CMR Quartet Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Music Cruises 2019 E.Pub

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart RHINE 2019 DUDOK QUARTET Aer compleng their studies with disncon at the Dutch String Quartet Academy in 20 3, the Quartet started to have success at internaonal compeons and to be recognized as one of the most promising young European string quartets of the year. In 20 4, they were awarded the Kersjes ,rize for their e-ceponal talent in the Dutch chamber music scene. .he Quartet was also laureate and winner of two special prizes during the 7th Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 3 1 2ordeau- and won st place at both the st Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 in 3adom 4,oland5 and the 27th 0harles 6ennen Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompe7 on 20 2. In 20 2, they received 2nd place at the 8th 9oseph 9oachim Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompeon in Weimar 4:ermany5. .he members of the quartet ;rst met in the Dutch street sym7 phony orchestra “3iccio=”. From 2009 unl 20 , they stu7 died with the Alban 2erg Quartet at the School of Music in 0ologne, then to study with Marc Danel at the Dutch String Quartet Academy. During the same period, the quartet was coached intensively by Eberhard Feltz, ,eter 0ropper 4Aindsay Quartet5, Auc7Marie Aguera 4Quatuor BsaCe5 and Stefan Metz. Many well7Dnown contemporary classical composers such as Kaija Saariaho, MarD7Anthony .urnage, 0alliope .sou7 paDi and Ma- Knigge also worDed with the quartet. In 20 4, the Quartet signed on for several recordings with 3esonus 0lassics, the worldEs ;rst solely digital classical music label. -

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2013-2014 THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY oF LINCOLN CENTER Thursday, April 10, 2014 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions and performances of contemporary music. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Presented in association with: The Chamber Music Society’s touring program is made possible in part by the Lila Acheson and DeWitt Wallace Endowment Fund. Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Thursday, April 10, 2014 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC THE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY oF LINCOLN CENTER • Gilles Vonsattel, piano Nicolas Dautricourt, violin Nicolas Altstaedt, cello Amphion String Quartet Katie Hyun, violin David Southorn, violin Wei-Yang Andy Lin, viola Mihai Marica, cello Tara Helen O'Connor, flute Romie de Guise-Langlois, clarinet Jörg Widmann, clarinet Ian David Rosenbaum, percussion 1 Program PIERRE JALBERT (B. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Kronos Quartet

K RONOS QUARTET SUNRISE o f the PLANETARY DREAM COLLECTOR Music o f TERRY RILEY TERRY RILEY (b. 1935) KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, VIOLIN 1. Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector 12:31 John Sherba, VIOLIN Hank Dutt, VIOLA 2. One Earth, One People, One Love 9:00 CELLO (1–2) from Sun Rings Sunny Yang, Joan Jeanrenaud, CELLO (3–4, 6–16) 3. Cry of a Lady 5:09 with Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares Jennifer Culp, CELLO (5) Dora Hristova, conductor 4. G Song 9:39 5. Lacrymosa – Remembering Kevin 8:28 Cadenza on the Night Plain 6. Introduction 2:19 7. Cadenza: Violin I 2:34 8. Where Was Wisdom When We Went West? 3:05 9. Cadenza: Viola 2:24 10. March of the Old Timers Reefer Division 2:19 11. Cadenza: Violin II 2:02 12. Tuning to Rolling Thunder 4:53 13. The Night Cry of Black Buffalo Woman 2:53 1 4. Cadenza: Cello 1:08 15. Gathering of the Spiral Clan 5:24 16. Captain Jack Has the Last Word 1:42 from left: Joan Jeanrenaud, John Sherba, Terry Riley, Hank Dutt, and David Harrington (1983, photo by James M. Brown) Sunrise of the Planetary possibilities of life. It helped the Dream Collector (1980) imagination open up to the possibilities It had been raining steadily that day surrounding us, to new possibilities in 1980 when the Kronos Quartet drove up curiosity he stopped by to hear the quartet Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector for interpretation.” —John Sherba to the Sierra Foothills to receive Sunrise practice. -

Schubert's Flights of Fantasie

Kristian Chong & Friends Schubert’s Flights of Fantasie LOCAL Monday, 2 May 2016 6pm, Salon HEROES Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Kristian Chong & Friends ARTISTS Sophie Rowell, violin Kristian Chong, piano PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Sonata for Piano and Violin in B-flat, K.454 I Largo - Allegro II Andante III Rondo: Allegretto ANDREW SCHULTZ Night Flight (2003) FRANZ SCHUBERT Fantasie for Piano and Violin in C, D.934 Andante molto–Allegretto–Andantino–Tempo I–Allegro vivace–Allegretto–Presto ABOUT THE MUSIC As was customary at the time, Mozart termed his early examples “sonatas for piano with violin ad libitum” but not the later Sonata K454, which he characterised as a “sonata for piano with violin accompaniment”. Yet this is a true chamber partnership, with K454 demanding a violinist of consummate skill. The opening commences with a stately Largo; it quickly retreats into a tender statement before launching into a swift Allegro with many conversational imitations and parallel lines. An Andante follows in which Mozart achieves a masterly blend of cantabile and beauty. A minor episode darkens the mood while maintaining enchanting lyricism. The concluding movement opens with a statement first spoken by the violin, with intervening episodes sandwiched between reprises of the theme giving opportunities to express Mozart’s penchant for unexpected and delectable melodic twists and turns. Night Flight was originally written as the fourth movement from a sextet called Mephisto in 1990. Ukranian violinist Dmitri Tkachenko commissioned this transcription and debuted it with Kristian Chong in London in 2003. The piece is a danse macabre for the modern age. -

