Saba Management Success Data Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plum Piece Evidence for Archaic Seasonal Occupation on Saba, Northern Lesser Antilles Around 3300 BP Corinne L

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2003 ISSN 1524-4776 Plum Piece Evidence for Archaic Seasonal Occupation on Saba, Northern Lesser Antilles around 3300 BP Corinne L. Hofman Menno L.P. Hoogland Recent investigations on the island of Saba, northern Lesser Antilles, revealed evidence of preceramic occupation in the northwestern part of the island at an elevation of approxinately 400 m above sea level. The inland location of dense midden deposits in a tropical forest environment makes the Plum Piece site unique for studying the preceramic occupation of the Antilles, a period that is otherwise mainly known from coastal settings. The recovered artifacts and the radiocarbon dates support an attribution to the Archaic period of the preceramic Age. The nature of the tools and the restricted number of exploited food sources suggest a temporary, probably seasonal, occupation of the site for a unique activity. _____________________________________ Archaeological investigations on the island coastal exploitation in which shellfish of Saba, northern Lesser Antilles (Figure 1) predominates. The species collected are related during the summers of 2001 and 2002 revealed to the exploitation of specific coastal evidence of preceramic occupation at the site of environments, varying from mangroves to Plum Piece in the northwestern part of the island shallow-water and shallow-reef habitats. dating from approximately 3300 BP. Prior to these investigations a preceramic date of 3155± The atypical location of the site of Plum 65 BP had been obtained from the Fort Bay area Piece in the tropical forest area of Saba at an in the northeastern sector of Saba (Roobol and elevation of 400 m above sea level provides Smith 1980). -

Parent /Guardian & Student Booklet 2019- 2020

PARENT /GUARDIAN & STUDENT BOOKLET 2019- 2020 Address: Pasture Road 9 St. John’s Saba , Dutch Caribbean Tel/Fax: +599 416 3281 Email: [email protected] Website: http:// www.sabasacredheartschool.com This handbook has been written with the purpose of being a reference for parents. We have endeavored to share basic information on the structure and management of our school. It is our hope that you will familiarize yourself with the content for the new school year. 1 Welcome to Sacred Heart School Proverbs 22:6 Start children off on the way they should go, and even when they are old, they will not turn from it. Dear Parents/ Guardians, I bid you all a warm welcome back to school. I trust that everyone had a wonderful summer break and are all ready for the new academic schoolyear 2019-2020. I would like to welcome all new staff members, parents and students. As a school we hope that you will take the time to read this parent guide carefully for it contains perti- nent information that you will need to know. The following quote states: “Education begins at home and we applaud the parents who recognize that: they-not someone else- must take the responsibility to assure that their children are well educated.” In order for us to have a very respectful, safe, and productive learning environment we will be expect- ing you the parents to support us with the following: Stay in regular communication with the school. Show an active interest in your child’s school work, progress and homework Help your child to be prepared for school (a good breakfast, a healthy lunch, all the needed school ma- terials in their schoolbag) Make sure your child attends school regularly and on time and notify the school on time when the child is absent Know the bus, school, and class rules Assist your child in following the rules of behavior Assist school staff with disciplinary issues involving your child I trust that with the help of God we will achieve our goal. -

