'The Indian Image in the Black Mind:' Representing Native Americans In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Foundations of Oppression: the Antebellum South Appalachian Class Dynamic by Andrew Heggie

1 Foundations of Oppression: The Antebellum South Appalachian Class Dynamic By Andrew Heggie Introduction The American Republic was largely founded by a wealthy, speculative, land-owning class. This class wielded a great deal of power over the governmental structure and economic development of the Republic. In the Republic’s region of Antebellum Southern Appalachia this economic and governmental power over the region can be partly traced back to this class through the early land exchange. Origins of the Planter Economy: The Early Land Exchange The early exchange of Southern Appalachian lands was heavily dominated by wealthy Eastern speculators. One of the bigger reasons for this domination was the high prices of former Native American Appalachian land, and as a result "when land was marketed, [1] it was often too expensive for average Appalachians.” This resulted in a vast disparity of land ownership in the region which heavily favored speculators and left many without land. But this landlessness was not only due to high prices. Past land laws such as the Virginia Land Law of 1770 created confusion over land titles. As a result speculators utilized armies of lawyers to challenge land titles given to Revolutionary War veterans.[2] 2 Another tool utilized by speculators was the bribery of local officials, who controlled the sale of land in many cases, in order to get ownership of the region’s best lands.[3] These lands would be used for the creation of profits for further enrichment. One means of going about this was through the creation of towns; this process of creation would begin with the granting of permission to build such a town by the region's local government (which may have been done through bribery). -

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue PUBLIC ART SAINT PAUL: STEWARD OF SAINT PAUL’S CULTURAL TREASURES Art in Saint Paul’s public realm matters: it manifests Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) program 1993-94. and strengthens our affection for this city — the place This initiative of the Smithsonian Institution involved of our personal histories and civic lives. an inventory and basic condition assessment of works throughout America, carried out by trained The late 19th century witnessed a flourishing of volunteers whose reports were filed in a national new public sculptures in Saint Paul and in cities database. Cultural Historian Tom Zahn was engaged nationwide. These beautiful works, commissioned to manage this effort and has remained an advisor to from the great artists of the time by private our stewardship program ever since. individuals and by civic and fraternal organizations, spoke of civic values and celebrated heroes; they From the SOS! information, Public Art Saint illuminated history and presented transcendent Paul set out in 1993 to focus on two of the most allegory. At the time these gifts to states and cities artistically significant works in the city’s collection: were dedicated, little attention was paid to long Nathan Hale and the Indian Hunter and His Dog. term maintenance. Over time, weather, pollution, Art historian Mason Riddle researched the history vandalism, and neglect took a profound toll on these of the sculptures. We engaged the Upper Midwest cultural treasures. Conservation Association and its objects conservator Kristin Cheronis to examine and restore the Since 1994, Public Art Saint Paul has led the sculptures. -

African American Religious Leaders in the Late Antebellum South

Teaching Christianity in the face of adversity: African American religious leaders in the late antebellum South A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of English and American Studies PhD in the Faculty of Humanities 2011 Thomas Strange School of Arts, Histories, and Cultures Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Abbreviations 2 Abstract 3 Declaration 4 Copyright Statement 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: „For what God had done to their souls‟: the black preacher in the 19 colonial and early antebellum South Chapter 2: Preacher, teacher, counsellor or rebel: The multiple functions of 66 the black preacher on the plantation Chapter 3: The licensed black minister in the biracial and independent black 107 churches in the late antebellum South Chapter 4: The white evangelical reaction to African American religious 148 leaders and slave Christianity Conclusions 196 Appendix 204 Table 1: Statistics on WPA interviewee relocation 204 Table 2: Statistics on the location of black preachers in the WPA 205 narratives Bibliography 206 Word Count: 79,876 1 Abbreviations used Avery Avery Research Center, Charleston Caroliniana South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia Duke Duke University Special Collections, Durham ERO Essex Record Office, Chelmsford SHC Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill VHS Virginia Historical Society, Richmond VSL Virginia State Library, Richmond 2 Abstract Religious leaders were key figures within African American society in the late antebellum South. They undertook a vital religious function within both the plantation slave community and the institutionalised biracial and independent black church and many became a focal point for African American Christianity amongst slaves and free blacks. -

