Frozen Frames There Are Contrasts-The Great Mahatma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chandresh Kumari Katoch by : INVC Team Published on : 14 Nov, 2012 07:51 PM IST

The exhibition is a milepost in itself portraying the memories of the Indian independence movement : Chandresh Kumari Katoch By : INVC Team Published On : 14 Nov, 2012 07:51 PM IST INVC,, Delhi,, The Union Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch here today inaugurated an exhibition entitled ‘Visual Archives of Kulwant Roy’. The exhibition has been organised by the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Ministry of Culture and curated by Aditya Arya, who has played a pivotal role in the formation of the India Photo Archive Foundation of which he is a Trustee. The Secretary Culture Smt. Sangita Gairola was the Guest of Honour on the occasion. Speaking at the inaugural function, Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch has said that the exhibition is a milepost in itself portraying the memories of the Indian independence movement, the decisive political events, protests, marches and eminent leaders of the mainstream nationalist politics. The exhibition also pays its due homage to the foremost and unsung photojournalists who assiduously captured these public moments but whose works have been lost over the time. The exhibition showcases an earnest selection of the diverse photographs taken by Kulwant Roy, one of the first free-lance photo-journalists who worked through the pre and post-independence era of Modern India, an era that witnessed many nationalist upsurges that shaped the political, constitutional, and economic future of the country. In this exhibition, the NGMA is displaying some of the rarest negatives and prints of MAHATMA GANDHI recently discovered and restored. This collection represents the work Kulwant Roy (1914-1984). Starting from 1930s to the 960s, his work follows mainstream national history. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

Middle Eastern Politics & Culture

Middle Eastern Politics & Culture: TODAY & YESTERDAY By Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective origins.osu.edu Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Middle Eastern Politics 1 The Secular Roots of a Religious Divide in Contemporary Iraq 2 A New View on the Israeli-Palestine Conflict: From Needs to Narrative to Negotiation 15 Erdoğan’s Presidential Dreams, Turkey’s Constitutional Politics 28 Clampdown and Blowback: How State Repression Has Radicalized Islamist Groups in Egypt 40 A Fresh Start for Pakistan? 51 Alawites and the Fate of Syria 63 Syria's Islamic Movement and the 2011-12 Uprising 75 From Gaza to Jerusalem: Is the Two State Solution under Siege? 88 The Long, Long Struggle for Women's Rights in Afghanistan 101 Egypt Once Again Bans the Muslim Brotherhood, Sixty Years Later 112 Understanding the Middle East 115 Afghanistan: Past and Prospects 116 Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography 117 A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind 120 Chapter 2: Water and the Middle East 123 Baptized in the Jordan: Restoring a Holy River 124 Who Owns the Nile? Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia’s History-Changing Dam 139 Outdoing Panama: Turkey’s ‘Crazy’ Plan to Build an Istanbul Canal 150 Chapter 3: Islam, Christianity, and Culture in the Middle East 163 Two Popes and a Primate: The Changing Face of Global Christianity 164 What's in a Name?: The Meaning of “Muslim Fundamentalist” 177 Tradition vs Charisma: The Sunni-Shi'i Divide in the Muslim World 185 The Dangers of Being a Humorist: Charlie Hebdo Is Not Alone 192 Civilizations of Ancient Iraq 196 Chapter 4: Maps and Charts 200 About Origins 222 Chapter 1 Middle Eastern Politics (Image: Siria Bosra by Jose Javier Martin Esparto, Flickr.com (CC BY-NC- SA 2.0)) Section 1 The Secular Roots of a Religious Divide in Contemporary Iraq EDITOR’S NOTE: By STACY E. -

