A Narrative Case Study Simon Shaw. the University of Melbourne, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIA ORA SITE CONCEPT PLAN Prepared for Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service

KIA ORA SITE CONCEPT PLAN prepared for Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service KIA ORA SITE CONCEPT PLAN prepared for Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services Inspiring Place Pty Ltd Environmental Planning, Landscape Architecture, Tourism & Recreation 210 Collins St Hobart TAS 7000 T 03 6231 1818 E [email protected] ACN 58 684 792 133 20 January 2021 Draft for PWS review 01 February 2021 V2 for PWS review 09 March 2021 V3 for PWS CONTENTS Section 1 Background .................................................................... 1 Section 2 Site Concept Plan ..................................................... 9 2.1 Planning and Policy Context .................................................................... 9 2.2 The Site Concept Plan .............................................................................. 15 2.2.1 Kia Ora Hut .............................................................................................................. 18 2.2.2 Toilets ......................................................................................................................... 21 2.2.3 Ranger Hut .............................................................................................................. 22 2.2.4 Tent Platforms ....................................................................................................... 22 2.2.5 Rerouting the Track ......................................................................................... 23 2.2.6 Interpretation ...................................................................................................... -

Wildtimes Edition 28

Issue 28 September 2006 75 years old and the Overland Track just gets better and better! The Overland Track is Australia’s most popular long-distance walk, with about 8,000 to 9,000 people making the trek each year. It’s a six- day walk travelling 65 kilometres through the heart of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and it has earned an international reputation among bushwalkers. In recent years the growing popularity of the In this issue track has resulted in increased visitor numbers, leading to unsustainable environmental and – Celebrate 1997-2007 social pressures. Systematic monitoring by staff – New Editor and WILDCARE Inc volunteers noted increasing – New web site crowding at some campsites along the track, as The difference between previous years and this – KarstCARE Report well as overcrowding at huts, with as many 130 season (summer 2005/ 2006) was remarkable. people a night at one location. – Walking tracks in National Walkers, WILDCARE Inc volunteers and Parks Parks upgraded In June 2004, the vision for the Track was staff all enjoyed fewer crowds. While the total announced: The Overland Track will be – PWS Park Pass forms numbers of walkers using the track were similar Tasmania’s premier bushwalking experience. A to previous years, the difference was that the – Board Meetings key objective for management was to address flow of walkers was constant, rather than the – Group Reports the incidence of social crowding and to provide peaks and troughs of past seasons. – Tasmanian Devil Volunteers a quality experience for walkers. Volunteers have played a large part in the – David Reynolds - Volunteer Three key recommendations would drive the success of implementing the new arrangements Profile implementation of the vision: a booking system on the Overland Track. -

Kia Ora Hut and Toilet Replacements Name of Reserve

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REPORT Kia Ora Hut and KiaToilet Ora Replacement Hut and ToiletName of Reserve Replacements Overland Track Cradle Mountain Lake St Clair National Park. RAA 3883 July 2021 Published by: Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 1751 Hobart TAS 7001 Cite as: Parks and Wildlife Service 2021, Environmental Assessment Report for Reserve Activity Assessment 3883 Kia Ora Hut and Toilet Replacement, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. ISBN: © State of Tasmania 2021 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment 2 PWS Environmental Assessment Report – Kia Ora Hut and Toilet Replacement Environmental Assessment Report Proponent Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) Operations Branch, North West Region Proposal Kia Ora Hut and Toilet Replacement Location Kia Ora overnight node, Overland Track (OLT) Reserve Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park RAA No. 3883 Document ID Environmental Assessment Report (EAR) – Kia Ora Hut and Toilet Replacement – July 2021 Assessment type Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Level 3, Landscape Division Related initiatives Overland Track Hut Redevelopment Project Kia Ora Site Concept Plan 2021 Waterfall Valley Hut Redevelopment Reserve Activity Assessment (RAA) 3465 Windermere Hut, Toilet and Group Platform RAA 3744 Contact Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service GPO Box 1751 Hobart Tasmania 7001 1300 TASPARKS (1300 827 727) www.parks.tas.gov.au RAA 3883 EAR 3 Contents Glossary and -

