Forming Identities at Dr Graham's Homes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KALIMPONG, PIN - 734301 E-Mail: [email protected] TEL : 03552-256353, 255009

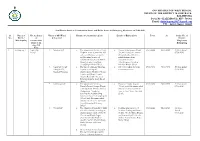

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE, KALIMPONG PO & PS - KALIMPONG, PIN - 734301 E-mail: [email protected] TEL : 03552-256353, 255009 At a Glance details of Containment Zones and Buffer Zones in Kalimpong District as on 19.06.2020 Sl. Name of No. & details Name of GP/Ward Details of Containment Zone Details of Buffer Zone From To Order No. of No. Block / of & Location District Municipality containment Magistrate Zone as on Kalimpong date, GP Wise 1. Kalimpong-I Eight (08) 1. Samthar G.P a. The Quarantine Centre of Lalit a. House of Gangaram Bhujel 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated Zones Pradhan at the community hall (North) House of Laxman 07.06.2020 of Lower Dong covering the Bhujel (South) 100 metre neighbouring houses of radial distance from Krishna Bhujel (North) Bimal containment zone Bhujel (South), Landslide (East)House of Krishna (East)Sukpal Bhujel (West) Bahadur Bhujel (West) 2. Yangmakum GP a. The House of Dong Tshering a. 100 metre radius from the 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated (Dinglali GP, Lepcha covering the containment zone 07.06.2020 Kambal Fyangtar) neighbouring Houses of Josing Lepcha and Birmit Lepcha (South) Road (North), Som Tshering Lepcha (East) Road (West) 3. Nimbong G.P a. The Quarantine centre of a. House of Timbu Lepcha 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated Kamala Rai and Anupa Bhujel (North) and 100 metres radial 07.06.2020 at Dalapchand Primary School, distance from containment Dalapchand, Nimbong, zone in East, West, North & covering the neighbouring South. -

Village & Town Directory ,Darjiling , Part XIII-A, Series-23, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERmS 23 'WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIll-A VILLAGE & TO"WN DIRECTORY DARJILING DISTRICT S.N. GHOSH o-f the Indian Administrative Service._ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL · Price: (Inland) Rs. 15.00 Paise: (Foreign) £ 1.75 or 5 $ 40 Cents. PuBLISHED BY THB CONTROLLER. GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY MILl ART PRESS, 36. IMDAD ALI LANE, CALCUTTA-700 016 1988 CONTENTS Page Foreword V Preface vn Acknowledgement IX Important Statistics Xl Analytical Note 1-27 (i) Census ,Concepts: Rural and urban areas, Census House/Household, Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal Workers, N on-Workers (ii) Brief history of the District Census Handbook (iii) Scope of Village Directory and Town Directory (iv) Brief history of the District (v) Physical Aspects (vi) Major Characteristics (vii) Place of Religious, Historical or Archaeological importance in the villages and place of Tourist interest (viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory data. SECTION I-VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1. Sukhiapokri Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 31 (b) Village Directory Statement 32 2. Pulbazar Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 37 (b) Village Directory Statement 38 3. Darjiling Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 43 (b) Village Directory Statement 44 4. Rangli Rangliot Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 49- (b) Village Directory Statement 50. 5. Jore Bungalow Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 57 (b), Village Directory Statement 58. 6. Kalimpong Poliee Station (a) Alphabetical list of viI1ages 62 (b)' Village Directory Statement 64 7. Garubatban Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 77 (b) Village Directory Statement 78 [ IV ] Page 8. -

