High Politics Subject: History Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009)

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009) New Delhi 151 Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Chairman: Mr. Justice G. N. Ray Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANIZATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPER Shri Vishnu Nagar Editors Guild of India, All India Nai Duniya, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Uttam Chandra Sharma All India Newspaper Editors’ Muzaffarnagar Conference, Editors Guild of India, Bulletin, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Vijay Kumar Chopra All India Newspaper Editors’ Filmi Duniya, Conference, Editors Guild of India, Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Sheetla Singh Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Ms. Suman Gupta Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Saryu Tat Se, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Editors of English Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Yogesh Chandra Halan Editors Guild of India, All India Asian Defence News, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri K. Sreenivas Reddy Indian Journalists Union, Working Visalaandhra, News Cameramen’s Association, Andhra Pradesh Press Association Shri Mihir Gangopadhyay Indian Journalists Union, Press Freelancer, (Ganguly) Association, Working News Bartaman, Cameramen’s Association West Bengal Shri M.K. Ajith Kumar Press Association, Working News Mathrubhumi, Cameramen’s Association, New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Joginder Chawla Working News Cameramen’s Freelancer Association, Press Association, Indian Journalists Union Shri G. -

INTERNATIONAL GCSE History (9-1) TOPIC BOOKLET: Colonial Rule and the Nationalist Challenge in India, 1919-47 Pearson Edexcel International GCSE in History (4HI1)

INTERNATIONAL GCSE History (9-1) TOPIC BOOKLET: Colonial rule and the nationalist challenge in India, 1919-47 Pearson Edexcel International GCSE in History (4HI1) For fi rst teaching September 2017 First examination June 2019 Contents Page 1: Overview Page 3: Content Guidance Page 16: Student Timeline Overview This option is a Depth Study and in five Key Topics students learn about: 1. The Rowlatt Acts, Amritsar and the Government of India Act, 1919 2. Gandhi and Congress, 1919-27 3. Key developments 1927-39 4. The impact of the Second World War on India 5. Communal violence, independence and partition, 1945-47. The content of each depth study is expressed in five key topics. Normally these are five periods in chronological order, but some options contain overlapping dates where a new aspect is introduced. Although these clearly run in chronological sequence, they should not be taken in isolation from each other – students should appreciate the narrative connections that run across the key topics. Questions may cross these topics and students should appreciate the links between them in order to consider, for example, long-term causes and consequences. The teaching focus should enable students to: gain knowledge and understanding of the key features and characteristics of historical periods develop skills to analyse historical interpretations 1 develop skills to explain, analyse and make judgements about historical events and periods studied, using second-order historical concepts (causation, consequence and significance). Outline – why students will engage with this period in history Students study a period of huge significance in the challenge to British colonial rule and the creation of new states in the sub-continent. -

Chandresh Kumari Katoch by : INVC Team Published on : 14 Nov, 2012 07:51 PM IST

The exhibition is a milepost in itself portraying the memories of the Indian independence movement : Chandresh Kumari Katoch By : INVC Team Published On : 14 Nov, 2012 07:51 PM IST INVC,, Delhi,, The Union Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch here today inaugurated an exhibition entitled ‘Visual Archives of Kulwant Roy’. The exhibition has been organised by the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Ministry of Culture and curated by Aditya Arya, who has played a pivotal role in the formation of the India Photo Archive Foundation of which he is a Trustee. The Secretary Culture Smt. Sangita Gairola was the Guest of Honour on the occasion. Speaking at the inaugural function, Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch has said that the exhibition is a milepost in itself portraying the memories of the Indian independence movement, the decisive political events, protests, marches and eminent leaders of the mainstream nationalist politics. The exhibition also pays its due homage to the foremost and unsung photojournalists who assiduously captured these public moments but whose works have been lost over the time. The exhibition showcases an earnest selection of the diverse photographs taken by Kulwant Roy, one of the first free-lance photo-journalists who worked through the pre and post-independence era of Modern India, an era that witnessed many nationalist upsurges that shaped the political, constitutional, and economic future of the country. In this exhibition, the NGMA is displaying some of the rarest negatives and prints of MAHATMA GANDHI recently discovered and restored. This collection represents the work Kulwant Roy (1914-1984). Starting from 1930s to the 960s, his work follows mainstream national history. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

