The Politics of Pesticides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Full Version of Cv

Adrian David Cheok AM Phone: +61423977539 or +60128791271 19A Robe Terrace Email: [email protected] Medindie, 5081 Homepage: https://www.adriancheok.info Australia https://www.imagineeringinstitute.org Personal Date of Birth: December 18, 1971. Place of birth: Adelaide, Australia Australian Citizen. Summary of Career Adrian David Cheok AM is Director of the Imagineering Institute, Malaysia, Full Professor at i-University Tokyo, Visiting Professor at Raffles University, Malaysia, Visiting Professor at University of Novi Sad-Serbia, on Technical faculty \Mihailo Pupin", Serbia, Faculty of Ducere Business School, and CEO of Nikola Tesla Technologies Corporation. He is Founder and Director of the Mixed Reality Lab, Singapore. He was formerly Professor of Pervasive Computing, University of London, Full Professor and Executive Dean at Keio University, Graduate School of Media Design and Associate Professor in the National University of Singapore. He has previously worked in real-time systems, soft computing, and embedded computing in Mitsubishi Electric Research Labs, Japan. In 2019, The Governor General of Australia, Representative of Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II, has awarded Australia's highest honour the Order of Australia to Adrian David Cheok for his contribution to international education and research. He has been working on research covering mixed reality, human-computer interfaces, wearable computers and ubiquitous computing, fuzzy systems, embedded systems, power electronics. He has successfully obtained approximately $130 million dollars in funding for externally funded projects in the area of wearable computers and mixed reality from Daiwa Foundation, Khazanah National (Malaysian Government), Media Development Authority, Nike, National Oilwell Varco, Defence Science Technology Agency, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Communications and Arts, National Arts Council, Singapore Sci- ence Center, and Hougang Primary School. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Organizing for Social Justice: Rank-and-File Teachers' Activism and Social Unionism in California, 1948-1978 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6b92b944 Author Smith, Sara R. Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ORGANIZING FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE: RANK-AND-FILE TEACHERS’ ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL UNIONISM IN CALIFORNIA, 1948-1978 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY with an emphasis in FEMINIST STUDIES by Sara R. Smith June 2014 The Dissertation of Sara R. Smith is approved: ______________________ Professor Dana Frank, Chair ______________________ Professor Barbara Epstein ______________________ Professor Deborah Gould ______________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Sara R. Smith 2014 Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 57 The Red School Teacher: Anti-Communism in the AFT and the Blacklistling of Teachers in Los Angeles, 1946-1960 Chapter 2: 151 “On Strike, Shut it Down!”: Faculty and the Black and Third World Student Strike at San Francisco State College, 1968-1969 Chapter 3: 260 Bringing Feminism into the Union: Feminism in the California Federation of Teachers in the 1970s Chapter 4: 363 “Gay Teachers Fight Back!”: Rank-and-File Gay and Lesbian Teachers’ Organizing against the Briggs Initiative, 1977-1978 Conclusion 453 Bibliography 463 iii Abstract Organizing for Social Justice: Rank-and-File Teachers’ Activism and Social Unionism in California, 1948-1978 Sara R. -

TION HONORABLE WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR. United States Senator

) BIOGRAPHICAL INFO~~TION HONORABLE WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR. United States Senator Delaware William Roth was elected to the United States Senate as a Republican from Delaware in 1970 and served as a member of the House of Representatives from 1966-1970. From 1961-1964 he was Chairman of the Delaware Republican State Committee and a member of the Republican National Committee. Senator Roth holds a B.A. degree from the University of Oregon, an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School, and an LL.B. from Harvard Law School. He serves on two key Senate Committees, Finance and Gov ernmental Affairs. His Finance Committee responsibilities in volve him in many issues of concern to international business, including tax, energy and trade policy. Senator Roth is a member of the Finance Subcommittee on International Trade, and he has been very active in consideration of the Administration's energy program, leading opposition to the crude oil equalization tax and/or increased import duties on imported oil. Senator Roth is also the second ranking Senate Republican on the Joint Economic Committee. • • • FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JANUARY 26, 1967 Office of the White House Press Secretary -- --- -- ---------- ---- -- ---- --- --- - - --. - ---- THE WHITE HOUSE President Johnson today announced his intention to nominate Ambassador W"illi<l:!!! .. M.• Roth~of California, to be Special Representative for Trade Negotiations. Ambassador Roth, since 1963, has served as Deputy Special Representative for Trade Negotiations. If confirmed by the Senate, Ambassador Roth would fill the vacancy created by the recent death of Governor Christian Herter. Ambassador Roth was born September 3, 1916 in San Francisco, California. -

Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Cleveland Memory Books Summer 7-2013 Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks Part of the United States History Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Klein, Richard, "Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times" (2013). Cleveland Memory. 18. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland Memory by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein, Ph.D Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein, Ph.D An online accessible format of this book can be found at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks/18/ The digital version is brought to you for free and open access at EngagedScholarship@CSU. 2013 MSL Academic Endeavors Imprint of Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University Published by MSL Academic Endeavors Cleveland State University Michael Schwartz Library 2121 Euclid Avenue Rhodes Tower, Room 501 Cleveland, Ohio 44115 http://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/ ISBN: 978-1-936323-02-9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License CLEVELAND MAYOR RALPH J. PERK STRONG LEADERSHIP DURING TROUBLED TIMES TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 3 Acknowledgments 4 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Pressing New Urban Challenges 8 Chapter 2: The Life and Times of Ralph J. -

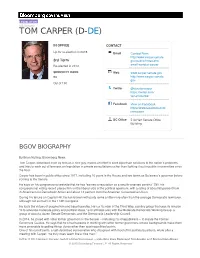

Tom Carper (D-De)

LEGISLATOR US Senator TOM CARPER (D-DE) IN OFFICE CONTACT Up for re-election in 2018 Email Contact Form http://www.carper.senate. 3rd Term gov/public/index.cfm/ Re-elected in 2012 email-senator-carper SENIORITY RANK Web www.carper.senate.gov 24 http://www.carper.senate. gov Out of 100 Twitter @senatorcarper https://twitter.com/ senatorcarper Facebook View on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ tomcarper DC Office 513 Hart Senate Office Building BGOV BIOGRAPHY By Brian Nutting, Bloomberg News Tom Carper, described even by foes as a nice guy, makes an effort to seek bipartisan solutions to the nation’s problems and tries to work out differences on legislation in private consultations rather than fighting it out in public in committee or on the floor. Carper has been in public office since 1977, including 10 years in the House and two terms as Delaware’s governor before coming to the Senate. He says on his congressional website that he has “earned a reputation as a results-oriented centrist.” Still, his congressional voting record places him on the liberal side of the political spectrum, with a rating of about 90 percent from th Americans for Democratic Action and about 10 percent from the American Conservative Union. During his tenure on Capitol Hill, he has broken with party ranks a little more often than the average Democratic lawmaker, although not so much in the 113th Congress. He touts the virtues of pragmatism and bipartisanship. He’s a founder of the Third Way, a policy group that says its mission “is to advance moderate policy and political ideas,” and affiliates also with the Moderate Democrats Working Group, a group of about a dozen Senate Democrats, and the Democratic Leadership Council. -

GERMANY ACCEPTS ARMISTICE TERMS and ALL HOSTILITIES ARE CONCLUDED; CONDITIONS ANNOUNCED by PRESIDENT President Announces Signing of Armistice

