Healthy Communities; Low Impact Development & Green

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

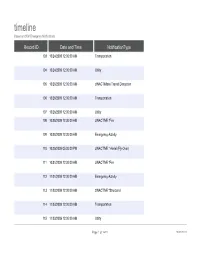

Timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications

timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Record ID Date and Time NotificationType 103 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 104 10/24/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 105 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIMass Transit Disruption 106 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 107 10/26/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 108 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 109 10/28/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 110 10/29/2009 05:00:00 PM zINACTIVE * Aerial (Fly-Over) 111 10/31/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Fire 112 11/01/2009 12:00:00 AM Emergency Activity 113 11/02/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Structural 114 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Transportation 115 11/03/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility Page 1 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Notification Title [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Major Gas Explosion 32-25 Leavitt St. [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Page 2 of 1419 10/02/2021 timeline Based on OEM Emergency Notifications Email Body Notification 1 issued on 10/24/09 at 11:15 AM. Emergency personnel are on the scene of a motor vehicle accident involving FDNY apparatus on Ashford Street and Hegeman Avenue in Brooklyn. Ashford St is closed between New Lots Ave and Linden Blvd. Hegeman Ave is closed from Warwick St to Cleveland St. Notification 1 issued 10/24/2009 at 6:30 AM. Emergency personnel are on scene at a water main break in the Fresh Meadows section of Queens. -

Mta Property Listing for Nys Reporting

3/31/2021 3:48 PM MTA PROPERTY LISTING FOR NYS REPORTING COUNTY SECTN BLOCKNO LOTNO Property_Code PROPERTYNAME PROPERTYADDDRESS AGENCY LINE PROPERTYTYPE limaster LIRR Customer Abstract Property LIRR Customer Abstract Property LIR Main Line Station Bronx bbl05200 Bronx Whitestone Bridge Hutchson River parkway BT Block/Lot Bridge Bronx 9 mha04650 ROW b 125th & Melrose XXX St MN Harlem ROW Bronx 9 mha06600 ROW b 125th & Melrose Milepost 5,Sta-Mon# 31.5 MN Harlem ROW Bronx 12 mha09500 FORDHAM STATION Fordham Rd (Fordham U) MN Harlem Station Bronx mhu00343 Perm E'ment at Yankee Stadium Sta-mon 30.5 MN Hudson Payable Easement Bronx mhu06251 Spuyten Duyvil Substation Sta-Mon# 68.5 MN Hudson Payable Easement Bronx 19 mhu06301 Parking at Riverdale Milepost 12 , Sta-Mon# 68.5 MN Hudson Parking Bronx tbl03600 Unionport Shop Unionport Rd. NYCT White Plains Road Shop Bronx tbl65340 Con Edison Ducts East 174 St NYCT Block/Lot Ducts Bronx tbw32500 231ST 231 St-Broadway NYCT Broadway/7th Avenue Station Bronx tbw32600 238 ST 238 St-Broadway NYCT Broadway/7th Avenue Station Bronx tbw32700 242 ST 242 St-Van Cortlandt Pk NYCT Broadway/7th Avenue Station Bronx tco21000 161 ST Yankee Stadium 161 St/River Ave NYCT Concourse Station Bronx tco21100 167 ST 167 St/Grand Concourse NYCT Concourse Station Bronx tco21200 170 ST 170 St/Grand Concourse NYCT Concourse Station Bronx tco21300 174 175 STs 174-175 Sts/Grand Concourse NYCT Concourse Station Bronx tco21400 TREMONT AVE Tremont Ave/Grand Concourse NYCT Concourse Station Bronx tco21500 182 183 STs 183 St/Grand -

