Rudy Burckhardt's a Walk Through Astoria and Other Places in Queens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIFTY-ONE YEARS of FILM by RUDY BURCKHARDT to BE SCREENED at Moma BEGINNING FEBRUARY 6

The MuSeUITI Of Modem Art For Immediate Release January 1987 FIFTY-ONE YEARS OF FILM BY RUDY BURCKHARDT TO BE SCREENED AT MoMA BEGINNING FEBRUARY 6 The unprecedented fifty-one year career of independent filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt will be celebrated in a major film retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art, beginning Friday, February 6, 1987. Mr. Burckhardt, who is also a noted photographer and painter, will introduce the exhibition with a program of films entitled "The Streets of New York" on February 6 at 6:30 p.m. THE FILMS OF RUDY BURCKHARDT has been organized by Laurence Kardish, curator in the Museum's Department of Film, and the novelist and essayist Phillip Lopate, who have arranged sixty-seven films into fourteen thematically-related programs. The exhibition includes Mr. Burckhardt's first film, 145 West 21 (1936), with Aaron Copland, Paul Bowles, Paula Miller, and Virgil Thomson, and his most recent, Digital Venus (1987). The films in the exhibition include both fiction and poetic documentaries, revealing Mr. Burckhardt's lyrical eye and gentle playfulness, especially in his depiction of New York City street scenes and his "travel diaries." He has created several short comedies in collaboration with a wide variety of New York City artists, including the painters Alex Katz and Red Grooms, and the poets John Ashbery and Edwin Denby. In addition, he made films with the late surrealist artist and filmmaker Joseph Cornell and with the dancers Paul Taylor and Douglas Dunn. Concurrent with the Museum's film exhibition are shows of Mr. Burckhardt's paintings at the Blue Mountain Gallery, 121 Wooster Street, New York City, February 6-25, and photographs at the Brooke Alexander Gallery, 59 Wooster Street, New York City, February 10-March 7. -

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many Preface by Dominique Fourcade Text by Charles Bernstein Salander-O’Reilly Galleries New York This catalogue accompanies an exhibition from September 5–28, 2002 at Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, LLC 20 East 79 Street New York, NY 10021 Tel (212) 879-6606 Fax (212) 744-0655 www.salander.com Monday–Saturday 9:30 to 5:30 © 2002 Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, LLC ISBN: 0 -158821-110-X Photography: Paul Waldman Design: Lawrence Sunden, Inc. Printing: The Studley Press TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 7 Dominique Fourcade Mimi Gross 9 Charles Bernstein Plates 21 Chronology 42 The artist in her studio. Photo: Henry Jesionka. >#< PREFACE Dominique Fourcade Charm of the Many, such a derangement, does not mean that many were charming, nor does it mean that many have a charm. It alludes to a surprise: in the act of painting many a dif- ferent one lies a charm, single, inborn, and the painter is exposed. Is acted. It has to do with unexpectable sameness, it is serendipitous as well as recalcitrant and alarming. It lurks, very real, not behind but in front of the surfaces. It amounts to a lonesome surface, the surface of portraiture, and deals with an absence, because one does not portray life, death is the subject. Death is the component and the span, the deeper one portrays the more it dawns on us. A sameness, not opaque, with a great variety of reso- nances, a repeated syncope. Charm of the Many is to be sensed, obviously, under the light of Mimi’s own Coptic ways, Fayoumesque, on the arduous path of appearance. -

Rudy Burckhardt – in the Jungle of the Big City Photographs and Films 1932 – 1959

October 2014 Press Announcement Rudy Burckhardt – In the Jungle of the Big City Photographs and Films 1932 – 1959 Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, 25 October 2014 to 15 February 2015 Press preview: 24 October 2014, 10 a.m. to 12 noon, opening: from 6 p.m. The Swiss photographer Rudy Burckhardt (1914-1999) arrived in New York for the first time as a 21-year-old and immediately decided to stay. Overwhelmed by the sheer size of the metropolis, the architectural diversity and the hustle and bustle on the streets, he began to process his impressions in photographs and films. The photographs and short films he produced until the early 1950s are a combination of straightforwardness and formal strictness, contrasting perspectives, the inclusion of chance as well as lyrical concentration, all of which make up a radically modern pictorial language which was way ahead of its time then, but surprises and fascinates us all the more today. On the occasion of his 100th birthday, the Fotostiftung Schweiz is presenting the exhibition “Rudy Burckhardt – In the Jungle of the Big City”, providing an opportunity to discover anew the photographic and filmic oeuvre of that highly individual artist. Rudy Burckhardt never really felt at home in the established patrician family into which he was born in Basel in 1914. At an early age he preferred to hang around in the slightly disreputable area of Kleinbasel, instead of seeking a social position in what was referred to in Basel as the “Daig” (“dough”), meaning the upper echelons of society. Around the same time he became interested in the new pictorial medium of photography, which was very much in the air in the 1930s. -

