Tree Rings the Journal of the Yuba Watershed Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 30, 2020

Valley air about to get worse as wildfire smoke has nowhere to go By Corin Hoggard and Dale Yurong Tuesday, September 29, 2020 FRESNO, Calif. (KFSN) -- Air quality is about to take a turn for the worse as a changing weather pattern will combine with wildfires to fill the Central Valley with smoke again. The last few months have produced a stretch of the worst air quality on record, according to the Air Pollution Control District. Satellite images show smoke gently blowing from several California fires out to the Pacific Ocean, a weather pattern keeping the Valley's air relatively clean for several days now. "Right now we're seeing the smoke aloft," said Maricela Velasquez of the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District. "It's above us. But as the week goes through, we'll continue to see that smoke come onto the Valley floor." Here's how: When you have a fire in the Central Valley -- which is essentially just a bowl -- the smoke can usually get out and air quality won't be bad everywhere. But when a high pressure system comes in, it essentially puts a lid on the bowl and the smoke has nowhere to go so it just collects on the Valley floor. "The blocking high, basically, once it sits over a certain spot it likes to stay there for quite a while," said meteorologist Carlos Molina of the National Weather Service in Hanford. Forecasters at the NWS say the lid will sit on our bowl for at least a week. Air Quality Science Director Jon Klassen of the Valley Air District said, "We're expecting that to continue in the coming days." By that time, our air will have collected smoke from the Creek Fire, the SQF Complex Fire, and even more recent fires to our west, like the Glass Fire in the Bay Area. -

Loyalton Resource Supply Assess Report Final Redacted 20210204

BIOMASS FUEL AND LOG SUPPLY AVAILABILITY AND COST ASSESSMENT FOR A BIOMASS POWER FACILITY AND SAWMILL COLLOCATED AT LOYALTON, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Prepared by: February 4, 2021 Final Report REDACTED VERSION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TSS Consultants wishes to thank individuals and organizations for their significant efforts in support of this investigation. These include, but are not limited to: • Amy Berry, Chief Executive Officer, Tahoe Fund • John B. Jones, Jr., Board Member, Tahoe Fund • Jim Boyd, Board Member, Tahoe Fund • Jim Turner, Chief Operations Officer, Sierra Valley Enterprises • Jon Shinn, Forest Products Manufacturing Consultant • Steve Frisch, President, Sierra Business Council USFS Vegetation Management, Contracting and Biomass Utilization Staff: o Larry Swan, Regional Office o Tim Howard, Regional Office o Dan Smith, Eldorado National Forest o Brian Garrett, Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit o Victor Lyon, Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit o David Fournier, Tahoe National Forest o Annabelle Monti, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest o Will Brendecke, Plumas National Forest • Coreen Francis, State Forester, California and Nevada, Bureau of Land Management • Mike Vollmer, Forester, Nevada Division of Forestry • Steve Brink, Vice President, California Forestry Association • Bob Rynearson, Forester, W.M. Beaty and Associations • Mike Mitsel, Forester, Sierra Pacific Industries • Dan Porter, The Nature Conservancy • Craig Thomas, The Fire Restoration Group • Niel Fischer, Forest Manager, Collins Pine Company • Nic Enstice, Sierra Nevada -

Planning, Funding, and Implementing Fuels Reduction and Wildfire Education in Butte County

Planning, Funding, and Implementing Fuels Reduction and Wildfire Education in Butte County Special Report on the North Complex Wildfire By Butte County Fire Safe Council 10/7/2020 Contents 1. Problem Statement - Wildfire in Butte County – a 20-Year Snapshot - How Much Funding Has Been Utilized? - How Many Projects are Listed? - What is the Future of Funding? a. Why is CEQA a Challenge? Examples of Challenges b. How Can CEQA Be Streamlined for Fuels Reduction in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI)? 2. Examples – Challenges in implementing Fuels Reduction 3. Supporting Information Appendix 1) Large fires within Butte County between - 1999 & 2020 Appendix 2) Summary of Funding Leveraged in Berry Creek and Feather Falls Prior to and After 2018 Appendix 3) Summary of Funding Leveraged in the Past Two Years Appendix 4) Project List Submitted to the Sierra East Side Forest Management Task Force April 2020 Appendix 5) New Projects Added to the CAL FIRE Butte Unit/Community Wildfire Protection Plan in 2020 Appendix 6) A Survivor’s Story from Berry Creek “Tragedy and Triumph” Butte County Fire Safe Council, 5619 Black Olive Dr. Paradise Ca, 95969 [email protected], 530-877-0984 1 Map of the Wildland Urban Interface in Butte County 2 1. Problem Statement In the past 20 years there have been 400,000 acres burned and 20,000 structures destroyed due to wildfire in Butte County (Appendix 1). If you calculate an average of 4 people per structure that equals 80,000 people impacted with structure loss alone, not to mention the loss of community resources, air quality, family impacts and forest loss. -