TWWHA Master Plan Final V3 4 Sept 20.Indd

DPIPWE - Tourism Master Plan for the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Final draft RELEASE 4 September 2020 - DL - RTI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment commissioned ERA Planning and Environment to lead a multidisciplinary team to develop the Tourism Master Plan and who have in collaboration with the Department prepared this document. The team comprises: ERACONTACT Planning DETAILSand Environment (principal consultant) Master planning Cultural Heritage Management Australia ParksCultural and values Wildlife and AboriginalService community engagement GPO Box 1751 Hobart,SGS Economics Tasmania, & Planning 7001 Economic, tourism and visitation analysis Noa1300 Group TASPARKS (1300 827 727) Initial engagement facilitators www.parks.tas.gov.au Hit Send DPIPWE Editors - RELEASE - DL - RTI Front photo credit: Joe Shemesh DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT The area of country that is encompassed in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area is Aboriginal land. In fact, the whole island of Lutruwita/Tasmania is Aboriginal land. Our sovereignty was not, and never will be, ceded. Aboriginal people have been in Lutruwita since the beginning of time; our stories of creation tell us that. We are more than simply ‘custodians’ or ‘caretakers’.DPIPWE We are the land, country, and she is- us. For many, many generations we have cared for our country, and coexisted with plants, animals, birds and marine life, taking only what was needed to sustain us. We remember and honour -

Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley

Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley 4 h to 6 h 5 10.8 km ↑ 535 m Very challenging One way segment ↓ 384 m The Overland Track starts by guiding you through some amazingly diverse and spectacular landscapes. You start from the bus stop and car park at Ronny Creek, then wander for a few hundred meters through the buttongrass plains beside Ronny Creek. After this the uphill starts, it is very steep in places, take your time and enjoy the views. You will pass Crater Falls in a lovely rainforest before emerging at the mouth of the glacier-carved Crater Lake. The climbing continues up from here, with chains to assist one short rocky scramble up to Marion's Lookout and the amazing views over Dove Lake. Continue along the Overland Track to Kitchen Hut (a great lunch spot) where there is the potential side trip to Cradle Mountain. The Overland Track then continues 'behind' Cradle Mountain before wandering down the lovely Waterfall Valley. Before heading down to Waterfall valley is the option challenging side trip to Barn Bluff. One of the more challenging days on track with a stunning environment, start early and take your time to soak it all up. Let us begin by acknowledging the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we travel today, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. This is part of longer journey and can not be completed on it is own. Full journey: The Overland Track 1,330 1,238 1,146 1,054 962 870 0 m 6 km 7 km 540 m 5.9x 1.1 km 1.6 km 2.2 km 2.7 km 3.3 km 3.8 km 4.3 km 4.9 km 5.4 km 6.5 km 7.6 km 8.1 km 8.7 km 9.2 km 9.8 km 10.3 km 10.8 km Class 5 of 6 Rough unclear track Quality of track Formed track, with some branches and other obstacles (3/6) Gradient Very steep (4/6) Signage Clearly signposted (2/6) Infrastructure Limited facilities, not all cliffs are fenced (3/6) Experience Required Some bushwalking experience recommended (3/6) Weather Forecasted & unexpected severe weather likely to have an impact on your navigation and safety (5/6) Getting to the start: From Cradle Mountain Road, C132, Cradle Mountain. -

FMC Travel Club 25Th March to 16Th April 2017, 23 Days Ex Hobart $4495 Leader : Rob Brown a Comprehensive Tramping and Trave