Best of Gangtok Kalimpong Darjeeling Rs 20,199

anytymfly Contact No : +91 6364460897 +91 6364460893 +91 6364460892 080 43940049 Best Of Gangtok TOTAL PRICE Rs 20,199 Kalimpong Darjeeling Tours Name: Best Of Gangtok Kalimpong Darjeeling Total Price : Rs 20,199 Duration Start City End City Places covered 5 Days / 4 Nights Gangtok Darjeeling Gangtok,Darjeeling,Kalimpong, Bagdogra overview Darjeeling is a popular hill station in North-East India. It is surrounded by huge mountains. The flow of tourists in Darjeeling is increasing day by day. Darjeeling is world famous for its Tea and its aroma. All tea drinkers love having Darjeeling tea and don’t forget to get Darjeeling tea, when they visit there. Darjeeling is full of nature’s beauty, lofty mountains, and waterfalls and off course one cannot forget to see the Kanchenjunga Peak. ADVENTURE | FAMILY | EDUCATIONAL Introduction Explore the north eastern attractions this holiday. Take a week’s off and hike up to the charms of Kalimpong, Darjeeling and Gangtok. While Kalimpong is tucked in the peaceful environs near Darjeeling offering absolute freshness, Itinerary Details Day 1 Visiting Place: Description: IXB AIRPORT & GANGTOK 1 / 4 anytymfly Arrive at NJP Railway Station / IXB Airport & transfer to Gangtok (5,480 ft.), the capital of Sikkim. Check-in to hotel & rest of the day is free at leisure. Shop around at M.G. Marg & explore the city on your own. Spend overnight at hotel in Gangtok. (Please Submit One Photo copy of photo-id proof and 02 Passport size photo at Hotel Reception if Next day is Tsongmo Lake Sightseeing). Day 2 Visiting Place: Description: GANGTOK & TSOMGO LAKE & BABA MANDIR After a sumptuous breakfast visit Tsomgo Lake (12,400 ft.) & Baba Mandir (13,200 ft.) which is 55 kms one way from Gangtok city. -

The Study Area

THE STUDY AREA 2.1 GENERALFEATURES 2.1.1 Location and besic informations ofthe area Darjeeling is a hilly district situated at the northernmost end of the Indian state of West Bengal. It has a hammer or an inverted wedge shaped appearance. Its location in the globe may be detected between latitudes of 26° 27'05" Nand 27° 13 ' 10" Nand longitudes of87° 59' 30" and 88° 53' E (Fig. 2. 1). The southern-most point is located near Bidhan Nagar village ofPhansidewa block the nmthernmost point at trijunction near Phalut; like wise the widest west-east dimension of the di strict lies between Sabarkum 2 near Sandakphu and Todey village along river Jaldhaka. It comprises an area of3, 149 km . Table 2.1. Some basic data for the district of Darjeeling (Source: Administrative Report ofDatjeeling District, 201 1- 12, http://darjeeling.gov.in) Area 3,149 kmL Area of H ill portion 2417.3 knr' T erai (Plains) Portion 731.7 km_L Sub Divisoins 4 [Datjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Si1iguri] Blocks 12 [Datjeeling-Pulbazar, Rangli-Rangliot, Jorebunglow-Sukiapokhari, Kalimpong - I, Kalimpong - II, Gorubathan, Kurseong, Mirik, Matigara, Naxalbari, Kharibari & Phansidewa] Police Stations 16 [Sadar, Jorebunglow, Pulbazar, Sukiapokhari, Lodhama, Rangli- Rangliot, Mirik, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Gorubathan, Siliguri, Matigara, Bagdogra, Naxalbari, Phansidewa & Kharibari] N o . ofVillages & Corporation - 01 (Siliguri) Towns Municipalities - 04 (Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Mirik) Gram Pancbayats - 134 Total Forest Cover 1,204 kmL (38.23 %) [Source: Sta te of Forest -

Nepali’ Women of Darjeeling

INDIA’S NATIONALIST MOVEMENT AND THE PARTICIPATION OF ‘NEPALI’ WOMEN OF DARJEELING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE By KALYANI PAKHRIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. RANJITA CHAKRABORTY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL DARJEELING, INDIA-734013 MARCH, 2017 Dedicated to my parents D E C L A R A T I O N I declare that the thesis entitled “India’s Nationalist Movement and the participation of ‘Nepali’ women of Darjeeling” has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. Ranjita Chakraborty, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. KALYANI PAKHRIN Department of Political Science University of North Bengal Darjeeling: 734013, West Bengal, India. Date:07/03/2017 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur Dr. Ranjita Chakraborty P.O. North Bengal University Department of Political Science ENLIGHTENMENT TO PERFECTION Dist. Darjeeling, 734013 West Bengal (India) Ref. No……………………………. Date: …………………….……… C E R T I F I C A T E I certify that Miss Kalyani Pakhrin has prepared the thesis entitled “India’s Nationalist Movement and the participation of ‘Nepali’ women of Darjeeling” for the award of Ph.D. degree of the University of North Bengal, under my guidance. I also certify that she has incorporated in her thesis the recommendations made by the Departmental Committee during her pre-submission seminar. She has carried out the work at the Department of Political Science, University of North Bengal. -

Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 1 Office of the ERO, 22-Kalimpong A.C

Name of the Nodal District AC No. AC Name Location of the VFCs personnel of the VFC Sangay Tamang / Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 1 Office of the ERO, 22-Kalimpong A.C. Nanglemit Lepcha Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 2 BDO'Office, Kalimpong-II, Algarah Veronica Gurung Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 3 Lingseykha GP Office Rohit Chettri Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 4 Lingsey GP Office Umesh Pariyar Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 5 Kagay GP Office Prakash Chettri Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 6 Pedong GP Office Phup Tsh. Bhutia Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 7 Sakyong GP Office Raj Kumar Sharma Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 8 Kashyong GP Office Umesh Rai Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 9 Santook GP Office Ravi Mangrati Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 10 Paiyong GP Office Maheshwar Sharma Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 11 Dalapchand GP Office Kharga Bikram Subba Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 12 Sangsay GP Office Binod Gajmer Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 13 Lolay GP Office Gopichand Sharma Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 14 Lava Gitbeong GP Office Tarkeshwar Kanwar Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 15 Gitdabling GP Office Robert Rai Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 16 Block Development Office Kalimpong-I Phurba Tamang Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 17 Bhalukhop GP Office Ranbir Tamang Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 18 Bong GP Office Bijay Kiran Lama Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 19 Kalimpong GP Office Deepak Kharga Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 20 Tashiding GP Offfice Smt. Tshering Y. Bhutia Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 21 Teesta GP Office Arpan Mukhia Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 22 Dungra GP Office Gajendra Kr. Chettri Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 23 Homes GP Office Dhan Kr. Chettri Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 24 Upper Echhey GP Office Sulav Pradhan Kalimpong 22 Kalimpong 25 Lower Echhey GP Office Indra Kr. -

49 Gurupada Haldar Road, Raj Apartment, Ground Floor, Kalighat, Kolkata – 700026, West Bengal, India [email protected]

49 Gurupada Haldar Road, Raj Apartment, Ground Floor, Kalighat, Kolkata – 700026, West Bengal, India [email protected] www.globaldiaries.in GD/SK – 30 13 Nights / 14 Days Gangtok 4N – Lachen 1N – Lachung 2N – Pelling 2N – Darjeeling 3N – Kalimpong 1N 1st Day: New Jalpaiguri Railway Station (NJP) / Bagdogra Airport (IXB) – Gangtok Distance: 120 kms (approx) Journey Time: 5 hrs (approx) Overnight stay at Gangtok. 2nd Day: Excurtion to Tsomgo Lake & New Baba Mandir (Permit Required) • Tsomgo Lake (12,400 ft.): It is a glacial lake in the East Sikkim district of the Indian state of Sikkim, some 40 kms from the capital Gangtok. • New Baba Mandir (13,200 ft.): Indian Army has built-in honour of Capt. Harbhajan Singh. Capt Singh is remembered as the "Hero of Nathula" by soldiers of the Indian army. Note: In case of closure of route and authority not issued permit to Tsomgo Lake than we will provide alternate sightseeing. Overnight stay at Gangtok. 3rd Day: Gangtok – Lachen (Permit Required) Distance: 105 kms (approx) Journey Time: 6 hrs (approx) Enroute Sightseeing: • Naga Waterfall: One of the longest and the scenic waterfalls with clean and ice-cold water. It is a multi-tiered waterfall. • The Confluence of Lachen & Lachung Chu (River) at Chungthang: It is a wonderful confluence as we see two river meeting in 2 different colours. • Bhim Nala Waterfall: It is a dazzling waterfall arranged at Khedum town close Lachung in North Sikkim. Bhim Nala Falls is one of the tallest waterfalls in Sikkim and among the prominent spots to visit in Lachung. Situated on Chungthang - Lachung street Overnight stay at Lachen. -

