Otto Frank File Embargoed Until

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

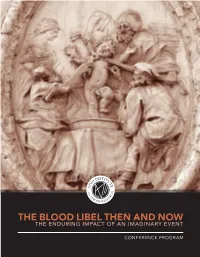

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed Until

Prepared for: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed until: February 14, 2007 at 10 AM EST BACKGROUND TO THE SITUATION OF JEWS IN THE NETHERLANDS UNDER NAZI OCCUPATION AND OF THE FAMILY OF OTTO FRANK By: David Engel Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies New York University Understanding the situation of Jews in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation, like understanding any aspect of the Holocaust, requires suspension of hindsight. No one could know in 1933, 1938, or even early 1941 that the Nazi regime would soon embark upon a systematic program aimed at killing each and every Jewish man, woman, and child within its reach. The statement is true of top German officials no less than it is of the Jewish and non-Jewish civilian populations of the twenty countries within the Nazi orbit and of the governments and peoples of the Allied and neutral countries. Although it is tempting to look back upon the history of Nazi anti-Jewish utterances and measures and to detect in them an ostensible inner logic leading inexorably to mass murder, the consensus among historians today is that when the Nazi regime came to power in January 1933 it had no clear idea how the so-called Jewish problem might best be solved. It knew only that, from its perspective, Jews presented a problem that would need to be solved sooner or later, but finding a long-term solution was initially not one of the regime's most immediate priorities. Between 1933-41 various Nazi agencies proposed different schemes for dealing with Jews. -

1 I N G H a M T Y N E W S 1 NEW C U M PROPOSE for Insurai

// you seek a delightful People run in dtbt but peninsula, look about you. craid out. —Motto of Michigan, 1 INGHAM TY NEWS 1 Seventy-fourth year, No. 52 INGHAM COUNTY NEWS, MASON, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 28,1933 12 Pages COMPLETES LONG SERVICE 12 Below Recoi'ded NEW cum PROPOSE LIS NIERESIG NEW YEAR At Disposal Plant The Steam Roller FOR INSURAi COMPANY PfiOMIAXCOLLEl Mason was one of the coldest Governor William A. Comstock called his democratic loaders together NPOLmCAlClfiCLES spots in the nation Wednesday Wednesday for the purpose of urging them to return to their homes ANNUAL MEETING AND ELEC HOSPITAL CHARGES ARE ONLY STATE TO BE BATTLE FIELD BE morning whon the inerciiry dipped and aid tho governor to put the "heat" on members of the Icgislaluro TION MONDAY, JANUARY 15. BILLS UNPAID. to 12° below zero on the offic TWEEN fMAJOR PARTIES. ial weather bureau thermometer at to return to the capitol next Wednesday and put over the administration Ohiirfior Lust Ameniliod In 1922—New Collection Of Delinquent Taxes And the disposal plant. The reading program for public works. "Notify your members that they are stand Alex Groosbock Seen .^s PosHlblo Re- publlciui Choice To Oppose Charter To Bo SlnipIUicdf. Endors Current Levy Aliling Coimty In waa taken at seven o'clock. Most ing in the wny of a steam roller that will crush them," urged the gover ed By Insurnnce OoinniLs.sl()n. Paying Claims. Grtvenior Cninstock. other readings in Michigan were nor to his henchmen. six and seven below zero. In accordance with recommenda Clarence W. -

On Dean W. Arnold's Writing . . . UNKNOWN EMPIRE Th E True Story of Mysterious Ethiopia and the Future Ark of Civilization “

