Memory Work on R ¯Ekohu (Chatham Islands) Kingsley Baird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

LIST of MEMBERS on 1St MAY 1962

LIST OF MEMBERS ON 1st MAY 1962 HONORARY MEMBERS Champion, Sir Harry, CLE., D.Sc, M.A., Imperial Forestry Institute, Oxford University, Oxford, England Chapman, H. H., M.F., D.Sc, School of Forestry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticutt, U.S.A, Cunningham, G. H., D.Sc, Ph.D., F.R.S.(N.S.), Plant Research Bureau, D.S.I.R., Auckland Deans, James, "Homebush", Darfield Entrican, A. R., C.B.E., A.M.I.C.E., 117 Main Road, Wellington, W.3 Foster, F. W., B.A. B.Sc.F., Onehuka Road, Lower Hutt Foweraker, C. E., M.A., F.L.S., 102B Hackthorne Road, Christchurch Jacobs, M. R., M.Sc, Dr.Ing., Ph.D., Dip.For., Australian Forestry School, Canberra, A.C.T. Larsen, C Syrach, M.Sc, Dr.Ag., Arboretum, Horsholm, Denmark Legat, C. E., C.B.E., B.Sc, Beechdene, Lower Bourne, Farnham, Surrey, England Miller, D., Ph.D., M.Sc, F.R.S., Cawthron Institute, Nelson Rodger, G. J., B.Sc, 38 Lymington Street, Tusmore, South Australia Spurr, S. TL, B.S., M.F., Ph.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Taylor, N. IL, O.B.E., Soil Research Bureau, D.S.I.R., Wellington MEMBERS Allsop, F., N.Z.F.S., P.B., Wellington Armitage, M. F., N.Z.F.S., P.O. Box 513, Christchurch Barker, C. S., N.Z.F.S., P.B., Wellington Bay, Bendt, N.Z. Forest Products Ltd., Tokoroa Beveridge, A. E., Forest Reasearch Institute, P.B., Whakarewarewa, Rotorua Brown, C. H., c/o F.A.O., de los N.U., Casilla 10095, Santiago de Chile Buchanan, J. -

In Liquidation)

Liquidators’ First Report on the State of Affairs of Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 8 March 2019 Contents Introduction 2 Statement of Affairs 4 Creditors 5 Proposals for Conducting the Liquidation 6 Creditors' Meeting 7 Estimated Date of Completion of Liquidation 8 Appendix A – Statement of Affairs 9 Appendix B – Schedule of known creditors 10 Appendix C – Creditor Claim Form 38 Appendix D - DIRRI 40 Liquidators First Report Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 1 Introduction David Ian Ruscoe and Malcolm Russell Moore, of Grant Thornton New Zealand Limited (Grant Thornton), were appointed joint and several Interim Liquidators of the Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) (the “Trust” or “Taratahi”) by the High Count in Wellington on 19 December 2018. Mr Ruscoe and Mr Moore were then appointed Liquidators of the Trust on 5th February 2019 at 10.50am by Order of the High Court. The Liquidators and Grant Thornton are independent of the Trust. The Liquidators’ Declaration of Independence, Relevant Relationships and Indemnities (“DIRRI”) is attached to this report as Appendix D. The Liquidators set out below our first report on the state of the affairs of the Companies as required by section 255(2)(c)(ii)(A) of the Companies Act 1993 (the “Act”). Restrictions This report has been prepared by us in accordance with and for the purpose of section 255 of the Act. It is prepared for the sole purpose of reporting on the state of affairs with respect to the Trust in liquidation and the conduct of the liquidation. -