BEST of NORTH EAST Darjeeling – Gangtok – Kalimpong 7 Days / 6 Nights

P a g e | 1 364 Embassy, Koramangala, Bangalore. Ph: +91 9483958408, 9880388991, [email protected], www.takeabreak.in BEST OF NORTH EAST Darjeeling – Gangtok – Kalimpong 7 Days / 6 Nights GANGTOK KALIMPONG DARJEELING P a g e | 2 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS Darjeeling: Tiger hill sun rise, Himalayan mountaineering institute & zoo, cable car, Ghoom Monastery, Japanese temple, Observatory hill & Shopping Gangtok : Rumtek Monastery, Ranka Monastery, Ban Jakri Falls, Do-Dul Chorten, Institute of Tibetology, Hanuman Tok, Enchey Monastery, Tashi view point & Shopping Kalimpong: Thongsa Gompa, Durpin Dara hill & Jang Dong Palriffo Brang (Monastery) DAY 1: DARJEELING Darjeeling You will be greeted by the most exotic views that nature ever bestowed on mankind. Darjeeling, perhaps the most popular hill station in India, is located in West Bengal and is bedecked with many monuments of colonial heritage. Known as the Queen among all the hill stations, the hill station sits perched up on Mt. Kanchenjunga. Look around and you will see tea gardens and variety of flora and fauna scattered around everywhere. The town has not much to offer but unlimited natural attractions. Challenging treks and white water rafting lure every adventurer to Darjeeling. Day Notes Arrive Bagdogra Airport You will be greeted by our chauffeur and drive to hotel Check-in to the hotel & rest of the day at leisure Overnight at, Darjeeling Included BB DAY 2: DARJEELING Day Notes Early morning at 05:00 AM proceed to view sunrise over Kanchenjunga from Tiger Hills Visit Ghoom Monastery and Batasia Loop Return to the resort for breakfast Post breakfast proceed for sightseeing of Darjeeling Sightseeing of Darjeling: Himalayan mountaineering institute & zoo, Cable Car, Japanese temple & Observatory hill. -

Journey Quests

Journey Quests Northeast Honeymoon Package 7 Nights / 8 Days Darjeeling ‐ Kalimpong – Gangtok Day 1: Arrival in Siliguri ‐Transfer to Darjeeling‐ Arrive in Siliguri at New Jalpaiguri Railway Station (68 km) / Bagdogra Airport (69 km) / Tenzing Norgay Bus Stand (62 km), met our tour representative. He would help you in taking an assisted transfer to Darjeeling. Home to the World Heritage Train‐ the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (DHR) or the toy train, Darjeeling is an enchanting hill station. Lying at a height of 7100 feet above the sea level, Darjeeling has aromatic lush tea estates, tranquility in abundance, breathtaking scenery, Buddhist monasteries, bustling streets and several striking views. After you arrive in Darjeeling, check‐ into the hotel. You can relax for a while. The evening is at leisure and you can spend it as per your own liking. Have a leisure walk up to the Mall or visit the local shopping centers to get your hands on some memorabilia. Over Night stay at Darjeeling Day 2: Darjeeling sightseeing‐ Day 2 starts quite early. Get‐up around 3:45 AM to drive towards Tiger Hill (11 km) to view sunrise over the Kanchendzonga Peak (subject to clear weather). One of the major attractions in Darjeeling, the route taking to you the hill, amid Oak forests, is an extremely refreshing one. It is advisable to start early top save yourself from traffic snarls up the hill. When the sun rises behind from the hill, it illuminates the Peak and looks like an orange‐colored ball. Treat your eyes to the scenery and soak‐ in the tranquility. -