Summit Failures and Cabinet Obstacles, August 1944–July 1945

August 1944–July 1945 4 Summit Failures and Cabinet Obstacles, August 1944–July 1945 S THE UNITED STATES took upon itself the lion’s share of the Allied war against Japan, Roosevelt’s frustration at Churchill’s in- A transigence over India grew stronger. FDR’s personal envoy, Am- bassador Phillips, reported, after returning to Washington, that when he talked to Churchill about India, “Churchill banged the table and said ‘I have always been right about Hitler and everyone else in Europe. I am also right about Indian policy, any change in Indian policy now will mean a blood bath.’”1 Whenever Roosevelt himself tried to discuss India with Churchill he received “a blunt cold shoulder.” By late summer of 1944 he entirely agreed with Phillips’s forthright report of what needed to be done about British policy in India. Since India would have to become a major base of future operations against Burma and Japan, “We should have around us a sympathetic India rather than an indifferent and possibly hostile India,” Phillips wrote. Indi- ans currently felt that “they have no voice in the Government and therefore no responsibility in the conduct of the war. They feel that they have nothing to fight for as they are convinced that the professed war aims of the United Nations do not apply to them. The British Prime Minister in fact has stated that the provisions of the Atlantic Charter are not applicable to India.” The Indian Army was “purely mercenary,” Phillips told FDR, adding that Gen- eral Stilwell was quite worried about “the poor morale” of Indian officers. -

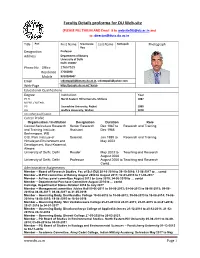

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Prof. First Name Sreenivasa Last Name Kottapalli Photograph Rao Designation Professor Address Department of Botany University of Delhi Delhi 110007 Phone No Office 27667525 Residence 27666898 Mobile 9313294607 Email [email protected], [email protected] Web-Page http://people.du.ac.in/~ksrao Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. North Eastern Hill University, Shillong 1987 M.Phil. / M.Tech. PG Saurashtra University, Rajkot 1980 UG Andhra University, Waltair 1978 Any other qualification Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Central Sericulture Research Senior Research Dec 1987 to Research and Training and Training Institute, Assistant Dec 1988 Berhampore, WB G.B. Pant Institute of Scientist Jan 1989 to Research and Training Himalayan Environment and May 2003 Development, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora University of Delhi, Delhi Reader May 2003 to Teaching and Research August 2008 University of Delhi, Delhi Professor August 2008 to Teaching and Research Contd.. Administrative Assignments Member – Board of Research Studies, Fac of Sci (DU) 30-10-2014 to 29-10-2016; 13-06-2017 to …contd Member – M.Phil committee of Botany August 2008 to August 2011; 12-03-2015 to 11-03-2017 Member – Ad-hoc panel committee August 2012 to June 2015; 24-06-2015 to … contd Member – Departmental Purchase Committee August 2014 to … contd Incharge, Departmental Stores October -

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2012-2013 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT (%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 67059 0.002525667 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 579134 0.021812132 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1172263 0.044151362 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 373181 0.01405525 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 390958 0.014724791 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 172950 0.006513878 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 366211 0.013792736 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 398436 0.015006438 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 180263 0.00678931 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 265972 0.010017399 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 4172 0.000157132 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 297035 0.011187336 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410280 HELAPURI NEWS TELUGU DAILY(E) 67795 0.002553387 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 152550 0.005745545 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410405 VASISTA TIMES TELUGU DAILY(E) 62805 0.002365447 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 369397 0.013912732 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 239960 0.0090377 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 209853 -

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan

Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors ASIA PAPER November 2008 Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan Papers from a Conference Organized by Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and the Institute of Security and Development Policy (ISDP) in Islamabad, October 29-30, 2007 Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema Maqsudul Hasan Nuri Muneer Mahmud Khalid Hussain Editors © Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Islamabad Policy Research Institute House no.2, Street no.15, Margalla Road, Sector F-7/2, Islamabad, Pakistan www.isdp.eu; www.ipripak.org "Political Role of Religious Communities in Pakistan" is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. Through its Silk Road Studies Program, the Institute runs a joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This report is published by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and is issued in the Asia Paper Series with the permission of IPRI. -

