Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armand Lavergne L'œuvre DES TRACTS (Directeur: R

No 190 Un Patriote Armand LaVergne L'ŒUVRE DES TRACTS (Directeur: R. P. ARCHAMBAULT, S. J.) Publie chaque mois une brochure sur des sujets variés et instructifs * 1. L'Instruction obligatoire Sir Lomer GOUIN, Juge TELLIER * 2. L'École obligatoire Mgr PAQUET 3. Le Premier Patron du Canada R. P. LECOMPTE, S. J. 4. Le Bon Journal R. P. MARION, O. P. * 5. La Fête du Sacré Cœur R. P. ARCHAMBAULT, S. J. * 6. Les Retraites Jermèes au Canada .... R. P. LECOMPTE, S. J. * 7. Le Uocleur Painchaud C.-J. MAGNAN * 8. L'Eglise et l'Organisation ouvrière . R. P. ARCHAMBAULT, S. J. * y. Police! Police! A l'école, les enjants! . B. P. 1U. Le Mouvement ouvrier au Canada . Umer HÉROUX 11. L'École canadienne-française R. P. Adélard DUGRÉ, S. J. 12. Les Familles au Sacré Cœur R. P. ARCHAMBAULT, S. J. *13. Le Cinéma corrupteur Euclide LEFEBVRE 14. La Première Semaine sociale du Canada. R. P. ARCHAMBAULT, S. J. lb. Sainte Jeanne d'Arc R. P. CHOSSEGROS, S. J. *16. Appel aux ouvriers Georges HOGUE 17. Notre-Dame de Liesse R. P. LECOMPTE, S. J. Ici. Les Conditions religieuses de notre société. Le cardinal BEGIN la. Sainte Marguerite-Marie Une RELIGIEUSE 2u. La Y. M. C. A R. P. LECOMPTE. S. J. 21. La Propagation de la Foi BENOÎT XV 22. L'Aide aux œuvres catholiques R. P. Adélard DUGRÉ, S. J. *23. La Vénérable Marguerite Bourgeoys. R. P. JOYAL, O. M. 1. 24. La Formation des Élites Général DE CASTELNAU *25. L'Ordre séraphique Fr. MARIE-RAYMOND, O. -

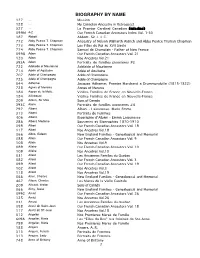

Biography by Name 127

BIOGRAPHY BY NAME 127 ... Missing 128 ... My Canadian Ancestry in Retrospect 327 ... Le Premier Cardinal Canadien (missing) 099M A-Z Our French Canadian Ancestors Index Vol. 1-30 187 Abbott Abbott, Sir J. J. C. 772 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Ancestry of Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich and Abby Pearce Truman Chapman 773 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Les Filles du Roi au XVII Siecle 774 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Samuel de Champlain - Father of New France 099B Adam Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 21 120 Adam Nos Ancetres Vol.21 393A Adam Portraits de familles pionnieres #2 722 Adelaide of Maurienne Adelaide of Maurienne 714 Adele of Aquitaine Adele of Aquitaine 707 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 725 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 044 Adhemar Jacques Adhemar, Premier Marchand a Drummondville (1815-1822) 728 Agnes of Merania Agnes of Merania 184 Aigron de la Motte Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 184 Ailleboust Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 209 Aitken, Sir Max Sons of Canada 393C Alarie Portraits de familles pionnieres #4 292 Albani Albani - Lajeunesse, Marie Emma 313 Albani Portraits de Femmes 406 Albani Biographie d'Albani - Emma Lajeunesse 286 Albani, Madame Souvenirs et Biographies 1870-1910 098 Albert Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 18 117 Albert Nos Ancetres Vol.18 066 Albro, Gideon New England Families - Genealogical and Memorial 088 Allain Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 9 108 Allain Nos Ancetres Vol.9 089 Allaire Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 10 109 Allaire Nos Ancetres Vol.10 031 Allard Les Anciennes Familles du Quebec 082 Allard Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. -

