ETHJ Vol-30 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled Spreadsheet

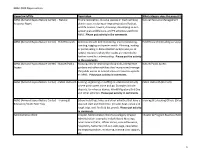

GBAC 2020 Opportunities OpportunityTitle Description What category does the project fall under ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Natural Prairie restoration, invasive species or trash removal, Natural Resource Management Resource Mgmt plant rescue, restoring or improving natural habitat, wildlife houses, towers, chimneys, developing an eco- system plan,wildlife care, and P3 activities specific to ABNC. Please put activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Field Research Activities include bird monitoring, insect monitoring, Field Research (including surveys) banding, tagging and species watch. Planning, leading or participating in data collection and/or analysis of natural resources where the results are intended to further scientific understanding. Please put the activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Nature/Public Mowing, new or improving hiking trails, intrepretive Nature/Public Access Access gardens and other activities that improve and manage the public access to natural areas or resources specific to ABNC. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Public Outreach Leading, organizing or staffing an educational activity Public Outreach (Indirect) where participants come and go. Examples include docents, farm house demos, World Migratory Bird Day and other activities. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Training & School Field trips, hikes and other activities that have a Training & Educating Others (Direct) Education/Youth Field Trips planned start and finish time. Includes boat, canoe and kayak trips, owl, firefly & bat prowls. Please put activity in comments. Administrative Work Chapter Administration WorkSub-category Chapter Chapter & Program Business/Administration Administration: examples include Board Meetings, hours administrator, officer duties, committee work, hospitality, Samaritan roll-out, web page, newsletter, training preparation, mentoring, training class support, etc. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THIRTIETH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1847, TO MARCH 3, 1849 FIRST SESSION—December 6, 1847, to August 14, 1848 SECOND SESSION—December 4, 1848, to March 3, 1849 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE M. DALLAS, of Pennsylvania PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—DAVID R. ATCHISON, 1 of Missouri SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKINS, 2 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—ROBERT BEALE, of Virginia SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—ROBERT C. WINTHROP, 3 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN B. FRENCH, of New Hampshire; THOMAS J. CAMPBELL, 4 of Tennessee SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—NEWTON LANE, of Kentucky; NATHAN SARGENT, 5 of Vermont DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT E. HORNER, of New Jersey ALABAMA CONNECTICUT GEORGIA SENATORS SENATORS SENATORS 14 Arthur P. Bagby, 6 Tuscaloosa Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich Walter T. Colquitt, 18 Columbus Roger S. Baldwin, 15 New Haven 19 William R. King, 7 Selma Herschel V. Johnson, Milledgeville John M. Niles, Hartford Dixon H. Lewis, 8 Lowndesboro John Macpherson Berrien, 20 Savannah REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Fitzgerald, 9 Wetumpka REPRESENTATIVES James Dixon, Hartford Thomas Butler King, Frederica REPRESENTATIVES Samuel D. Hubbard, Middletown John Gayle, Mobile John A. Rockwell, Norwich Alfred Iverson, Columbus Henry W. Hilliard, Montgomery Truman Smith, Litchfield John W. Jones, Griffin Sampson W. Harris, Wetumpka Hugh A. Haralson, Lagrange Samuel W. Inge, Livingston DELAWARE John H. Lumpkin, Rome George S. Houston, Athens SENATORS Howell Cobb, Athens Williamson R. W. Cobb, Bellefonte John M. Clayton, 16 New Castle Alexander H. Stephens, Crawfordville Franklin W. Bowdon, Talladega John Wales, 17 Wilmington Robert Toombs, Washington Presley Spruance, Smyrna ILLINOIS ARKANSAS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE John W. -

The Causes of the Civil War

THE CAUSES OF THE CIVIL WAR: A NEWSPAPER ANALYSIS by DIANNE M. BRAGG WM. DAVID SLOAN, COMMITTEE CHAIR GEORGE RABLE MEG LAMME KARLA K. GOWER CHRIS ROBERTS A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Dianne Marie Bragg 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation examines antebellum newspaper content in an attempt to add to the historical understanding of the causes of the Civil War. Numerous historians have studied the Civil War and its causes, but this study will use only newspapers to examine what they can show about the causes that eventually led the country to war. Newspapers have long chronicled events in American history, and they offer valuable information about the issues and concerns of their communities. This study begins with an overview of the newspaper coverage of the tariff and territorial issues that began to divide the country in the early decades of the 1800s. The study then moves from the Wilmot Proviso in 1846 to Lincoln’s election in 1860, a period in which sectionalism and disunion increasingly appeared on newspaper pages and the lines of disagreement between the North and the South hardened. The primary sources used in this study were a diverse sampling of articles from newspapers around the country and includes representation from both southern and northern newspapers. Studying these antebellum newspapers offers insight into the political, social, and economic concerns of the day, which can give an indication of how the sectional differences in these areas became so divisive. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

