The Rappahannock Indians of Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

A Re-Examination of the Omamori Phenomenon

The Hilltop Review Volume 7 Issue 2 Spring Article 19 April 2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: A Re-Examination of the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric (2015) "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: A Re-Examination of the Omamori Phenomenon," The Hilltop Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 19. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol7/iss2/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 152 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: A Re-Examination of the Omamori Phenomenon Runner-Up, 2013 Graduate Humanities Conference By Eric Teixeira Mendes Fireworks exploded, newspapers rushed “Extra!” editions into print and Japanese exchanged “Banzai!” cheers at news of Japan`s crown princess giving birth to a girl after more than eight years of marriage… In a forestate of the special life that awaits the baby, a purple sash and an imperial samurai sword were bestowed on the 6.8 pound girl just a few hours after her birth - - along with a sacred amulet said to ward off evil spirits. The girl will be named in a ceremony Friday, after experts are consulted on a proper name for the child. (Zielenziger) This quote, which ran on December 2, 2001, in an article from the Orlando Sentinel, describes the birth of one of Japan`s most recent princesses. -

Ocanahowan and Recently Discovered Linguistic

2 OCANAHOWAN AND RECENTLY DISCOVERED LINGUISTIC FRAGMENTS FROM SOUTHERN VIRGINIA, C. 1650 Philip Barbour Ridgefield, Connecticut Published in: Papers of the 7th Algonquian Conference (1975) Ocanahowan (or Ocanahonan and other spellings) was the name of an Indian town or village, region or tribe, which was first reported in Captain John Smith's True Relation in 1608 and vanished from the records after Smith mentioned it for the last time 1624, until it turned up again in a few handwritten lines in the back of a book. Briefly, these lines cover half a page of a small quarto, and have been ascribed to the period from about 1650 to perhaps the end of the century, on the basis of style of writing. The page in question is the blank verso of the last page in a copy of Robert Johnson's Nova Britannia, published in London in 1604, now in the possession of a distinguished bibliophile of Williamsburg, Virginia. When I first heard about it, I was in London doing research and brushing up on the English language, Easter-time 1974, and Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., got in touch with me about "some rather meaningless annotations" in a small volume they had for sale. Very briefly put, for I shall return to the matter in a few minutes, I saw that the notes were of the time of the Jamestown colony and that they contained a few Powhatan words. Now that the volume has a new owner, and I have his permission to xerox and talk about it, I can explain why it aroused my interest to such an extent. -

Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Teixeira Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric Teixeira, "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon" (2015). Master's Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/626 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON by Eric Teixeira Mendes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Religion Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Stephen Covell, Ph.D., Chair LouAnn Wurst, Ph.D. Brian C. Wilson, Ph.D. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON Eric Teixeira Mendes, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 This thesis offers an examination of modern Japanese amulets, called omamori, distributed by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. As amulets, these objects are meant to be carried by a person at all times in which they wish to receive the benefits that an omamori is said to offer. In modern times, in addition to being a religious object, these amulets have become accessories for cell-phones, bags, purses, and automobiles. -

