Reading Gestures in Valentin De Boulogne's Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D

The Virtuoso of Compassion Ingrid D. Rowland MAY 11, 2017 ISSUE The Guardian of Mercy: How an Extraordinary Painting by Caravaggio Changed an Ordinary Life Today by Terence Ward Arcade, 183 pp., $24.99 Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 7, 2016–January 22, 2017; and the Musée du Louvre, Paris, February 20–May 22, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Annick Lemoine and Keith Christiansen Metropolitan Museum of Art, 276 pp., $65.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) Beyond Caravaggio an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, October 12, 2016–January 15, 2017; the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, February 11–May 14, 2017 Catalog of the exhibition by Letizia Treves and others London: National Gallery, 208 pp., $40.00 (distributed by Yale University Press) The Seven Acts of Mercy a play by Anders Lustgarten, produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon- Avon, November 24, 2016–February 10, 2017 Caravaggio: The Seven Acts of Mercy, 1607 Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples Two museums, London’s National Gallery and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, mounted exhibitions in the fall of 2016 with the title “Beyond Caravaggio,” proof that the foul-tempered, short-lived Milanese painter (1571–1610) still has us in his thrall. The New York show, “Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio,” concentrated its attention on the French immigrant to Rome who became one of Caravaggio’s most important artistic successors. The National Gallery, for its part, ventured “beyond Caravaggio” with a choice display of Baroque paintings from the National Galleries of London, Dublin, and Edinburgh as well as other collections, many of them taken to be works by Caravaggio when they were first imported from Italy. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

The Representation of Roma in Major European Museum Collections

The Council of Europe is a key player in the fight to respect THE REPRESENTATION OF ROMA the rights and equal treatment of Roma and Travellers. As such, it implements various actions aimed at combating IN MAJOR EUROPEAN discrimination: facilitating the access of Roma and Travellers to public services and justice; giving visibility to their history, MUSEUM COLLECTIONS culture and languages; and ensuring their participation in the different levels of decision making. Another aspect of the Council of Europe’s work is to improve the wider public’s understanding of the Roma and their place in Europe. Knowing and understanding Roma and Travellers, their customs, their professions, their history, their migration and the laws affecting them are indispensable elements for interpreting the situation of Roma and Travellers today and understanding the discrimination they face. This publication focuses on what the works exhibited at the Louvre Museum tell us about the place and perception of Roma in Europe from the15th to the 19th centuries. Students aged 12 to 18, teachers, and any other visitor to the Louvre interested in this theme, will find detailed worksheets on 15 paintings representing Roma and Travellers and a booklet to foster reflection on the works and their context, while creating links with our contemporary perception of Roma and Travellers in today’s society. 05320 0 PREMS ENG The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights organisation. It comprises 47 member Volume I – The Louvre states, including all members of the European Union. Sarah Carmona All Council of Europe member states have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law. -

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 p.m. - 5 p.m. 2nd Fridays 10 a.m. – 9 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. -

Baroque Women: Pictures of Purity and Debauchery

Baroque Women: Pictures of Purity and Debauchery By: Analise Austin, Mentor: Dr. Niria Leyva-Gutierrez Arts Management College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Abstract Throughout the Baroque period, and much of the world’s artistic history, women have been portrayed as either saints or sinners, pictures of purity or wicked temptresses. Women have known little middle ground historically, despite occupying diverse roles and representing half the world’s population. In Catholic nations, where most art was religious in nature, Baroque women met the dichotomy of being cast as either saint or sinner, mother or virgin. Whether tender images of Mary as a doting mother, saints tending to wounded souls, or virgins pure in body and spirit, the image of a good woman was docile, kind and soft. If not soft and docile, women were depicted as whores, adulteresses and tricksters, wicked temptations to good men. There was little in between for Catholic representation of the woman at this time. In the northern, protestant states however, alternate depictions of women began to emerge in the growing prominence of genre painting. It is here women were attributed with a slightly greater range of characters, perhaps a housewife, young bride, or an elderly matron. While not restrained to mere saint or sinner, women were still chained to their relation to the men around them. Their depicted identities remained flat in the accepted social roles of their gender and were rarely see outside of a domestic sphere. Whether religious or genre, women were nearly always represented in terms of their value or relation to men. -

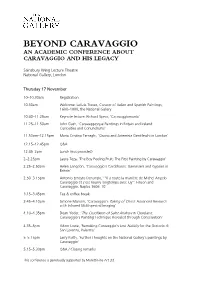

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics the Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet

Nuncius 31 (2016) 288–331 brill.com/nun The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics The Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet Susana Gómez López* Faculty of Philosophy, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract In his excellent work Anamorphoses ou perspectives curieuses (1955), Baltrusaitis con- cluded the chapter on catoptric anamorphosis with an allusion to the small engraving by Hans Tröschel (1585–1628) after Simon Vouet’s drawing Eight satyrs observing an ele- phantreflectedonacylinder, the first known representation of a cylindrical anamorpho- sis made in Europe. This paper explores the Baroque intellectual and artistic context in which Vouet made his drawing, attempting to answer two central sets of questions. Firstly, why did Vouet make this image? For what purpose did he ideate such a curi- ous image? Was it commissioned or did Vouet intend to offer it to someone? And if so, to whom? A reconstruction of this story leads me to conclude that the cylindrical anamorphosis was conceived as an emblem for Prince Maurice of Savoy. Secondly, how did what was originally the project for a sophisticated emblem give rise in Paris, after the return of Vouet from Italy in 1627, to the geometrical study of catoptrical anamor- phosis? Through the study of this case, I hope to show that in early modern science the emblematic tradition was not only linked to natural history, but that insofar as it was a central feature of Baroque culture, it seeped into other branches of scientific inquiry, in this case the development of catoptrical anamorphosis. Vouet’s image is also a good example of how the visual and artistic poetics of the baroque were closely linked – to the point of being inseparable – with the scientific developments of the period. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia Cár - Pozri Jurodiví/Blázni V Kristu; Rusko

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia cár - pozri jurodiví/blázni v Kristu; Rusko Georges Becker: Korunovácia cára Alexandra III. a cisárovnej Márie Fjodorovny Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 1 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia N. Nevrev: Roman Veľký prijíma veľvyslanca pápeža Innocenta III (1875) Cár kolokol - Expres: zvon z počiatku 17.st. odliaty na príkaz cára Borisa Godunova (1552-1605); mal 36 ton; bol zavesený v štvormetrovej výške a rozhojdávalo ho 12 ľudí; počas jedného z požiarov spadol a rozbil sa; roku 1654 z jeho ostatkov odlial ruský majster Danilo Danilov ešte väčší zvon; o rok neskoršie zvon praskol úderom srdca; ďalší nasledovník Cára kolokola bol odliaty v Kremli; 24 rokov videl na provizórnej konštrukcii; napokon sa našiel majster, ktorému trvalo deväť mesiacov, kým ho zdvihol na Uspenský chrám; tam zotrval do požiaru roku 1701, keď spadol a rozbil sa; dnešný Cár kolokol bol formovaný v roku 1734, ale odliaty až o rok neskoršie; plnenie formy kovom trvalo hodinu a štvrť a tavba trvala 36 hodín; keď roku 1737 vypukol v Moskve požiar, praskol zvon pri nerovnomernom ochladzovaní studenou vodou; trhliny sa rozšírili po mnohých miestach a jedna časť sa dokonca oddelila; iba tento úlomok váži 11,5 tony; celý zvon váži viac ako 200 ton a má výšku 6m 14cm; priemer v najširšej časti je 6,6m; v jeho materiáli sa okrem klasickej zvonoviny našli aj podiely zlata a striebra; viac ako 100 rokov ostal zvon v jame, v ktorej ho odliali; pred rokom 2000 poverili monumentalistu Zuraba Cereteliho odliatím nového Cára kolokola, ktorý mal odbiť vstup do nového milénia; myšlienka však nebola doteraz zrealizovaná Caracallove kúpele - pozri Rím http://referaty.atlas.sk/vseobecne-humanitne/kultura-a-umenie/48731/caracallove-kupele Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 2 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia G. -

Art Tells a Story Fortune Teller with Soldiers

Art Tells a Story Fortune Teller with Soldiers Teacher Resource: Grades 6–8 Fortune Teller with Soldiers (detail), Valentin de Boulogne 1981.53 This resource will allow you to lead your students through close looking exercises to enable them to describe, analyze and interpret what they see in the painting Fortune Teller with Soldiers (about 1620) by Valentin de Boulogne (French, 1591–1632). This approach to looking at art is based on the Art of Seeing Art method created by the Toledo Museum of Art. It is worksheet-based and will help you and your students explore French works of art in the Toledo Museum of Art’s collection. How to use this resource: • Print out the document for yourself. • Read through the document carefully as you look at the image of the work of art. • When you are ready to engage your class, project the image of the work of art on a screen in your classroom using an LCD projector. • In small groups have the students work together to complete the attached Art of Seeing Art worksheet. This exercise is meant for use in the classroom. There is no substitute for seeing the real work of art in the exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art. We are open: Tuesday and Wednesday 10 AM–4 PM Thursday and Friday 10 AM–9 PM Saturday 10 AM–5 PM Sunday 12 PM–5 PM Docent-led tours are available free of charge. Visit http://www.toledomuseum.org/visit/tours/school- tours/ to schedule. Connections to the Common Core State Standards and Ohio’s New Learning Standards: The Common Core State Standards were designed to help teachers provide knowledge and foster skills in students that are necessary in order for them to successfully navigate the contemporary world. -

