Mimbres Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Construction and Occupation of Unit 11 at Paquimé, Chihuahua

THE CONSTRUCTION AND OCCUPATION OF UNIT 11 AT PAQUIMÉ, CHIHUAHUA DRAFT (February 5, 2009), comments welcomed! David A. Phillips, Jr. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology Department of Anthropology MSC01 1050, 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131 USA Elizabeth Arwen Bagwell Desert Archaeology, Inc. 509 South 48th Street, Suite 104 Tempe, Arizona 85281 USA Abstract Understanding Paquimé’s internal development is important to regional prehistory, but the sheer amount of published data deters attempts to interpret the site’s construction history. The challenge can be reduced to a workable size by examining individual architectural units within the site. By way of illustration, a re-study of Unit 11 (House of the Serpent) indicates that its construction history may differ somewhat from the original published account. The approach used in the re-study is frankly experimental and is offered in the hope that others will be able to improve on it (or else prove its lack of utility). Three decades ago, in the most influential report ever prepared on northwest Mexican prehistory, Charles Di Peso and his colleagues described Paquimé (Di Peso 1974; Di Peso et al. 1974; see also Contreras 1985). Since then, the site’s construction history has received little detailed attention. Instead, recent discussions have focused on dating the site as a whole (End Note) or on the presence or absence of a multistory “east wing” (Lekson 1999a:80; 1999b; Phillips and Bagwell 2001; Wilcox 1999). In recent years, the most detailed studies of Casas Grandes construction have come from other Casas Grandes sites (Bagwell 2004; Kelley et al. -

The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N

MS-372 The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N. Fort Valley Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001 (928)774-5211 ext. 256 Title Harold Widdison Rock Art collection Dates 1946-2012, predominant 1983-2012 Extent 23,390 35mm color slides, 6,085 color prints, 24 35mm color negatives, 1.6 linear feet textual, 1 DVD, 4 digital files Name of Creator(s) Widdison, Harold A. Biographical History Harold Atwood Widdison was born in Salt Lake City, Utah on September 10, 1935 to Harold Edward and Margaret Lavona (née Atwood) Widdison. His only sibling, sister Joan Lavona, was born in 1940. The family moved to Helena, Montana when Widdison was 12, where he graduated from high school in 1953. He then served a two year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1956 Widdison entered Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, graduating with a BS in sociology in 1959 and an MS in business in 1961. He was employed by the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington DC before returning to graduate school, earning his PhD in medical sociology and statistics from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio in 1970. Dr. Widdison was a faculty member in the Sociology Department at Northern Arizona University from 1972 until his retirement in 2003. His research foci included research methods, medical sociology, complex organization, and death and dying. His interest in the latter led him to develop one of the first courses on death, grief, and bereavement, and helped establish such courses in the field on a national scale. -

The Native Fish Fauna of Major Drainages East of The

THE NATIVE FISH FAUNA OF MAJOR DRAINAGES EAST OF THE CONTINENTAL DIVIDE IN NEW MEXICO A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Biology Eastern New Mexico University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements fdr -the7Degree: Master of Science in Biology by Michael D. Hatch December 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction Study Area Procedures Results and Discussion Summary Acknowledgements Literature Cited Appendices Abstract INTRODUCTION r (t. The earliest impression of New Mexico's native fish fauna =Ems during the 1850's from naturalists attached to various government survey parties. Without the collections from these and other early surveys, the record of the native fish fauna would be severely deficient because, since that time, some 1 4 native species - or subspecies of fish have become extirpated and the ranges of an additionial 22 native species or subspecies have become severly re- stricted. Since the late Miocene, physiographical changes of drainages have linked New Mexico, to varying degrees, with contemporary ichthyofaunal elements or their progenitors from the Rocky Mountains, the Great Plains, the Chihuahuan Desert, the Mexican Plateau, the Sonoran Desert and the Great Basin. Immigra- tion from these areas contributed to the diversity of the state's native ichthyofauna. Over the millinea, the fate of these fishes waxed and waned in ell 4, response to the changing physical and _chenaca-l-conditions of the surrounding environment. Ultimately, one of the most diverse fish faunas of any of the interior southwestern states developed. Fourteen families comprising 67 species of fish are believed to have occupied New Mexico's waters historically, with strikingly different faunas evolving east and west of the Continental Divide. -