Bibliographie 1

Bibliographie 1. SOURCES L’Action. Entièrement dépouillé (1911-1916). Archives de l’Archevêché de Montréal (Montréal). Fonds Journaux, années 1911, 1912, 1913, 1914, 1915 et 1916. Archives nationales du Canada (Ottawa). Fonds Wilfrid Laurier (MG-26J), correspondance (série A), pièces 87030 a-b-c-d. Le Devoir. Consulté pour l’année 1910. Fournier, Jules. Anthologie des poètes canadiens. Montréal, Granger Frères Limitée, 1920. 309 pages. Préface par Olivar Asselin. Rééditions en 1933 et 1934 remaniées par Thérèse Fournier. Fournier, Jules. La cité des livres. s. l., s. d.. 46 pages. Fournier, Jules. Mon encrier. Montréal, 1922. (Recueil d'articles colligés par Thérèse Fournier). Préface par Olivar Asselin. Réédité et augmenté en 1965 par Fides. Ajout d'une courte biographie par Adrien Thério. Fournier, Jules. Souvenirs de prison. s. l., 1910. 63 pages. Le Nationaliste. Années dépouillées: 1904 à 1910. La Patrie. Consulté pour l’année 1910. La Revue canadienne. Consultée pour les années 1906 et 1907. 2. ÉTUDES PORTANT SUR JULES FOURNIER Bastien, Hermas. “ Jules Fournier, journaliste et fine lame (1884-1918) ”, Qui? Art, musique littérature. Vol. 5, no 1, septembre 1953, pp. 3-24. Bérubé, Renald. “ Jules Fournier : trouver le mot de la situation ” dans Paul Wyczynski dir., L'essai et la prose d'idée au Québec. Montréal, Fides, 1985. Duhamel, Roger. “ Jules Fournier ”. Cahiers de l'Académie canadienne-française, no 7, 1963, pp. 251-259. Imbert, Patrick. “ "Mon encrier" de Jules Fournier ou l'ironie au service de la patrie ”, Lettres Québécoises. 2, mai 1976, pp. 24-25. Lapierre, Juliette. Notes bio-bibliographiques sur Jules Fournier journaliste. Mémoire de l'École de bibliothéconomie, Université de Montréal, 1948. -

The Municipal Reform Movement in Montreal, 1886-1914. Miche A

The Municipal Reform Movement in Montreal, 1886-1914. Miche LIBRARIES » A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Ottawa. 1972. Michel Gauvin, Ottawa 1972. UMI Number: EC55653 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55653 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis will prove that the Montreal reform movement arose out of a desire of the richer wards to control municipal politics. The poorer wards received most of the public works because they were organized into a political machine. Calling for an end to dishonesty and extravagance, the reform movement took on a party form. However after the leader of the machine retired from municipal politics, the movement lost its momentum. The reform movement eventually became identified as an anti-trust movement. The gas, electricity, and tramway utilities had usually obtained any contracts they wished, but the reformers put an end to this. -

Dissenting in the First World War: Henri Bourassa and Transnational Resistance to War Geoff Keelan

Document generated on 09/26/2021 6:07 p.m. Cahiers d'histoire Dissenting in the First World War: Henri Bourassa and Transnational Resistance to War Geoff Keelan Paix, pacifisme et dissidence en temps de guerre, XX-XXIe siècles Article abstract Volume 35, Number 2, Spring 2018 This article discusses the connection between French Canadian nationalist, the journalist Henri Bourassa, and other international voices that opposed the First URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1047868ar World War. It examines common ideas found in Bourassa’s writing and the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1047868ar writing of the Union of Democratic Control in Britain and the position of Pope Benedict XV about the war’s consequences, militarism and the international See table of contents system. This article argues that Bourassa’s role as a Canadian dissenter must also be understood as part of a larger transnational reaction to the war that communicated similar solutions to the problems presented by the war. Publisher(s) Cahiers d'histoire ISSN 0712-2330 (print) 1929-610X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Keelan, G. (2018). Dissenting in the First World War: Henri Bourassa and Transnational Resistance to War. Cahiers d'histoire, 35(2), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.7202/1047868ar Tous droits réservés © Cahiers d'histoire, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Dagenais, Michèle, Irene Maver, and Pierre-Yves Saunier