THE WAR THUS CQMES TO AN END-Woodrow Wilson PUBLLFHED DAZLY under order of THE PREXIDENT of THE UNZTED STATES by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC ZNFORMATZON GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * COMPLETE Record of U. .. GOVERNMENT .Activities VOL. 2 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 1918. No. 460 GERMANY ACCEPTS ARMISTICE TERMS AND ALL HOSTILITIES ARE CONCLUDED; CONDITIONS ANNOUNCED BY PRESIDENT President Announces Signing of Armistice. My fellow countrymen: The armistice was signed this morning. Everything for which America fought has been accomplished. It will- now be our fortunate duty to assist by example, by sober, friendly counsel, and by mnaterial aid in the establishment of just democracy throughout the world. WOODROW WILSON. The Secretary of State an- armistic, between the Allies November 11, 1918, and that nounces the receipt of advices and the United States and Ger- hostilities would cease at 11 from.Paris which state Jha the many was signed at 5 a. In., a. m. to-day. DRAFT CALLS SUSPENDED, GERMANY TO GIVE UP ALSACE-LORRAINE, SECRETARY OF WAR ANNOUNCES DEMOBILIZE ARMIES, MAKE REPARATION, Men Now Entrained for Camps UNDER TERMS OF THE AGREEMENT SIGNED Also to be Turned Back as Far as Possible. stupendous change it will in some President Tells Con- degree lighten my sense of respon- gress of Armistice sibility to perform in person the At 10.50 o'clock this morning the See- duty of communicating to you some retary of \Yar made the following an- Terms of the larger circumstances of the nouncement: situation with I have suspended further calls under which it is necessary At a joint session of the two to deal. -

Future (Spokane, Waslangton, October'25-27, 1974); INSTITUTION Wa Ingtoncstli., Seattle: Inst

DOCUMENT-RESUME ED 124 394 SE 019 64.4 AUTHOR Widditsch, Ann, Ed.. TITLE Procl.ldings of .Learning for Survival:, A Symposium on Environmental EdUcation and Water Quality for the Future (Spokane, Waslangton, October'25-27, 1974); INSTITUTION Wa ingtoncstli., Seattle: Inst. for Environmental S dies. ':--:,*.' = . SPONS AGENCY Finvironmental,Protection Agency, 'Washington, D.C. Office of Water Programs. ; . PUB DATE Oct 74 -, , NOTE 466p.; Some small. print AVAILABLE _FROM Tnstitute for Egvironmental StUdies,University of Washington, Sea'tle, Washington 981`95 (free) EDRS PRICE MF-SC.83HC-$24.77 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conference R.sports; Conferences; Element ry Education; *Environment; *Environmental E ationy; HigheEducation; International Education; Re earch; Secon ary Education; Teacher Education; *Water Pont io:1 Control IDENTIFIERS *EXPO 74 ABSTRACT This book contains a reco d of papers and edited transcripts presented at a program sponsa ed by the Institutefor Environm,?ntal Studies: The program was,,part of, an International' Exposition on the EnvironMent, EXPO 74 held in Spokane, Washington. The program,ncorporated three areas of interest: deSigning and finding methods for improving environmental education at all levels of learning including professional educators, civil servants,elected officials, industrial representatives, students, and citizens; special sessions on water quality education for members of the Environmental Protection Agency Advisory Committee; and special sessions on the management of large-scale interdisciplinary reseafth projects for educators involved in a National Science Foundation grant. The general sessions included speeches onuniversity and ecnraary prograMs, international programs!, political views,and financin,g. The special sessions covered topics'in water quality education, curriculum, research, and publicservice. (Editor/MR) * Documents acqUired by ERIC include ma.y informal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. -

Sr001-Xxx.Ps

1 107th Congress "!S. RPT. 1st Session SENATE 107–1 ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE AND ITS SUBCOMMITTEES FOR THE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS JANUARY 29, 2001.—Ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2001 VerDate 29-JAN-2001 04:09 Jan 30, 2001 Jkt 089010 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 E:\HR\OC\SR001.XXX pfrm02 PsN: SR001 congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine CARL LEVIN, Michigan GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire MAX CLELAND, Georgia ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JEAN CARNAHAN, Missouri HANNAH S. SISTARE, Staff Director and Counsel ELLEN B. BROWN, Senior Counsel JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Democratic Staff Director and Counsel DARLA D. CASSELL, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate 29-JAN-2001 04:09 Jan 30, 2001 Jkt 089010 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 7633 Sfmt 6646 E:\HR\OC\SR001.XXX pfrm02 PsN: SR001 III 105TH CONGRESS FRED THOMPSON, TENNESSEE, Chairman WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., DELAWARE 1 JOHN GLENN, Ohio TED STEVENS, Alaska 1 CARL LEVIN, Michigan SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey DON NICKLES, Oklahoma MAX CLELAND, Georgia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania BOB SMITH, New Hampshire 2 ROBERT F. -