File1\Home\Cwells\Personal\Service

SAS Bulletin Newsletter of the Society for Archaeological Sciences Volume 28 number 4 Winter 2005 Archaeological Science The process involves rehydrating the eyes and optical on ‘All Hallows Eve’ nerves, preparing the tissues for chemical processing, embedding the tissues in paraffin, slicing the specimens for By the time you receive this issue of the SAS Bulletin, microscopic viewing, applying stains to highlight selected Celtic Samhain, as well as the pumpkin-studded American cellular characteristics, and finally examining the tissues under version called Halloween, will have passed. Still, in this season a microscope. of “days of the dead,” I’m inspired to share with you an interesting bit of archaeological science being conducted on— Tests were conducted for eye diseases, such as glaucoma you guessed it—mummies. and macular degeneration, but Lloyd says there are many more systemic ailments that can be found by examining the eyes. In late October, ophthalmologist William Lloyd of the “During modern-day eye exams we can see signs of diabetes, University of California-Davis School of Medicine dissected high blood pressure, various cancers, nutritional deficiencies, and examined the eyes of two north Chilean mummies for fetal alcohol syndrome and even early signs of HIV infection,” evidence of various diseases and medical conditions. One of said Lloyd. “These same changes are visible under the the eyes belonged to a Tiwanaku male who was 2 years old microscope.” when he died 1,000 years ago, and the other is from a Tiwanaku female, who was approximately 23 years old when she died This edition of the SAS Bulletin contains news about other 750 years ago. -

THE SMOKING COMPLEX in the PREHISTORIC SOUTHWEST By

The smoking complex in the prehistoric Southwest Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Simmons, Ellin A. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 00:29:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552017 THE SMOKING COMPLEX IN THE PREHISTORIC SOUTHWEST by Ellin A* Simmons A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 8 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library• Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: /// A- APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ^ 7 ' T. -

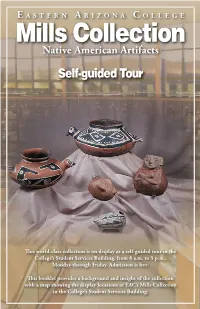

Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-Guided Tour

E ASTE RN A RIZONA C OLLEGE Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-guided Tour This world-class collection is on display as a self-guided tour in the College’s Student Services Building, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Admission is free. This booklet provides a background and insight of the collection with a map showing the display locations of EAC’s Mills Collection in the College’s Student Services Building. MillsHistory Collection of the rdent avocational archaeologists Jack Aand Vera Mills conducted extensive excavations on archaeological sites in Southeastern Arizona and Western New Mexico from the 1940s through the 1970s. They restored numerous pottery vessels and amassed more than 600 whole and restored pots, as well as over 5,000 other artifacts. Most of their work was carried out on private land in southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico. Towards the end of their archaeological careers, Jack and Vera Mills wished to have their collection kept intact and exhibited in a local facility. After extensive negotiations, the Eastern Arizona College Foundation acquired the collection, agreeing to place it on public display. Showcasing the Mills Collection was a weighty consideration when the new Student Services building at Eastern Arizona College was being planned. In fact, the building, and particularly the atrium area of the lobby, was designed with the Collection in mind. The public is invited to view the display. Admission is free and is open for self-guided tours during regular business hours, Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. -