Document generated on 09/25/2021 12:17 a.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Dagenais, Michèle, Irene Maver, and Pierre-Yves Saunier. Municipal Services and Employees in the Modern City: New Historic Approaches. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2003. Pp. xii, 238. US$84.95 (hardcover) Caroline Andrew Volume 33, Number 1, Fall 2004 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015682ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015682ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Andrew, C. (2004). Review of [Dagenais, Michèle, Irene Maver, and Pierre-Yves Saunier. Municipal Services and Employees in the Modern City: New Historic Approaches. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2003. Pp. xii, 238. US$84.95 (hardcover)]. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 33(1), 60–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015682ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 2004 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Book Reviews / Comptes rendus While such an analysis would have required some different Dagenais, Michèle, Irene Maver, and Pîerre-Yves Saunier. -

History of Quebec. Cleophas Edouard Leclerc

834 HISTORY OF QUEBEC. as President of the Quebec Association of Architects, which post he now fills with much acceptability. To !?how he has a comprehensive knowledge of the principles and details of building construction and architecture, it is sufficient to enumerate the following magnificent buildings he has de- signed in Montreal, which stand for the beautification of the city, namely, the Board of Trade Building, Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, Olivet Baptist Church, the new Medical Building of McGill University, and the Children's Memorial Hospital, now in course of construction. Mr. Brown has also constructed several large manufacturing and com- mercial establishments, among which may be mentioned the following plants: The Standard Shirt Company, Southam Building on Alexander Street, Jenkins Bros., Limited, and the Canadian Spool Cotton Company at Maisonneuve, the latter being the Canadian business of the firm of J. & P. Coates, of Paisley, Scotland. Mr. Brown is a member of the Architectural League of New York and a member of the Montreal Board of Trade. Both his public and private life have been characterized by the utmost fidelity of duty, and he stands as a high type of honorable citizenship and straight- forward manhood, enjoying the confidence and winning the respect of all with whom he has been brought in contact in business life. In 1900 Mr. Brown married Harriet Fairbairn Eobb, second daughter of William Robb, City Treasurer, Montreal. He is a member of the Canada Club, the Manitou Club, the Beaconsfield Golf Club, and the Royal St. Lawrence Yacht Club. CLEOPHAS EDOUARD LECLERC. Cleophas Edouard Leclerc, Notary and Justice of the Peace, Montreal, has the distinction of being a direct descendant of Abraham Martin, the of Scottish pilot and historical character after whom the Plains Abraham at Quebec were named. -

Quality Journalism: How Montreal's Quality Dailies

Quality Journalism: How Montreal’s Quality Dailies Presented the News During the First World War by Gregory Marchand A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History Joint-Masters Program University of Manitoba/ University of Winnipeg Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2014 by Gregory Marchand Marchand i Abstract A careful examination of reporting during the First World War by Montreal’s two most respected daily newspapers shows that these newspapers articulated divergent messages about the war and domestic events. Each newspaper had its own political affiliations, and even though they were not always apparent, they were always present, influencing the ways in which each paper approached the war. Each paper’s editorial staff had previously tailored their output to what they perceived to be the tastes and interests of their middle class and elite readerships. This thesis argues that during the First World War, Le Devoir refused to be limited by the traditional impassive reporting style of Montreal’s managerial class newspapers, but the Montreal Gazette did not. Where Le Devoir became more defiant and aggressive in its defence of Francophone rights, the Gazette managed to appear more detached even as it reported the same events. This divergence is important because it represents a larger pattern of wartime change taking place as quality dailies gambled their reputations on the ideals of their owners and editors. Each newspaper carefully constructed their attempts to influence public opinion, but where Le Devoir was responding to what it considered a crisis, the Gazette’s interests and alliances mandated loyalty and a calmer tone. -

L'hebdomadaire La Renaissance (Juin-Décembre 1935), La Dernière a Venture D'olivar Asselin Dans La Presse Montréalaise

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL L'HEBDOMADAIRE LA RENAISSANCE (JUIN-DÉCEMBRE 1935), LA DERNIÈRE A VENTURE D'OLIVAR ASSELIN DANS LA PRESSE MONTRÉALAISE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN HISTOIRE PAR MAXIME TROTTIER JUILLET 2019 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.10-2015). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens d'abord.à remercier ma directrice, Dominique Marquis, d'avoir découvert le corpus de La Renaissance qui hibernait gentiment aux archives de l'UQÀM et de me Pavoir proposé. -