FMC Travel Club A subsidiary of Federated Mountain Clubs of New Zealand (Inc.) www.fmc.org.nz Club Convenor : John Dobbs Travel Smart Napier Civic Court, Dickens Street, Napier 4110 P : 06 8352222 E : [email protected] 25th March to 16th April 2017, 23 days ex Hobart $4495 Leader : Rob Brown Based on 7 to 11 participants and subject to currency fluctuations Any payments by visa or mastercard adds $100 to the final price A comprehensive tramping and travel programme ex Hobart. Experience a tremendous range of landscapes across national parks, coasts and wilderness regions Encounter the wildlife, discover the convict past and enjoy Tassie’s relaxed style! This is a beaut little holiday….. PRICE INCLUDES : Accommodation – small characterful hotel, holiday park cabins, hostels, national park huts and tent camping Transport in a hired minibus with luggage trailer, other transfers as are needed to access tracks, etc Most meals as shown in the itinerary by B.L.D (the schedule is subject to revision) Experienced Kiwi trip leader throughout National Park entry fees, all Overland Track fees, entry to a wildlife park, return Hobart airport transfers and payment to FMC PRICE DOES NOT INCLUDE : Flights to / from Tasmania Some meals and personal incidentals Travel insurance Trip Leader : Rob Brown has been a leading NZ landscape photographer for 0ver 25 years. During this time he has been widely published in calendars, magazines and books and will be very familiar to most through these publications. He runs a small publishing and photography business in Wanaka and has also been involved in logistics and location work for the NZ TV and film industry where the same skills are used to bring people together to achieve a common goal. -

Windermere Site Concept Plan 2019

WINDERMERE SITE CONCEPT PLAN prepared for Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service Inspiring Place WINDERMERE SITE CONCEPT PLAN prepared for Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services Inspiring Place Pty Ltd Environmental Planning, Landscape Architecture, Tourism & Recreation 210 Collins St Hobart TAS 7000 T 03 6231 1818 E [email protected] ACN 58 684 792 133 30 May 2019 V1 for PWS review 01 June 2019 V2 for PWS review 19 June 2019 V3 for PWS review 12 August 2019 V4 for PWS review 21th August 2019 V5 for PWS review 26th August 2019 V6 for Public Consultation 12th November 2019 V7 for PWS review 25th November 2019 V8 (FINAL) for PWS 4 Windermere Site Concept Plan CONTENTS Section 1 Background ............................................................ 7 Section 2 Site Concept Plan ................................................ 12 2.1 Planning and Policy Context ............................................................ 12 2.2 The Site Concept Plan ...................................................................... 18 2.2.1 Windermere Hut ........................................................................... 19 2.2.2 Toilets ........................................................................................... 23 2.2.3 Ranger Hut ................................................................................... 24 2.2.4 Tent Platforms ............................................................................... 25 2.2.5 Rerouting the Track ...................................................................... 26 2.2.6 -

Trevor John Tolputt

FINDINGS and RECOMMENDATIONS of Coroner McTaggart following the holding of an inquest under the Coroners Act 1995 into the death of: Trevor John Tolputt 2 Contents Hearing Dates ......................................................................................................................... 3 Representation ...................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background ............................................................................................................................ 5 Circumstances Surrounding Mr Tolputt’s Death ................................................................... 6 Mr Tolputt’s Time of Death ................................................................................................. 12 The Reporting of Mr Tolputt as an Overdue Walker ........................................................... 14 Analysis of Issues Raised by this Inquest ............................................................................. 18 Findings Required by s28(1) of the Coroners Act 1995 ....................................................... 29 Recommendations ............................................................................................................... 30 3 Record of Investigation into Death (With Inquest) Coroners Act 1995 Coroners Rules 2006 Rule 11 I, Olivia McTaggart, Coroner, -

