Ethiopia Eritrea Somalia Djibouti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somalia: Humanitarian Dashboard February 2013 | Issued on 27 March

Somalia: Humanitarian Dashboard February 2013 | Issued on 27 March KEY INDICATIVE Situation overview CONSOLIDATED APPEAL: 2013 FIGURES Malnutrition continues to be a challenge in Somalia despite the continuous Total resources available improvement in the humanitarian situation. The Food Security and Nutrition 1.05million Analysis Unit (FSNAU) highlights that improvements in food security do not 9.9% people in imply immediate reduction of malnutrition rates due to several contributing humanitarian emergency factors such as disease, limited sanitation structures and inadequate food and crisis 1 (FSNAU, 2013) intake. Nutrition partners are continuing to strengthen their preventive programmes to address these underlying causes, while they continue working 1.67 million on emergency response. As with all other humanitarian partners, one of the people in stress main challenges remains access to beneficiaries especially in parts of southern (FSNAU, 2013) Somalia. Humanitarians are concerned about the steady increase in cases of acute Requirements 1.1 million watery diarrhoea in Banadir and Lower Shabelle regions. In February alone, internally displaced people 2 565 suspected cases were reported and the number is expected to increase (UNHCR, 2012) with the start of the rainy season in April. Health partners are working on HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN FUNDING pre-positioning of medical supplies to be able to respond rapidly to the foreseen APPEAL (2013) FUNDING (2013) COVERAGE (2013) 215,000 cyclical increase of needs during the rainy season especially in the riverine (million US $) (million US $) acutely malnourished children areas in the south. under 5 (FSNAU, as of January, 2013) 1.3bn 131m 9.9% BASELINE PROGRESS TOWARDS STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES People affected People targeted People reached (25/03/2013) Revised Funding Population Percent covered 7.5 m Cluster and indicator requirements received (UNDP, 2005) 0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 (%) million people (million $) (million $) GDP per capita (UN statistics $284 Education - number of learners 61.6 2.8 4.7% division) % pop. -

Somalia Emergency Weekly Health Update

Somalia Emergency Weekly Health Update The Somalia emergency weekly health update aims to provide an overview of the health activities conducted by WHO and health partners in Somalia. It compiles health information including nine health events (epidemiological surveillance) reported in Somalia, information on ongoing conflicts in some regions of Somalia and health responses from partners. For further information please contact: Pieter Desloovere – WHO Communications Officer - [email protected] - T: +254 733 410 984 BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS Reporting dates 15 - 21 September 2012 (reflecting Epidemiological week 37) Since 5 September, over 180 suspected cholera cases and 18 deaths have been reported from Hoosingow (most affected), Dhobley, Waraq and Afmadow. Ten stool samples were collected from Hoosingow in Badade district and four from Dhobley in Afmadow district, and are being tested in the lab. Preliminary results are expected on Saturday 22 September. ©HIJRA IN FOCUS STORY: Dangerous pregnancy complications in Badbaado IDP camp, Mogadishu For the past 10 months, Nadifo Mohamoud, a young mother, has been living in Badbaado IDP camp, Mogadishu. She has a small kiosk in front of her makeshift shelter and she vends clay-made ovens. Last Sunday, Nadifo’s mother ran to the Badbaado health clinic, supported by health partner HIJRA. Nadifo fainted while she was trying to cook food on an open fire near her makeshift shelter. Nadifo is 9 months pregnant and is expecting her baby any time. This is not her first pregnancy; she has already given birth to three children. Unfortunately, two of her children passed away before they reached Medical staff of HIJRA put Nadifo on a stretcher to the age of five. -