Chapter 3 USFWS Great Spangled Fritillary

Chapter 3 USFWS Great spangled fritillary Existing Environment ■ Introduction ■ The Physical Landscape ■ The Cultural Landscape Setting and Land Use History ■ Current Climate ■ Air Quality ■ Water Quality ■ Regional Socio-Economic Setting ■ Refuge Administration ■ Special Use Permits, including Research ■ Refuge Natural Resources ■ Refuge Biological Resources ■ Refuge Visitor Services Program ■ Archealogical and Historical Resources The Physical Landscape Introduction This chapter describes the physical, biological, and social environment of the Rappahannock River Valley refuge. We provide descriptions of the physical landscape, the regional setting and its history, and the refuge setting, including its history, current administration, programs, and specifi c refuge resources. Much of what we describe below refl ects the refuge environment as it was in 2007. Since that time, we have been writing, compiling and reviewing this document. As such, some minor changes likely occurred to local conditions or refuge programs as we continued to implement under current management. However, we do not believe those changes appreciably affect what we present below. The Physical Landscape Watershed Our project area is part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, a drainage basin of 64,000 square miles encompassing parts of the states of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The waters of that basin fl ow into the Chesapeake Bay, the nation’s largest estuary. The watershed contains an array of habitat types, including mixed hardwood forests typical of the Appalachian Mountains, grasslands and agricultural fi elds, lakes, rivers, and streams, wetlands and shallow waters, and open water in tidal rivers and the estuary. That diversity supports more than 2,700 species of plants and animals, including Service trust resources such as endangered or threatened species, migratory birds, and anadromous fi sh (www.fws.gov/chesapeakebay/ coastpgm.htm). -

MIDDLE ATLANTIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE Rehoboth,Delaware Program

MIDDLE ATLANTIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE Rehoboth,Delaware Program If, I r. ..~ .' . and ~- .,. ,.1· ~ . -., ABSTRACTS - • ~, ~ ·1 i . • -1. l APRIL 2 - 4, 1982 National Museums and the R.eificati on of the Jacksonian Myth Ultj'l'O JUCAL AH.CHAEOLOGY AND THE David J . Meltzer CATEGORY OF THE IDEOTECHN IC Dept. of Anthropology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Symposi um or ganized for the 1982 Middle At l antic Archaeology Conference, Washington, D.C. 20560 Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. Schedul ed for Sunday morning, April 4 , 1982. Museums in general, and the gover nment-supported National Museums in Abstract for Symposium particular, are a curious blend of the empirical matter of history It has now been almost two decades since Lewis R. Binford (1962) in and the consc ious cr ea tio ~ of myth . As such, th ey are ideotechnic vented the category of ideotechnic artifacts : "items whic h signify ar tifa cts on a grand scale, and their operation reveals how Western and symbolize the ideologica l rationaliza t ions for the social system" ideolo gy is projected and enforced through the manipulation of ma and provide a symbolic milieu for everyday life . With the exception terial culture. Using as a focal point the museums within the of some Mayan interpretations no one has had great success in dis - Smithsonian Instituti on, this paper reflects on the reification of covering the ideotechnic amongs t the archaeological records of pre - the Ja cksonia n man, the expectant capitalist on the American frontier . modern societies . The papers tn thi s symposium explore this dilennna A brief historical account of the development of the Jacksonian through systematic examinations of id eotechnic artifacts in hist oric image is followed by an analysis of the manifestation of the myth and contemporary settings. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

The Making of an American Shinto Community

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SHINTO COMMUNITY By SARAH SPAID ISHIDA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2007 Sarah Spaid Ishida 2 To my brother, Travis 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people assisted in the production of this project. I would like to express my thanks to the many wonderful professors who I have learned from both at Wittenberg University and at the University of Florida, specifically the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Mario Poceski and Dr. Jason Neelis. For their time, advice and assistance, I would like to thank Dr. Travis Smith, Dr. Manuel Vásquez, Eleanor Finnegan, and Phillip Green. I would also like to thank Annie Newman for her continued help and efforts, David Hickey who assisted me in my research, and Paul Gomes III of the University of Hawai’i for volunteering his research to me. Additionally I want to thank all of my friends at the University of Florida and my husband, Kyohei, for their companionship, understanding, and late-night counseling. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to the Shinto community of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Reverend Koichi Barrish. Without them, this would not have been possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................7 -