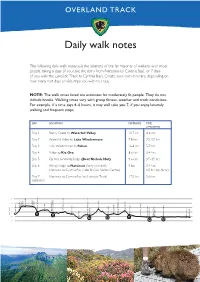

Daily Walk Notes

Height (metres) 1000 1200 1400 1600 600 800 Ronny Creek Crater Lake Marions Lookout Kitchen Hut how many rest days or side-trips you wish to enjoy. enjoy. wishto orside-tripsyou days rest many how dependingon itinerary, own your Create CynthiaBay). to Track walktheLakeside (if you or7days CynthiaBay), to Narcissus from theferry take (if you people taking 6 days withmost majorityofwalkers, suittheitinerary walknotes daily ofthefar The following walking andfrequent stops. leisurely enjoy ifyou you 7, take well 4–6hours,itmay example,For ifatimesays conditions. weather andtrack vary fitness, withgroup Walking times include breaks. NOTE: (optional) 7 Day 6 Day 5 Day 4 Day 3 Day 2 Day 1 Day DAY junction Waterfall Valley Hut The walk times listed are estimates for moderately fitpeople. donot moderately They for estimates are The walktimeslisted Lake Will Narcissus to Cynthia Bay (via Lakeside Track) (viaLakeside CynthiaBay to Narcissus Centre) StClairVisitor (Lake CynthiaBay to Narcissus Windy Ridgeto WindyRidge Kia Orato to Pelion to Windermere Lake to Valley Waterfall to Creek Ronny LOCATION Lake Windermere Windermere Hut Kia Ora Forth Valley Lookout Daily walk notes Daily OVERLAND TRACK OVERLAND Narcissus Waterfall Valley Waterfall Pelion Creek Lake Windermere Lake Pelion Frog Flats (Bert NicholsHut) (ferry terminal), terminal), (ferry Old Pelion Hut Junction Pelion Hut Pelion Gap Kia Ora Hut Du Cane Hut Hartnett Falls Junction Du Cane Gap 9.6 km 7.8 km 10.7 km 16.8 km 9 km 8.6 km 17.5 km DISTANCE Windy Ridge Pine Valley Junction 3.5-4.5 hrs 2.5-3.5 hrs 4-6 hrs 5-7 hrs 3-4 hrs 3-4 hrs 5-6 hrs 0.5 hrs(onferry) (APPROXIMATE) Narcissus River TIME Narcissus Hut Cuvier Valley Track Junction Echo Point Hut Watersmeet Cynthia Bay Day 1 Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley Distance: 10.7 km Time: 4-6 hours Terrain: Gradual ascent to Crater Lake, followed by a very steep, short ascent to Marions Lookout. -

2531 WHA Man Folder Cover

Tasmanian Wilderness Tasmanian World Heritage Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area MANAGEMENT PLAN 1999 Area Wilderness MANAGEMENT World Heritage PLAN 1999 Area “To identify, protect, conserve, present and, where appropriate, rehabilitate the world heritage and other natural and cultural values of the WHA, and to transmit that heritage to future generations in as good or better condition than at present.” WHA Management Plan, Overall Objective, 1999 MANAGEMENT PLAN PARKS PARKS and WILDLIFE and WILDLIFE SERVICE 1999 SERVICE ISBN 0 7246 2058 3 Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area PARKS MANAGEMENT PLAN and WILDLIFE 1999 SERVICE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN 1999 This management plan replaces the Tasmanian Abbreviations and General Terms Wilderness World Heritage Area Management The meanings of abbreviations and general terms Plan 1992, in accordance with Section 19(1) of the used throughout this plan are given below. National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970. A glossary of technical terms and phrases is The plan covers those parts of the Tasmanian provided on page 206. Wilderness World Heritage Area and 21 adjacent the Director areas (see table 2, page 15) reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970 and has been The term ‘Director’ refers to the Director of prepared in accordance with the requirements of National Parks and Wildlife, a statutory position Part IV of that Act. held by the Director of the Parks and Wildlife Service. The draft of this plan (Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan 1997 the Minister Draft) was available for public comment from 14 The ‘Minister’ refers to the Minister administering November 1997 until 16 January 1998. -

Alaskans in Tasmania Wildcare at Melaleuca Blind on Barn Bluff Gift

WILDTIMESEdition 40 April 2011 ALASKANS IN TASMANIA WILDCARE at MELALEUCA BLIND ON BARN BLUFF GIFT FUND PROJECT SUCCESSES, AND MUCH More … 2 – WILDTIMES – April 2011 Editorial Another summer season is behind us and more than ever this edition of Wildtimes is a celebration of the many fantatstic Wildcare projects taken place and individual volunteers’ stories I have come across since Christmas. I think you’ll especially enjoy reading about individual volunteer experiences from Steve Cronin, Helen Young and Alaskan visitors Clay Alderson and Claudia Rector. Ann Stephen’s and Gerry Delaney’s account of one harrowing afternoon on the Overland Track offers much food for thought, even perhaps debate. Before we put last summer behind us, make sure you look through those digital photos taken on Wildcare activities and send in your entries for this year’s photo competition. Our theme this time is ‘Wildcare Volunteers at Work and Play’, and the prize is $1,000 to the Wildcare branch nominated by Summer Sailing in Bass Strait, photo Steve Cronin see page 16 the winning photographer. Entries close 29 July 2011. More details inside this issue. If you’re one of Wildcare’s newer members wondering how to APOLOGY get more involved in our on-ground project see our piece on The Wildcare Board of Management apologises for ‘Better Pathways to Volunteering’. the late notice by mail for this year’s Annual General Personally, I’m revisiting a previous Parks career as a trackworker, Meeting, held at Mt Field National Park on with 3-4 months work on a great new project at Melaleuca. -