New Zealand 2021-2022 Guided Holidays

NEW ZEALAND 2021-2022 GUIDED HOLIDAYS 3-17 day Fully Curated Experiences 8-21 day Flexible Guided Holidays New Zealand Vista 14 DAYS AUCKLAND CHRISTCHURCH LAAC 14 INCLUDED EXPERIENCES HIGHLIGHTS Choose from a wide variety of sightseeing options – there is something to suit all tastes FLEXIBLE and travel styles. HOLIDAYS Explore famous Milford Sound and the spectacular Fiordland National Park, a UNESCO ICONIC World Heritage site. SITES Feel free to explore, with two nights in Rotorua and Queenstown to wine and TIME dine where you choose. FOR YOU Lunch is supplied through Eat My Lunch, an organisation that has given over 1.5 million SUSTAINABLE lunches to Kiwi kids. TRAVEL START END 1 Number of night stays Sightseeing stops AUCKLAND 1 Rotorua 2 Waitomo Caves Lake Taupo Huka Falls Mt. Ruapehu Franz Josef Glacier Picton 1 1 Wellington Mt. Cook Arthur’s Kaikoura Hokitika Pass TranzAlpine Train 1 Haast 1 1 CHRISTCHURCH Omarama Milford 1 Queenstown Sound 2 Oamaru 1 Te Anau 1 Dunedin TSS Earnslaw firstlighttravel.com WHY YOU'LL LOVE 8 Omarama – Dunedin Travel along the Waitaki River, which marks the THIS TRIP: boundary between the regions of Canterbury and Otago, and with its large catchment, it is an y It spans both of New Zealand’s ideal source of hydro-electric power. Continue incredible islands through the historic town of Oamaru en route to Dunedin, New Zealand’s southernmost y Waitomo’s Glowworms are an city, where your afternoon is at leisure. incredible natural phenomenon Consider an optional experience. Perhaps tour imposing Larnach Castle, take a wildlife y The scenic journey onboard the cruise out to the Otago Peninsula to spot TSS Earnslaw is unforgettable penguins and the Royal Albatross or experience Auckland an interactive tour of famous Speight’s y See cascading Milford Sound, Huka Brewery. -

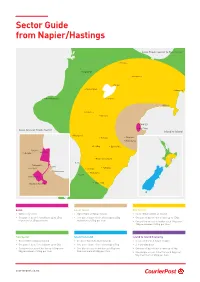

Sector Guide from Napier/Hastings

Sector Guide from Napier/Hastings Local Towns Sector to Two Sector • Rotorua Mangakino • Murupara • • Taupo • Taumarunui Gisborne • • New Plymouth • Turangi • Wairoa Ohakune • • Waiouru • NAPIER • HASTINGS Local & Local Towns Sector Island to Island • Whanganui • Taihape • Waipawa • Waipukurau • Feilding • Dannevirke Poraiti • Puketapu • NAPIER • • Palmerston North Foxton • Pakowhai • • Clive • Pahiatua • Fernhill • Shannon • Haumoana • Eketahuna • Levin HASTINGS • Havelock North • • Masterton Local Local Towns One Sector • Within city limits • Up to 75km within an Island • Up to 150km within an Island • One parcel base ticket allows up to 25kg • One parcel base ticket allows up to 25kg • One parcel base ticket allows up to 15kg maximum of 25kg per item maximum of 25kg per item • One yellow excess ticket for each 10kg over 15kg maximum of 25kg per item Two Sector Island to Island Island to Island Economy • Over 150km within an Island • Between North & South Islands • Between North & South Islands • One parcel base ticket allows up to 5kg • One parcel base ticket allows up to 5kg • 2-3 working days • One green excess ticket for each 5kg over • One blue excess ticket for each 5kg over • One parcel base ticket allows up to 5kg 5kg maximum of 25kg per item 5kg maximum of 25kg per item • One purple excess ticket for each 5kg over 5kg maximum of 25kg per item courierpost.co.nz CourierPost branch locations CourierPost Locations CourierPost Depot Address Auckland — City Auckland City CourierPost Depot 11 McDonald Street, Morningside, Auckland -

Patterns of Prehistoric Human Mobility in Polynesia Indicated by Mtdna from the Pacific Rat (Rattus Exulans͞population Mobility)

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 15145–15150, December 1998 Anthropology Patterns of prehistoric human mobility in Polynesia indicated by mtDNA from the Pacific rat (Rattus exulansypopulation mobility) E. MATISOO-SMITH*†,R.M.ROBERTS‡,G.J.IRWIN*, J. S. ALLEN*, D. PENNY§, AND D. M. LAMBERT¶ *Department of Anthropology and ‡School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, P. B. 92019 Auckland, New Zealand; and §Molecular Genetics Unit and ¶Department of Ecology, Massey University, P. B. 11222 Palmerston North, New Zealand Communicated by R. C. Green, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, October 14, 1998 (received for review July 20, 1998) ABSTRACT Human settlement of Polynesia was a major Recent genetic research focusing on Polynesian populations event in world prehistory. Despite the vastness of the distances has contributed significantly to our understanding of the covered, research suggests that prehistoric Polynesian popu- ultimate origins of this last major human migration. Studies of lations maintained spheres of continuing interaction for at globin gene variation (2) and mtDNA lineages of modern least some period of time in some regions. A low level of genetic Polynesians (3, 4) and studies of ancient DNA from Lapita- variation in ancestral Polynesian populations, genetic admix- associated skeletons (5) may indicate that some degree of ture (both prehistoric and post-European contact), and severe admixture with populations in Near Oceania occurred as more population crashes resulting from introduction of European remote biological ancestors left Southeast Asia and passed diseases make it difficult to trace prehistoric human mobility through Near Oceania. An alternative hypothesis is that the in the region by using only human genetic and morphological biological ancestors of these groups were one of a number of markers. -

