Evaluating the Impact of Cheshire East Emotionally Health Schools Pilot Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Impact of the Cheshire East Emotionally Health Schools Pilot Project

Evaluating the impact of the Cheshire East Emotionally Health Schools Pilot Project Research Report April 2017 1 This study was carried out by the University of Salford CYP@Salford research group on behalf of Cheshire East Council. The study was funded by Cheshire East Council. The purpose of the study was to identify the outcomes for pupils and staff following the delivery of the Emotional Healthy Schools pilot project into six secondary schools. The research team acknowledges the support and time given by the staff and pupils of the pilot schools and the EHS project team to make this research possible. 2 CYP@Salford Improving Outcomes for Children, Young People and Families http://www.salford.ac.uk/nmsw/research/children,-young-people-and-families Our research spans health, social care and education, and focuses on enhancing services, improving outcomes and evidencing impacts on children and families. The research group works closely with colleagues in the NHS, Local Authorities, the Third Sector, and national networks. We have research links with international partners in the Nordic countries, the Middle East, the Far East, Europe and Australia. Celeste Foster Principal Investigator Dr Gillian Rayner Dr Shelly Allen CYP@Salford School of Nursing, Midwifery, Social Work and Social Sciences Mary Seacole Building University of Salford SALFORD M6 6PU 3 Contents CYP@Salford ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Tables and Figures ............................................................................................................................. -

Admissions Policy 2021 and Beyond

Admissions Policy 2021 and beyond DISTRIBUTION This is a Trust-wide policy and applies to the Trust. DOCUMENT ID FT-AM006 Admissions Policy AUTHOR Trust VERSION 3.0 RATIFIED BY THE DIRECTORS OF THE 15 July 2021 FALLIBROOME TRUST POLICY REVIEW DATE In line with changes to legislation and best practice POLICY REQUIREMENT STATUTORY The Fallibroome Trust, Priory Lane, Macclesfield, Cheshire, SK10 4AF Telephone: +44 (0) 1625 827 898 | Email: [email protected] | Web: www.fallibroometrust.org.uk The Fallibroome Trust (Company number: 07346144). A company incorporated as private limited by guarantee. Registered Office situated in England and Wales Admissions Policy FT-AM006 | 2.0 | 2021-22 Page 2 of 24 Admissions Policy FT-AM006 | 2.0 | 2021-22 CONTENTS Statement of intent .............................................................................................................. 4 Legal framework .................................................................................................................. 5 Roles and responsibilities .................................................................................................... 6 Admissions .......................................................................................................................... 7 Admissions appeals ........................................................................................................... 12 Appendix A ....................................................................................................................... -

The Macclesfield Academy Park Lane, Macclesfield, Cheshire, SK11 8JR

School report The Macclesfield Academy Park Lane, Macclesfield, Cheshire, SK11 8JR Inspection dates 21–22 May 2013 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected Overall effectiveness This inspection: Requires improvement 3 Achievement of pupils Requires improvement 3 Quality of teaching Requires improvement 3 Behaviour and safety of pupils Good 2 Leadership and management Good 2 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a school that requires improvement. It is not good because Although significant improvements have been Teaching is not consistently good across the made since the academy opened under two majority of subjects, and there are insufficient years ago, students’ overall achievement is lessons in which it is outstanding. not yet good. Some teachers take too little account of Some lower-ability students and those students’ prior knowledge when planning tasks, supported through ‘school action’ do not so that it is not built on sufficiently well to always make sufficient progress to enable improve students’ understanding and speed up them to reach their full potential. their learning. The proportion of higher-ability students reaching the highest A* to A grades at GCSE, for example in English and mathematics, is below average. The school has the following strengths The headteacher, senior leaders and Students behave well and feel safe. They are governors have set an ambitious agenda for proud of their academy and parents are improvement underpinned by challenging overwhelmingly supportive of what it has to targets. offer. Many parents praise the excellent The academy demonstrated one of the pastoral care and support for their children and fastest rates of improvement in students’ are appreciative of how this is given equal attainment of any school in the country in emphasis to academic targets. -

