Attended Deaths at Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yokohama Reinventing the Future of a City Competitive Cities Knowledge Base Tokyo Development Learning Center

COMPETITIVE CITIES FOR JOBS AND GROWTH CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized YOKOHAMA REINVENTING THE FUTURE OF A CITY COMPETITIVE CITIES KNOWLEDGE BASE TOKYO DEVELOPMENT LEARNING CENTER October 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2017 The World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved. This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The World Bank Group refers to the member institutions of the World Bank Group: The World Bank (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development); International Finance Corporation (IFC); and Multilater- al Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which are separate and distinct legal entities each organized under its respective Articles of Agreement. We encourage use for educational and non-commercial purposes. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Directors or Executive Directors of the respective institutions of the World Bank Group or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guaran- tee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Rights and Permissions This work is a product of the staff of the World bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waive of the privileges and immunities of the World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Contact: World Bank Group Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice Tokyo Development Learning Center (TDLC) Program Fukoku Seimei Bldg. -

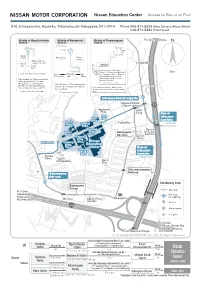

Map(Access by Train/Bus)

Nissan Education Center Access by Bus or on Foot 910, Ichisawa-cho, Asahi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa 241-0014 Phone 045-371-5523 (Area General Affairs Office) 045-371-5334 (Front desk) Vicinity of Higashi-totsuka Vicinity of Wadamachi Vicinity of Futamatagawa ForFor Shin-yokohamaShin-yokohama N Station Station Station Drugstore 2 1 North Exit 2 1 Ticket gate South Exit Book store BookstoreBookstore Super market Stand-and-eat soba noodle bar LAWSONLAWSON West 2 upstairs Exit Ticket gate 1 Take the bus for "Sakonyama Dai-go", or "Sakonyama Dai-roku", 50m East Exit (For Aurora City) ForFor TicketTicket ForFor or "Tsurugamine Eki", or "Higashi- YokohamaYokohama gategate EbinaEbina totsuka Eki Nishi-guchi" at the Take the bus for "Sakonyama keiyu Futamatagawa Station South Exit bus stop No.1. Futamatagawa Eki","Ichisawa * Leaves every 10 min. Shogakkou", or "Sakonyama Take the bus for "Shin-sakuragaoka Dai-ichi" at the Higashi-Totsuka Danchi" at the Wadamachi Station Station West Exit bus stop No.2. Depending on the time, traffic can be bus stop No.1. heavily congested. Please allow enough * Leaves every 20 to 30 min. * Leaves every 20 min. time. Ichisawa Danchi Iriguchi IIchisawachisawa DDanchianchi HHigashi-gawaigashi-gawa 17 AApartmentpartment HHACAC BBldgldg . DDrugrug Kan-ni EastEast Ichisawa- EastEast gategate Bldg.Bldg. kamicho NorthNorth FamilyMartFamilyMart Bldg.Bldg. CentralCentral (Inbound)(Inbound) Bldg.Bldg. TrainingTraining Kan-niKan-ni WestWest Bldg.Bldg. SakonyamaSakonyama Ichisawa-Ichisawa- Bldg.Bldg. No.3No.3 Dai-rokuDai-roku kamichokamicho TrainingTraining Dai-ichiDai-ichi Bldg.Bldg. ParkPark MainMain gategate TTrainingraining No.2No.2 NissanNissan Bldg.Bldg. EEducationducation NNo.1o.1 CCenterenter Kan-ni TrainingTraining Bldg.Bldg. -

HAKONE-YUMOTO / TONOSAWA Khakone Yumoto Hotel Bus on Foot Hakone =Hakoneji Kaiun 箱根路開雲 Shrine 35Min