A. K. Mcclure and the PEOPLE's PARTY in the CAMPAIGN of 1860

A. K. McCLURE AND THE PEOPLE'S PARTY IN THE CAMPAIGN OF 1860 By WILLIAM H. RUSSELL* pOLITICAL campaigns usually are considered important mainly for the election results that follow. Yet the campaign itself can have lasting effects, both in the discussion of issues and in the relations developed among politicians under stress. This was notably true of the campaign of 1860 in Pennsylvania. This cam- paign was to have strong effects on the future of the Republican Party in Pennsylvania, and on the state's attitude toward the issues leading to the Civil War. It affected the career of nearly every prominent Republican politician, but none more than that of young Alexander K. McClure, state chairman of the party during this critical time. A. K. McClure. by 1860, was already well known as one of the state's shrewdest and most ambitious young politicians. At the age of eighteen he had founded his own newspaper at Mifflintown, and become a spokesman for the anti-slavery Whigs. Six years later he took over the Whig newspaper at Chambersburg, where he achieved financial success and leadership in community affairs. By 1857 he had become a lawyer and won election to the legislature. There he would be a leader of the anti-Democratic forces for several years. With the decline of the Whig Party, he had dallied briefly with the new Know-Nothing movement, then joined in the effort to unite Whigs, Know Nothings, and anti-Nebraska Demo- crats under the Republican label. In 1860, still just thirty-two years of age, he was called to be state chairman of his party. -

Houston a Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need to Be Presentation by Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018

Houston A Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need To Be Presentation By Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018 Harris County Watersheds Population By Watershed Homes Flooded DuringNumber of Harvey Homes By Watershed Flooded in Hurricane Harvey 26,750 30,000 24,730 25,000 20,000 17,090 14,880 15,000 9,450 12,370 11,980 9,120 7,420 3,790 10,000 6,010 2,200 1,890 510 2,720 5,000 310 1,910 230 190 0 490 0 Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. (w/Willow Waterhole) 4% Spring Gulley & Goose Crk. Watershed 4% Greens Bayou Wshed. (w/Halls Bayou) 5% Sims Bayou Wshed. (w/Berry Bayou) 5% San Jacinto River Wshed. (w/Ship Channel) 5% Cedar Bayou Watershed 6% Clear Creek Watershed (w/Turkey Creek) 7% Hunting Bayou Watershed 10% Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. -

Wilmot Proviso

Wilmot Proviso The Wilmot Proviso was introduced on August 8, 1846, in the United States House of Representatives as a rider on a $2 million appropriations bill intended for the final negotiations to resolve the Mexican-American War. The intent of the proviso, submitted by Democratic Congressman David Wilmot, was to prevent the introduction of slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico. The proviso did not pass in this session or in any other session when it was reintroduced over the course of the next several years, but many consider it as the one of first events on the long slide to secession and Civil War which would accelerate through the 1850s. Background Pennsylvania politician David Wilmot After an earlier attempt to acquire Texas by treaty had failed (lithograph by M.H. Traubel). Source: Library to receive the necessary two-thirds approval of the Senate, of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division the United States annexed the Republic of Texas by a joint (Digital ID cph.3c32936). resolution that required simply a majority vote in each house of Congress. President John Tyler signed the bill on March 1, 1845 in the waning days of his presidency. As many expected, the annexation led to war with Mexico. When the war began to wind down, the political focus shifted to what territory, would be acquired from Mexico. Key to this was the determination of the future status of slavery in any new territory. Both major political parties of the time had labored long to keep divisive slavery issues out of national politics. However, the victory of James Polk (Democratic Party) over Henry Clay (Southern Whig) in the 1844 presidential election had caught the Whigs by surprise. -

Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats

CHAPTER SEVEN Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats The plants, predominantly grasses, that flourish in this environment (East Bay Wetlands) serve two biological functions: productivity and protection. From the amount of reduced carbon fixed by these plants during photosynthesis, this ecotone must be considered one of the most productive areas in the world and truly the pantry of the oceans. The dense stand of grass also represents a jungle of roots, stems, and leaves in which the organisms of the marsh, the "peel- ers, " larvae, fry, "bobs," and fingerlings seek refuge from predators. -Frank Fisher, Jr., The Wetlands, Rice University Review, 1972 he Galveston Bay system is composed of a variety of ic systems where the water table is usually at or near the surface, habitat types, ranging from open water areas to wetlands or the land is covered by shallow water (Cowardin et al, 1979). and upland grasslands. These habitats support specific Wetlands in Galveston Bay play several key ecological roles in plant, fish, and wildlife species and contribute to the protecting and maintaining the health and productivity of the estu- T ary. tremendous diversity and overall abundance of bay life. Several specific habitat types have been identified and described in the Galveston Bay system (see FIGURE 2.4). The importance of these The Origin and Importance of Wetlands habitats, their internal functions, and their interconnectedness were Wetlands were formed in Galveston Bay from the long-term presented in Chapter Three as a conceptual model of the bay interaction of the ecosystem's physical processes. These processes ecosystem. The continued productivity and biological diversity of include rainfall and runoff, water table fluctuations, streamflow, the estuarine system is dependent upon the maintenance of varied evapotranspiration, waves and longshore currents, astronomical and abundant high-quality habitat. -

Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 54 Issue 1 Article 7 2016 "Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975 Alex J. Borger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Borger, Alex J. (2016) ""Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 54 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol54/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 54 Spring 2016 Number 1 "Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975 BY ALEX J. BORGER Once a land of tall-grass prairies and an interconnecting system of coastal bayous, the Houston area and the Texas Gulf Coast are now dominated by an extensive sprawl of unchecked residential, commercial, and industrial development. Up against such a formidable human enterprise, wild nature has had little opportunity to thrive. The few natural areas that have managed to survive in the region-usually small patches of quasi-wilderness, nestled between chemical plants, office buildings, shopping centers or subdivisions-are an invaluable resource for recreation and eco-education. Some are also havens for a number of critical flora and fauna that have suffered years of habitat destruction from development or pollution. -

Thesis-Antithesis: Clark & Casey

Thesis-Antithesis: Clark & Casey January 31, 2007 by Dr. G. Terry Madonna and Dr. Michael Young The ghost of Joe Clark has been lurking around the edges of political news lately following the election of Pennsylvania Democrat Bob Casey Jr. to the Senate. Clark served as US Senator from Pennsylvania from 1957 until 1969. Before entering the Senate, he was mayor of Philadelphia, a lawyer, a writer (author of two books), and something of an intellectual (a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences). Clark is remembered due to the historical significance of his last electoral victory; in 1962 he was the last Democrat to be elected to a full six-year term until Bob Casey turned the trick in 2006. Clark and Casey have this history in common. But the two men seem almost polar opposites in most other ways. Tracing the backgrounds, careers, and philosophies of the pair reveal them to be virtual political antonyms--the yin and yang of Pennsylvania politics. Consider: Divergent Family Background--Clark was the quintessential blue blood, coming from a family with roots in the state dating back to the early 19th century. His family hobnobbed with the likes of lawyer/financier Jay Cooke. He attended Harvard as did his dad. He lived a life to the manor born with private country clubs and debutante parties. On the other hand, Casey was the grandson of a coal miner, was reared in a hard scrabble town, and attended Catholic school. One of seven siblings, his early background was solidly middle class, his values solidly middle American, and his politics solidly FDR Democrat. -

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Cover: Top Left Photo Courtesy Armand Bayou Nature Center; All Other Photos © Cliff Meinhardt Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan COVER: TOP LEFT PHOTO COURTESY ARMAND BAYOU NATURE CENTER; ALL OTHER PHOTOS © CLIFF MEINHARDT Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I A Report of the Coastal Coordination Council Pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA170Z1140 Production of this document supported in part by Institutional Grant NA16RG1078 to Texas A&M University from the National Sea Grant Office, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and a grant from ExxonMobil Coporation ii PHOTO © CLIFF MEINHARDT Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................2 The Armand Bayou Watershed Partnership ..................................................................................................................2 State of the Watershed ..............................................................................................................................................2 Institutional Framework ..............................................................................................................................................3 -

Download Download

Hoosiers and the Western Program, 1844-1848 Roger H. Van Bolt* The western program of political action, thoroughly grounded in economic need, was repeatedly rejected by the Polk administration. There had been a traditional support of western interests by both parties for over a decade, but in many respects this support had been one of lip service and of intermittent character. In the period of 1844-1845,however, changes were taking place in the parties themselves and also in government policies, resulting in a growing suspicion in the Northwest that sectional needs were not being met with ade- quate measures to alleviate the stress and strain. Even the parties themselves were becoming distrustful. It is interesting to note that James K. Polk, a political dark horse, had become president because of the failure to resolve the cleavages of the faction.’ Many factors contributed to Indiana’s political action dur- ing this period. The Hoosiers’ interests in the western pro- gram had certain elements in common with their neighbors; yet Indiana possessed no spokesmen for its needs with the en- thusiasm of Jacob Brinkerhoff and Joshua Giddings of Ohio, or John Wentworth of Illinois. Unlike Ohio and Illinois, In- diana’s wool and lead interests were not strong enough to be represented in the national halls. Neither was its lake trade as important as it was to the adjoining states. Michigan City was an enterprising center for the grain growers of northern Indiana, but it was not a Chicago or a Cleveland in importance for Indiana’s trade was not concentrated in the direction of the lake.