North Sea Oil and Gas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Oil and Gas Challenges

Order Code RL33212 Russian Oil and Gas Challenges Updated June 20, 2007 Robert Pirog Specialist in Energy Economics and Policy Resources, Science, and Industry Division Russian Oil and Gas Challenges Summary Russia is a major player in world energy markets. It has more proven natural gas reserves than any other country, is among the top ten in proven oil reserves, is the largest exporter of natural gas, the second largest oil exporter, and the third largest energy consumer. Energy exports have been a major driver of Russia’s economic growth over the last five years, as Russian oil production has risen strongly and world oil prices have been very high. This type of growth has made the Russian economy dependent on oil and natural gas exports and vulnerable to fluctuations in oil prices. The Russian government has moved to take control of the country’s energy supplies. It broke up the previously large energy company Yukos and acquired its main oil production subsidiary. The Duma voted to give Gazprom, the state- controlled natural gas monopoly the exclusive right to export natural gas; Russia moved to limit participation by foreign companies in oil and gas production and Gazprom gained majority control of the Sakhalin energy projects. Russia has agreed with Germany to supply Germany and, eventually, the UK by building a natural gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea, bypassing Ukraine and Poland. In late 2006 and early 2007, Russia cut off and/or threatened to cut off gas or oil supplies going to and/or through Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Belarus in the context of price and/or transit negotiations — actions that damaged its reputation as a reliable energy supplier. -

Enquest Announces the Appointment of Neil Mcculloch As Head of Its North Sea Business

ENQUEST ANNOUNCES THE APPOINTMENT OF NEIL MCCULLOCH AS HEAD OF ITS NORTH SEA BUSINESS EnQuest PLC is pleased to announce the appointment of Neil McCulloch as President, North Sea, with effect from 1 April 2014. Neil has held a number of senior positions in the oil and gas sector, and joins EnQuest from international oil and gas company OMV AG, where he held the global role of Senior Vice President Production & Engineering. Prior to this, Neil spent 11 years with BG Group in a range of senior UK and international roles, most recently as Vice President & Asset General Manager, UK Upstream, with accountability for the delivery of BG’s UK North Sea business. Neil will succeed David Heslop, who retires from his role as Managing Director UKCS on 1 April 2014. Thereafter David will continue to support EnQuest in an advisory capacity or on special projects. Amjad Bseisu, Chief Executive of EnQuest said: “I am delighted to welcome Neil as head of our North Sea business. With his wealth of technical and management experience in the oil and gas industry and in the UK North Sea in particular, I am confident that Neil will be an excellent member of EnQuest’s senior management team and will make a valuable contribution to the growth and development of EnQuest over the coming years. “The Board and I would also like to express our sincere gratitude to David for his contribution to EnQuest in our formative years; his leadership, knowledge and experience have been key to many of EnQuest’s successes and achievements, and have helped us to build a world class organisation in Aberdeen. -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

Guide to the American Petroleum Institute Photograph and Film Collection, 1860S-1980S

Guide to the American Petroleum Institute Photograph and Film Collection, 1860s-1980s NMAH.AC.0711 Bob Ageton (volunteer) and Kelly Gaberlavage (intern), August 2004 and May 2006; supervised by Alison L. Oswald, archivist. August 2004 and May 2006 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Historical Photographs, 1850s-1950s....................................................... 6 Series 2: Modern Photographs, 1960s-1980s........................................................ 75 Series 3: Miscellaneous -