INN/HOTEL Approximate travel times for major Hakone tourist spots A \Aura Tachibana あうら橘 B 7Bansuiro Fukuzumi 萬翠楼 福住 Hakone Tozan Railway Cable car Hakone Ropeway Hakone Ropeway Togendai F cFukuzumiro 福住楼 Owakudani Gora Sounzan (Lake Ashinoko) G [Gyokutei 玉庭 40min. 10 min. 8min. 16 min. H ]Hakone Airu 箱根 藍瑠 Bus Komagatake Ropeway oHakone Kamon 箱根花紋 (Owakudani) Komagatake 60min. Hakone-en 7min. 4Hakone Suimeisou 箱根水明荘 箱根湯本ホテル HAKONE-YUMOTO / TONOSAWA kHakone Yumoto Hotel Bus on foot Hakone =Hakoneji Kaiun 箱根路開雲 Shrine 35min. Motohakone-ko 15 min. aHatago Kintoen 旅籠 きんとうえん 'Hotel HATSUHANA ホテルはつはな Bus on foot Hakone Sekisho Hakone-Yumoto Station 6Hotel KAJIKASO ホテル河鹿荘 Checkpoint 40min. Hakone Sekisho-ato 2min. Area Map pHotel Maille Coeur Shougetsu ホテルマイユクール祥月 bus stop iHotel Nanpuso ホテル南風荘 uHotel Okada ホテルおかだ lHotel Okuyumoto ホテルおくゆもと eHotel Senkei ホテル仙景 Tonosawa Sta. INN / HOTEL / DAY SPA I /Ichinoyu Honkan 一の湯 本館 gItoen Hotel Hakone Yumoto 伊東園ホテル箱根湯本 Ichinoyu Honkan J rJapanese-style hotel Hakone Pax Yoshino 箱根パークス吉野 Deyama Hakone-Yumoto Sta. Railway bridge Motoyu Kansuiro to Miyanoshita, Ashinoko Tonosawa 1 Hakone Yuryo K 1Kappa Tengoku かっぱ 天 国 Yumoto-ohashi Shiunso ;Kijitei Hoeiso 雉子亭 豊栄荘 Deyama Hakone-Yumoto Sta. Sanmaibashi n Kinnotake Tonosawa Bridge Hayakawa Riv. to Odawara nKinnotake Tonosawa 金乃竹塔ノ澤 Tamano-o Chitose bashi Bridge -Kisenso 喜仙荘 m / bashi Kappa Tengoku 1 YAMA NO CHAYA Bridge Ajisaibashi Sanmaibashi Bridge Momiji bashi Hakone-Yumoto Sta. M zMamane Yu Masutomi Ryokan ままね湯ますとみ旅館 . Sakura Bridge Bridge b bashi 3 vMangoku -

Hosoya & Co., Ltd

In the company introductions, the numbers listed next to “Available in” and “Target market” correspond to the items listed below. 1: Establishment of manufacturing bases 2: Manufacturing and processing contracts with local companies 3: Technological partnerships with local companies 4: Establishment of research and development bases 5: Establishment of sales bases (including distribution contracts) 6: Exports(including exports through domestic trading companies) 7: Imports Contents P. 1-2 Introduction of Kanagawa Prefecture’s policy toward bio-related industries P. 3-27 Introduction of bio and medical-care-related companies Product Category Name of Company and Head Office Address Page Medical tools Job Corporation Yokohama City 3 Yamanouchi Co., Ltd. Yokohama City 3 Kobayashi Precision Industry Co., Ltd Sagamihara City 4 JMC Corporation Yokohama City 4 Yuki Precision Co., Ltd. Chigasaki City 5 Global Health Co., Ltd. Sagamihara City 5 Syouwa Precision Instrument Inc. Sagamihara City 6 Ikenkogyo Co. Ltd. Sagamihara City 6 Furukawa Techno Material Co., Ltd. Hiratsuka City 7 Horiuchi Woodcraft Oi-Machi 7 Pharmaceuticals TagCyx Biotechnologies Yokohama City 8 Riken Genesis Co., Ltd. Yokohama City 8 Yokohama Bioresearch & Supply, Inc. Yokohama City 9 GenoDive Pharma Inc. Isehara City 9 BioMedCore Inc. Yokohama City 10 Immunas Pharma, Inc. Kawasaki City 10 OncoTherapy Science, Inc. Kawasaki City 11 Nanoegg Research Laboratories, Inc. Kawasaki City 11 GSP Lab., Inc. Kawasaki City 12 GeneCare Research Institute Co., Ltd. Kamakura City 12 Samples and reagents for ReproCELL Yokohama City 13 research use Kabushiki Kaisha Dnaform Yokohama City 13 Scivax Corporation Kawasaki City 14 NanoDex Inc. Fujisawa City 14 Bioelectronics System Biotics Corporation Sagamihara City 15 Kyodo International, Inc. -