Annual Report 2008-2009

Annual Report 2008-2009 Ministry of External Affairs Cover Photo: Model of Jawahar Lal Nehru Bhawan, the Headquarters of the Ministry of External Affairs, under construction on Janpath, New Delhi Published by: Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi This Annual Report can also be accessed at website: www.mea.gov.in Designed and printed by: Cyberart Informations Pvt. Ltd. 1517 Hemkunt Chambers, 89 Nehru Place, New Delhi 110019 Website: www.cyberart.co.in Telefax: 0120-4231617 Contents Introduction and Synopsis i-xvi 1 India’s Neighbours 1 2 South East Asia and the Pacific 17 3 East Asia 30 4 Eurasia 34 5 The Gulf, West Asia and North Africa 41 6 Africa (South of Sahara) 54 7 Europe 79 8 The Americas 93 9 United Nations and International Organizations 108 10 Multilateral Economic Relations 125 11 Technical & Economic Cooperation and Development Partnership 132 12 Investment and Technology Promotion 135 13 Policy Planning and Research 136 14 Protocol 139 15 Consular, Passport and Visa Services 145 16 Administration and Establishment 149 17 Coordination 153 18 External Publicity 155 19 Public Diplomacy Division 157 20 Foreign Service Institute 161 21 Indian Council for Cultural Relations 163 22 Indian Council of World Affairs 168 23 Research and Information System for Developing Countries 170 24 Library 175 Appendices Appendix I: Cadre strength at Headquarters and Missions abroad during 2008-09 (including Posts budgeted by Ministry of Commerce and those ex-cadred etc.) 179 Appendix II: Data on recruitment -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA SUMMER TABESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2009 G SUMMER/JUNE 2009 Tir – AmordadJOURJO – Shehrever 1378 AY (Fasli) G Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY, Fravardin 1379 AY (Shenshai) N G Spendarmad 1378AL AY, Fravardin – Ardibehesht 1379 AY (Kadimi) Chicago area Zarathushtis celebrate the arrival of the Spring Equinox in a special sunrise ceremony at the lakefront planetarium Also Inside: Pakistan Revisited Passport to Persia Festival ZAPANJ at the Philadelphia Museum Navroze Celebrations Across North America PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 2 Summer / Tabestan 1378 AY 3747 ZRE President Bomi Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel 5 Financial Report Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 7 Coming Events [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, 9 NOROOZ -Celebrations Around www.khanizadeh.info the World Cover design: Feroza Fitch, [email protected] 23 JUNGALWALLA LECTURE Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 65 NOROOZ Photo Montage Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : 74 PAKISTAN REVISITED [email protected] Yezdi Godiwala [email protected] 95 Mumbai’s Last Parsi Restaurants Fereshteh Khatibi: [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 99 A Secret Place: San Jose Darbe Mahrukh -

The Carvan Feb 2 Issue

Photography Reimagining History The newly discovered visual archives of Kulwant Roy shed light on Independence-era India Kristen V Brown here are stories of Kulwant of a clash of ego.” later, in December 2007, Arya Roy, his spirit broken, spend- Little did Arya know he would decided enough was enough – it was T ing the last years of his life eventually spend years tracking time to open the boxes. “I knew that hunting through Delhi’s post offices Roy’s ghosts. once I opened them, there would be and garbage dumps for his lost The industry Roy had first no time. There would be no looking work. The images, photographed become enamoured with had long back,” says Arya. during a global trek that would last since vanished by the time of his He had an inkling that what he the first three years of the 1960s, death – a new era of aggressive had been hiding away in the dusty had been shipped from stops along young photojournalists had taken corners of an upper story guest bed- the way to his home in Mori Gate. over the industry. Gone were the room was important. The images, He returned to India in 1963; he days when press enjoyed easy access which number well above 10,000, learned the boxes had never and chummy relationships with sprawled across the entirety of the reached. politicians. bedroom. Neatly collected in Aditya Arya remembers this Roy Developing leukaemia later in envelopes and boxes with labels like – a depressed, jaded bachelor – as a life, Roy would die broke, alone and “Muslim League photos,” some of daily fixture at the dinner table. -

Homai Imqlgysmgnj

HomaiVyarawalla Homai imqlgysmgnj to a lostera injournalism, saysJaideepSen. ,/ m ry +!i,,: ,';,i.'. :.'I Genteel does it (Rreht) The Mole Station at Ballard Pier, Bombay, and (facing lage) Homai Vyaranalln nithher SleedGralhic Pacemaker Quaher Phte camera, early- 1 940s ; images courteslt Thz Homai Vy ar aw alln Ar chiu e /Alkazi Colle ction of Pho tograp hy The irony was hard to miss at the ceremony held earlier this year at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, as Homai Vyarawalla took the dais to receive the Padma Vibhushan, encircled by a flash mob of lensmen. On this one occasion, the now-frail, yet spirited photographer from the city of Navsari, in Gujarat, didn't require the endorsement of her trusted press corps badge to gain access into the presidential residence, the annexes and yawning corridors of which she has been rather familiar with, albeit when the edifice was known as the Viceroy's House. Through the 1940s and'50s, Vyarawalla was a recognised figure in these magisterial interiors, gaining nods from the then curator of a retrospective show of her work President of India Rajendra Prasad, and that will open at the National Gallery of 'l tell people that she's especially from the then Prime Minister Modern Art in the city this fortnight. "Those Jawaharlal Nehru. For close to three decades were different times," said Gadihoke, who not interested in thereon, Vyarawalla's name would become has also authored a book on Vyarawala, and synonymous with candid shots of Nehru - discussed her work in a fi1m. "There was a becomingwealthy!' as he hosted dignitaries, broke intir sense of ethics and self-respect. -