2012 Humanitarian Bulletin Template

Humanitarian Bulletin Somalia January 2013 | Issued on 8 February 2013 In this issue New food security data released P.1 Relocation of displaced in capital P.2 HIGHLIGHTS Increased returns from Kenya P.3 People in food security crisis reduced by half, but gains Insecurity key access challenge P.4 could reverse without humanitarian support. Women and children lining up to be screened for malnutrition at one of WFP’s five special nutrition centres in Kismayo. Credit: WFP/David Orr The Government of Somalia plans to relocate internally displaced people from centre Data confirms food security improvement of Mogadishu. Despite gains, situation remains fragile with 1 million people still in crisis Aid workers visit and deliver aid in areas where access The number of people in food security crisis, unable to meet basic food needs without assistance, reduced by half in the past six months to 1 million, according to the latest data has been limited. released by the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU), led by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, and the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. However, the humanitarian situation remains fragile. An additional 1.7 million people who emerged from crisis in the past year are in a stressed food security situation, at risk of falling back FIGURES into crisis without continued support to meet basic needs and build up their livelihoods. # of people in 1.05m The acting Humanitarian Coordinator stated that aid workers need to continue helping humanitarian people who have lost everything to get back into a productive life so that they can cope emergency and with future shocks, thereby lessening their dependence on aid. -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

PROTECTION of CIVILIANS REPORT Building the Foundation for Peace, Security and Human Rights in Somalia

UNSOM UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN SOMALIA PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS REPORT Building the Foundation for Peace, Security and Human Rights in Somalia 1 JANUARY 2017 – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................7 Civilian Casualties Attributed to non-State Actors ....................................................................9 A. Al Shabaab .............................................................................................................................9 B. Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama ..........................................................................................................16 C. Clan Militia ..........................................................................................................................17 D. The Islamic State Affiliated Group ......................................................................................17 Civilian Casualties Attributed to State Actors and other Actors ............................................18 A. Somali National Army ...................................................................................................18 B. Somali Police Force .......................................................................................................21 C. The National Intelligence Security Agency -

Protection Cluster Update Weekly Report

Protection Cluster Update Funded by: The People of Japan Weeklyhttp://www.shabelle.net/article.php?id=4297 Report 9 th September 2011 European Commission IASC Somalia •Objective Protection Monitoring Network (PMN) Humanitarian Aid This update provides information on the protection environment in Somalia, including apparent violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law as reported during the last two weeks through the IASC Somalia Protection Cluster monitoring systems. Incidents mentioned in this report are not exhaustive. They are intended to highlight credible reports in order to inform and prompt programming and advocacy initiatives by the humanitarian community and national authorities. General Overview Attempts to improve ties between the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and the government of Puntland were initiated after both the TFG Prime Minister Sheikh Abdiweli Mohamed and the President, Sharif Sheikh Ahmed visited Garowe and met with Puntland government officials. Among other things, the two sides agreed to strengthen security cooperation, fight terrorism and promote and protect human rights in Puntland. However, it remains to be seen what effect the agreement may have on overarching protection concerns in Puntland with regards to ongoing clan conflicts, politically motivated killings, protection of IDPs and violations resulting from piracy-related crimes. 1 Despite the positive political developments, violence erupted in Gaalkacyo between the Puntland police and clan militias on 1 September and continued for three days. The violence resulted in a large number casualties and massive displacement within Gaalkacyo as many moved their families to safer areas. A report suggests that approximately 80% of the Gaalkacyo town population of 100,000 moved out to nearby villages.2 The split within Al Shabaab ranks which ultimately led to its general withdrawal from the capital Mogadishu continues to. -

