 08/05/2017 Trump, the doctor and the vaccine scandal [mentions The BMJ’s articles accusing Andrew Wakefield of fraud] - Channel 4 Dispatches 08/05/2017 Why on earth are so many broken bones not spotted in casualty? - Daily Mail -

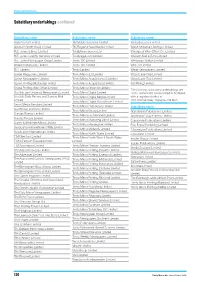

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

BUSINESS DIRECTORY of LONDON, 1884-Classijied Section PER Edi11burgh Guernsey Le"Igh, Lane • NORTH BRITISH ADVER Gazette Officielle De Guernesey & Leigh Chronicle

BUSINESS DIRECTORY of LONDON, 1884-Classijied Section PER Edi11burgh Guernsey Le"igh, Lane • NORTH BRITISH ADVER Gazette Officielle de Guernesey & Leigh Chronicle. D & J Forbes, props TISER & LADIES' JOUR The Guernsey Advertiser. Pub Liverpool NAL. Price ld. Estd 1826 lished on Saturday. The two • Liverpool Daily Post. Victoria st Elgin, N.B. largest circulated papers in the Llangollen ELGIN COURANT AND island. Prop. T l\I Bichard, Llangollen Advertiser (The) C 0 U R I E R. Amalgamated Bordage st Louth 18i4. Circulation 4,000 to 5,000. l-Iarldington, N. B, Louth Advertiser (Conservative). Only paper in Elgin. Best Haddingtonshire Courier. Friday,ld Largest circulation in the district. advertising medium for north lllllesworth Henry D Simpson pro. Esth 1859 eastern counties of Scotland. Spe Halesworth Times (W P Gale) Lyme Regis, Dorset cial features-agriculture, com Hllmmersmith, W Lyme Regis l\Iirror. Saturday l d merce, literature, shooting, fish 'Vest London Observer Broadway. Maccle.ifielrl ing, &c. Proprietors & publishers Established 1855, enlarged 1883. l\IACCLESFIELD COURIER nlack, \Valker & Grassie Exceeds by thousands the circ,Jla & HERALD (Conservative). Moray & Nain Express tion of anv• other "\Vest London Established 1809. Price 2d Erith nPwspaper Maidstone Erith Times. Sat ld. 43 Pier rd Hau•ick, N.B Kent Messenger & Maidstone Tele Eve sham Border Standard. YV ed mornings graph. 'V R & F Masters vroprs Evesham Journal. The only Eves HawickAdvertiser. Saturdaymorn South .Eastern Gazette Monday & ham paper, 8 pages ; very large ing<;. Established 1854 Saturday. F & H Cutbush proprs circulation through the Vale and Hawick Telegraph. Wed evenings liialton the Cotswolds. A first class agri Helensburgh l\Ialton Gaze:tte (Saturday) cultural district. -

7 Shocking Local News Industry Trends Which Should Terrify You

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / The Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Newyddiaduraeth Newyddion yng Nghymru / News Journalism in Wales CWLC(5) NJW10 Ymateb gan Dr. Andy Williams, Prifysgol Caerdydd / Evidence from Dr. Andy Williams, Cardiff University 7 shocking local news industry trends which should terrify you. The withdrawal of established journalism from Welsh communities and its effects on public interest reporting. In the first of two essays about local news in Wales, I draw on Welsh, UK, and international research, published company accounts, trade press coverage, and first-hand testimony about changes to the economics, journalistic practices, and editorial priorities of established local media. With specific reference to the case study of Media Wales (and its parent company Trinity Mirror) I provide an evidence-based and critical analysis which charts both the steady withdrawal of established local journalism from Welsh communities and the effects of this retreat on the provision of accurate and independent local news in the public interest. A second essay, also submitted as evidence to this committee, explores recent research about the civic and democratic value of a new generation of (mainly online) community news producers. Local newspapers are in serious (and possibly terminal) decline In 1985 Franklin found 1,687 local newspapers in the UK (including Sunday and free titles); by 2005 this had fallen by almost a quarter to 1,286 (Franklin 2006b). By 2015 the figure stood at 1,100, a 35% drop over 30 years, with a quarter of those lost being paid-for newspapers (Ramsay and Moore 2016). -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office