Chapter 6: Excavated Non-Plantation Contexts

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/45747 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Espersen, R. Title: “Better than we”: landscapes and materialities of race, class, and gender in pre- emancipation colonial Saba, Dutch Caribbean Issue Date: 2017-02-09 Page | 214 Chapter 6: Excavated non-Plantation Contexts This chapter will describe the sites across Saba that will be referenced throughout this work. The process of excavation will be described along with details of artifact compositions. Unless otherwise specified, all sites discussed below which range between SB 001 to SB 032 were originally surveyed by Jay Haviser (1985). Particular attention was paid to the ceramic assemblages regarding typologies and surface decoration, and to a lesser extent the glass assemblage, in the cases where this abounded relative to ceramics. SB 037: The Fort Bay ridge site Overview and Site Location The site SB 037 is located at the foot of Bunker Hill in the southwest of the island at approximately 17°37’07N and 63°15’04W, half way up the road between the Fort Bay Harbour and The Bottom. Its proximity to Parish Hill and Great Hill, two young volcanic domes, may have impacted its pre-Columbian occupation history through volcanic events. The vegetation at SB 037 consists mainly of grasses, the invasive Euphorbia tithymaloides, and “Maraun bush” (Croton flavens L.). The SB 037 site was a strategic settlement location throughout the Amerindian and colonial periods. Fort Bay, Ladder Bay, and Wells Bay are the only reliable anchorage points on Saba, aided in part by the sheltered position of the western waters around Saba from the northeast trade winds. -

Saba National Marine Park the Kingdom of the Netherlands

UNITED NATIONS EP United Nations Original: ENGLISH Environment Program Proposed areas for inclusion in the SPAW list ANNOTATED FORMAT FOR PRESENTATION REPORT FOR: Saba National Marine Park The Kingdom of the Netherlands Date when making the proposal : 7/7/14 CRITERIA SATISFIED : Ecological criteria Cultural and socio-economic criterias Representativeness Productivity Conservation value Cultural and traditional use Rarity Socio-economic benefits Naturalness Critical habitats Diversity Connectivity/coherence Resilience Area name: Saba National Marine Park Country: The Kingdom of the Netherlands Contacts Last name: HOETJES First name: Paul Focal Point Position: Policy Coordinator Nature Email: [email protected] Phone: (+599) 715 83 08 Last name: Wulf First name: Kai Manager Position: Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: 5994163295 SUMMARY Chapter 1 - IDENTIFICATION Chapter 2 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Chapter 3 - SITE DESCRIPTION Chapter 4 - ECOLOGICAL CRITERIA Chapter 5 - CULTURAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CRITERIA Chapter 6 - MANAGEMENT Chapter 7 - MONITORING AND EVALUATION Chapter 8 - STAKEHOLDERS Chapter 9 - IMPLEMENTATION MECHANISM Chapter 10 - OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION ANNEXED DOCUMENTS Attachment 1 Leeward Islands map Attachment 2 SNMP Management Plan 1999 Attachment 3 Buchan 1998 Saba Report Attachment 4 Economic and social Study Attachment 5 Volcanology Attachment 6 Dr J Rahn Seamount Maps Attachment 7 Tourism Plan Attachment 8 Legislation Attachment 9 Zone maps Attachment 10 Physical resources Attachment 11 Socio economic study Attachment 12 Conservation Species Attachment 13 Marine Mammals Attachment 14 Debrot 2013 Whale Shark observations Attachment 15 Bathymetry Attachment 16 Bak 1977 Coral reef zonation Attachment 17 Important Bird Areas Attachment 18 SCF dive brochure Attachment 19 Integrating economics Attachment 20 Monitoring review Attachment 21 Oil pollution Attachment 22 Status of reefs Attachment 23 CaMPAM capacity assessment 2011 Attachment 24 CARNARI management report. -

Saba's Nature Trails

Visitor Information Saba Conservation Foundation PO Box 18, The Bottom The Nature of Saba Saba, Netherlands Antilles www.sabapark.org The island of Saba forms part of the inner arc of islands stretching between the Virgin Islands and Venezuela. Saba is located within the Caribbean hurricane belt. The hurricane season starts in July and normally lasts until November. All of these islands are of volcanic origin resulting in an extremely mountainous topography. Saba is Temperature, humidity, and rainfall vary significantly with altitude on high volcanic islands such as Saba. The vegetation varies approximately 13 square kilometers (5 square miles) in area with Mt. Scenery as its highest elevation at 877m within distinctive zones which are also related to altitude and humidity. Several vegetation types exist on the island. Clouds often (2877ft) above sea level. The slopes of the peaks and domes are steep, in some places exceeding 60º. Several cover the top of Mt. Scenery, resulting in cloud-forest vegetation. Slightly lower in a belt where high rainfall occurs, rain-forest valleys or ravines locally known as guts run down the slopes of the mountain. A few level plateau can be vegetation is present. Still lower on the slopes where humidity decreases, the vegetation gradually becomes drier. Plants and trees found, the largest being the valley of The Bottom and Flat Point. found closer to shore often adapt to the salty environment, while species found at higher elevations would not survive at sea level. The average annual rainfall for Saba is about 1,000 mm (40 inch). Precipitation varies depending on elevation and exposure to the eastern trade winds. -

