Artnet Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D. Rowland MAY 11, 2017 ISSUE The Guardian of Mercy: How an Extraordinary Painting by Caravaggio Changed an Ordinary Life Today by Terence Ward Arcade, 183 pp., $24.99 Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 7, 2016–January 22, 2017; and the Musée du Louvre, Paris, February 20–May 22, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Annick Lemoine and Keith Christiansen Metropolitan Museum of Art, 276 pp., $65.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, October 12, 2016–January 15, 2017; the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, February 11–May 14, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Letizia Treves and others London: National Gallery, 208 pp., $40.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) The Seven Acts of Mercy a play by Anders Lustgarten, produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon- Avon, November 24, 2016–February 10, 2017 Caravaggio: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 1607 Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples Two museums, London’s National Gallery and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, mounted exhibitions in the fall of 2016 with the title “Beyond Caravaggio,” proof that the foul-tempered, short-lived Milanese painter (1571–1610) still has us in his thrall. The New York show, “Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio,” concentrated its attention on the French immigrant to Rome who became one of Caravaggio’s most important artistic successors. The National Gallery, for its part, ventured “beyond Caravaggio” with a choice display of Baroque paintings from the National Galleries of London, Dublin, and Edinburgh as well as other collections, many of them taken to be works by Caravaggio when they were first imported from Italy. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

The Representation of Roma in Major European Museum Collections

The Council of Europe is a key player in the fight to respect THE REPRESENTATION OF ROMA the rights and equal treatment of Roma and Travellers. As such, it implements various actions aimed at combating IN MAJOR EUROPEAN discrimination: facilitating the access of Roma and Travellers to public services and justice; giving visibility to their history, MUSEUM COLLECTIONS culture and languages; and ensuring their participation in the different levels of decision making. Another aspect of the Council of Europe’s work is to improve the wider public’s understanding of the Roma and their place in Europe. Knowing and understanding Roma and Travellers, their customs, their professions, their history, their migration and the laws affecting them are indispensable elements for interpreting the situation of Roma and Travellers today and understanding the discrimination they face. This publication focuses on what the works exhibited at the Louvre Museum tell us about the place and perception of Roma in Europe from the15th to the 19th centuries. Students aged 12 to 18, teachers, and any other visitor to the Louvre interested in this theme, will find detailed worksheets on 15 paintings representing Roma and Travellers and a booklet to foster reflection on the works and their context, while creating links with our contemporary perception of Roma and Travellers in today’s society. 05320 0 PREMS ENG The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights organisation. It comprises 47 member Volume I – The Louvre states, including all members of the European Union. Sarah Carmona All Council of Europe member states have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law. -

Rudy Burckhardt's a Walk Through Astoria and Other Places in Queens

1 Rudy Burckhardt’s A Walk Through Astoria and Other Places in Queens By Christopher Sweet August 2017 The photographer and filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt (1914–1999) arrived in New York in 1935 from his native Switzerland, and was quickly immersed in avant-garde circles and the New York School. His then partner and life-long friend, the poet and dance critic Edwin Denby (1903– 1983), whom he had first met in Basel the year before, introduced him to Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, Paul Bowles, and others and together they soon encountered and befriended their neighbor, an unknown painter at the time, Willem de Kooning. The two, together and separately, would become essential figures in the downtown cultural bohemian scene over the next several decades, with friends and artistic collaborators including John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Franz Kline, Joseph Cornell, Larry Rivers, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, and many others. Burckhardt was initially daunted by what he called the “grandeur and ceaseless energy” of New York City, and it would take him two to three years before he began to photograph the city. In the meantime, he made his first film in 1936, a silent comedy set largely in his Chelsea loft and featuring Copland, Bowles, Thomson, and others. By 1939 he had created his first masterpiece, the photographic album New York, N. Why?, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The work consists of 67 photographs arranged and sequenced in three main movements, focusing on street facades, shops and signage, and the ebb and flow of people in the streets, along with six sonnets by Edwin Denby and an excerpt from a New Yorker article. -