293 Hon. Ginny Brown-Waite

January 7, 2009 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 155, Pt. 1 293 [From the St. Petersburg Times, Jan. 3, 2009] Mr. Moore was known in Pinellas and Hinesley, Moore was persuaded by a former BOISTEROUS AND FITTING FAREWELL across the state for his knowledge of Flor- PCTA president to lobby School Board mem- (By Thomas C. Tobin and Donna Winchester) ida’s budget and politics. He took tough bers for the four votes necessary to remove stances, including pushing for a teacher raise Hinesley. He failed, and to the day he passed CLEARWATER.—He loved roses and Broad- way musicals. He stunk at golf, though he this year even as the district plunged into a away he seemed to regret what he had done. had a whale of a time playing it. deep economic hole. But he maintained a Guerrilla politics were never Moore’s style, He was an optimist, active in his church, collaborative style and an optimistic out- and the failed attempt nearly severed his re- strong in his views. He was a reader and a look. lationship with Hinesley. ‘‘I’ll never go there smiler, a pundit, a partier, a people lover. ‘‘All of us knew that Jade meant what he again,’’ he would say. ‘‘I won’t do it.’’ And when it came to teachers, Jade Thom- said, that ... his views were in support of the The lesson was never lost, and Moore even as Moore—the executive director of the many, not of the few, and that he would al- found himself taking friendly fire as a result. -

No Shortcuts: the Case for Organizing

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 No Shortcuts: The Case for Organizing Jane Frances McAlevey Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1043 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] i No Shortcuts: The Case for Organizing by Jane F. McAlevey A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii COPYRIGHT © 2015 JANE F. MCALEVEY All Rights Reserved iii APPROVAL PAGE, NO SHORTCUTS: THE CASE FOR ORGANIZING This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology to satisfy the dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Approved by: Date Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ _________________________________________ Frances Fox Piven, Professor Date Executive Officer, Sociology ______________________ __________________________________________ Philip Kasinitz, Professor Supervisory Committee Members James Jasper, Professor William Kornblum, Professor Dan Clawson, Professor, UMASS Amherst THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Abstract No Shortcuts: The Case for Organizing By Jane McAlevey Advisor: Frances Fox Piven This dissertation will explore how ordinary workers in the new economy create and sustain power from below. In workplace and community movements, individuals acting collectively have been shown to win victories using a variety of different approaches. -

Secrets of a Successful Organizer

SECRETS OF A SUCCESSFUL ORGANIZER TRAINER’S GUIDE Adapted for the National Education Association Center for Organizing CHRIS BROOKS, SONIA SINGH, AND SAMANTHA WINSLOW LABOR NOTES l labornotes.org SECRETS OF A SUCCESSFUL ORGANIZER TRAINER’S GUIDE Adapted for the NEA Center For Organizing, June 2018 INTRODUCTION Trainer’s Guide Organizing at NEA The NEA—in response to the relentless threats to public education, public employees, students, and communities—is partnering with state and local affiliates to build an Association-wide culture of organizing. Our goal is to build on our legacy of advocacy and leading the professions, fight for our mission of great public schools for all students, and grow sustainable, strong NEA affiliates for the future. A culture of organizing is one that promotes deep member engagement, leadership development, and collective action. At its core, organizing means facilitating collective action among a group and empowering others to take on leadership roles. A culture of organizing is an intentional and strategic approach to the work of the Association: one that relies on data analytics, thoughtful planning, accountability, and continuous improvement. The NEA Center for Organizing measures successful organizing through multiple lenses: robust member engagement, effective distributive leadership structures, and growth in membership. We seek to build these capacities through organizing campaigns built around the issues important to our members. Many different organizing strategies can lead to success; nonetheless, all authentic organizing is accountable for measurable goals and outcomes. Above all, we believe in leading with vision and aspiration, accompanied by concrete programs and plans. Effective organizing—which is what we all strive for—should result in increased member engagement of significant numbers of educators, expanding leadership, and real wins in the policies and practices that impact our members, our schools, our students and our communities—grounded in our values of equity, opportunity, and racial justice.