AZERBAIJAN in the WORLD ADA Biweekly Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Republic of Azerbaijan Country Report

NCSEJ Country Report Email: [email protected] Website: NCSEJ.org Azerbaijan Zaqatala Quba Shaki Shabran Siazan Shamkir Mingachevir Ganja Yevlakh Sumqayit Hovsan Barda Baku Agjabedi Imishli Sabirabad Shirvan Khankendi Salyan Jalilabad Nakhchivan Lankaran m o c 60 km . s p a m - d 40 mi © 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Azerbaijan is secular republic. Approximately 93% of the country’s inhabitants have an Islamic background. About 5% are Christian. The remainder of the population belongs to various religions. Around 30,000 Jews live in Azerbaijan. History ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, also known as Azerbaijan People's Republic or Caucasus Azerbaijan in diplomatic documents, was the third democratic republic in the Turkic world and Muslim world, after the Crimean People's Republic and Idel-Ural Republic. Found in May 28, 1918 by Mahammad Amin Rasulzadeh. Ganja city was the Capital of Azerbaijan People’s Republic. Domestic Affairs ............................................................................................................................. 5 Azerbaijan is a constitutional republic with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The executive branch dominates and there is no independent judiciary. The President and the National Assembly are elected -

The State Oil Fund of the Republic of Azerbaijan Annual Report 2015 Content

THE STATE OIL FUND OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ANNUAL REPORT 2015 CONTENT 1. ABOUT SOFAZ 2 2. FACTS AT GLANCE 6 3. GOVERNANCE AND TRANSPARENCY 8 3.1. SOFAZ management 8 3.2. Transparency and accountability 14 4. NATIONAL ECONOMY AND SOFAZ 18 4.1. Macroeconomic development 18 4.2. SOFAZ Revenues 25 4.3. SOFAZ Expenditures 30 5. INVESTMENT REPORT 38 5.1. Investment Strategy 38 5.2. SOFAZ Investment portfolio 43 5.3. SOFAZ Investment 65 portfolio performance 5.4. Risk management 69 6. 2015 SOFAZ BUDGET EXECUTION 72 7. CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL 78 STATEMENTS OF SOFAZ APPENDIX 155 THE STATE OIL FUND OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN 01 ABOUT SOFAZ Objectives Legal framework for operating expenditures, are incorporated as part of an annual consolidated government budget presented SOFAZ’s activity is directed SOFAZ’s operations are to the Parliament for approval. to the achievement of the guided by the Constitution Thus, indirectly, all citizens following objectives: and laws of the Republic participate in the discussions of Azerbaijan, Presidential of the budget of SOFAZ. In decrees and resolutions, The State Oil Fund of the 1. Supporting macroeconomic compliance with this law, SOFAZ Statute and the Fund’s stability, participating in SOFAZ can only execute the regulations. ensuring fiscal-tax discipline expenditures envisaged by its Republic of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ) and decreasing dependence budget. on oil revenues while SOFAZ’s funding and stimulating development of withdrawal rules are clearly SOFAZ’s investment and was established in accordance the non-oil sector; defined by the “Statute risk management policies of State Oil Fund of the are defined by “Investment Republic of Azerbaijan” and Guidelines” and “Investment 2. -

Dr. Kaush Arha Senior Advisor for Strategic Engagement, United States Agency for International Development (Usaid)

FORUM SPEAKERS H.E. NOVRUZ MAMMADOV PRIME MINISTER OF AZERBAIJAN Mr. Novruz Mammadov was appointed Prime Minister of Azerbaijan in April 2018. Prior to his appointment, Mr. Mammadov was serving as an Assistant to the President of Azerbaijan on foreign issues as well as serving as Head of the Department of Lexicology and Stylistics of the French Language at the Azerbaijan University of Languages. Previously, Mr. Mammadov has served as a senior interpreter in Algeria and Guinea, Dean of Preparatory Faculty and Dean of Faculty of the French Language at the Azerbaijan Pedagogical Institute of Foreign Languages, Head of the Foreign Relations Department of the Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan, and interpreter to former President of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev. He was granted the rank of Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador by the decree of the President of Azerbaijan in January 2002 and in September 2005, Mr. Mammadov became a member of the National Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for UNESCO. Mr. Mammadov has received a number of honors including the French Legion d’Honneur Order by former French President Jacques Chirac, the Order of the Legion of Honor of Poland by former Polish President Lech Kaczyński, and the Order of Glory (Shohrat) by the decree of the President of Azerbaijan. MR. ELDAR ABAKIROV DEPUTY MINISTER OF ECONOMY OF KYRGYZSTAN Eldar Abakirov is Deputy Minister of Economy of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan and a Board Member of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Kyrgyzstan. From 2010-11 he worked as an expert at the National Bank of Kyrgyzstan and from 2003-10 he held several positions including Chief Specialist to the Deputy Director of the Treasury Department at JSC Bank Center Credit in Almaty, Kazakhstan. -