TJ Ruin: Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico

GILA CLIFF DWELLINGS NATIONAL MONUMENT NEW MEXICO PETER J. MCKENNA JAMES E. BRADFORD SOUTHWEST CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER PROFESSIONAL PAPERS NUMBER 21 PUBLISHED REPORTS OF THE SOUTHWEST CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER 1. Larry Murphy, James Baker, David Buller, James Delgado, Rodger Kelly, Daniel Lenihan, David McCulloch, David Pugh; Diana Skiles; Brigid Sullivan. Submerged Cultural Resources Survey: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reves-Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1984. 2. Toni Carrell. Submerged Cultural Resources Inventory: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reves-Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1984. 3. Edwin C. Bearss. Resources Study: Lyndon B. Johnson and the Hill Country. 1937-1963. Division of Conservation, 1984. 4. Edwin C. Bearss. Historic Structures Report: Texas White House. Division of Conservation, 1986. 5. Barbara Holmes. Historic Resource Study of the Barataria Unit of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. Division of History, 1986. " 6. Steven M. Burke and Marlys Bush-Thurber. Southwest Region Headquarters Building. Santa Fe. New Mexico: A Historic Structure Report. Division of Conservation, 1985. 7. Toni Carrell. Submerged Cultural Resources Site Report: Noquebav. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1985. 8. Daniel J. Lenihan, Tony Carrell, Thom Holden, C. Patrick Labadie, Larry Murphy, Ken Vrana. Submerged Cultural Resources Study: Isle Royale National Park. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1987. 9. J. Richard Ambler. Archeological Assessment: Navajo National Monument. Division of Anthropology, 1985. 10. John S. Speaker, Joanna Chase, Carol Poplin, Herschel Franks, R. Christopher Goodwin. Archeological Assessment: Barataria Unit. Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. Division of Anthropology, 1986. -

Open to Visitors for Some Time, and Thus Lintel Window Mud Afforded Modest Protection, the Site Remained Vulnerable to Uncon- Wall T-Shaped Trolled Tourism

estled in the canyons and foothills of the Western Sierra Madre lies a suite of caves that harbor some of the richest architectural treasures of the Mesoamerican world. Etched into the landscape by falling rain more than a million years ago, the caves provided refuge for peoples who settled in the region over the millennia, each of whom left an indelible imprint in their deep recesses. The most recent occupants—known to archaeologists as the Paquimé, or “Casas Grandes” people, after a majestic site 120 kilometers to the north where their culture was first identified—began building elaborate earthen dwellings within the ancient grottos nearly 1,000 years ago. Culturally and stylistically linked to the dwellings of the Pueblo peoples of the American Southwest, those of the Paquimé are multistoried adobe structures with stone foundations, wooden support beams, and t-shaped doorways. Many of the structures are composed of a series of small rooms built one atop the other, their exteriors finished in burnished adobe. Pine ladders provided access to upper floors. Some of the rooms were decorated with renderings of animals and anthro- pomorphic figures. NAlthough the structures were erected at some 150 known sites throughout northwestern Mexico, two of the greatest concentrations—Las Cuarenta Casas (40 Houses) and Conjunto by AngelA M.H. ScHuSter Huapoca (Huapoca Complex)—have been found in a series of canyons on the outskirts of Madera in the state of Chihuahua. Over the past decade, both areas have been the focus of a major archae- orMA Arbacci and n B ological campaign aimed at recording what cultural material has survived and elucidating the relation- ship between the people of Paquimé and other cultures of the Mesoamerican world—namely those of Jalisco, Colima, and Nayarit—and the American Southwest. -

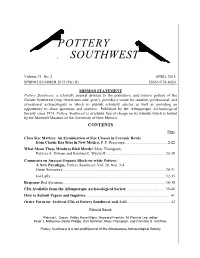

PSW-31-1-2.Pdf

POTTERY SOUTHWEST Volume 31, No. 2 APRIL 2015 SPRING-SUMMER 2015 (Part II) ISSN 0738-8020 MISSION STATEMENT Pottery Southwest, a scholarly journal devoted to the prehistoric and historic pottery of the Greater Southwest (http://www.unm.edu/~psw/), provides a venue for students, professional, and avocational archaeologists in which to publish scholarly articles as well as providing an opportunity to share questions and answers. Published by the Albuquerque Archaeological Society since 1974, Pottery Southwest is available free of charge on its website which is hosted by the Maxwell Museum of the University of New Mexico. CONTENTS Page Class Size Matters: An Examination of Size Classes in Ceramic Bowls from Classic Era Sites in New Mexico, P. F. Przystupa ........................................... 2-22 What Mean These Mimbres Bird Motifs? Marc Thompson, Patricia A. Gilman and Kristina C. Wyckoff ............................................................. 23-29 Comments on Anasazi Organic Black-on-white Pottery: A New Paradigm, Pottery Southwest, Vol. 30, Nos. 3-4 Owen Severence......................................................................................................... 30-31 Joe Lally ..................................................................................................................... 32-35 Response Rod Swenson ........................................................................................................ 36-38 CDs Available from the Albuquerque Archaeological Society ....................................... -

Mexican Macaws: Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains from the Southwest

