Kronos Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

CONTINUING EDUCATION Quality Education

FALL 2008 YorkCOLLEGE CONTINUING EDUCATION Lifetime Opportunities. Quality Education. Computer Courses page 5 2 page ses Cour ness Busi Certificate Programs page 7 e 25 s pag ourse Kids C Enrichment Courses page 35 Welcome! Table of Contents The Continuing Education Department at York College would like to welcome you to another semester of exciting programs and activities that will improve and enrich your life. Please take a Welcome to the Fall 2008 Semester. moment to look through our brochure and choose from an array of courses. We are dedicated to serving our community. We pro- With over 100 courses to choose from, vide quality education that can lead to lifetime opportunities. there’s something for everyone. Business and Careers . .2-3 Find skills you need to grow on your job or explore starting you own business. Computers and Professional Development . .4-6 Word, Excel, Quickbooks, Child Care, Notary Public. CertifiedCareer Training Nursing Children’s Academy Fitness and Fun pageAssistant 2-11 page 25-32 page 36-43 Certificate Programs . .7-19 page 14 Obtain a state, association or professional certificate to give you that competitive edge in the job market. Allied Health Certificate Programs . .22-24 The verdict is in. Health is where Learn the skills of the industry with the most demand for jobs on A career as a Paralegal the market today. is a winning proposition! the wealth is… Children’s Academy (Kids, Tweens & Teens) . .25-32 Fun and Fitness, Music, Arts and Crafts, Academics. We have it all! Personal Enrichment . .33-35 Learn a new language, brush up your academic skills or prepare for your High School Equivalency. -

Kronos Quartet

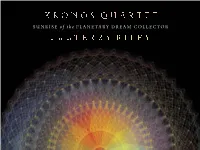

K RONOS QUARTET SUNRISE o f the PLANETARY DREAM COLLECTOR Music o f TERRY RILEY TERRY RILEY (b. 1935) KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, VIOLIN 1. Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector 12:31 John Sherba, VIOLIN Hank Dutt, VIOLA 2. One Earth, One People, One Love 9:00 CELLO (1–2) from Sun Rings Sunny Yang, Joan Jeanrenaud, CELLO (3–4, 6–16) 3. Cry of a Lady 5:09 with Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares Jennifer Culp, CELLO (5) Dora Hristova, conductor 4. G Song 9:39 5. Lacrymosa – Remembering Kevin 8:28 Cadenza on the Night Plain 6. Introduction 2:19 7. Cadenza: Violin I 2:34 8. Where Was Wisdom When We Went West? 3:05 9. Cadenza: Viola 2:24 10. March of the Old Timers Reefer Division 2:19 11. Cadenza: Violin II 2:02 12. Tuning to Rolling Thunder 4:53 13. The Night Cry of Black Buffalo Woman 2:53 1 4. Cadenza: Cello 1:08 15. Gathering of the Spiral Clan 5:24 16. Captain Jack Has the Last Word 1:42 from left: Joan Jeanrenaud, John Sherba, Terry Riley, Hank Dutt, and David Harrington (1983, photo by James M. Brown) Sunrise of the Planetary possibilities of life. It helped the Dream Collector (1980) imagination open up to the possibilities It had been raining steadily that day surrounding us, to new possibilities in 1980 when the Kronos Quartet drove up curiosity he stopped by to hear the quartet Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector for interpretation.” —John Sherba to the Sierra Foothills to receive Sunrise practice. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 23, 2016 CONTACT: Ren Mitchell 832-314-9994 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 23, 2016 CONTACT: Ren Mitchell 832-314-9994 [email protected] Karen Stokes Dance presents DEEP: Seaspace at Zilkha Hall, Hobby Center for Performing Arts HOUSTON, TX: Karen Stokes Dance presents “DEEP: Seaspace” October 20-22, 2016 at 8:00pm at the Hobby Center for Performing Arts, Zilkha Hall. “DEEP: Seaspace” is the culminating performance of a multi-year initiative inspired by the history and landmarks of the City of Houston. With an original score by composer Bill Ryan played live by nationally recognized musicians, the evening length live performance will explore Houston for two if its defining industries: sea and space. “DEEP: Seaspace” fuses history, landscape, dance, and music through the lens of two iconic Houston enterprises: The Houston Ship Channel and NASA. While Sea speaks to the pioneering spirit of the founding of Houston along the banks of Buffalo Bayou and the formation of the Houston Ship Channel, Space is inspired by Houston’s stronghold in space exploration and human achievement. Celebrating Houston's unique heritage and Texas’ pioneering spirit, “DEEP: Seaspace” investigates the core of human progress, the fundamental spirit of Houston, and the desire to understand the unknown to forge a better tomorrow. In “DEEP: Seaspace,” Stokes explores “launching” and “landing” through a unique blend of quirky and innovative choreographic styles that has become the trademark of her 20 years of work in contemporary dance. Stokes has received regional and national acclaim for her choreography including being name “Best Choreographer in Houston” in both 2014 and 2015 by the Houston Press. Nancy Wozny, of Texas Arts & Culture, wrote: “In Houston, it’s Karen Stokes who comes to mind as an artist tightly tied to Texas. -