Rapid Range Expansion of the Feral Raccoon (Procyon Lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and Its Impact on Native Organisms

Rapid range expansion of the feral raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and its impact on native organisms Hisayo Hayama, Masato Kaneda, and Mayuh Tabata Kanagawa Wildlife Support Network, Raccoon Project. 1-10-11-2 Takamoridai, Isehara 259-1115, Kanagawa, Japan Abstract The distribution of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) was surveyed in Kanagawa Prefecture, central Japan. Information was collected mainly through use of a questionnaire to municipal offices, environment NGOs, and hunting specialists. The raccoon occupied 26.5% of the area of the prefecture, and its distribution range doubled over three years (2001 to 2003). The most remarkable change was the range expansion of the major population in the south-eastern part of the prefecture, and several small populations that were found throughout the prefecture. Predation by feral raccoons on various native species probably included endangered Tokyo salamanders (Hynobius tokyoensis), a freshwater Asian clam (Corbicula leana), and two large crabs (Helice tridens and Holometopus haematocheir). The impact on native species is likely to be more than negligible. Keywords: Feral raccoon; Procyon lotor; distribution; questionnaire; invasive alien species; native species; Kanagawa Prefecture INTRODUCTION The first record of reproduction of the feral raccoon presence of feral raccoons between 2001 and 2003 in Kanagawa Prefecture was from July 1990, and it and the reliability of the information. One of the was assumed that the raccoon became naturalised in issues relating to reliability is possible confusion with this prefecture around 1988 (Nakamura 1991). the native raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides; Damage by feral raccoons is increasing and the Canidae), which has a similar facial pattern with a number of raccoons, captured as part of the wildlife black band around the eyes, and a similar body size to pest control programme, is also rapidly increasing. -

Regional Distribution of Allergic Tree Pollen in Japan

hy & rap Na g tu o r e a Kishikawa et al., J Geogr Nat Disast 2016, S6 G l f D o i s l a Journal of DOI: 10.4172/2167-0587.S6-003 a s n t r e u r s o J ISSN: 2167-0587 Geography & Natural Disasters ResearchShort Communication Article OpenOpen Access Access Regional Distribution of Allergic Tree Pollen in Japan Reiko Kishikawa1,6*, Eiko Koto1, Chie Oshikawa1, Akemi Saito2, Norio Sahashi3,6, Nobuo Soh4, Toshitaka Yokoyama5, Tadao Enomoto6, Atsushi Usami6, Toru Imai6, Koji Murayama6, Yuma Fukutomi2, Masami Taniguchi2,Terufumi Shimoda1 and Tomoaki Iwanaga1 1The National Hospital Organization Fukuoka Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan 2The National Hospital Organization Sagamihara Hospital, Sagamihara, Japan 3Toho University, Funabashi, Japan 4Soh ENT clinic, Fukuoka, Japan 5Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan 6NPO Association of Pollen Information, Tokyo, Japan Keywords: Tree pollen allergy; Japanese Cedar/cypress family; Beech important pollen from start to end of pollen grains dispersing term all and Birch family; Oral allergic syndrome Japan Island. English J F M A M J J A S O N D Short Communication name In Japan patients with Japanese Cedar (JC) pollinosis have increased Pine * *** *** * nation widely since the latter of 1970’s. Japanese Governments has Endl * ** begun to take preventive measures against JC pollinosis and airborne Himalayan *** Cedar pollen monitoring has been begun to investigate as a causative agent Japanese *** *** ** * * since 1986. We have estimated the longitudinal investigation result for Cedar effective prevention and treatment against pollinosis in Japan. Cypress * *** * Family Method Ginkgo ** We have monitored airborne pollen all year around since July 1986 Willow * * * by gravitational pollen sampler, Durham’s sampler, at 15 locations for Birch Family *** *** *** *** long time in Japan Island. -

