On Logical Form* Danny Fox, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and Pragmatics Christopher Gauker Semantics deals with the literal meaning of sentences. Pragmatics deals with what speakers mean by their utterances of sentences over and above what those sentences literally mean. However, it is not always clear where to draw the line. Natural languages contain many expressions that may be thought of both as contributing to literal meaning and as devices by which speakers signal what they mean. After characterizing the aims of semantics and pragmatics, this chapter will set out the issues concerning such devices and will propose a way of dividing the labor between semantics and pragmatics. Disagreements about the purview of semantics and pragmatics often concern expressions of which we may say that their interpretation somehow depends on the context in which they are used. Thus: • The interpretation of a sentence containing a demonstrative, as in “This is nice”, depends on a contextually-determined reference of the demonstrative. • The interpretation of a quantified sentence, such as “Everyone is present”, depends on a contextually-determined domain of discourse. • The interpretation of a sentence containing a gradable adjective, as in “Dumbo is small”, depends on a contextually-determined standard (Kennedy 2007). • The interpretation of a sentence containing an incomplete predicate, as in “Tipper is ready”, may depend on a contextually-determined completion. Semantics and Pragmatics 8/4/10 Page 2 • The interpretation of a sentence containing a discourse particle such as “too”, as in “Dennis is having dinner in London tonight too”, may depend on a contextually determined set of background propositions (Gauker 2008a). • The interpretation of a sentence employing metonymy, such as “The ham sandwich wants his check”, depends on a contextually-determined relation of reference-shifting. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Reference and Sense

REFERENCE AND SENSE y two distinct ways of talking about the meaning of words y tlkitalking of SENSE=deali ng with relationshippggs inside language y talking of REFERENCE=dealing with reltilations hips bbtetween l. and the world y by means of reference a speaker indicates which things (including persons) are being talked about ege.g. My son is in the beech tree. II identifies persons identifies things y REFERENCE-relationship between the Enggplish expression ‘this p pgage’ and the thing you can hold between your finger and thumb (part of the world) y your left ear is the REFERENT of the phrase ‘your left ear’ while REFERENCE is the relationship between parts of a l. and things outside the l. y The same expression can be used to refer to different things- there are as many potential referents for the phrase ‘your left ear’ as there are pppeople in the world with left ears Many expressions can have VARIABLE REFERENCE y There are cases of expressions which in normal everyday conversation never refer to different things, i.e. which in most everyday situations that one can envisage have CONSTANT REFERENCE. y However, there is very little constancy of reference in l. Almost all of the fixing of reference comes from the context in which expressions are used. y Two different expressions can have the same referent class ica l example: ‘the MiMorning St’Star’ and ‘the Evening Star’ to refer to the planet Venus y SENSE of an expression is its place in a system of semantic relati onshi ps wit h other expressions in the l. -

The Meaning of Language

01:615:201 Introduction to Linguistic Theory Adam Szczegielniak The Meaning of Language Copyright in part: Cengage learning The Meaning of Language • When you know a language you know: • When a word is meaningful or meaningless, when a word has two meanings, when two words have the same meaning, and what words refer to (in the real world or imagination) • When a sentence is meaningful or meaningless, when a sentence has two meanings, when two sentences have the same meaning, and whether a sentence is true or false (the truth conditions of the sentence) • Semantics is the study of the meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences – Lexical semantics: the meaning of words and the relationships among words – Phrasal or sentential semantics: the meaning of syntactic units larger than one word Truth • Compositional semantics: formulating semantic rules that build the meaning of a sentence based on the meaning of the words and how they combine – Also known as truth-conditional semantics because the speaker’ s knowledge of truth conditions is central Truth • If you know the meaning of a sentence, you can determine under what conditions it is true or false – You don’ t need to know whether or not a sentence is true or false to understand it, so knowing the meaning of a sentence means knowing under what circumstances it would be true or false • Most sentences are true or false depending on the situation – But some sentences are always true (tautologies) – And some are always false (contradictions) Entailment and Related Notions • Entailment: one sentence entails another if whenever the first sentence is true the second one must be true also Jack swims beautifully. -