Download Ordinance

1 Urgency Ordinance No. 4200 2 AN URGENCY ORDINANCE OF THE COUNTY OF BUTTE AMENDING ARTICLE 3 II, OF CHAPTER 54, "NORTH COMPLEX FIRE RECOVERY" OF THE BUTTE 4 COUNTY CODE RELATING TO REBUILDING PERMITS, HAZARD TREE 5 REMOVAL AND NUISANCE ABATEMENT ENFORCEMENT 6 (4/5 VOTE REQUIRED) 7 The Board of Supervisors of the County of Butte ordains as follows: 8 Section !. Findings. 9 This Urgency Ordinance is adopted pursuant to California Government Code Sections 25123(d) 10 and 25131 and shall take effect immediately upon its approval by at least a four-fifths vote of the 11 Board of Supervisors. The Board, in consultation with the Local Health Officer, finds that this 12 Ordinance is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health and safety, based 13 upon the following facts: 14 A. On August 17, 2020, lightning strikes sparked the Bear Fire and the Claremont Fire, both 15 in Plumas County. Conditions of extreme peril to the safety of persons and property within 16 the County of Butte were caused by wildfire known as the North Complex Fire when the 17 Bear and Claremont Fires merged and progressed into the County of Butte on the 8th day 18 of September, 2020, at which time the Board of Supervisors was not in session. A map 19 depicting the North Complex Fire area is attached hereto as Exhibit A. 20 B. California Government Code Section 8630 empowers the County Administrator to 21 proclaim the existence of a local emergency when the county is affected or likely to be 22 affected by a public calamity, subject to ratification by the Board of Supervisors at the 23 earliest practicable time. -

![Additional Documents [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1682/additional-documents-pdf-2921682.webp)

Additional Documents [Pdf]

Economic Impacts of Recent Wildfires on Agriculture in California Daniel A. Sumner, University of California, Davis For presentation at a hearing of the California State Assembly hearing of the Committee on Agriculture, Wednesday November 18, 2020 Economic losses from fire are large, varies and complex. But, before turning to agricultural economic losses we must first be clear that the dominate consequences have been the loss of life and serious injury to individuals in both rural and urban areas. In addition, loss of homes and personal treasures represent much more than monetary loss to the people affected. California wildfires have meant personal tragedy for individuals and families throughout the state. Many farm families, including farm owners and operators and farm employees are among those who suffered tragic losses, including deaths and loss of homes. Calculating the economic impacts of those losses is beyond the scope of the data presented below. Here I consider only the reduced capital value of productive farm assets and loss of agriculture income flows caused by wildfires in recent years. This is just a part of a larger whole. It is important to state at the outset that I do not have and have not seen any up-to-date aggregate assessment of agricultural losses from recent wildfires. The most recent round of fires is too new to have complete data, and even for older fires the impacts are so disparate we may never have a full set of economic models and calculations that covers all losses. In that context, it is vital to highlight examples of specific impacts, which provides vital human context to dry calculations. -

San Bernardino County Reports 158 New COVID-19 Cases, 14 More Deaths Saturday Active Coronavirus Cases Drop While Deaths Increase Due to Data Verification

San Bernardino County adds 158 COVID-19 cases, 14 deaths Saturday 9/13/20, 8:46 AM NEWS San Bernardino County reports 158 new COVID-19 cases, 14 more deaths Saturday Active coronavirus cases drop while deaths increase due to data verification Christopher Damien Palm Springs Desert Sun Published 8:50 p.m. PT Sep. 12, 2020 San Bernardino County officials announced more than 150 new cases of coronavirus and 14 new virus-related deaths among county residents Saturday. The increase in deaths, along with a decrease of about 1,000 active cases reported since Friday, is due to officials revising errors in previously reported data. As of Saturday, San Bernardino County's positivity rate is 9.34%, placing it in the purple, or strictest, of the state's new four-tier framework for reopening. This tier restricts the most business activity and has the most capacity restrictions because COVID-19 is "widespread." The state looks at both rates — positivity and cases — to determine whether a county is allowed to reopen. The purple tier is for counties with widespread COVID-19 cases. It represents counties with a case rate of greater than seven cases per 100,000 people or a positivity rate of 8% or higher. This tier limits indoor operations for many non-essential business sectors, including restaurants. In order for San Bernardino County to move to the next level, the red tier, it has to document fewer than seven new COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents on a rolling seven- https://www.vvdailypress.com/story/news/2020/09/12/san-bernardino…nnounces-158-new-coronavirus-cases-and-14-more-deaths/5782409002/ Page 1 of 4 San Bernardino County adds 158 COVID-19 cases, 14 deaths Saturday 9/13/20, 8:46 AM day average, and its positivity testing rate must be less than 8% in the same period. -