Tasmania Island Overland Track 縦走報告(前編)

Tasmania Island Overland Track 縦走報告(前編) M3 荒川 晶 ①Overland Track とは オーストラリアでの短期留学の後、メルボルン沖合にあるタス マニア島の Ovrland Track と呼ばれるトレッキングルートを 2/24(Mon)~3/2(Sun)の 7 日間掛けて縦走してきました。 Overland Track とは、島内中部にある Mt.Cradle National Park から Lake St.Clair National Park までのおよそ 70km に渡 るトレッキングルートです。先の Milford Track の場合と同様、 これらの国立公園は国が強い権限を持って管理しています。 このため、Peak Season である 10/01~翌 05/31 の間に個人で このトレッキングルートを歩く場合、 ①北から南への一方通行 ②入山者は 1 日 40 人以内 ③通行料として、国立公園への入園料$30 の他 に通行料$200 を支払うこと の 3 つの条件が課せられます。 先に「個人で」と書きましたが、この他にも ツアー会社がキャンプでのトレッキングツアー、 またこの公園内に許可を得て幾つか私設の山小 屋を持つ会社が、食事寝具等全て込のツアー(相 当高額になるが)を企画しています。今回の山行 中には前者は見かけませんでしたが、後者は 15 人ぐらいのグループが歩いているのを度々目に したので、おそらくそれに相当するのでしょう。 なお私設の山小屋は一般には開放されておらず、 また目につきにくい位置にあるので、5 つある 小屋のうち私は 2 つしか見つけることが出来ま せんでした。 個人で歩く場合は、コース途中に設けられて いる幾つかの小屋(以下 Hut と表記)に泊まるか、 その付近の Campsite でテントを張るかの何れ かになります。Hut の設備は日本の避難小屋相 当で、寝具食事調理器具は全て持参、水トイレ の設備あり、管理人が常駐(しているかと思って いたが、一部の小屋は駐在していないようだっ た)。収容人数は Hut 毎に大きく変わり、最低 16~最高 36 まで様々。また一旦縦走を開始すれば日程は 好きに組んで良い。その事や、もともと小屋の定員が少なく設定されているために、小屋に全員が宿泊 できないので、Hut 泊の予定でも必ずテントを持参するように HP 上で指示されています。 今回私が歩いていた間はやや閑散期だったようで、Walker の数はおよそ 1 日あたり 15 人。そのため 小屋も混雑することなく快適に過ごすことが出来ました。 ②概要・感想 Overland Track は Australia 国内でも相当有名のようで、留学先でも実習が終わったら Overland Track を歩く予定だと言ったら大体の人は That’s Great. Enjoy your walk! と言ってくれました。 また、この Overland Track はメインルートの他に、付近の山々に登ったり、湖を訪ねたり、渓谷にあ る滝を鑑賞する Side Trip が幾つも準備されています。1 日の行程は 4~5 時間程度と、日本の感覚から すれば、かなりゆとりを持って組まれているので、メジャーな Mt.Cradle、Mt.Ossa の 2 つのピークは 天候にさえ恵まれればほぼ全員が立ち寄ります。私は事前に色々調べて、このほか Barn Bluff、 Mt,Oakleigh、Mt.Acropolis の 3 つの山に登ることが出来ました。 この地域全体は安定陸塊に属しているため、浸食輪廻の壮年期に相当する日本の山々とは違い、概ね