Artist Bios Alex Katz Is the Author of Invented Symbols

Artist Bios Alex Katz is the author of Invented Symbols: An Art Autobiography. Current exhibitions include “Alex Katz: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art” at the Nassau County Museum of Art and “Alex Katz: Beneath the Surface” at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. Jan Henle grew up in St. Croix and now works in Puerto Rico. His film drawings are in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. His collaborative film with Vivien Bittencourt, Con El Mismo Amor, was shown at the Gwang Ju Biennale in 2008 and is currently in the ikono On Air Festival. Juan Eduardo Gómez is an American painter born in Colombia in 1970. He came to New York to study art and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1998. His paintings are in the collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick. He was awarded The Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award from American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2007. Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1914 and moved to New York in 1935. From then on he was at or near the center of New York’s intellectual life, counting among his collaborators Edwin Denby, Paul Bowles, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, and many others. His work has been the subject of exhibitions at the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, the Museum of the City of New York, and, in 2013, at Museum der Moderne Salzburg. -

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. 2nd Fridays 10 a.m. – 9 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. -

Baroque Women: Pictures of Purity and Debauchery

Baroque Women: Pictures of Purity and Debauchery By: Analise Austin, Mentor: Dr. Niria Leyva-Gutierrez Arts Management College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Abstract Throughout the Baroque period, and much of the world’s artistic history, women have been portrayed as either saints or sinners, pictures of purity or wicked temptresses. Women have known little middle ground historically, despite occupying diverse roles and representing half the world’s population. In Catholic nations, where most art was religious in nature, Baroque women met the dichotomy of being cast as either saint or sinner, mother or virgin. Whether tender images of Mary as a doting mother, saints tending to wounded souls, or virgins pure in body and spirit, the image of a good woman was docile, kind and soft. If not soft and docile, women were depicted as whores, adulteresses and tricksters, wicked temptations to good men. There was little in between for Catholic representation of the woman at this time. In the northern, protestant states however, alternate depictions of women began to emerge in the growing prominence of genre painting. It is here women were attributed with a slightly greater range of characters, perhaps a housewife, young bride, or an elderly matron. While not restrained to mere saint or sinner, women were still chained to their relation to the men around them. Their depicted identities remained flat in the accepted social roles of their gender and were rarely see outside of a domestic sphere. Whether religious or genre, women were nearly always represented in terms of their value or relation to men. -

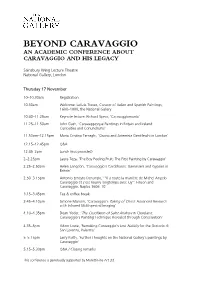

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics the Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet

Nuncius 31 (2016) 288–331 brill.com/nun The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics The Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet Susana Gómez López* Faculty of Philosophy, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract In his excellent work Anamorphoses ou perspectives curieuses (1955), Baltrusaitis con- cluded the chapter on catoptric anamorphosis with an allusion to the small engraving by Hans Tröschel (1585–1628) after Simon Vouet’s drawing Eight satyrs observing an ele- phantreflectedonacylinder, the first known representation of a cylindrical anamorpho- sis made in Europe. This paper explores the Baroque intellectual and artistic context in which Vouet made his drawing, attempting to answer two central sets of questions. Firstly, why did Vouet make this image? For what purpose did he ideate such a curi- ous image? Was it commissioned or did Vouet intend to offer it to someone? And if so, to whom? A reconstruction of this story leads me to conclude that the cylindrical anamorphosis was conceived as an emblem for Prince Maurice of Savoy. Secondly, how did what was originally the project for a sophisticated emblem give rise in Paris, after the return of Vouet from Italy in 1627, to the geometrical study of catoptrical anamor- phosis? Through the study of this case, I hope to show that in early modern science the emblematic tradition was not only linked to natural history, but that insofar as it was a central feature of Baroque culture, it seeped into other branches of scientific inquiry, in this case the development of catoptrical anamorphosis. Vouet’s image is also a good example of how the visual and artistic poetics of the baroque were closely linked – to the point of being inseparable – with the scientific developments of the period. -