Offshore Wind Operations & Maintenance a £9 Billion Per

OFFSHORE WIND OPERATIONS & MAINTENANCE A £9 BILLION PER YEAR OPPORTUNITY BY 2O3O FOR THE UK TO SEIZE OPERATIONS & MAINTENANCE SUMMARY New data compiled by the Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult reveals the UK offshore wind operations & maintenance (O&M) market will grow faster in relative terms than any other offshore wind sub sector market over the next decade. By 2O3O, it will be the UK’s second largest sub sector market after turbine supply: a projected £1.3 billion per year opportunity. The Rest of the World (excluding UK) offshore wind O&M market opportunity is even greater. We project it will be valued at £7.6 billion per year by 2030. To discuss commercial dynamics in offshore wind O&M, we conducted an interview with energy industry leader Sir Ian Wood, which is summarised below. His comments highlight that offshore wind O&M is an area that plays to the UK’s existing strengths in offshore oil and gas services and associated technologies. O&M already has the highest level of UK content of any part of the offshore wind supply chain. In short, there is a sizable opportunity for the UK to create internationally significant service businesses in offshore wind O&M, learning from experience from the North Sea oil and gas industry. We already have the vital elements to capture this opportunity but investment in infrastructure to create the environment for collaborative development and demonstration of the enabling technologies and services is required. DEFINING OFFSHORE WIND O&M A clear definition of offshore wind O&M comes from a report published by GL Garrad Hassan: Offshore wind O&M is the activity that follows commissioning to ensure the safe and economic running of the project. -

Prospective Decommissioning Activity and Infrastructure Availability in the UKCS

NORTH SEA STUDY OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 122 Prospective Decommissioning Activity and Infrastructure Availability in the UKCS Professor Alexander G. Kemp and Linda Stephen October, 2011 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS ISSN 0143-022X NORTH SEA ECONOMICS Research in North Sea Economics has been conducted in the Economics Department since 1973. The present and likely future effects of oil and gas developments on the Scottish economy formed the subject of a long term study undertaken for the Scottish Office. The final report of this study, The Economic Impact of North Sea Oil on Scotland, was published by HMSO in 1978. In more recent years further work has been done on the impact of oil on local economies and on the barriers to entry and characteristics of the supply companies in the offshore oil industry. The second and longer lasting theme of research has been an analysis of licensing and fiscal regimes applied to petroleum exploitation. Work in this field was initially financed by a major firm of accountants, by British Petroleum, and subsequently by the Shell Grants Committee. Much of this work has involved analysis of fiscal systems in other oil producing countries including Australia, Canada, the United States, Indonesia, Egypt, Nigeria and Malaysia. Because of the continuing interest in the UK fiscal system many papers have been produced on the effects of this regime. From 1985 to 1987 the Economic and Social Science Research Council financed research on the relationship between oil companies and Governments in the UK, Norway, Denmark and The Netherlands. A main part of this work involved the construction of Monte Carlo simulation models which have been employed to measure the extents to which fiscal systems share in exploration and development risks. -

Mipeg User Reference List

Aanderaa Data Instruments Document Y-101 D00 160 Page 1 of 9 Date 01.05.2013 MIPEG SYSTEMS USER REFERENCE LIST MIPEG Systems have been extensively installed on a wide variety of cranes. Systems are operating offshore in all parts of the world. The systems are used on fixed platforms, drilling rigs, pipe laying barges, lift boats, FPSO`s and drill ships. Units have also been fitted to high integrity overhead travelling cranes in the Nuclear Electricity Generating Field, cranes operated by Ministry of Defence (UK), Corps of Engineers (USA) and US Navy The current 'family' of MIPEG Systems comprises: MIPEG 2000R - Load/Moment Dynamic Monitoring and Recording System MIPEG 2000NR - Automatic Safe Load Indicator MIPEG RSI - Rope Speed/Direction Indicating Device MIPEG OLM - Operating Limits Monitor To date, more than 2173 MIPEG Systems have been delivered by Aanderaa Data Instruments A.S. Details of the operators and locations of the MIPEG Systems are listed below. OPERATORS : ACT, AES OTTO INDUSTRIES, ADMA OPCO, AIOC, AGIP, AMERADA HESS, APACHE ENERGY, ARABIAN DRILLING, ATLANTIC DRILLING, ATP O&G, ATWOOD OCEANICS, AWILCO, BASS DRILL, BETA DRILLING, BHP,BIBBY OFFSHORE, BRITISH GAS, BP , BP VESTAR, BW OFFSHORE, CACT, CENTRICA, CNR-CANADIAN NATIONAL RESOURCES, CHEVRON-TEXACO, CLEARWAYS DRILLING, CLOUGH, CLYDE PETROLEUM, CONSAFE, COSDC, CNOOC, CONOCO-PHILLIPS, CORPS OF ENGINEERS, CPOE, DANOS&CUROLE, DEVON ENERGY, DIAMOND OFFSHORE, DOLPHIN DRILLING, DOMINION EXPL. DYNEGY, DYVI OFFSHORE, E-ON, ENCANA, EL PASO ENERGY, ENSCO, ENTERPRISE OIL, ENSERCH, ETESCO, EXMAR OFFSHORE, EXXONMOBIL, EZRA MARINE, FLUOR DANIEL, FRONTIER DRILLING, GAS de FRANCE, GLOMAR INTERNATIONAL, GSP UPETROM, GULF OFFSHORE, GUPCO, GUSTO, HELMERICH & PAYNE, HYDROCARBON RESOURCES, I.P.C, IRAN MARINE, J. -

Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System

Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System As submitted to the European Commission in April 2012 following the first stage of their scrutiny process This document has been issued by the Department of Energy and Climate Change, together with the Devolved Administrations for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. April 2012 UK’s National Implementation Measures submission – April 2012 Modified UK National Implementation Measures for Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System As submitted to the European Commission in April 2012 following the first stage of their scrutiny process On 12 December 2011, the UK submitted to the European Commission the UK’s National Implementation Measures (NIMs), containing the preliminary levels of free allocation of allowances to installations under Phase III of the EU Emissions Trading System (2013-2020), in accordance with Article 11 of the revised ETS Directive (2009/29/EC). In response to queries raised by the European Commission during the first stage of their assessment of the UK’s NIMs, the UK has made a small number of modifications to its NIMs. This includes the introduction of preliminary levels of free allocation for four additional installations and amendments to the preliminary free allocation levels of seven installations that were included in the original NIMs submission. The operators of the installations affected have been informed directly of these changes. The allocations are not final at this stage as the Commission’s NIMs scrutiny process is ongoing. Only when all installation-level allocations for an EU Member State have been approved will that Member State’s NIMs and the preliminary levels of allocation be accepted. -

List of Shetland Islands' Contributors Being Sought by Kist O Riches

List of Shetland Islands’ Contributors being Sought by Kist o Riches If you have information about any of the people listed or their next-of-kin, please e-mail Fraser McRobert at [email protected] or call him on 01471 888603. Many thanks! Information about Contributors Year Recorded 1. Mrs Robertson from Burravoe in Yell who was recorded reciting riddles. She was recorded along with John 1954 Robertson, who may have been her husband. 2. John Robertson from Fetlar whose nickname was 'Jackson' as he always used to play the tune 'Jackson's Jig'. 1959 He had a wife called Annie and a daughter, Aileen, who married one of the Hughsons from Fetlar. 3. Mr Gray who sounded quite elderly at the time of recording. He talks about fiddle tunes and gives information 1960 about weddings. He may be the father of Gibbie Gray 4. Mr Halcro who was recorded in Sandwick. He has a local accent and tells a local story about Cumlewick 1960 5. Peggy Johnson, who is singing the ‘Fetlar Cradle Song’ in one of her recordings. 1960 6. Willie Pottinger, who was a fiddle player. 1960 7. James Stenness from the Shetland Mainland. He was born in 1880 and worked as a beach boy in Stenness in 1960 1895. Although Stenness is given as his surname it may be his place of origin 8. Trying to trace all members of the Shetland Folk Club Traditional Band. All of them were fiddlers apart from 1960 Billy Kay on piano. Members already identified are Tom Anderson, Willie Hunter Snr, Peter Fraser, Larry Peterson and Willie Anderson 9. -