Mexican Macaws: Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains from the Southwest Item Type Book; text Authors Hargrave, Lyndon L. Publisher University of Arizona Press (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents Download date 30/09/2021 22:04:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/595459 MEXICAN MACAWS Scarlet Macaw. Painting by Barton Wright. ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA NUMBER 20 MEXICAN MACAWS LYNDON L. HARGRAVE Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains From the Southwest THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS TUCSON, ARIZONA 1970 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS Copyright © 1970 The Arizona Board of Regents All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the U.S.A. I. S. B. N.-0-8165-0212-9 L. C. No. 72-125168 PREFACE Any contribution to ornithology and its application to prehistoric problems of avifauna as complex as the present study of macaws, presents many interrelated problems of analysis, visual and graphic presentation, and text form. A great many people have contributed generously of their time, knowledge, and skills toward completion of the present study. I wish here to express my gratitude for this invaluable aid and interest. I am grateful to the National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, and its officials for providing the funds and facilities at the Southwest Archeological Center which have enabled me to carryon this project. In particular I wish to thank Chester A. Thomas, Director of the Center. I am further grateful to the Museum of Northern Arizona and Edward B. Danson, Director, for providing institutional sponsorship for the study as well as making available specimen material and information from their collections and records. -

The End of Casas Grandes

THE END OF CASAS GRANDES Paper presented to the symposium titled The Legacy of Charles C. Di Peso: Fifty Years after the Joint Casas Grandes Project at the 73rd annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology Vancouver, Canada March 27, 2008 Abstract. Charles Di Peso believed that Paquimé, the primary center of the Casas Grandes culture, succumbed to an attack in A.D. 1340. He further argued that the culture survived in the Sierra Madre, where it was encountered by early Spanish military adventurers. Other reviews of the data have come to different conclusions. In this essay I examine and discuss the available chronometric data. This is a revised draft (July 8, 2009). Please check with the author before citing. Corrections and other suggestions for improvement are welcome. David A. Phillips, Jr. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology MSC01 1050, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131-0001 USA [email protected] In 1663 the Spanish founded a settlement and mission near Casas Grandes (Di Peso 1974:3:865, 998). As of that year, beyond question, the Casas Grandes culture no longer existed. Based on tree-ring evidence, in 1338 the culture was thriving. Whatever happened to the culture, it must have happened during the intervening 325 years. The purpose of this essay is to once again guess when the Casas Grandes culture came to and end. Whether we utilize history or archaeology, our starting point for any examination of the problem is the enduring scholarship of Charles Di Peso. Historical Evidence The new colony at Casas Grandes was not an isolated incident. -

Dolan 2016.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE BLACK ROCKS IN THE BORDERLANDS: OBSIDIAN PROCUREMENT IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO AND NORTHWESTERN CHIHUAHUA, MEXICO, A.D. 1000 TO 1450 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SEAN G. DOLAN Norman, Oklahoma 2016 BLACK ROCKS IN THE BORDERLANDS: OBSIDIAN PROCUREMENT IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO AND NORTHWESTERN CHIHUAHUA, MEXICO, A.D. 1000 TO 1450 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Bonnie L. Pitblado, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Patricia A. Gilman ______________________________ Dr. Paul E. Minnis ______________________________ Dr. Samuel Duwe ______________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill ______________________________ Dr. Neil H. Suneson © Copyright by SEAN G. DOLAN 2016 All Rights Reserved. For my parents, Tom and Cathy Dolan Acknowledgments Many people have helped me get to this point. I first thank my professors at Pennsylvania State University where I received my undergraduate education. Dean Snow, Claire McHale-Milner, George Milner, and Heath Anderson introduced me to archaeology, and Alan Walker introduced me to human evolution and paleoanthropology. They encouraged me to continue in anthropology after graduating from Happy Valley. I was fortunate enough to do fieldwork in Koobi Fora, Kenya with professors Jack Harris and Carolyn Dillian, amongst others in 2008. Northern Kenya is a beautiful place and participating in fieldwork there was an amazing experience. Being there gave me research opportunities that I completed for my Master’s thesis at New Mexico State University. Carolyn deserves a special acknowledgement because she taught me about the interesting questions that can be asked with sourcing obsidian artifacts.