Country – Fact Sheet

Country – Fact Sheet General Official Name Republic of Azerbaijan Capital Baku Area 86,600 km2 Currency AZN (Manat) GDP AZN 70.13 billion (US $41.25 billion) [2017] GDP Growth Rate 0.1 % (2017) Unemployment 6% [2016 est.] GDP Per Capita AZN 7091 (US$4171) [2017] GDP Per Capita (PPP) US$ 17500 (2016 est.) Forest Cover 11.3% CO2 emissions 38 million Mt (2015 est.) Tourist Arrivals 2.69 million (2017) Population 10 million [2017] 9.95 million as on 1st September 2018 Population growth rate: 0.80 % Age Profile 0-14 years: 22.95% 15-24 years: 14.84% 25-54 years: 45.39% 55-64 years: 10.17% 65 years and over: 6.64% Life expectancy Total 72.8 years: Male: 69.7 years & Female: 76.1 years [2017 est.] Languages Azerbaijani (Azeri) (official) 92.5%, Russian 1.4%, Armenian 1.4%, other 4.7% (2009 est.) Ethnic groups Azerbaijani 91.6%, Lezgian 2%, Russian 1.3%, Armenian 1.3%, Talysh 1.3%, other 2.4% Religion Shia Muslim: 70%, Sunni Muslim: 23%, Russian Orthodox: 2.5%, Armenian Orthodox: 2.3%,others: 1.8% Internet Penetration 78.2% of population (2016 est.) Mobile phones 10.6 million Urbanisation urban population: 55.2% of total population (2017) Page 1 Exports US$ 13.81 billion [2017] Imports US$ 8.78 billion [2017] Main Trade Partners Italy, Turkey, Russia, China, Germany, Ukraine, USA (2017) Political Political Structure Presidential democracy with a directly elected President, who has a five year term. President appoints First Vice President and other Vice Presidents. Presidents appoints Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers to run the government. -

12 Azerbaijan: Going It Alone

12 Azerbaijan: Going It Alone Svante E. Cornell Over the past two decades, Azerbaijan has been among the countries most reti- cent to engage in integration projects among post-Soviet states. In fact, from the early 1990s onward, Azerbaijan resisted Russian efforts to integrate the country into various institutions. Since then, it has taken a position that can be generally described as being somewhat more accommodating than Georgia’s position toward Moscow, and somewhat more forward than those of Uzbeki- stan and Turkmenistan. In that context, it should come as no surprise that Azerbaijan has rejected offers to join the Customs Union or upcoming Eurasian Union, but it also has maintained a low profile on the matter. Economic Prospects Analysts have pointed to benefits as well as drawbacks that membership in the Customs Union and Eurasian Union would bring to Azerbaijan. These analyses are practically unanimous in noting that the negatives outweigh the positives. Even semi-official Russian analysts have acknowledged this, with one noting that “if Azerbaijan joins the Customs Union, that it is jointly with Turkey and this will not happen soon because of the nature of the Azerbaijani economy.”1 The benefits of Azerbaijan joining the Customs Union would essentially lie in greater access to the Russian market. Given that the Eurasian Union would bring free mobility of labor, it would, in theory, legalize the estimated up to two million Azerbaijani guest laborers in Russia, of which only a fraction have a legal presence—implying that Customs Union membership would remove one potential Russian instrument of pressure. -