FIFTY-ONE YEARS of FILM by RUDY BURCKHARDT to BE SCREENED at Moma BEGINNING FEBRUARY 6

The MuSeUITI Of Modem Art For Immediate Release January 1987 FIFTY-ONE YEARS OF FILM BY RUDY BURCKHARDT TO BE SCREENED AT MoMA BEGINNING FEBRUARY 6 The unprecedented fifty-one year career of independent filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt will be celebrated in a major film retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art, beginning Friday, February 6, 1987. Mr. Burckhardt, who is also a noted photographer and painter, will introduce the exhibition with a program of films entitled "The Streets of New York" on February 6 at 6:30 p.m. THE FILMS OF RUDY BURCKHARDT has been organized by Laurence Kardish, curator in the Museum's Department of Film, and the novelist and essayist Phillip Lopate, who have arranged sixty-seven films into fourteen thematically-related programs. The exhibition includes Mr. Burckhardt's first film, 145 West 21 (1936), with Aaron Copland, Paul Bowles, Paula Miller, and Virgil Thomson, and his most recent, Digital Venus (1987). The films in the exhibition include both fiction and poetic documentaries, revealing Mr. Burckhardt's lyrical eye and gentle playfulness, especially in his depiction of New York City street scenes and his "travel diaries." He has created several short comedies in collaboration with a wide variety of New York City artists, including the painters Alex Katz and Red Grooms, and the poets John Ashbery and Edwin Denby. In addition, he made films with the late surrealist artist and filmmaker Joseph Cornell and with the dancers Paul Taylor and Douglas Dunn. Concurrent with the Museum's film exhibition are shows of Mr. Burckhardt's paintings at the Blue Mountain Gallery, 121 Wooster Street, New York City, February 6-25, and photographs at the Brooke Alexander Gallery, 59 Wooster Street, New York City, February 10-March 7. -

A Bove the Pacific

Lieutenant Colonel William J. Horvat A bove the Pacific Printed and Published in the United States by Aero Publishers, Inc., 1966 ABOVE THE PACIFIC By LT. COL. WILLIAM J. HORVAT This is the first complete story of the flights “Above the Pacific” from the first Hawaiian balloon ascent in 1880 and the first Curtiss flights in1910 up to the prevent time (1966). Modern day coverage includes a discussion of the airlines that serve the area, as well as information on the satellite tracking facilities located on the island. This fascinating page of history includes the story of Hawaii’s vital role in the development of World Aviation History. Hawaii can truthfully be called the “Springboard to Aerospace” in the Pacific. As a halfway spot across the ocean, it has been used by sea-faring navigators for thousands of years; and the island’s strategic position in the midst of 5,000 miles of ocean has focused attention on this Garden Spot as an aid to aviation development. This authentic book is truthfully a documentary of flights “Above the Pacific.” Included are stories of the military interest, in addition to the civilian interest, in Hawaiian aviation. The succession of events is given in chronological order, with military as well as commercial activities being covered. An illustrated story of Pearl Harbor and World War II is also included. Editor’s Note: Above the Pacific was published by Aero Publishers, Inc. in 1966. The book is no longer in print. The publisher is no longer in business. The author Lt. Col. William J. -

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many Preface by Dominique Fourcade Text by Charles Bernstein Salander-O’Reilly Galleries New York This catalogue accompanies an exhibition from September 5–28, 2002 at Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, LLC 20 East 79 Street New York, NY 10021 Tel (212) 879-6606 Fax (212) 744-0655 www.salander.com Monday–Saturday 9:30 to 5:30 © 2002 Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, LLC ISBN: 0 -158821-110-X Photography: Paul Waldman Design: Lawrence Sunden, Inc. Printing: The Studley Press TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 7 Dominique Fourcade Mimi Gross 9 Charles Bernstein Plates 21 Chronology 42 The artist in her studio. Photo: Henry Jesionka. >#< PREFACE Dominique Fourcade Charm of the Many, such a derangement, does not mean that many were charming, nor does it mean that many have a charm. It alludes to a surprise: in the act of painting many a dif- ferent one lies a charm, single, inborn, and the painter is exposed. Is acted. It has to do with unexpectable sameness, it is serendipitous as well as recalcitrant and alarming. It lurks, very real, not behind but in front of the surfaces. It amounts to a lonesome surface, the surface of portraiture, and deals with an absence, because one does not portray life, death is the subject. Death is the component and the span, the deeper one portrays the more it dawns on us. A sameness, not opaque, with a great variety of reso- nances, a repeated syncope. Charm of the Many is to be sensed, obviously, under the light of Mimi’s own Coptic ways, Fayoumesque, on the arduous path of appearance.