Download Coverage File

CONFIDENTIAL Digisakshar.org Launch PUBLIC RELATIONS & COMMUNICATIONS – PROJECT REPORT 5th August-20th August 2020 Submitted by ADRIFT COMMUNICATIONS & INFLUENCER MARKETING www.adriftcommunications.com COVERAGE INDEX NEW DELHI S. No. Date Publication 1 13th August, 2020 The Economic Times (online) 2 13th August, 2020 Financial Express (online) 3 13th August, 2020 Deccan Herald (online) 4 13th August, 2020 Punjab Kesari (online) 5 11th August, 2020 Dainik Jagran (online) 6 05th August, 2020 www.Expresscomputer.in 7 05th August, 2020 www.crn.in 8 05th August, 2020 www.CSRJournal.in 9 05th August, 2020 www.CSRMandate.org 10 05th August, 2020 www.humancapitalonline.com 11 05th August, 2020 www.indiaeducationdiary.in 12 05th August, 2020 www.indiacsr.in 13 06th August, 2020 www.sightsinplus.com 14 07th August, 2020 www.ciol.com 15 07th August, 2020 www.crossbarriers.org 16 07th August, 2020 Deshbandhu 17 08th August, 2020 Aaj 18 08th August, 2020 Virat Vaibhav 19 08th August, 2020 Dilli Dil Se (Facebook pg) www.adriftcommunications.com 20 13th August, 2020 Thodkyaat.com (Marathi) LUCKNOW S. No. Date Publication 1 12th August, 2020 Hindustan Times 2 12th August, 2020 Pioneer 3 07th August, 2020 Dainik Jagran 4 12th August, 2020 Rashtriya Sahara 5 14th August, 2020 Aaj 6 07th August, 2020 Spasht Awaz 7 06th August, 2020 Voice of Lucknow 8 06th August, 2020 Nyayadheesh 9 06th August, 2020 Everyday News 10 06th August, 2020 Daily News Activist 11 06th August, 2020 Swatantra Bharat 12 06th August, 2020 Rashtriya Prastavana 13 10th August, 2020 Tarun Mitra www.adriftcommunications.com INDORE S. No. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Mcqs of Past Papers Pakistan Affairs

Agha Zuhaib Khan MCQS OF PAST PAPERS PAKISTAN AFFAIRS 1). Sir syed ahmed khan advocated the inclusion of Indians in Legislative Council in his famous book, Causes of the Indian Revolt, as early as: a) 1850 b) 1860 c) 1870 d) None of these 2). Who repeatedly refers to Sir Syed as Father of Muslim India and Father of Modern Muslim India: a) Hali b) Abdul Qadir c) Ch. Khaliquz Zaman d) None of these 3). Military strength of East India Company and the Financial Support of Jaggat Seth of Murshidabad gave birth to events at: a) Plassey b) Panipat c) None of these 4). Clive in one of his Gazettes made it mandatory that no Muslim shall be given an employment higher than that of chaprasy or a junior clerk has recorded by: a) Majumdar b) Hasan Isphani c) Karamat Ali d) None of these 5). The renowned author of the Spirit of Islam and a Short History of the Saracens was: a) Shiblee b) Nawab Mohsin c) None of these ( Syed Ameer Ali) 1 www.css2012.co.nr www.facebook.com/css2012 Agha Zuhaib Khan 6). Nawab Sir Salimullah Khan was President of Bengal Musilm Leage in: a) 1903 b) 1913 c) 1923 d) None of these (1912) 7). The first issue of Maualana Abul Kalam Azads „Al Hilal‟ came out on 13 July: a) 1912 b) 1922 c) 1932 d) None of these 8). At the annual session of Anjuman Hamayat Islam in 1911 Iqbal‟s poem was recited, poetically called: a) Sham-o-Shahr b) Shikwa c) Jawab-i-Shikwa d) None of these 9).