GB0219XM 6233, XM2830 Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 37060 The National Archives GWYNEDD ARCHIVES AND MUSEUMS SERVICE Caernarfon Record Office Name of group/collection Group reference code: XM Papers of Mr. J.H. Roberts, AelyBryn, Caernarfon, newpaper reporter (father of the donors); Mr. Roberts was the Caernarfon and district representative of the Liverpool Evening Express and the Daily Post. He had also worked on the staff of the Genedl Gymreig and the North Wales Observer and Express. He was the official shorthand writer for the Caernarfon Assizes and the Quarter Sessions. Shorthand notebooks of Mr. 3.H. Roberts containing notes on: 'Reign of Common People' by H. Ward Beecher at Caernarvon, 20 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 21 Aug. 1886. Caernarvon Borough Court, 23 Aug. 1886 Caernarvon Town Council (Special Meeting) 24 Aug. 1886. Methodists' Association at Bangor, 25-26 Aug. 1886 Quarrymen's Meeting, Bethesda, 3 Sept. 1886. ' Caernarvon Board of Guardians, 4 Sept. 1886 Bangor City Council, 6 Sept. 1886. Bangor Parliamentary Debating Society - Reports of Debates, 1886: Nov. 26 - Adjourned Queen's Speech. Dec. 10 - Adjourned Queen's Speech Government Inquiry at Conway to the Tithed Riots at Mochdre and other places before 3. Bridge, a Metropolitan magistrate. Professor 3ohn Rhys acting as Secretary and interpreter, 26-28 3uly, 1887. Interview with Col. West (agent of Penrhyn Estate, 1887). Liberal meeting on Irish Question at Bangor. 1 Class Mark XM/6233 XS/2830 Sunday Closing Commission at Bangor 1889. -

Newspapers (Online) the Online Newspapers Are Available in “Edzter”

Newspapers (Online) The Online Newspapers are available in “Edzter”. Follow the steps to activate “edzter” Steps to activate EDZTER 1. Download the APP for IOS or Click www.edzter.com 2. Click - CONTINUE WITH EMAIL ADDRESS 3. Enter University email ID and submit; an OTP will be generated. 4. Check your mail inbox for the OTP. 5. Enter the OTP; enter your NAME and Click Submit 6. Access EDZTER - Magazines and Newspapers at your convenience. Newspapers Aadab Hyderabad Dainik Bharat Rashtramat Jansatta Delhi Prabhat Khabar Kolkata The Chester Chronicle The Times of India Aaj Samaaj Dainik Bhaskar Jabalpur Jansatta Kolkata Punjab Kesari Chandigarh The Chronicle The Weekly Packet Agro Spectrum Disha daily Jansatta Lucknow Retford Times The Cornishman Udayavani (Manipal) Amruth Godavari Essex Chronicle Kalakamudi Kollam Rising Indore The Daily Guardian Vaartha Andhra Pradesh Art Observer Evening Standard Kalakaumudi Trivandrum Rokthok Lekhani Newspaper The Free Press Journal Vaartha Hyderabad Ashbourne News Financial Express Kashmir Observer Royal Sutton Coldfield The Gazette Vartha Bharati (Mangalore) telegraph Observer Ayrshire Post First India Ahmedabad Kids Herald Sakshi Hyderabad The Guardian Vijayavani (Belgavi) Bath Chronicle First India Jaipur Kidz Herald samagya The Guardian Weekly Vijayavani (Bengaluru) Big News First India Lucknow Leicester Mercury Sanjeevni Today The Herald Vijayavani (Chitradurga) Birmingham Mail Folkestone Herald Lincoln Shire Echo Scottish Daily Express The Huddersfield Daily Vijayavani (Gangavathi) Examiner