Insert Title Text Here

Post 16 Education Travel Policy Statement Cheshire East Council 1 September 2018 www.cheshireeast.gov.uk OFFICIAL Document summary This document provides travel information for young people of sixth form age1 and adults aged 19 and over (including those with an Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan) in education and training2. Contents Section Title Page 1. Summary and Objectives 3 2. Post 16 Transport Duty 4 3. Details of Travel Assistance and Eligibility 5 4. Reviewing Eligibility 10 5. General Details 10 6. General Information on Travel Support 11 7. Support for Students reaching 19 14 8. Mobility/Independence Training 14 9. When to Apply for Support 15 10. Help Outside the Local Authority 15 11. Help for Establishments Outside Daily Travelling 15 12. ComplaintsDistance 16 Appendix 1 List of post 16 education providers in the area 17 Other related education travel policies: • Compulsory School Age Education Travel Policy • Education Travel Payments Policy • Education Travel Behaviour Code • Education Travel Appeals and Complaints Policy • Sustainable Modes of Travel Strategy 1 Section 508H and Section 509AB(5). 2 Section 509AC(1) of the Education Act 1996 defines persons of sixth form age for the purposes of the sixth form transport duty. OFFICIAL 2 1. Summary of Policy Statement and Objective 1.1 This policy statement provides information for Cheshire East students and their parents3 about the travel assistance available to them when continuing in education or training beyond compulsory school age4. It relates to Post 16 learners who are aged 16-18 years of age including those with special educational needs and disabilities aged 19 years of age including those with special educational needs and disabilities who started a course before their 19th birthday and who continue to attend that course Adults under 25 years of age, including those with special educational needs and disabilities, with or without an Education and Health Care Plan (EHCP) who wish to attend an educational course. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Meeting : Projects & Finance Committee

Meeting : Projects & Finance Committee. Date : 11.3.19 Time: 9.30am Location: Congleton Town Hall, Spencer Suite In attendance: S.Foster (Chair) M.Smith ,J.MacArthur, , J.Money , D.McGifford ,S.Munro, G.Williams, V.Cutcliffe. Guest Item Agenda Item / discussion Action / comment 1. Welcome and Introduction. Apologies:- Meeting chaired by S.Foster. P.Aston. 2. Matter Arising from the last meeting (11.3.19) . Accepted as a true record of the meeting. The action points will be picked up as we work through the projects. 3. Partnership Executive Make up. Following recent political, local trust and community changes a review of membership was discussed. It was agreed that MS would write to Bob Edwards to see if he wished to stay with The MS write to Bob Edwards. Partnership. JM to discuss with David Daniel his position. JM contact D.Daniel The new representative for The Inclosure Trust (replacing John Beardmore) is Janet JM let MS have J.Goodier Goodier, Jo to get me her contact details. contact details. P.Bates, role is no longer applicable (Business/Marketing) Two new Town Council to be confirmed after Mayor making. SF / MS to present an overview of The Partnership at the next Full Council Meeting. SF / MS present full council. 4. Project updates Dementia Friendly Town. New target for Dementia Friends set at 1000, currently at 721. 28 organisations / businesses are involved. We have 14 businesses that we are currently working with to improve their physical environment. Presentation on the Dementia Buddy Scheme took place on 23rd April, around 25 attendees. -