Report on Exempt Timber Harvesting for the Reduction of Fire Hazard Within 150 Feet of Structures and Non-Discretionary Timber Harvest Notice Use and Rule Compliance

DRAFT Report on Exempt Timber Harvesting for the Reduction of Fire Hazard Within 150 Feet of Structures And Non-Discretionary Timber Harvest Notice Use and Rule Compliance July 14, 2021 Thomas W. Porter, Director California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection J. Keith Gilless, Chair State Board of Forestry and Fire Protection Wade Crowfoot, Secretary for Natural Resources California Natural Resources Agency Gavin Newsom, Governor State of California DRAFT A note for reading this report: The nature of monitoring complex regulatory frameworks and ecological variables involves detailed, sometimes complicated quantitative analysis. To help all readers, this report includes: • A detailed Executive Summary of the full report and key findings • Gray text boxes and bolded text within the main body of the report to highlight and summarize each section or important findings, followed by detailed analysis results for readers that wish to know more about the outcomes of the monitoring and findings Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ iii Monitoring Report on 1038(c) 0-150 Foot Fire Hazard Reduction Exemptions ............... 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 8 Background .............................................................................................................. 8 Monitoring Overview ............................................................................................... -

Sierra Nevada Conservancy 2020 Annual Report

SIERRA NEVADA CONSERVANCY 2020 (Mega) Fire Season Projects Protected Communities from Wildfire Program Milestones Looking Ahead sierranevada.ca.gov Terrence O'Brien, Governing Board Chair Angela Avery, Executive Officer Julie Alvis, Deputy Executive Officer CONTENTS Working Through Tragedy & Towards Resilience 1 2020 (Mega) Fire Season 2 SNC Projects Protected Communities from Wildfire 6 SNC Program Milestones 10 Looking Ahead 14 Cover: Drone photography of the North Complex Fire taken in October 2020 shows how fuel treatments by the Plumas County Fire Safe Council were effective in changing burn severity near dispersed cabins off of Quincy-La Porte Rd, in Plumas County, CA. The Sierra Nevada Conservancy is a state agency with the mission to initiate, encourage, and support efforts to improve the environmental, economic, and social well-being of the Sierra Nevada Region, its communities, and the citizens of California. WORKING THROUGH TRAGEDY & TOWARDS RESILIENCE The past year was a difficult one for California and the Sierra Nevada. A pandemic ended—and It is important to note that not all fire is bad, but upended—lives across the globe and while many in these large damaging Sierra Nevada megafires are California were still struggling to adapt to this new unlike the smaller, less intense, and ecologically abnormal, the state endured a record-shattering beneficial fires that have shaped the landscape for wildfire season. millennia. They degrade rather than renew and, as we witnessed in 2020, their impacts threaten our California way of life. Despite these twin crises, the Sierra Nevada Conservancy (SNC) continued to work through tragedy and towards resilience. -

Benevolent Enhancement: a Time for Growth

ISSUE 01 // JULY 2021 The California Fire Foundation - assisting families of fallen firefighters, firefighters and the FIRE LINES communities they protect. /// PAGE 4 /// PAGE 6 /// PAGE 7 CALIFORNIA FIRE FOUNDATION: FUNDRAISER MESSAGE FROM HELPING HEAL CALIFORNIA SPOTLIGHT OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Photos: Anthony Guevara/ FOX26 and James Parr BENEVOLENT ENHANCEMENT 2 “THE FIRE WAS TOO FIERCE, community his own house was to tell people that everything was there was nothing that could be burning, and he would soon get lost,” said Fire Chief James Parr. done,” said Fire Chief James Parr word that it too was lost to the Just like the Pine Ridge Vol- of the Pine Ridge Volunteer Fire flames. The fire came through the unteers, thousands of California Department (PRVFD). Pine Ridge community in 30 min- firefighters work tirelessly for our On September 4, 2020, the Creek utes and 66 out of the 88 homes in communities, day in and day out. Fire started near Shaver Lake and the area were destroyed. When catastrophic wildfires or burned 379,895 acres. James Parr Fifteen out of the twenty-four natural disasters strike, many of our was a street away from his home volunteer fire personnel at PRVFD firefighters remain on the front lines, Benevolent fighting a really fast-moving fire lost their homes that day. Many had even as their own homes are lost. Enhancement: with 100-200ft flames. At the time lived in the area for decades. “We’re This is the brutal reality for Cali- he had no idea that while he fought all basically friends and family up fornia firefighters and is why in 2018, A Time for Growth tirelessly to protect a neighboring here and this ripped us apart. -