ORDER Granting 20 Motion for Summary Judgment. Ordered By

Peterson v. Long Island Railroad Company Doc. 34 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------x MICHAEL K. PETERSON, Plaintiff, Memorandum and Order 10 Civ. 480 - against - LONG ISLAND RAILROAD COMPANY Defendant. ------------------------------------------------------x GLASSER, United States District Judge: Plaintiff Michael K. Peterson (“Peterson” or “plaintiff”) brought this action against his former employer, Long Island Rail Road Company (“LIRR” or “defendant”), alleging retaliation in violation of the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (“FMLA”), 29 U.S.C. §§ 2601 et seq., and race-based employment discrimination in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“Title VII”), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., The New York State Human Rights Law (“NYSHRL”), N.Y. Exec. Law § 296, et seq. (McKinney 2010), and the New York City Human Rights Law (“NYCHRL”), N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-502. Peterson also alleges intentional infliction of emotional distress under New York State Law. Before the Court is defendant’s motion for summary judgment, pursuant to Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. For the reasons set forth below, defendant’s motion is GRANTED. BACKGROUND The following facts are undisputed unless otherwise noted.1 Peterson, an African-American male, worked as an Electrician for the LIRR in the Department of 1 Defendant urges the Court to deem admitted all statements contained in Defendant’s Statement Pursuant to Local Rule 56.1 (“Def.’s R. 56.1”) on the grounds that Plaintiff’s Counter- 1 Dockets.Justia.com Engineering for approximately 11 years. He was represented by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 589 (“IBEW”), pursuant to a Collective Bargaining Agreement between LIRR and IBEW. -

Legislative and Community Input

Metropolitan Transportation Authority Office of Legislative and Community Input Compilation of Concerns, Comments and Recommendations Pursuant to Chapter 25 of the Laws of 2009 August 16, 2009 through February 10, 2010 Senate, Legislator's Name of Agency Request/Concern/ Close Out Assembly or Name (none if Legislator's or Date Received MTA Response or Proactive Notification or Briefing Tracking Recommendation Expressed Date PCAC PCAC) PCAC Contact Noise complaint on behalf of constituent regarding Henry Hudson B&T905 Assembly Dinowitz, Jeffrey 06/01/09 Explanation of noise given and promise to monitor going forward. 06/01/09 construction. Sen. Klein's office called the Bronx Whitestone Bridge to clarify ownership info on Ferry Point Park Service Road. He was referred to B&T906 Senate Klein, Jeffrey John Doyle 06/10/09 Property under NYC DOT not B&T. 06/10/09 NYC DOT Office of the Bronx Borough Commissioner, as the road is not B&T property. LIRR1123 Senate Padavan, Frank 06/18/09 Constituent Concerns regarding Broadway Station Information provided 07/20/09 Constituent concerns regarding pedestrian overpass at Bay Shore Information provided regarding inspection and schedule of repairs and LIRR1117 Senate Johnson, Owen 06/22/09 08/04/09 Station description of work being done NYCT provided a thorough review of the F line report and presented the MTAHQ1027 Senate Squadron, Daniel Raskin, John 6/23/2009 Requested a comprehensive study on the F line. 10/08/09 findings to Senator Squadron and his staff. Senator informed of investigation and review of situation. Constituent sent LIRR1120 Senate Johnson, Owen 06/26/09 Constituent inquiry regarding retiree health benefit issue 07/16/09 letter. -

OEM Emergency Notifications

OEM Emergency Notifications Record ID Date and Time NotificationType 1 05/22/2009 03:23:00 PM Utility 2 05/22/2009 05:56:00 PM Utility 3 05/29/2009 07:20:00 PM School Notification 4 05/30/2009 05:00:00 PM zINACTIVE *Drills / Exercises 5 06/01/2009 05:20:00 PM School Notification 6 06/02/2009 04:30:00 PM School Notification 7 06/03/2009 06:45:00 PM zINACTIVE *Fire 8 06/09/2009 02:53:00 PM zINACTIVE *Drills / Exercises 9 06/14/2009 01:25:00 PM Utility 10 06/21/2009 12:00:00 AM zINACTIVE *Structural 11 06/21/2009 03:20:00 PM zINACTIVE *Structural 12 06/25/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility 13 06/25/2009 12:00:00 AM Utility Page 1 of 1422 09/28/2021 OEM Emergency Notifications Notification Title Blank [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Page 2 of 1422 09/28/2021 OEM Emergency Notifications Email Body This is a message from Notify NYC. Notification 2 issued 5/22/09 at 3:23 PM. Co-op City in the Bronx is experiencing a power outage. Emergency personnel are on the scene and are attempting to reset the system. The estimate time of power restoration is 1 hour. This is a message from Notify NYC. Notification 3 issued 5-22-09 at 5:56pm. Power has been restored to the entire CO-OP City complex. This is a message from Notify NYC. Notification 1 issued 5/29/09 at 7:20 PM.