F. List of Commitments/Contributions and Pledges to Projects In

Consolidated Appeal: Somalia 2012 List of commitments/contributions and pledges to projects listed to the Response Plan (Appeal launched on 14-December-2011) http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: ReportF) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Summary of Funding Outstanding Contributions USD Pledges USD Contributions sub total: 433,648,217 1,092,929 Contributions to CHF 89,438,817 0 sub total: Allocations out of plan -44,991,816 0 sub total: Carry-over sub total: 134,214,360 0 Appeal Total: 612,309,578 1,092,929 Contributions Donor Organization Project Description Cluster Funding Outstanding USD Pledges USD Allocation of unearmarked Food & Agriculture SOM-12/CSS/48315/R/ Food Security and Nutrition Analysis ENABLING 123,448 funds by FAO Organization of the United 123 Unit (FSNAU) PROGRAMMES Nations Allocation of unearmarked Food & Agriculture SOM-12/A/48362/R/123 Integrated approach to protecting the FOOD SECURITY 200,000 funds by FAO Organization of the United livelihood assets of pastoral Nations communities in Famine, Humanitarian Emergency and Acute Food and Livelihood Crisis in Somalia Allocation of unearmarked Food & Agriculture SOM-12/A/48384/R/123 Livelihood support for agropastoral FOOD SECURITY 200,000 funds by FAO Organization of the United communities in Famine, Nations Humanitarian Emergency and Acute Food and Livelihood crisis in Somalia Allocation of unearmarked United Nations Children's Fund SOM-12/SNYS/49534/R/ Humanitarian response CLUSTER NOT YET 2,099,958 funds by UNICEF -

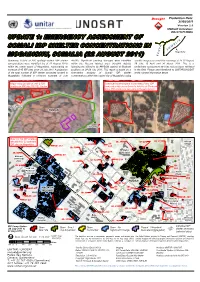

Drought Production Date: 31/08/2011 K E N Y a SO M a LI A

Drought Production Date: 31/08/2011 Version 2.0 !!+ UNOSAT Activation: DR20110714HOA SOMALIAF Mogadishu KENYA Summary: A total of 226 spatially distinct IDP shelter 41,000. Significant building damages were identified satellite imagery recorded the mornings of 21-22 August, concentrations were identified (as of 22 August 2011) within the Bacaad Market area (Yaqshid district) 28 July, 15 April and 30 March 2011. This is a within the urban extent of Mogadishu, representing an following the offensive by AMISOM against al Shabaab preliminary assessment and has not yet been validated increase of 45 IDP sites since 28 July 2011. A projection positions on 28-29 July 2011. This report is based on a in the field. Please send feedback to UNITAR/UNOSAT of the total number of IDP shelter structures located in time-series analysis of Somali IDP shelter at the contact information below. Mogadishu indicated a minimum estimate of over concentrations within the capital city of Mogadishu using Major camp growth of over 2,750 Continued north-eastern movement of new IDP shelters in IDP site (ID:115), Hodan camp sites into areas formerly-held by al Shabaab (here 250 shelters in two sites in Huriwa district) Digfer Hospital HODAN Taleh Village Over 18,400 IDP shelters Identified for 52 selected ID: 295 ID: 296 ID: 297 African ID: ID: IDP sites in Mogadishu ID: 213 Village 87 ID: 212 215 ID: 91 Digfer ID: 299 ID: 83 Hospital ID: 89 National ID: 115 University ID: 161 ID: 214 (frm) ID: 92 ID: 84 ID: Frm. US 250 Embassy Taleh Compound ID: 93 Village ID: ID: 249 -

Somalia, Grouped by Priority

Consolidated Appeal: Somalia 2012 List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 29-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R33) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD A - HIGH SOM-12/E/48177/R/ Emergency Education Response for IDPs AYUUB 1,274,921 1,070,918 0 0% 1,070,918 0 children through Integration in Lower 15231 Shabelle region SOM-12/F/48178/14852 Emergency Food Assistance for Those in HOD 299,223 299,223 0 0% 299,223 0 Humanitarian Emergency in Kismayo IDP Camps SOM-12/H/48255/R/ Emergency Nutrition Support for Children Mercy-USA for Aid 914,374 457,187 0 0% 457,187 0 and Pregnant and Lactating Mothers and Development 8396 through A Quality, Integrated Basic Nutrition Services Package (BNSP) SOM-12/H/48256/124 Emergency Outbreak preparedness and UNICEF 3,512,116 2,202,595 0 0% 2,202,595 0 response - Measles and Acute Watery Diarhoea (AWD) SOM-12/S-NF/48260/R/ Emergency project to distribute 25,000 SYPD 1,962,951 1,407,606 0 0% 1,407,606 0 NFI kits to drought- uprooted IDPs in Bay, 15101 Bakool and Middle Shabelle regions. SOM-12/ER/48261/8384 Emergency Response and Early Recovery PASOS 801,750 801,750 385,410 48% 416,340 0 Assistance in Burhakaba District of Bay Region of Somalia SOM-12/F/48264/R/ Emergency Response to increase access JCC 875,391 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 to food in order to save lives and 8380 livelihoods of , 21,000( 3,500 households)facing humanitarian emergency in Bu'ale and Sakow/salagle, Middle Jubba Region, through Cash for Work. -