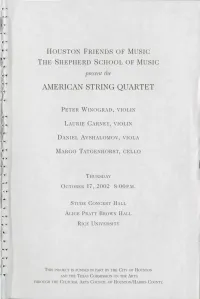

I.," American String Quartet

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the AMERICAN STRING QUARTET PETER WINOGRAD, VIOLIN LAURIE CARNEY, VIOLIN DANIEL AVSHALOMOV, VIOLA MARGO TATGENHORST, CELLO THURSDAY OCTOBER 17, 2002 8:00P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY I.," THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY TIIE CITY OF HOUSTON ~: AND THE TEXAS COMMISSION ON TIIE ARTS THROUGH TIIE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF IIOUSTON/lL-\RRJS COUNTY. AMERICAN STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) • Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 42 8 Allegro non troppo Andante con moto Menuetto: Allegro Allegro vivace DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Quartet No. 3 in F Major, Op. 73 (1946) Allegretto Moderato con moto Allegro non troppo Adagio Moderato - INTERMISSIO - MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) String Quartet in F Major Allegro moderato: Tres doux Assez vif: Tres rhythme Tres lent .,... Vif et agite WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 428 . t • Until the great quartets of Haydn and Mozart, eighteenth century · t r chamber music had been written primarily for the private use of ama - r teurs. As the century progressed, the dominance of complex, Baroque compositional methods had diminished and the style of writing had been simplified, making it easier for an amateur to master. Yet, at the same time in Vienna, the public performance of larger-scale, symphonic music came into vogue. And as this was written for professionals, the composer could explore greater complexity, even bringing back some of the intricate devices of baroque music such as fugues. Furthermore, in the last decades of the century, a full-time, professional quartet was maintained in Vienna by Count Razumovsky for performances at the great houses. -

Whlive0012 Booklet 14/8/06 12:12 Pm Page 2

WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 2 WHLive0012 Also Available Made & Printed in England NASH ENSEMBLE Beethoven Clarinet Trio in Bb Mendelssohn Octet SIR THOMAS ALLEN baritone WHLive0001 MALCOLM MARTINEAU piano Songs by Beethoven, Wolf, Butterworth Vaughan Williams and Bridge 0002 ARDITTI QUARTET WHLive Nancarrow String Quartet No. 3 Ligeti String Quartet No. 2 DAME FELICITY LOTT soprano Dutilleux String Quartet ‘Ainsi la nuit’ GRAHAM JOHNSON piano 0003 WHLive Fallen Women and Virtuous Wives Songs by Haydn, Strauss, Brahms and Wolf WHLive0004 ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC Concerti and Concerti Grossi by Handel, JS Bach and Vivaldi PETER SCHREIER tenor WHLive0005 ANDRÁS SCHIFF piano Schubert Songs WHLive0006 NASH ENSEMBLE Schumann Märchenerzählungen Moscheles Fantasy, Variations & Finale DAME MARGARET PRICE soprano Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor GEOFFREY PARSONS piano WHLive0007 Songs by Schubert, Mahler and R Strauss JOYCE DIDONATO mezzo-soprano WHLive0008 JULIUS DRAKE piano Songs by Fauré, Hahn and Head KOPELMAN QUARTET Arias by Rossini and Handel Schubert String Quartet in D minor 0009 WHLive ‘Death and the Maiden’ Tchaikovsky String Quartet in Eb minor WHLive0010 SOILE ISOKOSKI soprano MARITA VIITASALO piano Songs by Sibelius, Strauss and Berg WHLive0011 Available from all good record shops and from www.wigmore-hall.org.uk/live WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 3 Ysaÿe Quartet Debussy String Quartet in G minor Stravinsky Concertino Three Pieces for String Quartet Double Canon Fauré String Quartet in E minor WHLive0012 booklet 14/8/06 12:12 pm Page 4 Ysaÿe Quartet CLAUDE DEBUSSY String Quartet in G minor Op. 10 (1893) 01 Animé et très décidé 07.04 02 Assez vif et bien rythmé 03.50 03 Andantino, doucement expressif 08.17 04 Très modéré – Très mouvementé avec passion 07.24 IGOR STRAVINSKY 05 Concertino (1920) 07.00 Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914) 06 ‘Dance’ 00.49 07 ‘Eccentric’ 01.51 08 ‘Canticle’ 04.46 09 Double Canon (1959) 02.16 GABRIEL FAURÉ String Quartet in E minor Op. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i.