New Music at Macalester Presents the ETHEL String Quartet Performing

New Music at Macalester presents the ETHEL string quartet performing... http://www.macalester.edu/news/2013/08/new-music-at-macalester-prese... New Music at Macalester presents the ETHEL string quartet performing “GRACE” St. Paul, Minn. – Since its founding in 1998, the string quartet ETHEL has been a musical pioneer. They’ll perform at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, September 10, 2013, in Mairs Concert Hall, in the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center & Gallery, 1600 Grand Ave, St. Paul, Minn. They are part of Macalester’s New Music Series , sponsored by the Rivendell Foundation. Their Macalester concert, titled "GRACE," is a program that explores the idea of redemption through music. The performance will include a suite from the score to the film "The Mission" by Ennio Morricone, as well as music from other cultures. The New York-based string quartet uses amplification and improvisation in its concerts performing original music and works by contemporary composers. The New Yorker has called ETHEL the "avatar of post-classical music -- the virtuoso alternative string quartet...vital and brilliant." Download (//d2ihvqrbsd9p9p.cloudfront.net /contentAsset/raw-data ETHEL is comprised of Ralph Farris (viola), Dorothy Lawson /f6ac8962-1917-4184-b90d-26faffacb7e6 (cello), Kip Jones (violin) and Tema Watstein (violin). /image1 ) Thanks to generous funding from the Rivendell Foundation, the Macalester College Music Department presents two to three concerts per season focusing on New Music and Jazz. Past New Music Series guests have included guitarist/composer Bill Frisell, cellist Matt Haimovitz, So Percussion, jazz pianist/composer/arranger Uri Caine, singer Lucy Shelton, Enso String Quartet, pianist/composer Frederic Rzewski, Pulitzer-Prize winning composer Yehudi Wyner, chamber group eighth blackbird, and jazz composer/bandleader Maria Schneider and Theo Bleckmann, jazz singer and new music composer. -

The Jewish Museum and Bang on a Can Present ETHEL Performing the String Quartets of Julia Wolfe

The Jewish Museum and Bang on a Can Present ETHEL Performing the String Quartets of Julia Wolfe Photos by Matthew Murphy (ETHEL) and Peter Serling (Julia Wolfe) Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 7:30pm Scheuer Auditorium at the Jewish Museum 1109 5th Ave at 92nd St | New York, NY Tickets: $20 General; $16 Students and Seniors; $12 Jewish Museum Members Available at www.thejewishmuseum.org. Includes museum admission. New York, NY – Bang on a Can and the Jewish Museum’s 2018-2019 concert season, pairing innovative music with the Museum’s exhibitions and showcasing leading female performers and composers, continues on Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 7:30pm. The acclaimed string quartet ETHEL performs the complete string quartets of Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Julia Wolfe: Dig Deep, Early that Summer, Four Marys, and Blue Dress. This is the first performance of all of Wolfe's string quartets at one time, on one stage. Julia Wolfe's string quartets, as described by The New Yorker, "combine the violent forward drive of rock music with an aura of minimalist serenity [using] the four instruments as a big guitar, whipping psychedelic states of mind into frenzied and ecstatic climaxes." This performance is presented in conjunction with the exhibition of fellow New York City cultural icon Martha Rosler: Irrespective. Established in New York City in 1998, ETHEL quickly earned a reputation as one of America’s most adventurous string quartets. Twenty years later, the band continues to set the standard for contemporary concert music. ETHEL is Ralph Farris (viola), Kip Jones (violin), Dorothy Lawson (cello), and Corin Lee (violin). -