Red Grooms Artist CV

Marlborough RED GROOMS 1937— Born in Nashville, Tennessee. The artist lives and works in New York, New York. Education 1957— Hans Hoffman School of Fine Arts, Provincetown, Massachusetts 1956— George Peabody College for Teachers, Nashville, Tennessee The New School, New York, New York 1955— School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Solo Exhibitions 2021— Red Grooms, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2020— Ruckus Rodeo, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, Texas 2018— Handiwork, 1955 – 2018, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Red Grooms: A Retrospective, Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee 2017— New York On My Mind, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2016— Lincoln on the Hudson by Red Grooms, Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York Red Grooms: Traveling Correspondent, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee 2015— Red Grooms: The Blue & The Gray, Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee; traveled to Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York 2014— Red Grooms: Torn from the Pages II, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York Red Grooms: Beware a Wolf in the Alley, Marlborough Broome Street, New York, New York Marlborough 2013— Red Grooms’ New York City, Children’s Museum of Manhattan, New York, New York Red Grooms: What’s the Ruckus, Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, Brattleboro, Vermont Red Grooms: Larger Than Life, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut 2012— Torn from the Pages, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2011— Red Grooms, New York: 1976-2011, Marlborough -

Edith Schloss Burckhardt Archive Featuring: Rudy Burckhardt, Edwin Denby, Francesca Woodman, and Alvin Curran

Edith Schloss Burckhardt Archive Featuring: Rudy Burckhardt, Edwin Denby, Francesca Woodman, and Alvin Curran Avant-garde composer and musician Alvin Curran has written about his meeting with artist, writer, and critic Edith Schloss Burckhardt during his first years in Rome: “In that same settling-in period I met Edith Schloss, an Offenbach-born New York painter just divorced from photographer-painter Rudy Burckhardt. She arrived on a cloud of combustible materials which included the entire New York Abstract Expressionist movement, the Cedar Bar, Art News, MOMA, the Art Students League and Balanchine Stravinsky the Carters Edwin Denby de Kooning Twombly Feldman Cage Brown Rothko Cunningham Pollack her beloved Morandi and of course ‘Piero’ (della Francesca)...” The Edith Schloss Burckhardt Archive offers an extraordinary opportunity for research into multiple areas of scholarship, especially unique insight into the lives and experiences of women in the art world, an American artist’s expat life in Rome from the 1960s–2010s, the New York School of painters and poets, and a particularly rich and far-reaching, vein of the avant-garde and experimental music world, to name a few. Copy print of the 1949 Rudy Burckhardt photomontage “Over the Roofs of Chelsea” created for the exhibition with Helen DeMott, Lucia Vernarelli and ESB at the Pyramid Gallery. The three close friends were called “Chelsea Girls” by Edwin Denby. The Archive contains extensive correspondence with both DeMott and Vernarelli. Foreground: DeMott, ESB (pregnant with her son Jacob), and Vernarelli. Edith Schloss Burckhardt (1919 – 2011) Edith Schloss was born in Offenbach, Germany. She was sent to France and England to learn languages and, in 1936, attended a private school in Florence where she first fell in love with Italy. -

Oral History Interview with Yvonne Jacquette

Oral history interview with Yvonne Jacquette This interview is part of the Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women in the Visual Arts Project, funded by the A G Foundation. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Yvonne Jacquette AAA.jacque10 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Yvonne Jacquette Identifier: AAA.jacque10 Date: 2010 Oct. 19-21 Creator: Jacquette, Yvonne (Interviewee) McElhinney, James Lancel, 1952- (Interviewer) Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women -