History-Of-Saba-J.-Hartog.Pdf

i ~ I i : ~ . I . j ' I - HIS~()Ry OF SABA by DR. J. HARTOG C~R 33!l~1 6~~· Saba, you rise from the Ocean, with mountains and hill-sides so steep ... PUBLISHED BY THE SABA ARTISAN FOUNDA TION SABA NETHERLANDS ANTILLES HIS~()Ry OF SABA by DR. J. HARTOG C~R 33!l~1 6~~· Saba, you rise from the Ocean, with mountains and hill-sides so steep ... PUBLISHED BY THE SABA ARTISAN FOUNDA TION SABA NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Indians dwelt on four sites The island of Saba in the Dutch Windward Islands of the Neth- erlands Antilles was first inhabited by Indians. At 2,296 feet above sea level there is a site known as Indian Camp which reminds us of this fact. In the last century arrowheads and spearheads were found there, and from the workmanship we can see that the makers were probably Caribs. Ist printing 1975 lid printing 1982 Busult adze found on Saba. This type of ornamented adze is foulld only in the • I'd printing 1988 Greater Antilles and the Bahamas, so it must have been brought to Saba. The adze is prese.rved in the State Museum of Ethnology in Leyden. The length is 73/4 inches (20 em). This edition has been financed by: Ovcrlegorgaan Kulturele Samenwerking Nederlandse Antillen (OKSNA), In 1858 a basalt adze was found on the island. The then gover- 'uragao. nor, Reinier F. C. van Lansberge, presented this to the Nether- lands Ethnological Museum of Leyden where it is still preserved. Translation by Frank Hassell. In 1923 Professor Dr. -

Volcanology of Saba and St. Eustatius Northern Lesser Antilles

I . , II III Volcanology of Saba and St. Eustatius, Northern Lesser Antilles M. John Roobol and Alan L. Smith , , IV Digital versions of the maps in this volume and other supporting materials are presented on the website of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, see www.knaw.nl/edita/antilles Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences P.O. Box , GC Amsterdam, the Netherlands T +-- F+-- E [email protected] www.knaw.nl --- The paper in this publication meets the requirements of « iso-norm () for permanence © Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. V Contents List of Plates XI Abstract XII Acknowledgments XVIII 1 Island Arcs of the eastern Caribbean 2 The composite arc of the Lesser Antilles 3 The Active Arc 3 The Extinct Arc of the Limestone Caribbees 5 The Aves Ridge 6 Venezuela and Grenada basins 7 Submarine banks of the northern Lesser Antilles 7 Anegada Passage 8 Kallinago Depression 9 Seismically active faults 9 Faults revealed by seismic reflection profiles 10 Lineaments 11 Drilling and seismic reflection studies on the Saba Bank 11 Mesozoic rocks of St. Croix and La Desirade islands 13 Mesozoic rocks dredged from submarine scarps on banks in the northeastern Caribbean 13 Discussion 14 VI Contents 17 Introduction 17 Development of pyroclastic studies in the Lesser Antilles 20 Classification of pyroclastic deposits of the Lesser Antilles 22 Pelean-style eruptions 23 St. -