La Perspective Nationaliste D'henri Bourassa, 1896-1914 Joseph Levitt

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 12:57 Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française La perspective nationaliste d'Henri Bourassa, 1896-1914 Joseph Levitt Volume 22, numéro 4, mars 1969 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/302828ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/302828ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Institut d'histoire de l'Amérique française ISSN 0035-2357 (imprimé) 1492-1383 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Levitt, J. (1969). La perspective nationaliste d'Henri Bourassa, 1896-1914. Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 22(4), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.7202/302828ar Tous droits réservés © Institut d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 1969 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Joseph Levitt LA PERSPECTIVE NATIONALISTE D'HENRI BOURASSA 1896-1914 Richard Jones Commentaire 568 REVUE D'HISTOIRE DE L'AMÉRIQUE FRANÇAISE Joseph Levitt Ph.D. de l'Université de Toronto, 1966. Assistant-professeur à l'Université d'Ottawa. A paraître : The Social Program of the Nationalists of Quebec 1900-1914, thèse de Ph.D. qui sera publiée aux Presses de l'Université d'Ottawa sous le titre: Henri Bourassa and the Golden CaIf. -

Henri Bourassa and Conscription: Traitor Or Saviour?1 Pa C-009092

HISTORY HENRI BOURASSA AND CONSCRIPTION: TRAITOR OR SAVIOUR?1 PA C-009092 Portrait of Henri Bourassa in July 1917. by Béatrice Richard he conscription crisis exposed a wide Ontario’s Prussians gulf in Canadian society between 1916 and 1918. During that period, Henri y 1916, voluntary recruitment was yielding fewer Bourassa became, through the force of Band fewer enlistments. Up to that time, the majority his personality, the natural leader of all of volunteers had come from English Canada, and TFrench Canadians opposed to compulsory military service. anglophones resented being bled white while French Bourassa, a grandson of the patriote Louis-Joseph Canadians were seen to be sparing their own sons. Papineau, was the founder and editor of the independent The proponents of conscription argued that compulsory daily Le Devoir, a former Member of Parliament, and service would bring order and equality to recruitment.5 a formidable polemicist. He believed that the forced Prime Minister Robert Borden announced, on 17 May “militarization” of the Dominion was only the first 1917, the creation of a system of “selective, that is stage of an apocalyptic “imperialist revolution.” Needless to say gradual conscription, with men being divided to say, these pronouncements were seen as provocations into a number of classes called up as needed.”6 Despite at a time when thousands of Canadians were dying demonstrations involving thousands of opponents in the on the battlefields of the Western Front. The popular streets of Montreal, the Military Service Bill received English language press never missed an opportunity third reading on 24 July 1917, with a majority of 58 votes. -

Jules Fournier 1884-1918

Jules Fournier 1884-1918 Jules Fournier passa dans le ciel littéraire du Québec comme une météore : né à Coteau-du- Lac, comté de Soulanges, en 1884, dans une famille d’agriculteurs, il meurt de la grippe espagnole en 1918, à Ottawa. Dans ces 33 années et quelque, il a circulé dans d’autres sociétés, interpellé son milieu canadien-français, jugé très sévèrement la médiocrité de la culture et des mœurs qui l’entouraient, dénoncé la corruption politique, initié des controverses écrites, fait de la prison politique et proposé des projets d’avenir. Sa chance fut de vivre à une époque où les débats publics littéraires, politiques et sociaux étaient relativement ouverts et libres. En effet, autour de 1900, on trouve au Québec, outre le quotidien La Presse , fondée en 1884 et qui sert d’organe d’information, une presse d’opinion vivante et engagée, faite d’hebdomadaires où travaillent de petites équipes (parfois même un seul homme) et qui s’identifient nettement à des lignes idéologiques définies, sinon à des partis. La Minerve , journal d’Arthur Buies, vient de fermer en 1899. Il reste alors La Vérité de l’ultramontain Jules-Paul Tardivel, le journal libéral indépendant Les Débats fondé et dirigé par Louvigny de Montigny, suivi par Les vrais Débats , et par L’Avenir (du même) quand le parti libéral eut acheté le premier pour le soumettre et que Mgr Paul Bruchési l’eut condamné…. On trouve également Le Canada , propriété du parti libéral, Le Nationaliste , fondé en 1904 par Olivar Asselin pour critiquer la droite impérialiste et le haut-clergé, La Patrie , enfin Le Devoir que fonde Henri Bourassa en 1910 et qui existe encore aujourd’hui dans le format d’un quotidien.