Chigasaki Breeze No 78 WINTER EDITION | December 2019 - February 2020 One for All, All for One: Why We Are Crazy About Hakone Ekiden

International Association of Chigasaki (IAC) Chigasaki Breeze No 78 WINTER EDITION | December 2019 - February 2020 One for All, All for One: Why We are Crazy about Hakone Ekiden Photo: Makiko Sato Every new year holiday in Chigasaki, many people tions, and each runner runs his section and passes off line the streets along the coastal road on Route 134 to a team sash called a tasuki to the next runner. watch the Tokyo-Hakone Round-Trip College In the Ekiden, an individual overall “winner” does not Ekiden Race (Hakone Ekiden), a two-day, round-trip exist. This sport is all about the teams. The team posi- race annually held between Tokyo and Hakone. They tions keep shuffling, and it gives every section its own cheer on their favorite teams, raising school banners drama. Passing tasuki from one section to another is and waving flags along the road. more important than anything to the runners. Tasuki The 218 km Hakone Ekiden is the longest and most are a heavy emotional load. Every runner must keep a important relay race in Japan. On Jan. 2, runners head balance between the appetite for winning and the risk from sea-level central Tokyo up to Lake Ashi on top of of going too hard and letting the team down. Runners’ Mt. Hakone, then run back the following day. passion for the Ekiden and love for their teams always The race has its origins in the communication system bring dramatic moments every year. of delivering messages from one place to another that The young athletes run through the business district was created in the Nara era (710-794 A.D). -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF SEPTEMBER 2017 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5128 025024 ATSUGI JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 44 0 0 1 0 1 45 5128 025026 EBINA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 15 0 0 0 0 0 15 5128 025027 ENZAN JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 29 0 0 0 0 0 29 5128 025028 FUJISAWA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 45 0 0 0 -1 -1 44 5128 025029 FUJISAWA SHONAN JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 53 0 0 0 0 0 53 5128 025030 FUJIYOSHIDA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 42 3 0 0 -3 0 42 5128 025031 HAKONE JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 36 1 0 0 0 1 37 5128 025032 HADANO JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 48 2 0 0 -1 1 49 5128 025033 HIRATSUKA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 40 0 0 0 0 0 40 5128 025034 HIRATSUKA NADESHIKO JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 13 1 0 0 0 1 14 5128 025035 ICHIKAWADAIMON MITAMA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 5128 025036 FUEFUKI JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 5128 025037 ISEHARA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 61 2 1 0 0 3 64 5128 025038 IZU OSHIMA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 20 0 0 0 -1 -1 19 5128 025040 KAMAKURA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 5128 025042 KAWASAKI NAKAHARA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 20 1 0 0 -1 0 20 5128 025043 KAWASAKI AOI JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 46 0 0 0 0 0 46 5128 025044 KAWASAKI JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 40 0 0 0 -1 -1 39 5128 025046 KAWASAKI MIYUKI JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 14 5 0 0 0 5 19 5128 025047 KAWASAKI TAJIMA JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 5128 025048 KAWASAKI CHUO JAPAN 330 B 4 09-2017 12 0 -

Open and Cheerful and Japanese, Successfully Understanding Each Other’S Culture, Which I Really Think Was Wonderful