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston hilary j. moss N 7 May 1851, Thomas Paul Smith, a twenty-four-year- O old black Bostonian, closed the door of his used clothing shop and set out for home. His journey took him from the city’s center to its westerly edge, where tightly packed tene- ments pressed against the banks of the Charles River. As Smith strolled along Second Street, “some half-dozen” men grabbed, bound, and gagged him before he could cry out. They “beat and bruised” him and covered his mouth with a “plaster made of tar and other substances.” Before night’s end, Smith would be bat- tered so severely that, according to one witness, his antagonists must have wanted to kill him. Smith apparently reached the same conclusion. As the hands of the clock neared midnight, he broke free of his captors and sprinted down Second Street shouting “murder!”1 The author appreciates the generous insights of Jacqueline Jones, Jane Kamensky, James Brewer Stewart, Benjamin Irvin, Jeffrey Ferguson, David Wills, Jack Dougherty, Elizabeth Bouvier, J. M. Opal, Lindsay Silver, Emily Straus, Mitch Kachun, Robert Gross, Shane White, her colleagues in the departments of History and Black Studies at Amherst College, and the anonymous reviewers and editors of the NEQ. She is also grateful to Amherst College, Brandeis University, the Spencer Foundation, and the Rose and Irving Crown Family for financial support. 1Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Julian McCrea, Benjamin F. Roberts, and William J. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

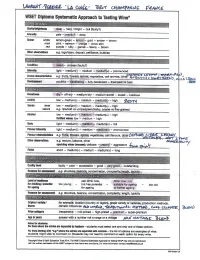

WSET Diploma Systematic Approach to Tasting Wine®

WSET Diploma Systematic Approach to Tasting Wine® EffRANGE Clarity/brightness ■ clear - hazy / bright - dull (faulty?) Intensity pale mediurfi - deep Colour wNte lemon-green - lemon - gold - amber - brown ros4 pink - salmon - orange - onion skin red purple - ruby - garnet - tawny - brown Other observations e.g. iegsAears, deposit, petillance, bubbles Condition clean i- unclean (faulty?) Intensity light - medium(-) - medium -> medium(+) - pronounced Aroma characteristics e.g. fruits, flowers, spices, vegetables, oak aromas,■ o t h e r S t S g . Development youthful - developing - fully developed - tired/past its best Sweetness dry - off-dry - medium-dry - medium-sweet - sweet - luscious Acidity low - medium(-) - medium - medium(-t) - high Tannin level low - medium(-) - medium - medium(+) - high nature e.g. ripe/soft vs unripe/green/stalky, coarse vs fine-grained Alcohol low - medium(-) - medium - medium(+) - high fortified wines: low - medium - high Body light - med[um(-) -.medium medium(+) - full Ravour intensity light - medium(-) - medium - m"edium(+) - pronounced Flavour characteristics e.g. fruits, fibwets, spices; vegetables, oak flavours, Other observations e.g. texture, balance, other sparkling wines (mousse): delicate - creamy - aggressive ,ry Rnish short - medium(-) - medium - medium(+) - long Quality level faulty - poor - acceptable - good - very good - outstanding Reasons for assessment e.g. structure, balance, concentration, complexity, lengtji, typicity« Level of readiness can drink now, drink now: not ■ for drinking/potential too young - but has potential suitable for ageing too old for ageing for ageing or further ageing Reasons for assessment e.g. structure, balance, concentration, complexity, length, typicity tiiWINE?iNfeOfiT;E» Origins/variety/ for example: location (country or region), grape variety or varieties, production methods, theme c l i m a t i c i n fl u e n c e s . -

