Celebrating Vedantic Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sage of Vasishtha Guha - the Last Phase

THE SAGE OF VASISHTHA GUHA - THE LAST PHASE by SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA THE SAGE OF VASISHTHA GUHA - THE LAST PHASE by SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA Published By SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA VILLAGE : KURTHA, GHAZIPUR - - 233 001. (C) SHRI PURUSHOTTAMANANDA TRUST First Edition 1975 Copies can be had from : SHRI M. P. SRIVASTAVA, 153 RAJENDRANAGAR, LUCKNOW - 226 004. Printed at SEVAIi PRESS, Bombay-400 019 (India) DEDICATION What is Thine own, 0 Master! F offer unto Thee alone c^'-q R;q q^ II CONTENTS Chapter. Page PREFACE 1 THE COMPASSIONATE GURU 1 II A SANNYASA CEREMONY ... ii 111 PUBLICATION OF BIOGRAPHY ... ... 6 IV ARDHA-KUMBHA AT PRAYAG ... ... 8 V A NEW KUTIR ... 12 VI ON A TOUR TO THE SOUTH 13 VII OMKARASHRAMA 10 VIII TOWARDS KANYAKUMARI ... ... 18 IX THE RETURN JOURNEY ... ... 23 X THE CRUISE ON THE PAMPA ... ... 24 XI VISIT TO THE HOUSE OF BIRTH ... ... 27 XII GOOD-BYE TO THE SOUTH ... ... 28 XLII RISHIKESH - VASISHTHA GUHA ... ... 29 XIV TWO SANNYASA CEREMONIES ... 30 XV AT THE DEATH-BED OF A DISCIPL E ... 32 XVI THE LAST TOUR ... 35 XVII MAHASAMADHI & AFTER ... 30 XVIII VASISHTHA GUHA ASHRAMA TODAY ... 48 APPENDIX ... 50 Tre lace T HE Sage of Vasishtha Guha, the Most Revered Skvami Puru- shottamanandaji Maharaj, attained Mahasamadhi in the year 1961. This little volume covers the last two years of his sojourn on earth and is being presented to the readers as a com- plement to "The Life of Swami Purushottamananda," published in 1959. More than twelve years have elapsed since Swamiji's Mahasamadhi and it is only now that details could be collected and put in the form of a book. -

Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda Mrs Alice M Hansbrough (Continued from the Previous Issue)

Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda Mrs Alice M Hansbrough (Continued from the previous issue) o you remember any incidents in con- ‘No.’ nection with any of these meetings?’ ‘Well, it was clear aft erward that the group who the swami asked. had asked for this subject had done so in an attempt ‘D‘I remember that on one occasion when Swamiji to trap Swamiji into saying something that would was going to speak at the Green Hotel, Professor discredit him. We learned later that they belonged Baumgardt was talking with some other gentlemen to some group who had missionaries in India. Th e on the platform before the lecture began. One of questions they asked were along the line always them asked him, regarding Swamiji, “He is a Chris- taken by those trying to discredit India: the claim tianized Hindu, I suppose?” And Professor Baum- of abuse of Indian women, child marriages, early gardt replied, “No, he is an unconverted Hindu. motherhood, and so on. You will hear about Hinduism from a real Hindu.” ‘Swamiji answered several of the questions direct- ‘On another occasion, Swamiji was speaking in ly; then when he saw the direction the questioner some church. I do not remember now why, but he was taking, he said that the relationship between did not have a previously announced subject on the husband and wife in India, where the basis of that occasion. So when he came on the platform marriage was not physical enjoyment, was so entirely he asked the audience what they would like to have diff erent from that of a married couple in the West him speak on. -

The Contemplative Life – Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj

The Contemplative Life – Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj. Most Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj was the 15th President of the world -wide Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission. In this article Most Revered Maharaj provides guidelines on how to lead a contemplative life citing many personal reminiscences of senior monks of the Ramakrishna tradition who lead inspiring spiritual lives. Source : Prabuddha Bharata – Jan 2007 SADHAN-BHAJAN or spiritual practice – japa, prayer and meditation – should play a very vital role in the lives of all. This is a sure way to peace despite all the hindrances that one has to face in daily life. The usual complaint is that it is very difficult to lead an inward life of sadhana or contemplation amidst the rush and bustle of everyday life. But with earnestness and unshakable determination one is sure to succeed. Sri Ramakrishna has said that a devotee should hold on to the feet of the Lord with the right hand and clear the obstacles of everyday life with the other. There are two primary obstacles to contemplative life. The first one is posed by personal internal weaknesses. One must have unswerving determination to surmount these. The second one consists of external problems. These we have to keep out, knowing them to be harmful impediments to our goal. For success in contemplative life, one needs earnestness and regularity. Study of the scriptures, holy company, and quiet living help develop our inner lives. I have clearly seen that all the great swamis of our Order have led a life of contemplation even in the midst of great distractions. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