Bulletin 2020-11 Mandatory Moratorium on Cancellations And

RICARDO LARA CALIFORNIA INSURANCE COMMISSIONER AMENDED* BULLETIN 2020-11 TO: All Admitted and Non-Admitted Insurers Writing Residential Property Insurance in California FROM: Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara DATE: November 6, 2020 RE: Mandatory Moratorium on Cancellations and Non-Renewals of Policies of Residential Property Insurance After the Declaration of a State of Emergency *This amendment to Bulletin 2020-11 issued on November 5, 2020 provides additional information regarding ZIP Codes within or adjacent to the fire perimeters for the fires identified in the Governor’s various Emergency Declarations discussed herein. As enacted by Senate Bill 824 (Lara, Chapter 616, Statutes of 2018) Insurance Code section 675.1, subdivision (b)(1) provides: “An insurer shall not cancel or refuse to renew a policy of residential property insurance for a property located in any ZIP Code within or adjacent to the fire perimeter, for one year after the declaration of a state of emergency as defined in Section 8558 of the Government Code, based solely on the fact that the insured structure is located in an area in which a wildfire has occurred. This prohibition applies to all policies of residential property insurance in effect at the time of the declared emergency.” (Emphasis added.) Section 675.1, subdivision (d) defines “policy of residential property insurance” as follows: “…policy residential property insurance” has the meaning described in subdivision (a) of Section 10087.” (Emphasis added.) CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF INSURANCE PROTECT • PREVENT -

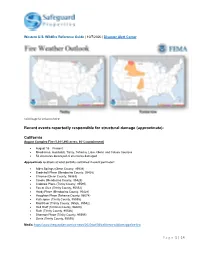

Safeguard Properties Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide

Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/7/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Click image for enhanced view Recent events reportedly responsible for structural damage (approximate): California August Complex Fire (1,011,493 acres; 60% containment) August 16 – Present Mendocino, Humboldt, Trinity, Tehama, Lake, Glenn and Colusa Counties 52 structures destroyed; 6 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Alder Springs (Glenn County, 95939) Bredehoft Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Chrome (Glenn County, 95963) Covelo (Mendocino County, 95428) Crabtree Place (Trinity County, 95595) Forest Glen (Trinity County, 95552) Hardy Place (Mendocino County, 95428) Houghton Place (Tehama County, 96074) Kettenpom (Trinity County, 95595) Mad River (Trinity County, 95526, 95552) Red Bluff (Tehama County, 96080) Ruth (Trinity County, 95526) Shannon Place (Trinity County, 95595) Zenia (Trinity County, 95595) Media: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/oct/06/california-wildfires-gigafire-first P a g e 1 | 14 Western U.S. Wildfire Reference Guide | 10/7/2020 | Disaster Alert Center Bobcat Fire (115,796 acres; 89% containment) September 6 – Present Los Angeles County *Northeast of Cogswell Reservoir, San Gabriel Canyon 163 structures destroyed; 47 structures damaged Approximate locations at least partially contained in event perimeter: Big Rock Springs (Los Angeles County, 93544) Hidden Springs (Los Angeles County, 93550) Juniper Hills (Los Angeles County, 93543, 93553)) Littlerock (Los -

Wildfires Facts + Statistics

Facts + Statistics: Wildfires Catastrophes IN THIS FACTS + STATISTICS Wildland fires Wildfires by year Annual Number of Acres Burned in Wildland Fires, 1980-2020 Top 10 States At High To Extreme Wildfire Risk, 2019 (1) Wildfires By State, 2020 Top 10 States For Wildfires Ranked By Number Of Fires And By Number Of Acres Burned, 2020 Wildfire Losses In The United States, 2010-2019 (1) Top 10 Costliest Wildland Fires In The United States (1) Top 10 Largest California Wildfires (1) Top 10 Most Destructive California Wildfires (1) Top 10 Deadliest California Wildfires (1) SHARE THIS DOWNLOAD TO PDF Wildland fires As many as 90 percent of wildland fires in the United States are caused by people, according to the U.S. Department of Interior. Some human-caused fires result from campfires left unattended, the burning of debris, downed power lines, negligently discarded cigarettes and intentional acts of arson. The remaining 10 percent are started by lightning or lava. According to Verisk’s 2019 Wildfire Risk Analysis 4.5 million U.S. homes were identified at high or extreme risk of wildfire, with more than 2 million in California alone. Wildfires by year 2021: This year’s wildfire season is predicted to be another severe one. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor by August 31, about 90 percent of land in the Western states was experiencing moderate to severe drought. Compounded by June’s heat wave, the threat of wildfires appeared a month ahead of schedule. From January 1 to September 19, 2021 there were 45,118 wildfires, compared with 43,556 in the same period in 2020, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.