Acts of the Eleventh Congress of the United States

ACTS OF THE ELEVENTH CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES, Passed at the first session, which was begun and held at the City of Washington, in the District of Columbia, on Monday, the twenty- second day of May, 1809, and ended on the twenty-eighth day of June, 1809. JAMES MADISON, President; GEORGE CLINTON, Vice President of the United States and President of the Senate; ANDREW GREGG, Pre- sident of the Senate pro tempore, on the 28th of June; J. B. VARNUM, Speaker of the House of Representatives. STATUTE I. CHAPTER I.--.n AcJt respecting the ships or vessels owned by citizens or subjects May 30, 1809. of foreign nations with which commercial intercourseis permitted. [Obsolete.] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United Act of March States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the 1,1809, ch. 24. Ships and ves- passing of this act, all ships or vessels owned by citizens or subjects of sels of foreign any foreign nation with which commercial intercourse is permitted by nations with the act, entituled "An act to interdict the commercial intercourse be- which inter- course is per- tween the United States and Great Britain and France, and their depen- mitted by the dencies, and for other purposes," be permitted to take on board cargoes act of March 1, of domestic or foreign produce, and to depart with the same for any 1809, shall be permitted to foreign port or place with which such intercourse is, or shall, at the take cargoes time of their departure respectively, be thus permitted, in the same man- and depart for ner, and on the same conditions, as is provided by the act aforesaid, for any port with which inter. -

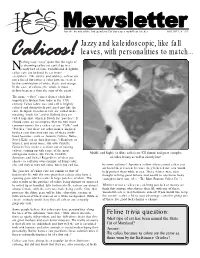

Jazzy and Kaleidoscopic, Like Fall Leaves, with Personalities to Match

For the friends of the Independent Cat Society, a no-kill cat shelter Fall 2011, # 134 Jazzy and kaleidoscopic, like fall leaves, with personalities to match... othing says “cozy” quite like the sight of a charming calico cat curled up in a Ncomfy ball of color. Colorful and delightful, calico cats are beloved by cat lovers everywhere. Like torties and tabbies, calicos are not a breed but rather a color pattern, created by the combination of white, black, and orange. In the case of calicos, the whole is most definitely greater than the sum of the parts! The name “calico” comes from a cloth first imported to Britain from India in the 17th century. Calico fabric was and still is brightly colored and distinctively patterned just like the cats. In Japan, tri-colored cats are called mi-ke, meaning “triple fur,” and in Holland they are called lapjeskat, which is Dutch for “patches.” It should come as no surprise that the two most common names for a calico cat are “Callie” and “Patches,” but there are other names inspired by their coat that may suit one of these multi- hued beauties, such as Autumn, Calista, Dottie, Jewel, Kalie (as in “kaleidoscope,”) Rainbow, or Sunset, and many more. Our own Paulette Gonzalez has made a science out of naming calicos, coming up with some of the most outrageous names, like Fiesta, Confetti, Maddie and Sophie (a dilute calico) are ICS alumni, and great examples Spumoni, and Salsa! Regardless of what you of calico beauty, as well as sisterly love! choose to call your own example of living color, she still may or may not come when you call her. -

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Crandall A. Shifflett, Chair A. Roger Ekirch Brett L. Shadle 16 March 2010 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Early Modern England; Colonial Virginia; Jamestown; Devil; Fear Copyright 2010, Matthew John Sparacio The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio ABSTRACT This study examines the role of emotions – specifically fear – in the development and early stages of settlement at Jamestown. More so than any other factor, the Protestant belief system transplanted by the first settlers to Virginia helps explain the hardships the English encountered in the New World, as well as influencing English perceptions of self and other. Out of this transplanted Protestantism emerged a discourse of fear that revolved around the agency of the Devil in the temporal world. Reformed beliefs of the Devil identified domestic English Catholics and English imperial rivals from Iberia as agents of the diabolical. These fears travelled to Virginia, where the English quickly ʻsatanizedʼ another group, the Virginia Algonquians, based upon misperceptions of native religious and cultural practices. I argue that English belief in the diabolic nature of the Native Americans played a significant role during the “starving time” winter of 1609-1610. In addition to the acknowledged agency of the Devil, Reformed belief recognized the existence of providential actions based upon continued adherence to the Englishʼs nationally perceived covenant with the Almighty.