Adi Sankaracharya's VIVEKACHUDAMANI

Adi Sankaracharya's VIVEKACHUDAMANI Translated by Swami Madhavananda Published by Advaita Ashram, Kolkatta 1. I bow to Govinda, whose nature is Bliss Supreme, who is the Sadguru, who can be known only from the import of all Vedanta, and who is beyond the reach of speech and mind. 2. For all beings a human birth is difficult to obtain, more so is a male body; rarer than that is Brahmanahood; rarer still is the attachment to the path of Vedic religion; higher than this is erudition in the scriptures; discrimination between the Self and not-Self, Realisation, and continuing in a state of identity with Brahman – these come next in order. (This kind of) Mukti (Liberation) is not to be attained except through the well- earned merits of a hundred crore of births. 3. These are three things which are rare indeed and are due to the grace of God – namely, a human birth, the longing for Liberation, and the protecting care of a perfected sage. 4. The man who, having by some means obtained a human birth, with a male body and mastery of the Vedas to boot, is foolish enough not to exert himself for self-liberation, verily commits suicide, for he kills himself by clinging to things unreal. 5. What greater fool is there than the man who having obtained a rare human body, and a masculine body too, neglects to achieve the real end of this life ? 6. Let people quote the Scriptures and sacrifice to the gods, let them perform rituals and worship the deities, but there is no Liberation without the realisation of one’s identity with the Atman, no, not even in the lifetime of a hundred Brahmas put together. -

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: from Swami Vivekananda to the Present

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis in Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017) Appendix II: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis (1893-2017) Appendix III: Presently Existing Ramakrishna-Vedanta Centers in North America (2017) Appendix IV: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis from India in North America (1893-2017) Bibliography Alphabetized by Abbreviation Endnotes Appendix 12/13/2020 Page 1 Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna Vedanta Swamis Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017)1 Southern California Vivekananda (1899-1900) to India Turiyananda (1900-02) to India Abhedananda (1901, 1905, 1913?, 1914-18, 1920-21) to India—possibly more years Trigunatitananda (1903-04, 1911) Sachchidananda II (1905-12) to India Prakashananda (1906, 1924)—possibly more years Bodhananda (1912, 1925-27) Paramananda (1915-23) Prabhavananda (1924, 1928) _______________ La Crescenta Paramananda (1923-40) Akhilananda (1926) to Boston _______________ Prabhavananda (Dec. 1929-July 1976) Ghanananda (Jan-Sept. 1948, Temporary) to London, England (Names of Assistant Swamis are indented) Aseshananda (Oct. 1949-Feb. 1955) to Portland, OR Vandanananda (July 1955-Sept. 1969) to India Ritajananda (Aug. 1959-Nov. 1961) to Gretz, France Sastrananda (Summer 1964-May 1967) to India Budhananda (Fall 1965-Summer 1966, Temporary) to India Asaktananda (Feb. 1967-July 1975) to India Chetanananda (June 1971-Feb. 1978) to St. Louis, MO Swahananda (Dec. 1976-2012) Aparananda (Dec. 1978-85) to Berkeley, CA Sarvadevananda (May 1993-2012) Sarvadevananda (Oct. 2012-) Sarvapriyananda (Dec. 2015-Dec. 2016) to New York (Westside) Resident Ministers of Affiliated Centers: Ridgely, NY Vivekananda (1895-96, 1899) Abhedananda (1899) Turiyananda (1899) _______________ (Horizontal line means a new organization) Atmarupananda (1997-2004) Pr. -

Spiritual Practice

SPIRITUAL PRACTICE ITS CONDITIONS AND PRELIMINARIES by SWAMI ASHOKANANDA Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..............................................................3 IN THE OUTER COURT.......................................................4 SANDHYÂ-VANDANÂ AND KIRTANÂ........................................11 PRÂNÂYÂMA.................................................................16 INTELLECTUALISM VERSUS SPIRITUALITY...............................21 ON THE THRESHOLD.......................................................27 WHEN SHALL WE RENOUNCE?.............................................32 IS RENUNCIATION NECESSARY?............................................39 EXTERNAL RENUNCIATION.................................................44 IS HUMAN LOVE A HELP?...................................................50 THE CASE OF THE UNMARRIED...........................................55 THE CASE OF THE MARRIED...............................................61 KARMA-YOGÂ...............................................................66 BRAHMACHARYA............................................................71 THE QUESTION OF FOOD..................................................77 THE NECESSITY OF THE GURU............................................83 SIGNS OF A TRUE GURU....................................................88 CONCLUSION................................................................93 Advaita Ashrama Calcutta Swami Ashokananda (1893-1969) a much-venerated monk of the Ramakrishna Order was ordained into Sannyâsa by Swami Shivananda, -

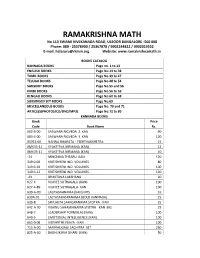

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi

american vedantist Volume 15 No. 3 • Fall 2009 Sri Sarada Devi’s house at Jayrambati (West Bengal, India), where she lived for most of her life/Alan Perry photo (2002) Used by permission Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi Vivekananda on The First Manifestation — Page 3 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE A NOTE TO OUR READERS American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is dedicated to developing VedantaVedanta in the West,West, es- American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is a not-for-profinot-for-profi t, quarterly journal staffedstaffed solely by pecially in the United States, and to making The Perennial Philosophy available volunteers. Vedanta West Communications Inc. publishes AV four times a year. to people who are not able to reach a Vedanta center. We are also dedicated We welcome from our readers personal essays, articles and poems related to to developing a closer community among Vedantists. spiritual life and the furtherance of Vedanta. All articles submitted must be typed We are committed to: and double-spaced. If quotations are given, be prepared to furnish sources. It • Stimulating inner growth through shared devotion to the ideals and practice is helpful to us if you accompany your typed material by a CD or fl oppy disk, of Vedanta with your text fi le in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Manuscripts also may • Encouraging critical discussion among Vedantists about how inner and outer be submitted by email to [email protected], as attached fi les (preferred) growth can be achieved or as part of the e mail message. • Exploring new ways in which Vedanta can be expressed in a Western Single copy price: $5, which includes U.S.