Azerbaijan: Recent Developments and U.S

Azerbaijan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs February 22, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-522 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Azerbaijan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Azerbaijan is an important power in the South Caucasus by reason of its geographic location and ample energy resources, but it faces challenges to its stability, including the unresolved separatist conflict involving Nagorno Karabakh (NK). Azerbaijan enjoyed a brief period of independence in 1918-1920, after the collapse of the Tsarist Russian Empire. However, it was re-conquered by Red Army forces and thereafter incorporated into the Soviet Union. It re-gained independence when the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991. Upon independence, Azerbaijan continued to be ruled for a while by its Soviet-era leader, but in May 1992 he was overthrown and Popular Front head Abulfaz Elchibey was soon elected president. Military setbacks in suppressing separatism in the breakaway NK region contributed to Elchibey’s rise to power, and in turn to his downfall just over a year later, when he was replaced by Heydar Aliyev, the leader of Azerbaijan’s Nakhichevan region and a former communist party head of Azerbaijan. In July 1994, a ceasefire agreement was signed in the NK conflict. Heydar Aliyev served until October 2003, when under worsening health he stepped down. His son Ilkham Aliyev was elected president a few days later. According to the Obama Administration, U.S. assistance for Azerbaijan aims to develop democratic institutions and civil society, support the growth of the non-oil sectors of the economy, strengthen the interoperability of the armed forces with NATO, increase maritime border security, and bolster the country’s ability to combat terrorism, corruption, narcotics trafficking, and other transnational crime. -

Azerbaycan Nisan 2013

2013 AZERBAYCAN Ülke Bülteni DEİK / Türk –Azerbaycan İş Konseyi 0 Genel Bilgiler Resmi adı: Azerbaycan Cumhuriyeti Yönetim şekli: Cumhuriyet Ba şkent: Bakü Di ğer şehirler: Gence, Nahçıvan, Sumgayıt, Lenkeran, Şeki, Mingeçevir, Guba, Şirvan İdari yapı: 59 bölge (rayon), 11 şehir, 1 özerk cumhuriyet Kom şuları: Türkiye, İran, Gürcistan, Ermenistan, Rusya Federasyonu Yüzölçümü: 86,600 km 2 (Dünyanın en büyük yüzölçümüne sahip 112. ülkesi) Nüfus: 9,2 milyon (2011 yılı resmi sayım sonuçları itibariyle) Etnik da ğılım: Azeri (%90.6), Da ğıstanlı (%2.2), Rus (%1.8), Ermeni (%1.5) Dil: Azerbaycan Türkçesi Para birimi: Manat (Mart 2013 itibariyle 1 USD = 0.785 AZN, 1 EUR=1,03779 AZN ) Saat dilimi: Türkiye saati + 2 1 Konum Avrasya’nın Kafkaslar bölgesinde bulunan ve 86,600 km 2’lik bir yüzölçümüne sahip olan Azerbaycan, kuzeyde Rusya Federasyonu, güneyde İran, batıda Gürcistan ve Ermenistan ile kom şu olup, do ğuda ise Hazar Denizi ile çevrilidir. Nahçıvan Özerk Cumhuriyeti, kuzey ve doğusundan Ermenistan, güney ve batısından ise İran ile çevrili olup, kuzeybatıda Türkiye ile kısa bir sınırı bulunmaktadır. Azerbaycan’ın güneybatısındaki Da ğlık Karaba ğ bölgesi ise 1991 yılında Azerbaycan’dan ba ğımsızlı ğını ilan etmi şse de hiçbir ülke tarafından resmi olarak tanınmamakta ve uluslararası hukuk açısından Azerbaycan’ın bir parçası olarak kabul edilmektedir. Azerbaycan’ın toplam yüzölçümünün yüzde 55’ini tarım toprakları olu şturmakta, şehirler ise tüm ülkenin ancak yüzde 2.5’ini kaplamaktadır. Ülkenin yüzde 12’si ormanlık arazidir. Ba şkent ve Önemli Şehirler Resmi verilere göre yakla şık 2,5 milyonluk bir nüfusa sahip olan ba şkent Bakü, ülkenin aynı zamanda en büyük şehri ve hem Azerbaycan’ın hem de tüm Kafkasların en büyük limanı konumundadır. -