Adam Schoenberg

SCHEDULE OF PERFORMANCES AND EVENTS - check denison.edu/series/tutti Monday, March 4, 6:30 pm, Knapp Performance Space Artist Talk with Vail Visiting Artist Tara Booth, ‘Inward & Onward: The Contemporary Ceramics of Tara Booth,’ Tuesday March 5, 10:00 am Swasey Chapel Workshop with Third Coast Percussion, ‘Think Outside the Drum” 8:00 pm, Denison Museum The Weather Project - Artist Talk and Concert with Nathalie Miebach and Student Composers Concert with ETHEL and Students, Wednesday, March 6, 1:30 pm, Swasey Chapel Composers Workshop with Third Coast Percussion on Composition, Swasey Chapel 6:30 pm, Burke Recital Hall Composition and Improvisation: Philosophers and Musicians in Dialogue with John Carvalho, Ted Gracyk, Mark Lomax II and ETHEL Thursday, March 7, 11:30 am, Burke Rehearsal Hall Composition Seminar with Adam Schoenberg, 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert One with Guest Artists and the Columbus Symphony Quartet 7:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Two with Denison Wind Ensemble and Symphony Orchestra, with guest artists ETHEL Friday, March 8, 10:00 am, Burke Recital Hall Concert Three with Faculty, Students and Guest Artists 11:30 am, Burke Rehearsal Room Conversation with: Third Coast Percussion, ETHEL, and Adam Schoenberg 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Four with Chamber Singers, Jazz Ensemble, Faculty and Guest Artists 7:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Five ‘Words and Music with ETHEL and Michael Lockwood Crouch, actor, and Denison Creative Writing Students, Saturday, March 9, 10:00 am, Knapp Performance Space Concert Six with Faculty and Guest Artists, 11:00 am, Composers Forum - Knapp (various locations) - Composers 3:00 pm, Burke Recital Hall Concert Seven ‘New American Music Project 3. -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

Volume I (Final) Proofread

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5h4626dd Author Lee, Hyunjong Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctoral of Philosophy in Music by Hyunjong Lee 2014 © copyright by Hyunjong Lee 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly by Hyunjong Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes in this dissertation: the first is a monograph, and the second a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I These days, labels such as classical, rock and pop mean less and less since young musicians frequently blur boundaries between genres. These young musicians have built an alternative musical universe. I construct five different categories to explore this universe. They are 1) circuits of alternate concert venues, 2) cross-genre collaborations, 3) alternative modes of musical groups, 4) new compositional trends in classical chamber music, and 5) new ensembles and record labels. ii In this dissertation, I aim to explore these five categories, connecting them to recent cultural trends in New York. -

Catalogo Per Autori Ed Esecutori

Abel, Carl Friedrich Quartetti, archi, Op. 8, No. 5, la maggiore The Salomon Quartet The Schein String Quartet Addy, Obo Wawshishijay Kronos Quartet Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund Zwei Stucke fur Strechquartett op. 2 Buchberger Quartett Albert, Eugene : de Quartetti, archi, Op. 7, la minore Sarastro Quartett Quartetti, archi, Op. 11, mi bemolle maggiore Sarastro Quartett Alvarez, Javier Metro Chabacano Cuarteto Latinoamericano 1 Alwyn, William Quartetti, archi, n. 3 Quartet of London Rhapsody for String Quartet Arditti string quartet Andersson, Per Polska fran Hammarsvall, Delsbo The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom Quartet The Skane Quartet Andriessen, Hendrik Il pensiero Raphael Quartet Aperghis, Georges Triangle Carre Trio Le Cercle Apostel, Hans Erich Quartetti, archi, Op. 7 LaSalle Quartet Arenskij, Anton Stepanovic Quartetti, archi, op. 35 Paul Rosenthal, Vl Matthias Maurer, Vla Godfried Hoogeveen, Vlc Nathaniel Rosen, Vlc Arriaga y Balzola, Juan Crisostomo Jacobo Antonio : de Quartetti, archi, No. 1, re minore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Quartetti, archi, No. 2, la maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet 2 Quartetti, archi, Nr. 3, mi bemolle maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Atterberg, Kurt Quartetti, archi, Op. 11 The Garaguly Quartet Aulin, Tor Vaggvisa The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom -

Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2011 Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Mackey, Steven, "Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 155. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/155 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Chamber Music of Steven Mackey The 2010-2011 Husa Visiting Professor of Composition Hockett Family Recital Hall Sunday, April 17, 2011 4:00 p.m. Indigenous Instruments Jacqueline Christen*, flute/piccolo Adam Butalewicz*, clarinet Kate Goldstein*, violin Nathan Gulla*, piano Richard Faria**, conductor Measures of Turbulence Eric Pearson, Matt Gillen, Nick Throop, Nick Malishak, Russ Knifin, guitar Dave Moore, Scott Card, electric guitar Sam Verneuille, electric bass Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Intermission Gaggle and Flock Gaggle Flock Nicholas DiEugenio**, Susan Waterbury**, Isaac Shiman, Sadie Kenny, violin Zachary Slack, Max Aleman, viola Elizabeth Simkin**, Peter Volpert, cello Jeffery Meyer**, conductor * Ithaca College Alumni ** Ithaca College Faculty Biography Steven Mackey Steven Mackey was born in 1956 to American parents stationed in Frankfurt, Germany. His first musical passion was playing the electric guitar, in rock bands based in northern California. He later discovered concert music and has composed for orchestras, chamber ensembles, dance, and opera. He regularly performs his own works, including two electric guitar concertos and numerous solo and chamber works, and is also active as an improvising musician and performs with his band Big Farm.