Predicate Logic

Logical Form & Predicate Logic Jean Mark Gawron Linguistics San Diego State University [email protected] http://www.rohan.sdsu.edu/∼gawron Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 1/30 Predicates and Arguments Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 2/30 Logical Form The Logical Form of English sentences can be represented by formulae of Predicate Logic, What do we mean by the logical form of a sentence? We mean: we can capture the truth conditions of complex English expressions in predicate logic, given some account of the denotations (extensions) of the simple expressions (words). Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 3/30 The Leading Idea: Extensions Nouns, verbs, and adjectives have predicates as their translations. What does ’predicate’ mean? ’Predicate’ means what it means in predicate logic. Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 4/30 Intransitive verbs Translating into predicate logic (1) a. Johnwalks. b. walk(j) (2) a. [[j]] = John b. “The extension of ’j’ is the individual John.” c. [[walk]] = {x | x walks } d. “The extension of ’walk’ is the set of walkers” (3) a. [[John walks]] = [[walk(j)]] b. [[walk(j)]] = true iff [[j]] ∈ [[walk]] Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 5/30 Extensional denotations • Remember two kinds of denotation. For work with logic, denotations are always extensions. • We call a denotation such as [[walk]] (a set) an extension, because it is defined by the set of things the word walk describes or “extends over” • The denotation [[j]] is also extensional because it is defined by the individual the word John describes. • Next we extend extensional denotation to transitive verbs, nouns, and sentences. -

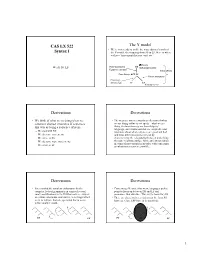

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Prosodic Focus∗

Prosodic Focus∗ Michael Wagner March 10, 2020 Abstract This chapter provides an introduction to the phenomenon of prosodic focus, as well as to the theory of Alternative Semantics. Alternative Semantics provides an insightful account of what prosodic focus means, and gives us a notation that can help with better characterizing focus-related phenomena and the terminology used to describe them. We can also translate theoretical ideas about focus and givenness into this notation to facilitate a comparison between frameworks. The discussion will partly be structured by an evaluation of the theories of Givenness, the theory of Relative Givenness, and Unalternative Semantics, but we will cover a range of other ideas and proposals in the process. The chapter concludes with a discussion of phonological issues, and of association with focus. Keywords: focus, givenness, topic, contrast, prominence, intonation, givenness, context, discourse Cite as: Wagner, Michael (2020). Prosodic Focus. In: Gutzmann, D., Matthewson, L., Meier, C., Rullmann, H., and Zimmermann, T. E., editors. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley{Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118788516.sem133 ∗Thanks to the audiences at the semantics colloquium in 2014 in Frankfurt, as well as the participants in classes taught at the DGFS Summer School in T¨ubingen2016, at McGill in the fall of 2016, at the Creteling Summer School in Rethymnos in the summer of 2018, and at the Summer School on Intonation and Word Order in Graz in the fall of 2018 (lectures published on OSF: Wagner, 2018). Thanks also for in-depth comments on an earlier version of this chapter by Dan Goodhue and Lisa Matthewson, and two reviewers; I am also indebted to several discussions of focus issues with Aron Hirsch, Bernhard Schwarz, and Ede Zimmermann (who frequently wanted coffee) over the years. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Context Pragmatics Definition of Pragmatics

Pragmatics • to ask a question: Maybe Sandy’s reassuring you that Kim’ll get home okay, even though she’s walking home late at night. Sandy: She’s got more than lipstick and Kleenex in that purse of hers. • What is Pragmatics? You: Kim’s got a knife? • Context and Why It’s Important • Speech Acts – Direct Speech Acts – Indirect Speech Acts • How To Make Sense of Conversations – Cooperative Principle – Conversational Maxims Linguistics 201, Detmar Meurers Handout 3 (April 9, 2004) 1 3 Definition of Pragmatics Context Pragmatics is the study of how language is used and how language is integrated in context. What exactly are the factors which are relevant for an account of how people use language? What is linguistic context? Why must we consider context? We distinguish several types of contextual information: (1) Kim’s got a knife 1. Physical context – this encompasses what is physically present around the speakers/hearers at the time of communication. What objects are visible, where Sentence (1) can be used to accomplish different things in different contexts: the communication is taking place, what is going on around, etc. • to make an assertion: You’re sitting on a beach, thinking about how to open a coconut, when someone (2) a. Iwantthat book. observes “Kim’s got a knife”. (accompanied by pointing) b. Be here at 9:00 tonight. • to give a warning: (place/time reference) Kim’s trying to bully you and Sandy into giving her your lunch money, and Sandy just turns around and starts to walk away. She doesn’t see Kim bring out the butcher knife, and hears you yell behind her, “Kim’s got a knife!” 2 4 2.