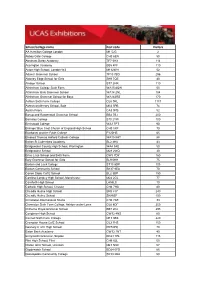

School/College Name Postcode Visitors

School/college name Postcode Visitors Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 45 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 100 Accrington & Rossendale College BB5 2AW 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 116 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 309 Alder Grange Community & Technology School BB4 8HW 99 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 126 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 60 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 170 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 160 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1223 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 56 Audenshaw School M34 5NB 55 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 54 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Baines School FY6 8BE 35 Barnsley College S70 2YW 153 Benton Park School LS19 6LX 125 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 105 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 95 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY2 0HB 94 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 80 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 55 Bradford College BD7 1AY 40 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 40 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 33 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 150 Burnley College BB12 0AN 500 Bury College BL9 0DB 534 Bury Grammar School Boys BL9 0HN 80 Buxton and Leek College SK17 6RY 100 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 90 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 69 Carnforth High School LA59LS 35 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 84 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 372 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 54 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 334 Congleton High School CW12 4NS -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors AA Hamilton College London M1 5JG 2 Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 50 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 110 Acton High School, London W3 M112WH 52 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 296 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 110 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 55 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 184 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 170 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1117 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 74 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 52 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Barnsley College S70 2YW 100 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 90 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 70 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY20HB 65 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 88 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 43 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 50 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 30 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 160 Bury Grammar School for Girls BL9 0HH 75 Buxton and Leek College ST13 6DP 103 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 70 Canon Slade Cof E School BL2 3BP 150 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 77 Carnforth High School LA59LS 10 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 80 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 240 Cheadle Hulme School SK86EF 150 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 33 Clarendon Sixth Form College, Ashton-under-Lyme OL6 6DF 250 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 295 Congleton High School CW12 4NS 60 Connell Sixth Form College M11 3BS 220 Crompton House -

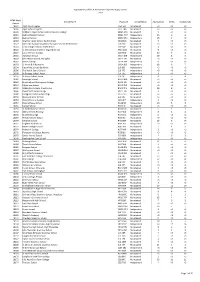

2013 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2013 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 6 4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 9 <3 <3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 5 4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 18 6 6 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 8 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 18 9 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 9 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 8 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon -

New Year: New Resolutions

NEW YEAR: NEW RESOLUTIONS Welcome to our first Newsletter has been to develop our students for other activities and get a healthy of 2019. At the start of a new year, as independent learners. This is an 8 hours’ sleep! our thoughts inevitably turn to new ongoing challenge for some who Whatever your resolutions, I wish you resolutions, and in assembly on the instinctively ask for a teacher’s all a healthy and happy New Year. first day of term Mr Nicholson and I help before exhausting all other shared the magic numbers behind available strategies. Our approach is With every best wish! our resolutions with Year 11. For Mr summed up in the phrase 3 before Nicholson, the magic number was 5 me, which represents our expectation as he tries to curb his chocolate habit that students will first, think for and increase his intake of fruit and themselves, secondly, consult their vegetables. For me the number was learning resources and, thirdly, discuss 10000 as, armed with my Christmas with each other, before asking for help. present fit bit, and in fierce competition RICHARD HEDGE The third number (and one which I with my daughters, I try to increase the Headteacher shared with the Year 11 students in number of steps I walk each day. their first assembly) applies to all of For our students I want to suggest those students who are preparing three other numbers that could for external exams. The number is 2 usefully underpin resolutions for them because we can guarantee that all at the start of a new year. -

9.30 Am Meeting

MEETING OF THE CORPORATION OF MACCLESFIELD COLLEGE TUESDAY 6 OCTOBER 2020 – 9.30 AM MEETING TOOK PLACE VIA ZOOM PART I Clerk: Mrs R Clare Attendance: M Wright (Chair), C Trasler, P Newell, A Sutcliffe, N Schofield, K Williams, J Walters, N Mannion, S Musgrave, R Kay In L French, L Reed, S Gardiner attendance: Apologies: M Sharples, E Kennedy MINUTES Actions 4/20 The Macclesfield Academy AS/RH RK requested a formal paper on the timeline of the process, options and timescales and a thorough report on this matter for the next Corporation meeting. 6/20 Quality and Curriculum LR A governor questioned the percentages reported in the table. LR will check the figures provided by MIS. LR stated that this might be due to the coding from MIS but the columns should add up to 100% so required a further review. 7/20 Business LF ELT are holding a strategic day offsite to review the finance and strategic position in more detail and contingencies will be shared at the December Corporation meeting including assumptions and impact on the budget. 7/20 Business (Enrolment update) LF LF explained that apprenticeship numbers would be shared at the next meeting after the new starts at the end of October. 7/20 Business (Enrolment update) LF Numbers of Levy and Non-Levy to be shared at the next meeting. Corporation Minutes 6 October 2020 1 Item Title 28/20 Welcome and Apologies for Absence MW acted as Chair for the meeting in the absence of MS. MW welcomed Members to the first meeting of the academic year and confirmed apologies for absence.