Whimsy, the Avant-Garde and Rudy Burckhardt's and Kenneth Koch's

Whimsy, the Avant-Garde and Rudy Burckhardt’s and Kenneth Koch’s The Apple Daniel Kane Part 1 - Alice throws my shirt onto the cabin roof ‘Little Fawn Like Alice’ or, more simply, ‘Loofah’ is what my friends and I used to call Alice when we were undergraduate students at Marlboro College back in the late 1980s. Because Alice resembled Tin-Tin (sexy) and was tremendously intelligent and funny, I considered myself one of the luckiest guys around when she consented to become my beloved after months of often desperate courtship on my part. We moved in to a cabin in the middle of the Vermont woods, and tried our best to live and love together. One summer’s day we drove down to Brattleboro to go shopping. On the drive back to the cabin I took my shirt off. As we pulled up to the cabin, something happened that has resonated with me ever since…something I think about constantly even though it happened over twenty years ago now…this is how Alice recalls it: You were wearing that horrible mustard-colored misshapened cotton mock turtle neck you wore every fucking day that made you look green and homeless. You had just gotten back from Czechoslovakia. I was driving and you were next to me. It was starting to get hot and you took off the shirt in the car and put it between our seats. We pulled up to the cabin. I grabbed the shirt as we were getting out of the car and tossed it onto the roof of the cabin. -

An Afternoon in Astoria by Rudolph Burckhardt

An afternoon in Astoria By Rudolph Burckhardt Author Burckhardt, Rudy Date 2002 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers ISBN 0870704362 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/152 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art ERNOON IN ASTORIA BY RUDOLPH BURCKHARDT v—-" . ?*! . T^'p'l'i^iflT 'f rff--r 1 rap . AN AFTERNOON IN ASTORIA SOCONY . \CU' M I^Heauto BATTERIES I TIRES ACCESSORIES«r LUBRICATIONp M* AN AFTERNOON IN ASTORIA BY RUDOLPH BURCKHARDT TheMuseum of ModernArt, NewYork Distributedby D.A.P./DistributedArt Publishers, New York Avc^1 Kn>j\ hoo THIS BOOK IS PUBLISHED ON THE OCCASIONOF THE OPENING OF MOMA QNS, THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART'S FACILITY IN QUEENS, NEW YORK Thepublication is supportedby a generousgrant from Adam Bartos Producedby the Departmentof Publications,The Museum of ModernArt,New York Editedby DavidFrankel Designedby Hsien-YIinngrid Chou Productionby ChrisZichello Directdigit al-capturescans by KellyBenjamin,Kimberly Marshall Pancoastand , John Wronn Printedand bound by TrifolioS.R.L.V,erona Typeset in FBInterstate Printedon 170 gsm Xenon Scheufelen Copyright© 2002The Museum of ModernArt, NewYork. All rightsreserved Photographs© 2002 The Estate of RudolphBurckhardt Thepoem on p.33 is © 2002The Estate of EdwinDenby Libraryof CongressControl Number:2002103314 ISBN:0-87070-436-2 Publishedby TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019 Distributedin the UnitedStates and Canada by D.A.P./DistributAedrt Publishers,New York Distributedoutside the UnitedStates and Canada by Thames& HudsonLtd, London Cover:Rudy BurckhardtUnt. -

Artnet Magazine

An Afternoon at the Met - artnet Magazine Auctions Artists Galleries Auction Houses Events News In artnet Magazine AN AFTERNOON News Reviews AT THE MET Features by Christopher Sweet Books As wars sputter and flare and markets stagger downward and the fevered globe turns on its People uneasy axis, art nonetheless continues to offer its Videos more enduring consolations. Strolling through the Metropolitan Museum the other Sunday afternoon, I Horoscope went for a quick last look at Giorgio Morandi’s Newsletter quivering bottles, bowls, and boxes, and then to see the newly acquired work by Valentin de Boulogne, Spencer’s Art Law Journal The Lute Player (ca. 1626). The painting of a musician or, as the picture’s label states, "a soldier Valentin de Boulogne of fortune singing a love madrigal," resonates with The Lute Player Watteau’s Mezzetin (ca. 1718–20), in the next ca. 1626 gallery, as well as the central figure of Caravaggio’s Metropolitan Museum of Art Musicians of ca. 1595, which I didn’t find on view that day. The Mezzetin is plaintive and full of yearning where Valentin’s musician is more intent in his purpose of seduction while Caravaggio’s lute player would appear to be the more passive object of seduction. From the European Paintings galleries, I made my way across to the recently expanded 19thcentury galleries toward the museum’s new Henri Matisse acquisition. Along the way, I was still pleased to see the expatriates Cassatt, Whistler and Sargent where they belong, among their European peers. Their usual exile in the American Wing is unfortunate, but at least while the American galleries undergo renovations, one can see Madame X, Theodore Duret and the rest in a more fitting context. -