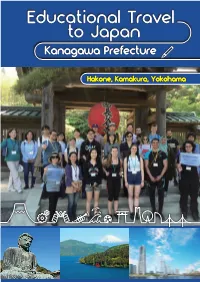

01 Sapporo Overview of Kanagawa Prefecture Located to the south of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture has a population of about 9.1 million, which Nagoya is the second largest in Japan following Tokyo Prefecture. We not only boast flourishing industries, Tokyo Kyoto such as automobiles and robotics, but are also blessed with abundant nature, being surrounded by the ocean and mountains.We have rich contents in various fields, including learning and Fukuoka Osaka experiencing contents necessary for school trips focusing on “industries,” “history,” “culture and Kanagawa art,” “nature,” and “sports,” as well as tourism contents. We are also easily accessible from both major gateways to Tokyo, Haneda and Narita airports, as well as from other major cities in Japan, including Tokyo and Osaka, with highly-developed public transit systems and expressways. Okinawa Offering rich contents and an opportunity to stay in Japan safely and securely, we are looking forward to your visit to Kanagawa Prefecture. Chiba Access (Approx. time) Train Bus / Car Haneda Airport → Yokohama 23min. 30min. Narita Airport → Yokohama 90min. 90min. Tokyo → Yokohama 25min. 50min. Yokohama → Kamakura 30min. 50min. Yokohama → Hakone 80min. 90min. Kamakura → Hakone 75min. 75min. TDR → Yokohama 60min. 60min. Contents Overview of Kanagawa Prefecture 02-03 History 16-18 School events in Kanagawa Prefecture 04-05 Culture and Art 19-22 School Exchange Programs 06-07 Nature 23-25 Home Stay, etc. 08-09 Sport 26-27 Facility Map 10-11 Recommended Routes/ 30-31 Inquiry Industrial Tourism 12-15 02 03 *Since these events vary for different schools, please contact a school of your interest in advance. -

Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone

MAY 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone ALSO: M83 Interview, Sake Beauty Secrets, Faces of Tokyo’s LGBT Community, Hiromi Miyake Lifts for Gold, Best New Restaurants 2 | MAY 2016 | TOKYO WEEKENDER 7 17 29 32 MAY 2016 guide radar 26 THE FLOWER GUY CULTURE ROUNDUP THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS Nicolai Bergmann on his upcoming shows and the impact of his famed flower boxes 7 AREA GUIDE: EBISU 41 THE ART WORLD Must-see exhibitions including Ryan McGin- Already know the neighborhood? We’ve 28 JUNK ROCK ley’s nudes and Ville Andersson’s “silent” art thrown in a few new spots to explore We chat to M83 frontman Anthony Gon- zalez ahead of his Tokyo performance this 10 STYLE WISH LIST 43 MOVIES month Three films from Japanese distributor Gaga Spring fashion for in-between weather, star- that you don’t want to miss ring Miu Miu pumps and Gucci loafers 29 BEING LGBT IN JAPAN To celebrate Tokyo Rainbow Pride, we 12 TRENDS 44 AGENDA invited popular personalities to share their Escape with electro, join Tokyo’s wildest mat- Good news for global foodies: prepare to experiences suri, and be inspired at Design Festa Vol. 43 enjoy Greek, German, and British cuisine 32 BEAUTY 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES The secrets of sake for beautiful skin, and Dewi and her dogs hit Yoyogi and Leo in-depth Andaz Tokyo’s brand-new spa menu COFFEE-BREAK READS DiCaprio comes to town 17 HAKONE TRAVEL SPECIAL 34 GIRL POWER 50 BACK IN THE DAY Our nine-page guide offers tips on what to Could Hiromi Miyake be Japan’s next This month in 1981: “Young Texan Becomes do, where to stay, and how to get around gold-winning weightlifter? Sumodom’s 1st Caucasian Tryout” TOKYO WEEKENDER | MAY 2016 | 3 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER Easier navigation Keep an eye out for MAY 2016 a new set of sections that let you, the MAY 2016 reader, have a clear set of what’s going where. -

Mitsubishi Electric Completes New Satellite Component Production Facility Will Help to Strengthen Company’S Growing Foothold in Global Satellite Market