Caravaggio and His Influence

Caravaggio and His Influence at West House, Saturday, 17th September 2016, 9.45am to 2.30pm Caravaggio: Gypsy Fortune Teller, 1596-97; Musee Du Louvre See: http://tinyurl.com/jc8zqn9 CARAVAGGIO AND HIS INFLUENCE Brutal realism and dramatic contrasts of light and shade mark the style of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573-1610) whose influence swept across Western Europe in the first half of the seventeenth century. At one extreme his religious paintings can reveal a powerful spirituality aimed at the ordinary man in the street, while his paintings of cardsharpers, fortune-tellers etc and those of his followers vividly portray the more squalid side of daily life. We first consider Caravaggio’s own career and next his influence in Italy, Spain, Holland and France. Lists of slides shown will be provided. TUTOR Leslie Pitcher (B.A. Cantab.) has a degree in Classical Literature and Languages at Trinity College, Cambridge. He lectures for NADFAS, WEA, and U3A. He has also lectured at Brompton Oratory on Religious Art. His particular interest is in the Classical tradition in art from the ancient world to the Renaissance. PROGRAMME 9.45 Doors open 10.00 Caravaggio in Rome: Caravaggio’s career in Rome – his ‘low life’ scenes (with powerful lighting and still-life details) and a detailed look at the “Calling of St Matthew”, which unforgettably mixes a Biblical subject with contemporary life. 11.00 Coffee/tea 11.30 Caravaggio’s later work and influence in Italy and Spain: Caravaggio’s later, sombre paintings in Naples and Malta. His influence in Italy on the Gentileschi and in Spain on Ribera and the early Velasquez. -

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 MASTERPIECES OF EUROPEAN PAINTING FROM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART November 8, 2006, through January 28, 2007 The Frick Collection is pleased to present an exhibition of fourteen extraordinary paintings from The Cleveland Museum of Art from November 8, 2006, through January 28, 2007. This exciting opportunity is a result of the major expansion and renovation project currently underway at the famed Cleveland, Ohio, institution, where ground-breaking last autumn was followed by a temporary gallery closure between January and fall 2006. The exhibition in the Frick’s Oval Room and Garden Court features paintings by Fra Filippo Lippi (1406– 1469), Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530), El Greco (1541–1614), Annibale Carracci (c. 1560–1609), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573–1610), Frans Hals Andrea del Sarto, The Sacrifice of Isaac, c. 1527, Oil (c. 1581–1666), Georges de La Tour (1593–1652), Valentin de Boulogne on poplar, Framed: 208 x 171 x 12.5 cm, Unframed: 178 x 138 cm (70 1/8 x 54 5/16 in.), The Cleveland (1591?–1632), Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), Francisco de Zurbarán (1598– Museum of Art, Delia E. Holden and L. E. Holden Funds 1664), Diego de Velázquez (1599–1660), Jacques Louis David (1748–1825), and J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851). The installation is organized by Colin B. Bailey, Chief Curator of The Frick Collection, with the assistance of Margaret Iacono, Assistant Curator, in collaboration with The Cleveland Museum of Art. -

Seventeenth-Century Italian Painting

Seventeenth-century Italian Painting ... The seventeenth century offers a surprising diversity of expression due to the specificity of the nations making up Europe, as well as the succession of political and cultural events that would drastically change ideas that had endured from generation to generation. The Italian works here testify to this proliferation, from the final hours of Mannerism (Cigoli) to the twofold dominant influence of Caravaggio’s realism (Preti, Ribera…) and Bolognese classicism (Domenichino, Cagnacci…). In the face of Italian models, French painting asserted its otherness with key artists such as Poussin or Vouet, as well as Bourdon, Stella, Blanchard or La Hyre who offered an infinite variety of trends (including classicism, Italianism and atticism). The Griffin Gallery Caravaggio, the Carracci ... and the Emergence of Baroque European Art In the seventeenth century only the Church States and the Serenissima “Most Serene” from the Fourteenth to Republic of Venice retained relative autonomy in an Italy controlled by foreign powers. Since Eighteenth Century the sack of Rome in 1527, Milan, the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily had been under Spanish domination. The grand duchy of Tuscany received Iberian garrisons and the Republic of Genoa accommodated the invincible Armada. Independent duchies such as Mantua-Montferrat, Parma- Plaisance and Modena-Reggio were under French supervision. Yet the Italian peninsula continued to pursue its cultural influence, and the richness of its various regional centres ... provided a real artistic proliferation. At the turn of the century, there were two dominant tendencies : in Bologna, followed by Rome, the Carracci formed a movement styled on classicism, while from Genoa to Naples Caravaggio introduced tenebrism and realism.