IVM Institute for Environmental Studies the Tourism Value of Nature on Saba

IVM Institute for Environmental Studies The Tourism Value of Nature on Saba S. van de Kerkhof S.W. Schep P. van Beukering L. Brander Report R-14/08 17 March 2014 This report was commissioned by: Ministry of Economic Affairs, Netherlands IVM Wolfs Company office: Institute for Environmental Studies VU University Amsterdam Sabadeco West 230 De Boelelaan 1087 Santa Barbara 1081 HV AMSTERDAM Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands The Netherlands The Netherlands T +599 7883595 T +31-20-598 9555 E [email protected] F +31-20-598 9553 E [email protected] Copyright © 2014, Institute for Environmental Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright holder IVM Institute for Environmental Studies The Tourism Value of Nature on Saba Contents List of abbreviations 5 Summary 7 1 Introduction 9 2 Context of this study 11 2.1 Project framework and funding 11 2.2 Saba 13 2.3 Prior studies 15 3 Methodology 17 3.1 Theoretical background 17 3.2 Research method 18 3.3 Choice experiment design 19 3.4 Survey design 22 3.5 Procedure 22 3.6 Possible biases and challenges 23 4 Results 25 4.1 Visitor numbers 25 4.2 Representativeness 25 4.3 Visitor characteristics 27 4.4 Experience and activities 30 4.5 Perceived potential threats 32 4.6 Statements 33 4.7 Who is ‘in principle’ willing to pay for conservation? 35 4.8 Choice experiment results 37 4.9 Total tourism -

The Unspoiled Queen ‘The Unspoiled Queen’ Saba, Mysterie in Een Notendop

The Unspoiled Queen ‘The unspoiled queen’ Saba, mysterie in een notendop De 1.900 bewoners van Saba noemen hun Het is goed zoeken op de atlas naar het eiland Saba. Een eiland trots ‘The unspoiled queen’. minuscuul donkergroen stipje in de Caribische Zee. Groen, De ‘onbedorven koningin’ verdient deze titel. omdat het ook werkelijk groen is. In alle toonaarden zelfs. Het oppervlak van amper dertien Niet alleen vanwege de vegetatie, maar ook door het karakter vierkante kilometer wordt van het eiland en haar bewoners. Dichtbeboste flanken van bewoond, niet bevolkt. een vulkaan in ruste, rijzen tot meer dan achthonderd meter Het verschil is verademend. boven de zeespiegel uit. Zelfs als de hemel overal blauw kleurt, zweeft rond de top van ‘Mount Scenery’ altijd een mysterieus wolkendek. Saba is een bijzondere vakantiebestemming. Geen massa-toerisme, uitgebreide all-inclusive resorts of lange zandstranden. Wel een overweldigend mooie natuur, een fabelachtige onderwaterwereld en een bevolking die een extra dimensie toevoegt aan het begrip gastvrijheid. Omdat de beleving zo intens is. Saba ís ecotoerisme. De Sabanen zelf delen dit geheim het liefst alleen met gasten die oprecht kiezen voor de puurheid van het bestaan. 3 Geschiedenis en cultuur Een vulkaan waarvan de top 877 meter boven de zeespiegel uitsteekt. Dat is Saba. Columbus zag tijdens zijn ontdekkingsreis in 1493 niets in het piepkleine berglandschap. Lange tijd was het een komen en gaan van nieuwe heersers. Sinds 1816 behoort Saba definitief tot het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden. Eeuwenlang verdienden de Sabanen de kost met zeevaart en visserij. De bewoners hebben het eiland geheel op eigen kracht geschikt gemaakt voor bewoning. -

A Permanent, Real-Time Monitoring Network for the Volcanoes Mount Scenery and the Quill in the Caribbean Netherlands