MITSUBISHI ELECTRIC CORPORATION PUBLIC RELATIONS DIVISION 7-3, Marunouchi 2-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 100-8310 Japan FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 3115 Customer Inquiries Media Inquiries Space Systems Public Relations Division Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Mitsubishi Electric Corporation www.MitsubishiElectric.com/ssl/contact/bu/ [email protected] space/form.html www.MitsubishiElectric.com/news/ Mitsubishi Electric Completes New Satellite Component Production Facility Will help to strengthen company’s growing foothold in global satellite market TOKYO, June 1, 2017 – Mitsubishi Electric Corporation (TOKYO: 6503) announced today that it has completed construction of a facility that will double the satellite component production capacity of its Kamakura Works’ Sagami Factory in Sagamihara, Japan. The new facility, Mitsubishi Electric’s core production and testing site for solar array panels, structural panels and other satellite components, is expected to help grow Mitsubishi Electric’s share of the global satellite market once production starts this October. Rendition of new facility at Sagami Factory Mitsubishi Electric is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of satellite components, most notably structures made with advanced composite materials for the global market. The company has a rich history of providing global satellite manufacturers with solar array panels, structural panels and antennas produced at its Kamakura Works. Over the years, Mitsubishi Electric has developed a substantial share of this market. 1/3 The new facility will introduce a number of advanced manufacturing machines, such as high-precision machining equipment and automated welding machines, which will help the factory to double its production capacity. Existing machines currently dispersed throughout the factory will be concentrated in the new facility. -

Saitama Prefecture Kanagawa Prefecture Tokyo Bay Chiba

Nariki-Gawa Notake-Gawa Kurosawa-Gawa Denu-Gawa Nippara-Gawa Kitaosoki-Gawa Saitama Prefecture Yanase-Gawa Shinshiba-Gawa Gake-Gawa Ohba-Gawa Tama-Gawa Yana-Gawa Kasumi-Gawa Negabu-Gawa Kenaga-Gawa Hanahata-Gawa Mizumotokoaitame Tamanouchi-Gawa Tobisu-Gawa Shingashi-Gawa Kitaokuno-Gawa Kita-Gawa Onita-Gawa Kurome-Gawa Ara-Kawa Ayase-Gawa Chiba Prefecture Lake Okutama Narahashi-Gawa Shirako-Gawa Shakujii-Gawa Edo-Gawa Yozawa-Gawa Koi-Kawa Hisawa-Gawa Sumida-Gawa Naka-Gawa Kosuge-Gawa Nakano-Sawa Hirai-Gawa Karabori-Gawa Ochiai-Gawa Ekoda-Gawa Myoushoji-Gawa KItaaki-Kawa Kanda-Gawa Shin-Naka-Gawa Zanbori-Gawa Sen-Kawa Zenpukuji-Gawa Kawaguchi-Gawa Yaji-Gawa Tama-Gawa Koto Yamairi-Gawa Kanda-Gawa Aki-Kawa No-Gawa Nihonbashi-Gawa Inner River Ozu-Gawa Shin-Kawa Daigo-Gawa Ne-Gawa Shibuya-Gawa Kamejima-Gawa Osawa-Gawa Iruma-Gawa Furu-Kawa Kyu-Edo-Gawa Asa-Kawa Shiroyama-Gawa Asa-Gawa Nagatoro-Gawa Kitazawa-Gawa Tsukiji-Gawa Goreiya-Gawa Yamada-Gawa Karasuyama-Gawa Shiodome-Gawa Hodokubo-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Diversion Channel Minami-Asa-Gawa Omaruyato-Gawa Yazawa-Gawa Jukuzure-Gawa Meguro-Gawa Yudono-Gawa Oguri-Gawa Hyoe-Gawa Kotta-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Annai-Gawa Kuhonbutsu-Gawa Tachiai-Gawa Ota-Gawa Shinkoji-Gawa Maruko-Gawa Sakai-Gawa Uchi-Kawa Tokyo Bay Tsurumi-Gawa Aso-Gawa Nomi-Kawa Onda-Gawa Legend Class 1 river Ebitori-Gawa Managed by the minister of land, Kanagawa Prefecture infrastructure, transport and tourism Class 2 river Tama-Gawa Boundary between the ward area and Tama area Secondary river.