Border Report – Port of Tauranga and Rotorua Airport August 2013

Border Report – Port of Tauranga and Rotorua Airport August 2013 Purpose A preliminary report to understand the level of risk the Port of Tauranga (POT) and Rotorua Airport present to the Bay of Plenty kiwifruit industry with the intent of determining if the current level of protection is adequate. Background Biosecurity in New Zealand consists of a multi –layer system that begins offshore with pre-border activities, incorporates the border and continues post-border into New Zealand where it becomes a joint effort between central government, regional councils, industry, community groups, and all New Zealanders, (a paper describing this system in more detail can be found on the KVH website www.kvh.org.nz/kiwifruit_biosecurity_risks). This paper will review a single layer, border interventions at ports of entry. Any port of entry has the potential to bring unwanted pests and diseases into New Zealand that could be detrimental to the kiwifruit industry, however, given the high concentration of the kiwifruit industry in the Bay of Plenty, this report has focused on the ports of entry in the immediate proximity to this region, which are the Port of Tauranga and the Rotorua Airport. The Port of Tauranga is New Zealand’s second largest port by container volume, and a major stop on the cruise ship circuit. Rotorua Airport is an International Airport receiving two trans-Tasman flights a week. Imports into POT, cruise ships, and passenger traffic through Rotorua Airport are all potential pathways for risk items to enter New Zealand and each will be reviewed to provide an overview of operations, potential risks that each present and how these risks are being mitigated. -

Advanced Geothermal Geology

Advanced Geothermal Geology The objective of this course is to provide an advanced overview of geothermal geology and 10-14 FEB 2020 state-of-the-art methodology and simulation tools. Location: GNS Wairakei Research Centre & University of Auckland TOPICS COVERED This course complements JOGMEC’s introductory course and is useful for: • Geoscientists who have completed the JOGMEC course and want to advance their knowledge • Geoscientists working for oil/exploration companies interested in geothermal geology practices • Geothermal geoscientists interested in state-of-the-art / current practice methodology • Senior students and/or researchers in geothermal or complementary fi elds www.gns.cri.nz/geothermal-workshop Cost*: $6,560+GST/per person REGISTER ■ Limited number of spaces available (max 15 attendees) * Includes internal NZ travel, ■ Minimum number of attendees required (12) accommodation and food NOW ■ Registrations close 20 December 2019* * Excludes international travel ■ Course commences in Rotorua * GNS Science reserves the right to cancel the course if minimum numbers are not reached by 20 December 2019. A full refund will be arranged for all registration fees received. CONTACT Angus Howden [email protected] Advanced Geothermal Geology WORKSHOP PROGRAMME Day 1 Introduction to New Zealand Geothermal Development Meet with GNS geothermal specialists and local iwi (Māori) in Rotorua, to view the Rotorua 10 Feb 2020 Caldera and thermal manifestations (including Pohutu Geyser) at Te Puia thermal area, learn Rotorua – Taupō about the cultural importance of geothermal activity to New Zealand’s indigenous Māori and New Zealand’s approach to community engagement. Travel with GNS staff to Taupō, with stops at Ohaaki and Wairakei, where Contact Energy staff and GNS will describe the geology and structure of the Taupō Volcanic Zone, and history of geothermal development. -

Rekohu Report (2016 Newc).Vp

Rekohu REKOHU AReporton MorioriandNgatiMutungaClaims in the Chatham Islands Wa i 6 4 WaitangiTribunalReport2001 The cover design by Cliff Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfoldsinapatternnotyetcompletelyknown AWaitangiTribunalreport isbn 978-1-86956-260-1 © Waitangi Tribunal 2001 Reprinted with corrections 2016 www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by Printlink, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Set in Adobe Minion and Cronos multiple master typefaces e nga mana,e nga reo,e nga karangaranga maha tae noa ki nga Minita o te Karauna. ko tenei te honore,hei tuku atu nga moemoea o ratou i kawea te kaupapa nei. huri noa ki a ratou kua wheturangitia ratou te hunga tautoko i kokiri,i mau ki te kaupapa,mai te timatanga,tae noa ki te puawaitanga o tenei ripoata. ahakoa kaore ano ki a kite ka tangi,ka mihi,ka poroporoakitia ki a ratou. ki era o nga totara o Te-Wao-nui-a-Tane,ki a Te Makarini,ki a Horomona ma ki a koutou kua huri ki tua o te arai haere,haere,haere haere i runga i te aroha,me nga roimata o matou kua mahue nei. e kore koutou e warewaretia. ma te Atua koutou e manaaki,e tiaki ka huri Contents Letter of Transmittal _____________________________________________________xiii 1. Summary 1.1 Background ________________________________________________________1 1.2 Historical Claims ____________________________________________________4 1.3 Contemporary Claims ________________________________________________9 1.4 Preliminary Claims __________________________________________________11 1.5 Rekohu, the Chatham Islands, or Wharekauri? _____________________________12 1.6 Concluding Remarks ________________________________________________13 2. -

QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021

Building Together • Hanga Ngātahi QUARTERLY INFRASTRUCTURE REFERENCE GROUP UPDATE Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 QUARTERLY IRG UPDATE 2 Q1: to 31 MARCH 2021 IRG PROGRAMME OVERVIEW .....................................3 PROGRESS TO DATE ................................................4 COMPLETED PROJECTS THIS QUARTER ...........................5 REGIONAL SUMMARY .............................................6 UPDATE BY REGION NORTHLAND ........................................................8 AUCKLAND .........................................................9 WAIKATO ...........................................................10 BAY OF PLENTY ....................................................11 GISBORNE ..........................................................12 HAWKE’S BAY ......................................................13 TARANAKI ..........................................................14 CONTENTS MANAWATŪ-WHANGANUI ........................................15 WELLINGTON .......................................................16 TOP OF THE SOUTH ................................................17 WEST COAST .......................................................18 CANTERBURY .......................................................19 OTAGO ..............................................................20 SOUTHLAND ........................................................21 NATIONWIDE .......................................................22 FULL PROJECT LIST ................................................23 GLOSSARY ..........................................................31 -

Reasons to Visit The

Reasons to visit the First place in the world to greet the new dawn Home of unique Chatham Islands birds and plants Visit significant sites of history and heritage Learn about the ancient Moriori covenant of peace Go fishing and hunting Enjoy rugged and awe inspiring landscapes Meet the people of the Chatham Islands Top 20 “Must See” Attractions Admiral Gardens & Pitt Island Kahukura Studio Point Munning Seal Colony Awatotara Bush Coastal Walking Track Port Hutt Basalt Columns Stone Cottage Chatham Cottage Crafts Sunderland Flying Boat Chatham Island Food Co. Taiko Camp and Gap Sanctuary Chatham Islands Museum Tommy Solomon Eva-Cherie Artz & Memorial Statue Studio 44°s Waitangi West Fishing Charters Wharekauri Station and Kaingaroa Splatter Rock chathamislands.co.nz Kopinga Marae DOC Walks Splatter/Taniwha Rock Skirmish Bay Stay " Wharekauri The Landing Ponga Whare Sunderland Flying Boat Maunganui Stone Cottage Ocean Mail Scenic Reserve Waitangi West " Point Munning " N KAIWHATA RD Conservation Covenant O Kaingaroa PORT R Seal Colony HU T Nikau Bush Port TT RD H R Conservation Area Te Whakaru Graveyard Hutt D " German Missionaries Settlement Basalt Columns Go Wild Nursery Thomas Currell J M Barker (Hapupu) Port Hutt Bay Stays Admiral Garden & Kahukura Studio AIRBASE RD National Historic Reserve Henga Lodge Te Whanga Henga Scenic Reserve Lagoon Chatham Island (R kohu / Wh arekauri) Tikitiki Hill Conservation Area " Chatham Island Charters Te One Pitt Island is Lake Pitt Island Guided Access Only " Huro " Te Matarae Kopinga Marae (Rangihaute/Rangiauria) -

Adsorption of Colour from Pulp and Paper Mill Wastewaters Onto Diatomaceous Earths

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Adsorption of Colour from Pulp and Paper Mill Wastewaters onto Diatomaceous Earths A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Chemistry at The University of Waikato by Shane B Carter 2007 © 2007 Shane B Carter II Abstract Production of pulp and paper from raw wood involves the washing of substantial quantities of highly coloured material from the wood pulp. Although most of this colour is trapped within the mill and the mills wastewater treatment system, discharge of coloured wastewater remains a problem of public concern. Lake Rotorua, New Zealand is filled with sediment consisting almost exclusively of diatoms. The most abundant species, Aulacoseira, has been shown to have very small pores (< 200 nm) that could be very useful for the capture and holding of large organic molecules.