On Dean W. Arnold’s writing . UNKNOWN EMPIRE T e True Story of Mysterious Ethiopia and the Future Ark of Civilization “I read it in three nights . .” “T is is an unusual and captivating book dealing with three major aspects of Ethiopian history and the country’s ancient religion. Dean W. Arnold’s scholarly and most enjoyable book sets about the task with great vigour. T e elegant lightness of the writing makes the reader want to know more about the country that is also known as ‘the cradle of humanity.’ T is is an oeuvre that will enrich our under- standing of one of Africa’s most formidable civilisations.” —Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, PhD Magdalene College, Cambridge, and Univ. of Frankfurt Great Nephew of Emperor Haile Selassie Imperial House of Ethiopia OLD MONEY, NEW SOUTH T e Spirit of Chattanooga “. chronicles the fascinating and little-known history of a unique place and tells the story of many of the great families that have shaped it. It was a story well worth telling, and one well worth reading.” —Jon Meacham, Editor, Newsweek Author, Pulitzer Prize winner . THE CHEROKEE PRINCES Mixed Marriages and Murders — Te True Unknown Story Behind the Trail of Tears “A page-turner.” —Gordon Wetmore, Chairman Portrait Society of America “Dean Arnold has a unique way of capturing the essence of an issue and communicating it through his clear but compelling style of writing.” —Bob Corker, United States Senator, 2006-2018 Former Chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee THE WIZARD AND THE LION (Screenplay on the friendship between J. -

Polish Jewry: a Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein

Polish Jewry: A Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein © YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2013 The old castle and the Maharsha synagogue in Ostrog, connected by an underground passage. Built in the 17th century, the synagogue was named after Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Eidels (1555 – 1631), author of the work Hidushei Maharsha. In 1795 the Jews of Ostrog escaped death by hiding in the synagogue during a military attack. To celebrate their survival, the community observed a special Purim each year, on the 7th of Tamuz, and read a scroll or Megillah which told the story of this miracle. Photograph by Alter Kacyzne. YIVO Archives. Courtesy of the Forward Association. A Haven from Persecution YIVO’s dedication to the study of the history of Jews in Poland reflects the importance of Polish Jewry in the Jewish world over a period of one thou- sand years, from medieval times until the 20th century. In early medieval Europe, Jewish communities flourished across a wide swath of Europe, from the Mediterranean lands and the Iberian Peninsu- la to France, England and Germany. But beginning with the first crusade in 1096 and continuing through the 15th century, the center of Jewish life steadily moved eastward to escape persecutions, massacres, and expulsions. A wave of forced expulsions brought an end to the Jewish presence in West- ern Europe for long periods of time. In their quest to find safe haven from persecutions, Jews began to settle in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, and parts of Ukraine, and were able to form new communities there during the 12th through 14th centuries. -

Proposal for the Registry of the Latin American And

1 MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Collection of the Center of Documentation and Investigation of the Ashkenazi Community in Mexico (16th to 20th Century) (Mexico) Ref N° 2008-11 PART A 1.- SUMMARY The Center of Documentation and Investigation of the Ashkenazi Community of Mexico keeps, preserves and disseminates the Ashkenazi culture, the culture of the Jewish people that was on the verge of disappearing during the Nazi era. It also safeguards the historic memory of the Jewish minority in Mexico that arrived from Central and Eastern Europe. Introduction. From the end of the 19th century the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe decided to emigrate towards America so as to find better living conditions. At that moment, large groups of Jews cut their ties to the lands in which they had developed a way of life, a language (Yiddish) and a manner of being: the Ashkenazi. Their former life ended violently and forever. At first, because of the pogroms unleashed by the Cossacks and Ukrainians, at the dawn of the 20th century by the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution, but mostly from the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 30s that led to the loss of six million people and thus to the disappearance of the Jewish communities of Central and Eastern Europe. At that moment, the Ashkenazi culture was threatened with extinction once the study centers and places for creating culture were wiped out during the Second World War. The few survivors of the Holocaust bore upon their shoulders the difficult task of rescuing themselves and their Jewish identity that had been so heavily menaced during the six years of war, the ghettos and the concentration and extermination camps. -