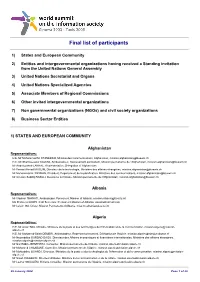

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

Hinter Der Glitzernden Fassade: Über Die Macht Der Informalität in Der Kaukasusrepublik Aserbaidschan Safiyev, Rail

www.ssoar.info Hinter der glitzernden Fassade: Über die Macht der Informalität in der Kaukasusrepublik Aserbaidschan Safiyev, Rail Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: transcript Verlag Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Safiyev, R. (2018). Hinter der glitzernden Fassade: Über die Macht der Informalität in der Kaukasusrepublik Aserbaidschan. (Edition Politik, 56). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839442234 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-70049-1 Rail Safiyev Hinter der glitzernden Fassade Edition Politik | Band 56 Rail Safiyev, geb. 1981, lehrt als Gastprofessor an der Fakultät der Vergleichen- den Politikwissenschaft an der Universität Bergen in Norwegen. Der Politik- wissenschaftler promovierte an der Freien Universität Berlin, forschte am Ins- titut für Iranistik der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und hatte Lehraufträge an der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena und an der FH des bfi Wien, wo er zu Themen Korruption und informale Herrschaftskultur im Kau- kasus lehrte. Rail Safiyev Hinter der glitzernden Fassade Über die Macht der Informalität in der Kaukasusrepublik Aserbaidschan Zugl.: Berlin, Freie Universität, Diss., 2017 Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution-NonCom- mercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Lizenz (BY-NC-ND). -

Turkic Council Monthly News Bulletin – May – June 2012 Prepared by Turkic Council Secretariat

TURKIC COUNCIL MONTHLY NEWS BULLETIN – MAY – JUNE 2012 PREPARED BY TURKIC COUNCIL SECRETARIAT Azerbaijan “No one favors current status-quo in Nagorno-Karabakh conflict” May 16 (AzerTAc). No one favored the current status-quo in Nagorno- Karabakh conflict, the chairperson of US House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs Ileana Ros-Lehtinen said. Ros-Lehtinen underlined that Azerbaijan`s role is increasing in exploration, development and transportation of energy resources. She welcomed diversification of energy transportation, and stressed that Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline has become a main transportation route which supplies the world with fuel. “It creates opportunity for the country to diversify the energy sources and our allies to avoid some dependence. New routes such as Nabucco will contribute to increase the strategic importance of Azerbaijan”, Ros- Lehtinen stated. Ros-Lehtinen pointed out importance of expansion of economic and trade ties between the countries, and said that the third meeting within the framework of the US-Azerbaijan partnership held in Washington brought new initiatives to civil aviation. The Committee chairperson described Azerbaijan as a `significant` partner of the US in the fight against force and extremism, and highlighted that there is a close cooperation between the US and Azerbaijan not only in the fields of prevention of terrorist attacks, but also proliferation of biological and nuclear weapons. “We are satisfied particularly with the exercises conducted for the security of the Caspian Sea”. Ros-Lehtinen also expressed concern over the incidents occurred in the border areas with Nagorno- Karabakh. “Two Azerbaijani soldiers were killed tragically in the shooting. Use of force remains this prolonged conflict unsettled”, added Ros-Lehtinen. -

Provisional List of Participants

SUM.INF/9/10/Rev.4 1 December 2010 ENGLISH only OSCE SUMMIT IN ASTANA ON 1 AND 2 DECEMBER 2010 PROVISIONAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS (Please submit any changes to the list of participants to [email protected] at your earliest convenience.) Country First name, family name Position Albania Bamir TOPIPresident Albania Edmond HAXHINASTO Minister of Foreign Affairs Albania Dashamir XHAXHIU Director of the Cabinet of the President Albania Ilir MELO Director of the Cabinet of the Minister Albania Spiro KOCI Director General of Security Issues and International Organizations, MFA Albania Edvin SHVARC Director of Information of the Office of the President/Interpreter Albania Ivis NOCKA Director of European Integration and Security Issues Albania Xhodi SAKIQI Head of the OSCE Section, MFA Albania Artur BUSHATI State Protocol Department, MFA Albania Hajrush KONI Military Adviser, Permanent Mission to the OSCE Albania Shkelzen SINANI Cameraman of the Office of the President Albania Fran KACORRI Security Officer of the President Germany Angela MERKEL Federal Chancellor Germany Christoph HEUSGEN Foreign Policy and Security Advisor to the Federal Chancellor Germany Jürgen SCHULZ Head of Division Germany Bernhard KOTSCH Deputy Head of the Federal Chancellor's Office Germany Simone LEHMANN-ZWIENER Federal Chancellor's Office Germany Petra KELLER Assistant to Mme Chancellor Germany Wolf-Ruthart BORN State Secretary of the Federal Foreign Office Germany Eberhard POHL Deputy Director General, Federal Foreign Office Germany Lothar FREISCHLADER Head of Division,