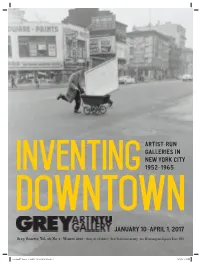

Inventing Downtown

ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY Inventing 1952–1965 Downtown JANUARY 10–APRIL 1, 2017 Grey Gazette, Vol. 16, No. 1 · Winter 2017 · Grey Art Gallery New York University 100 Washington Square East, NYC InventingDT_Gazette_9_625x13_12_09_2016_UG.indd 1 12/13/16 2:15 PM Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Courtesy the photographer and Magnum Photos Aldo Tambellini, We Are the Primitives of a New Era, from the Manifesto series, c. 1961. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @NYUGrey InventingDowntown # Aldo Tambellini Archive, Salem, Massachusetts This issue of the Grey Gazette is funded by the Oded Halahmy Endowment for the Arts; the Boris Lurie Art Foundation; the Foundation for the Arts. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; the Art Dealers Association Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 is organized by the Grey Foundation; Ann Hatch; Arne and Milly Glimcher; The Cowles Art Gallery, New York University, and curated by Melissa Charitable Trust; and the Japan Foundation. The publication Rachleff. Its presentation is made possible in part by the is supported by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art; the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Additional support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Grey Art Gallery’s Director’s Circle, Inter/National Council, and Visual Arts; the S. & J. Lurje Memorial Foundation; the National Friends; and the Abby Weed Grey Trust. GREY GAZETTE, VOL. 16, NO. 1, WINTER 2017 · PUBLISHED BY THE GREY ART GALLERY, NYU · 100 WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST, NYC 10003 · TEL. -

Yvonne Jacquette

Yvonne Jacquette Born Pittsburgh, PA, 1934 Education 1952-56 Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI Solo Exhibitions 2019 Yvonne Jacquette: Daytime New York, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Yvonne Jacquette: Paintings 1981-2016, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2015 Yvonne Jacquette; Aerials, Seraphin Gallery, Philadelphia, PA 2014 Yvonne Jacquette: The High Life, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Yvonne Jacquette, Aerials: Paintings, Prints, Pastels, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockport, ME Yvonne Jacquette, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2009-10 Yvonne Jacquette: The Complete Woodcuts, 1987 – 2009, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY; Springfield Art Museum, Springfield, MO. 2008 Picturing New York: Nocturnes by Yvonne Jacquette, Museum of the City of New York, New York, NY Yvonne Jacquette, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Yvonne Jacquette: Arrivals and Departures, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Yvonne Jacquette: Paintings and Works on Paper, Springfield Art Museum, Springfield, MO 2003 DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 2002-03 Aerial Muse: The Art of Yvonne Jacquette, Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, CA; Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME; Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, UT; Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY 2000 Yvonne Jacquette - Evening: Chicago and New York, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY 1998 Yvonne Jacquette: Maine Aerials, Art Gallery, University of Southern Maine, Gorham, ME Paintings and Works on Paper by Yvonne Jacquette, Hollins Art Gallery, Hollins -

Oral History Interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 January 14

Oral history interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 January 14 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview RB: . .for rent signs in every block then a little later I got married and lived across the street in the same block with Edith Schloss and Edwin Denbykept living there and now fifty-five years later or so my son lives there. Most of the time it was illegal to live there. MS: It's right near here. RB: On 21st Street. And this is an interesting little item, believe it or not. When we got there we got a telephone and the number was Chelsey 25097 and the telephone number is still the same except instead of Chelsey now it's 242-5097. MS: That's extraordinary in this city that you would have that all that time. So Denby had lived there all that time. RB: He lived there until he died about ten years ago and now my son lives there. Now he actually got it legal. He finally got together with the landlord and it's legal to live in lofts. At that time for a long time you couldn't live in lofts legally and then there was something called AIR, Artists in Residence and I remember Edwin had to pretend to be a painter and he had to make some paintings, and an inspector came.