The Foreign Service Journal, January 1981

When you’re going overseas, you have enough to worry about without worrying about your insurance,too. Moving overseas can be a very traumatic time if you Moving overseas is simplified by the AFSA-sponsored don’t have the proper insurance. The fact is, the government insurance program for AFSA members. Our insurance will be responsible for only $15,000 worth of your belongings. program will take care of most of your worries. If any of your personal valuables such as cameras, jewelry, With our program, you can purchase as much property furs and fine arts are destroyed, damaged or stolen, you insurance as you feel you need at only 750 per $100, and it would receive not the replacement cost of the goods, but only covers you for the replacement cost of household furniture a portion of what you’d have to pay to replace them. and personal effects that are destroyed, damaged or stolen, Claims processes are another headache you shouldn't with no depreciation. You can also insure your valuable have to worry about. The government claims process is articles on an agreed amount basis, without any limitation. usually lengthy and requires investigation and AFSA coverage is worldwide, whether on business or documentation. pleasure. Should you have a problem, we provide simple, If you limit yourself to the protection provided under the fast, efficient claims service that begins with a simple phone Claims Act, you will not have worldwide comprehensive call or letter, and ends with payment in either U.S. dollars personal liability insurance, complete theft coverage or or local currency. -

Sephardic Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Updated September 2008 Sephardic Family History Research Guide Sephardim Spanish Jews, who had lived on the Iberian Peninsula since 6 B.C.E, began to call themselves Sephardim during the early Middle Ages. After the expulsions from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1497), Jews fled to numerous places within Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the New World. The word Sephardim came to refer to the Jews of these countries whose origins still remained in Spain or Portugal and who spoke Ladino and other Spanish regional dialects. Sephardic Genealogy Since the Sephardic world is so diverse and widespread, it is difficult to make generalizations about Sephardic genealogy. The sources, methods, and results of genealogical research on a family in Amsterdam, for example, differ greatly from research on a family in Aleppo or Salonika. However, there are several common characteristics: • Sephardic family names are much older than most Ashkenazi names. With Hebraic, Aramaic, Spanish or Arabic roots, Sephardic surnames are often traceable to the 11th century and even earlier. • In Sephardic naming customs, children can be named for both the living and the dead. Often, the firstborn son is named after the paternal grandfather, and the firstborn daughter is named after the paternal grandmother, so that given names may appear in every other generation. Resources at the Center for Jewish History General References Etsi (www.geocities.com/EnchantedForest/1321): journal of Sephardic genealogy (French/English) Genealogy Institute Faiguenboim, Guilherme, Paulo Valadares, and Anna Campagnano. Dicionário Sefaradi de Sobrenomes. (Sao Paulo, Fraiha, 2003) Genealogy Institute CS 3010 .F35 2003 Gandhi, Maneka. -

Ambassador Wells Stabler

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WELLS STABLER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 28, 1991 Copyright 1998 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Boston Massachusetts" Raised in the U.S. and abroad Harvard University Entered Foreign Service State Department - Inter American Affairs 19,1-19,3 Ecuadoran desk officer .elson Rockefeller involvement A/is South American strongholds Sumner 0ells 1ordell Hull 0artime 2black lists2 Post-0ar Programs 1ommittee - Assistant Secretary 19,, Political vs. economic discussions Secretary of State Stettinius Policy for post-3ar Europe and Asia 4erusalem - 5ice 1onsul 19,,-19,8 7etting there 0artime 4erusalem Environment 4e3s and Arabs 2truce2 8ing David Hotel e/plosion and aftermath 1onsulate jurisdiction 5isit to Emir Abdullah 1onsul 7eneral Pinkerton Anglo-American 1ommittee of In9uiry Operations and duties Terrorism British Arab sympathies OSS advisor 1 U.7A Partition Resolution British 3ithdra3al - 19,8 1onsulate guard detachment State unresponsive to needs 1onsul 7eneral Tom 0asson killed Political reporting ;ionists U.S. recognition of Israel Partition Plan - 19,7 Arab-Israel 3ar in 4erusalem 1onsular casualties 1ount Bernadotte - U. Mediator Amman 4ordan - American Representative - 1hargé d'Affaires 19,8-19,9 8ing Abdullah Sir Alec 8irkbride U.S. recognition of 4ordan 2Hashemite 8ingdom of 4ordan2 4ordan-British relations U. Trustee 1ouncil - U.S. Representative 1950 InternationaliAation of