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

American Exceptionalism and the Antebellum Slavery Debate Travis Cormier

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2014 American Exceptionalism And The Antebellum Slavery Debate Travis Cormier Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Cormier, Travis, "American Exceptionalism And The Antebellum Slavery Debate" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 1524. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1524 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM AND THE ANTEBELLUM SLAVERY DEBATE by Travis Cormier Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2014 This thesis, submitted by Travis Cormier in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved. _______________________________________ Eric Burin Date _______________________________________ James Mochoruk Date _______________________________________ Ty Reese Date This thesis is being submitted by the appointed -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

George Liele :Negro Slavery's Prophet of Deliverance

George Liele :Negro Slavery's Prophet of Deliverance EORGE LIELE (Lisle, Sharpe) is o:p.e of the unsung heroes of Greligious history, whose exploits and attainments have gone vir tually unnoticed except in a few little-known books and journals of Negro history. Liele's spectacular but steady devotion to the cause of his Master began with his conversion in 1773 and subsequent exercise of his ·cc call" in his own and nearby churches; it ended with mUltiple thousands of simple black folk raisec;I from the callous indignity of human bondage to freedom and a glorious citizenship in the king dom of God, largely as a consequence of this man's Christian witness in life and word. George was born a slave to slave parents, Liele and Nancy, in servitude to the family of Henry Sharpe in Virginia. From his birth, about 1750, to his eventual freedom in 1773, Liele belonged to the Sharpe family, with whom' he was removed to Burke County, Georgia, prior to 1770. Henry Sharpe, his master, was a Loyalist supporter and a deacon in the Buckhead Creek Baptist Church pastored by the Rev. Matthew Moore. Of his own parents and early years Liele reported in a letter of 1791 written from. Kingston, Jamaica: ~'I was born in Virginia, my father's name was Liele, and my mother's name Nancy; I cannot ascertain much of them, as I went to several parts of America when young, and at length resided in New Georgia; but was informed both by white and black people, that my father was the only black person who knew the Lord in a spiritual way in that country. -

Katie Grace 2 Page 1 of 3

Katie Grace 2 Page 1 of 3 1. Pastel Yellow-Green (Sul-R:1104) 2. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 3. Tawny Tan (Sul-R:1055) 4. Dk. Ecru (Sul-R:1128) 1. Pastel Yellow-Green (Sul-R:1104) 5. Pastel Mauve (Sul-R:1113) 2. Pastel Mauve (Sul-R:1113) 6. Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) 3. Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) 4. Silver (Sul-R:1085) 7. Silver (Sul-R:1085) 5. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 8. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 6. Taupe (Sul-R:1213) 9. Taupe (Sul-R:1213) 7. Dk. Ecru (Sul-R:1128) 10.Dk. Ecru (Sul-R:1128) 8. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 11.Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 9. Off White (Sul-R:1071) 12.Off White (Sul-R:1071) 10. Taupe (Sul-R:1213) 13.Taupe (Sul-R:1213) 11. Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) 14.Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) Gfe_kgr2_1.vp3 Gfe_kgr2_10.vp3 4.40x2.15 inches; 5,251 stitches 4.25x2.88 inches; 7,654 stitches 11 thread changes; 8 colors 14 thread changes; 9 colors 1. Pastel Yellow-Green (Sul-R:1104) 2. Pastel Mauve (Sul-R:1113) 3. Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) 1. Pastel Yellow-Green (Sul-R:1104) 2. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 4. Primrose (Sul-R:1066) 3. Tawny Tan (Sul-R:1055) 5. Butterfly Gold (Sul-R:567) 4. Dk. Ecru (Sul-R:1128) 5. Pastel Mauve (Sul-R:1113) 6. Silver (Sul-R:1085) 6. Lt. Putty (Sul-R:1229) 7. Ecru (Sul-R:1082) 7. Silver (Sul-R:1085) 8. Taupe (Sul-R:1213) 8.