geosciences Article A Permanent, Real-Time Monitoring Network for the Volcanoes Mount Scenery and The Quill in the Caribbean Netherlands Elske de Zeeuw-van Dalfsen * and Reinoud Sleeman R & D Department of Seismology and Acoustics, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), Utrechtseweg 297, 3731 GA De Bilt, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 July 2018; Accepted: 20 August 2018; Published: 27 August 2018 Abstract: The stratovolcanoes of Mt. Scenery at Saba and The Quill at St. Eustatius in the Caribbean Netherlands, with a total population of about 5200 people, are part of the active volcanic arc of the Lesser Antilles but lacked a multiparameter volcano and earthquake monitoring system until the beginning of 2018. The permanent seismic network on the islands has been built up since 2006 and was expanded in 2018 with one permanent Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) sensor at each volcano and a temperature logger on Saba. We provide technical details of all equipment and the installation procedures, and we show the preliminary results of GNSS data processing. Deploying a remote, permanent network of different sensor types under tropical island conditions and sustaining access to real-time high-quality data to monitor the state of volcanoes is an underappreciated challenge. Despite the problems encountered, we operated the network with an overall availability of 84.5% in the first half of 2018 compared to 70.3% in the years before. The main unresolved problem affecting seismic data quality is related to sudden out-of-balance seismometer mass positions. We provide a complete overview of our monitoring network, the various challenges encountered, and the solutions applied, and we address future plans. -

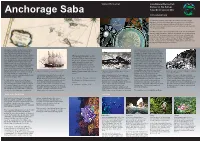

Yacht Front David.Eps

Visitor Information Saba National Marine Park PO Box 18, The Bottom Anchorage Saba Saba, Netherlands Antilles www.sabapark.org The Saba National Marine Park (SMP) was established in 1987 with the objective to preserve and manage Saba's marine resources. The SMP was not founded to repair a damaged environment but rather to ensure the continued quality of an extraordinary resource for the benefit and enjoyment of everyone in perpetuity. The SMP surrounds the entire island and extends from the high-water mark down to a depth of 60 metres (200 feet), including the seabed and overlying waters. The SMP is administered by the Saba Conservation Foundation, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to contribute to the development and preservation of Saba's natural and cultural heritage. The SMP raises revenue through visitor fees, souvenir sales and donations, and is one of the few self-sustaining marine parks in the world. Christopher Columbus sighted Saba during his the island became known as the 'Island of second voyage to the west on 13 November Women' during this period. In the early days of 1493. The island fell under Spanish rule for navigation, boats were built on Saba at Tent Bay almost 150 years, although according to Spanish and Wells Bay. Some weighed as much as 60 records, there is no indication that colonization 'We landed thereafter on the gross tons. Saba also had a navigation school, was ever attempted. It is assumed that during the island of Saba; there is a very founded by Capt. Frederick Simmons that started years of Spanish rule, ships passing Saba may large rock, where very large in 1909 and lasted until 1922. -

Small Island Treasures Often Overlooked, Laid-Back Saba and St

Small Island Treasures Often overlooked, laid-back Saba and St. Eustatius in the Dutch West Indies lure hikers and divers. By Richard Varr Trees rustled in the gentle Caribbean breeze, hovering over red-roofed cottages dotting a rolling landscape as it ascends cloud-shrouded Mount Scenery. The vegetation is lush—leafy palm trees, ferns, hanging orchids and giant, green elephant-ear leaves skirt hiking trails and winding roads. Roosters were already crowing as the sun rose, when the rustic town of Windwardside got its wakeup call. What sounded like a horn— breathy and bellowing— trumpeted from a hillside house surrounded by pineapple and breadfruit trees overlooking the town below. It blew once, twice, then three times and again. And again. The horn was a conch shell; the blower, Percy ten Holt, sounds off every morning at 6 a.m. sharp, except Sundays, on the small Dutch island of Saba. “I do it because it’s a tradition on Saba,” he said. “When I was a boy, there was a man named Peter, and he used to blow when a ship was coming. Everybody would get excited.” He acknowledged he first got in trouble with the neighbors, but now it’s just something everyone in Windwardside expects to hear at dawn’s first light. “I’ve been doing it for 34 years, and I feel proud doing it.” He called his view of Windwardside the “million-dollar view,” yet many vantage points from hilltops and hiking trails showcase ocean panoramas and the rugged shorelines of this 5-square-mile island with a population of about 2,000.