Disaster Management Plan Office of the District Magistrate Kalimpong 2017

1 Disaster Management Plan Office of the District Magistrate Kalimpong 2017 2 FOREWORD This hand book on District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) of Kalimpong Disaster Management section for information, guidance and management in the event of any disaster for the year, 2017 has been prepared. It contains the core concept of Disaster Management comprising preparedness, prevention, early warning system, Disaster Impact, quick response, mitigation, recovery and relief. The booklet comprises a discussion on the Hazard ,Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk Assessment, Institutional Arrangement for Disaster Management, Prevention and Mitigation Measures, Preparedness Measures, Capacity Building and Training Measures, Response and Relief Measures, Reconstruction, Rehabilitation and Recovery Measures, Financial Resources for implementation of DDMP, Procedure and Methodology for Monitoring, Evaluation, Updating and Maintenance of DDMP, Coordination Mechanism for Implementation of DDMP and Standard Operating Procedure and Check list, etc. including vulnerability assessment of the weak areas, of the District. The shelter point of the Kalimpong Municipality area and three blocks have been provided. The past history of the land slide under this District has been highlighted. The basic reasons of land slide in hill areas also have been added in this booklet. The action plans of the respective block and other line departments have been included in this booklet too. I extend my sincere thanks to Shri Nirmalaya Gharami W.B.C.S (Exe) Sub Divisional Officer, Kalimpong Sadar and Shri Abul Ala Mabud Ansar W.B.C.S(Exe) O/C DM Section and Dr. R.P. Sharma Engineer of this Office who has prepared all technical portion of the booklet, along with the officer and staff of the Disaster Management Section of this office, without whose help these booklet would not have been completed in due time. -

WEST BENGAL Retreats Offer Bhutan, Nepalandtibet

© Lonely Planet Publications 516 West Bengal Emerging from the tempestuous Bay of Bengal in a maze of primeval mangroves, West Bengal stretches across the vast Ganges plain before abruptly rising towards the mighty ramparts of the Himalaya. This long, narrow state is India’s most densely populated and straddles a breadth of society and geography unmatched in the country. As the cradle of the Indian Renaissance and national freedom movement, erstwhile Bengal has long been considered the country’s cultural heartland, famous for its eminent writers, poets, artists, spiritualists and revolutionaries. Overshadowed perhaps by the reputation of its capital Kolkata (Calcutta), it is nonetheless surprising that this rich and diverse state receives so few foreign tourists. In the World Heritage–listed Sunderbans, the Ganges delta hosts not only the world’s most extensive mangrove forest, but also the greatest population of the elusive Royal Bengal tiger. On the Ganges plains a calm ocean of green paddies surrounds bustling trading towns, mud-and-thatch villages, and vestiges of Bengal’s glorious and remarkable past: ornate, ter- racotta-tiled Hindu temples and monumental ruins of the Muslim nawabs (ruling princes). As the ground starts to rise, the famous Darjeeling Himalayan Railway begins its ascent to the cooler climes of former British hill stations. The train switches back and loops its way to Darjeeling, still a summer retreat and a quintessential remnant of the Raj. Here, amid Himalayan giants and renowned tea estates, lies a network of mountain trails. Along with the quiet, orchid-growing haven of nearby Kalimpong, once part of Bhutan, these mountain retreats offer a glimpse into the Himalayan cultures of Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal and Tibet. -

Spring Flowers of Sikkim, Darjeeling & Kalimpong

India – Spring Flowers of Sikkim, Darjeeling & Kalimpong Naturetrek Tour Report 24 May – 8 June 2015 Aristolochia griffithii Coelogyne ochracea Rhododendron cinnabarinum Primula calderiana Report & images compiled by Jenny Willsher Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk India – Spring Flowers of Sikkim, Darjeeling & Kalimpong Tour Report Tour Participants: Alister Adhikari Tour Leader Dipesh Tamang Assistant Jenny Willsher Naturetrek Naturalist Together with Naturetrek clients Summary Starting in the bustling atmospheric hill town of Darjeeling, our two weeks in the smallest of Indian states proved a fascinating mix of culture, tradition and natural history. Our travels in the mountainous North Sikkim, where the rainfall is naturally high, gave us dramatic waterfalls, luxuriant forests and other plant-rich areas but also the attendant complications of landslides and difficult road conditions. Botanical highlights included the beautiful Mecanopsis, both blue and yellow, the forest of Rhododendrons at Yumthang, the contrasting habitats of lush forest of towering Himalayan Alder, Teak, Albizia chinensis and Schima wallichii – some so draped in epiphytes as to make their own plant communities, the clouded high meadows strewn with Primulas, and the dramatic flowers of the various Arisaemas and the banks of ferns and grasses. Birdlife was always present, whether it was the noisy common birds such as Common Mynah, House Crow, various Drongos, Blue Whistling Thrush, fleeting glimpses of bright forest birds such as Scarlet Minivet or, in the high valleys, brief glimpses of Golden and Black Eagle, black and white Snow Pigeons and the bright blue Grandala.