Som Malia E Emerg Gency Y Wee Ekly H Health Upda

Somalia Emergency Weekly Health Update The Som alia emergency weekly health update aims to provide an overview of the health activities conducted by WHO and health partners in Somalia. It compiles health information including nine health events (epidemiological surveillance) reported in Somalia, information on ongoing conflicts in some regions of Somalia and health responses from partners. For further information please contact: Pieter Desloovere – WHO Communications Officer - [email protected] - T: +254 733 410 984 BULL ETIN HIGHLIGHTS Reporting dates 22 - 28 September 2012 (reflecting Epidemiological week 38) • Suspected cholera outbreaks have been reported in Hoosingow and Waraq villages in Badhaadhe district, Afmadow and Dobley towns in Afmadow district and Hagar district. A total of 14 samples of suspected cholera ca ses were collected from Hoosingow and Dobley town, and 12 of these 14 collected samples tested positive fo r cholera. IN FOCUS STORY: ©AVRO Explosion at village restaurant killing at least 18 people On 20 september 2012, an explosion occurred in Habarweyne district in Mogadishu, killing at least 18 people and injuring another 15 people. The explosion took place at night time near the Village restaurant, which is opposite the National Theatre and about one kilometre from the presidential palace. A lot of the casualties and injured people included media people working for SNT (Somali National Television) and goverment officials. At the time of the explosion, a lot of people were present in the restaurant as it was the time for taking tea. The Aamin Ambulance Services (AAS) were alerted immediatelly and rushed to the place of the accident. -

Black Landscape Copy

in the line of fire SOMALIA’S CHILDREN uNDER AttACk Amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal Declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. first published in 2011 by Amnesty international ltd Peter Benenson house 1 easton Street london WC1X 0DW united kingdom © Amnesty international 2011 index: Afr 52/001/2011 english original language: english Printed by Amnesty international, international Secretariat, united kingdom All rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: Children play in ifo refugee camp as the sun goes down, Dadaab, kenya, December 2008. the camps at Dadaab are home to more than 200,000 Somali refugees. © unhCr/e. hockstein amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................3 2. Background..............................................................................................................6 Domestic parties to the conflict...................................................................................7 3. -

The Case of Marine Environmental Management in Somalia

The Stability/Sustainability Dynamics: The Case of Marine Environmental Management in Somalia QASIM HERSI FARAH A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillments for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Environmental Studies York University Toronto, Ontario October 2016 QASIM HERSI FARAH, 2016 Abstract Since January 1991, Somalia has been a war-torn society without law and order machinery. After a decade of chaos, in January 2001, an interim government formed in Djibouti was brought to Mogadishu, albeit it failed to function. Two similar others followed; one in 2004 and the other in 2007. In 2012, a federal government was elected by 275 members of parliament, but it is yet to govern most of the country’s regions. Consequently, over 25 years, there has been sociopolitical and economic instability which jeopardised Somalia’s environment and security (land and marine). Now, who are the actors of socio-political and economic instability, and can marine sustainability be achieved in the absence of stability? This doctoral study identifies, defines, examines and analyzes each of the state and non- state actors/networks operating in Somalia, at the international, regional, national, provincial, and local levels. I investigated who are they and what are their backgrounds/origins? What are their objectives and strategies? What are their capacities and economic status? What are their motives and manoeuvres? and what are their internal and external relationships? I categorised each one of them based on these scales: instability, potential stability or stability. I adopted a multi-dimensional approach which aims at tackling both marine environmental degradation and insecurity in the Somali basin, while establishing a community-based policy as a milestone for the formulation of a national/provincial policy.