High Politics Subject: History Unit

High Politics Subject: History Unit: Independence and Partition Lesson: High Politics Lesson Developer Srinath Raghavan College/Department : Senior Fellow, Center for Policy Research, New Delhi and Lecturer in Defence Studies, King’s College, London Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi High Politics Table of contents Chapter 12: Independence and Partition 12.1: High politics Summary Exercises Glossary Further readings Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi High Politics 12.1: High politics The Second World War ended in Europe on 7 May 1945. Five weeks later the Congress Working Committee was released from prison. Soon after, negotiations for the future of India commenced. By the time the Raj folded up in mid-August 1947, there were two dominions of India and Pakistan. The question of why Partition accompanied Independence has given rise to an enormous body of historical writing. Given its tremendous human cost and its continued implications for the subcontinent, it is not surprising that the subject invites exploration from newer angles and perspectives. The existing literature falls into four broad categories of works: the ‘high politics’ or the negotiations between the British and Indian leaders; provincial politics or the study of how the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan played out in Punjab, Bengal, and to lesser extent in UP, North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), and Sindh; popular movements and their impact on political negotiations at various levels; and the human dimension of Partition with an emphasis on the victims of violence, especially women. In this lesson, we will focus on negotiations between the British, the Muslim League and the Congress. -

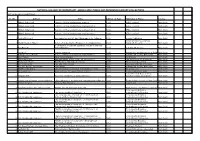

National Gallery of Modern Art , Bengaluru Public Art Reference Library Collections

NATIONAL GALLERY OF MODERN ART , BENGALURU PUBLIC ART REFERENCE LIBRARY COLLECTIONS LIST OF BOOKS COLLECTIONS Sl. No. Author Title Edition & Year Publisher & Place Source 1 McNeil, Peter (cd) Fashion : Critical and primary sources 2009 BERG : Oxford From Delhi 2 McNeil, Peter (cd) Fashion : Critical and primary sources:18th c 2009 BERG : Oxford From Delhi 3 McNeil, Peter (cd) Fashion : Critical and primary sources:19th C 2009 BERG : Oxford From Delhi 4 McNeil, Peter (cd) Fashion : Critical and primary sources:20th C 2009 BERG : Oxford From Delhi 5 Crabie,Michael J Designing the world's best Museums & Art Galleries 2003 Images Publishing From Delhi Indian art history Congress 6 Maruti Nandan Tiwari Indian art & Aesthetics:Endevours in Interpretation 2004 Guwahati (Assam) From Delhi A confluence of distilled essences:The art of chameli 7 Roy,Ranesh Ramachandran 2008 Vedehra Art Gallery From Delhi 8 Jacob S.S Jeypore Enamels 2008 Arya Books International New Delhi From Delhi 9 Ed-Yashodhara Dalmia Indian contemporary Art Post Independence 2007 Vadehra Art Gallery New Delhi From Delhi 10 Ravi Kapoor Raza library Rampur 2008 Raj Bhavan From Delhi 11 Appasamy,Jaya Abanindranath Tagore & the art of his times 1968 Lalit Kala Academi New Delhi From Delhi 12 Text:Swati Chopra Buddhism on the path of nirvana 2005 Mercury Books London From Delhi 13 Ed : Ferrier.R.W The arts of the Persia 1989 Yabe University Press London From Delhi 14 By: Idea Images Exchanges Tyeb Mehta 2005 Vadehra Art Gallery New Delhi From Delhi 15 Madhumitha Dutta Lets know -

Contemporary Indian Photography

Contemporary Indian Photography A long read on Indian photography Written by Tanvi Mishra Commissioned by DutchCulture, Centre for International Cooperation. 12-04-2017 1 This long read was produced as part New Cultural Horizon India program of DutchCulture.For more information - [email protected] or check out our website DutchCulture.nl Table of Contents/ Inhoudsopgave INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 4 HISTORY OF INDIAN PHOTOGRAPHY ................................................................................. 5 Photography And The Empire ............................................................................................. 5 Adoption By Indian Practitioners ......................................................................................... 6 Advent Of Press Photography And Photojournalism In The 20Th Century ......................... 7 CONTEMPORARY INDIAN PHOTOGRAPHIC PRACTICE AND THE LONG TERM DOCUMENTARY PROJECT .......................................................... 12 The Self And The Family As The Protagonist.................................................................... 12 Gender And Body Politics ................................................................................................. 15 Demographic And The Landscape .................................................................................... 18 Fiction, Humour and Post-Photography ........................................................................... -

Annual Report 2015-16

Annual Report 2015-16 Ministry of Culture Government of India Contents Contents Contents 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview 1 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India 5 2.2 Museums 27 2.2a National Museum 27 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art 36 2.2c Indian Museum 50 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall 52 2.2e Salar Jung Museum 54 2.2f Allahabad Museum 59 2.2g National Council of Science Museum 62 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities 64 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology 64 2.3b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property 66 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) 67 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) 69 2.6 UNESCO Matters 71 2.7 National Monuments Authority 73 2.8 National Missions 75 2.8a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities 75 2.8b National Mission for Manuscripts 75 2.8c National Mission on Libraries 78 2.8d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites 79 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama 83 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts 87 3.3 Akademies 94 3.3a Sahitya Akademi 94 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi 98 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi 104 iv Contents 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training 109 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation 114 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres 118 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre 118 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre 122 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre 124 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre 126 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre 128 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre 129 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre 132 4.