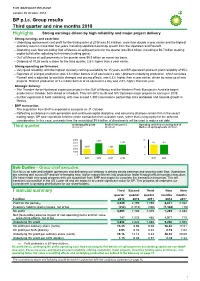

BP P.L.C. Group Results Third Quarter and Nine Months 2018 Highlights Third Quarter Financial Summary

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE London 30 October 2018 BP p.l.c. Group results Third quarter and nine months 2018 Highlights Strong earnings driven by high reliability and major project delivery • Strong earnings and cash flow: – Underlying replacement cost profit for the third quarter of 2018 was $3.8 billion, more than double a year earlier and the highest quarterly result in more than five years, including significant earnings growth from the Upstream and Rosneft. – Operating cash flow excluding Gulf of Mexico oil spill payments for the quarter was $6.6 billion, including a $0.7 billion working capital build (after adjusting for inventory holding gains). – Gulf of Mexico oil spill payments in the quarter were $0.5 billion on a post-tax basis. – Dividend of 10.25 cents a share for the third quarter, 2.5% higher than a year earlier. • Strong operating performance: – Very good reliability, with the highest quarterly refining availability for 15 years and BP-operated Upstream plant reliability of 95%. – Reported oil and gas production was 3.6 million barrels of oil equivalent a day. Upstream underlying production, which excludes Rosneft and is adjusted for portfolio changes and pricing effects, was 6.8% higher than a year earlier, driven by ramp-up of new projects. Rosneft production of 1.2 million barrels of oil equivalent a day was 2.8% higher than last year. • Strategic delivery: – The Thunder Horse Northwest expansion project in the Gulf of Mexico and the Western Flank B project in Australia began production in October, both ahead of schedule. They are BP’s fourth and fifth Upstream major projects to start up in 2018. -

NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENTN=== of ENERGY Nova Scotia EXPORT MARKET ANALYSIS

NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENTN=== OF ENERGY Nova Scotia EXPORT MARKET ANALYSIS MARCH 2017 Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Best Prospects Charts…….………………………………………………………………………………….…...……………………………………..6 Angola Country Profile .................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Australia Country Profile ................................................................................................................................................................. 19 Brazil Country Profile ....................................................................................................................................................................... 30 Canada Country Profile ................................................................................................................................................................... 39 China Country Profile ....................................................................................................................................................................... 57 Denmark Country Profile ................................................................................................................................................................ 67 Kazakhstan Country Profile .......................................................................................................................................................... -

SPE Review London, January 2018

Issue 27 \ January 2018 LONDON • FPS Pipeline System: a brief history • Are Oil Producers Misguided? PLUS: events, jobs and more NEWS Contents Information ADMINISTRATIVE Welcome to 2018! At SPE Review London, we strive to provide knowledge and Behind the Scenes ...3 information to navigate our changing, and challenging, industry. We trust the January 2018 issue of SPE Review London will be SPE London: Meet the Board ...9 useful, actionable and informative. In the first of two technical features in this issue, ‘FPS Pipeline System: a brief historical overview’, Jonathan Ovens, Senior TECHNICAL FEATURES Reservoir Engineer at JX Nippon E&P (UK) Ltd., provides (page 4) a FPS Pipeline System: a brief timely overview of this key piece of North Sea infrastructure. historical overview ...4 The second of this issue’s technical features starts on page 6, and Oil and gas production from the North Sea poses the question: Are Oil Producers Misguided? Based on a wide- relies on existing infrastructure that, overall, ranging lecture given in January at SPE London by Iskander Diyashev, is highly reliable but rarely mentioned. it discusses the potential future of the oil industry, electric cars, How much do you know about it? nuclear and solar energy. Are Oil Producers Misguided? ...6 Our regular features include: Meet the people ‘behind the scenes’: Are there lessons to be learned as we The SPE Review Editorial Board (page 3), the SPE London Board transition into a new era where the (page 9), and make sure to keep up to date with industry events fundamental value of energy will be and networking opportunities,and the Job Board, all on Page 11.