Iraq's Minorities on the Verge of Disappearance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraqi Diaspora in Arizona: Identity and Homeland in Women’S Discourse

Iraqi Diaspora in Arizona: Identity and Homeland in Women’s Discourse Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Hattab, Rose Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 20:53:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634364 IRAQI DIASPORA IN ARIZONA: IDENTITY AND HOMELAND IN WOMEN’S DISCOURSE by Rose Hattab ____________________________ Copyright © Rose Hattab 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty oF the SCHOOL OF MIDDLE EASTERN AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial FulFillment oF the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 2 3 DEDICATION This thesis is gratefully dedicated to my grandmothers, the two strongest women I know: Rishqa Khalaf al-Taqi and Zahra Shibeeb al-Rubaye. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Hudson for her expertise, assistance, patience and thought-provoking questions. Without her help, this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the members oF my thesis advisory committee, Dr. Julia Clancy-Smith and Dr. Anne Betteridge, For their guidance and motivation. They helped me turn this project From a series oF ideas and thoughts into a Finished product that I am dearly proud to call my own. My appreciation also extends to each and every Iraqi woman who opened up her heart, and home, to me. -

Arabization and Linguistic Domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine

Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics, 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa Mohand Tilmatine To cite this version: Mohand Tilmatine. Arabization and linguistic domination: Berber and Arabic in the North of Africa. Language Empires in Comparative Perspective, DE GRUYTER, pp.1-16, 2015, Koloniale und Postkoloniale Linguistik / Colonial and Postcolonial Linguistics 978-3-11-040836-2. hal-02182976 HAL Id: hal-02182976 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02182976 Submitted on 14 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. -

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( (

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Abu Ghraib District ( ( ( ( ( ( Idressi Hay Al Askari - ( - 505 Turkey hoor Al basha IQ-P08985 Hamamiyat IQ-P08409 IQ-P08406 Mosul! ! ( ( Erbil ( Syria Iran Margiaba Samadah (( ( ( Baghdad IQ-P08422 ( IQ-P00173 Ramadi! ( ( !\ Al Hay Al Qaryat Askary ( Hadeb Al-Ru'ood Jordan Najaf! IQ-P08381 IQ-P00125 IQ-P00169 ( ( ( ( ( Basrah! ( Arba'at AsSharudi Arabia Kuwait Alef Alf (14000) Albu Khanfar Al Arba' IQ-P08390 IQ-P08398 ( Alaaf ( ( IQ-P00075 ( Al Gray'at ( ( IQ-P08374 ( ( 336 IQ-P08241 Al Sit Alaaf ( (6000) Sabi' Al ( Sabi Al Bur IQ-P08387 Bur (13000) - 12000 ( ( Hasan Sab'at ( IQ-P08438 IQ-P08437 al Laji Alaaf Sabi' Al ( IQ-P00131 IQ-P08435 Bur (5000) ( ( IQ-P08439 ( Hay Al ( ( ( Thaman Alaaf ( Mirad IQ-P08411 Kadhimia District ( as Suki Albu Khalifa اﻟﻛﺎظﻣﯾﺔ Al jdawil IQ-P08424 IQ-P00074 Albu Soda ( Albo Ugla ( (qnatir) ( IQ-P00081 village ( IQ-P00033 Al-Rufa ( IQ-D040 IQ-P00062 IQ-P00105 Anbar Governorate ( ( ( اﻻﻧﺑﺎر Shimran al Muslo ( IQ-G01 Al-Rubaidha IQ-P00174 Dayrat IQ-P00104 ar Rih ( IQ-P00120 Al Rashad Al-Karagul ( Albu Awsaj IQ-P00042 IQ-P00095 IQ-P00065 ( ( ( Albo Awdah Bani Zaid Al-Zuwayiah ( Ad Dulaimiya ( Albu Jasim IQ-P00060 Hay Al Halabsa - IQ-P00117 IQ-P00114 ( IQ-P00022 Falluja District ( ( ( - Karma Uroba Al karma ( Ibraheem ( IQ-P00072 Al-Khaleel اﻟﻔﻠوﺟﺔ Al Husaiwat IQ-P00139 IQ-P00127 ) ( ( Halabsa Al-Shurtan IQ-P00154 IQ-P00031 Karma - Al ( ( ( ( ( ( village IQ-P00110 Ash Shaykh Somod ( ( IQ-D002 IQ-P00277 Hasan as Suhayl ( IQ-P00156 subihat Ibrahim ( IQ-P08189 Muhammad -

Iraq SITREP 2015-5-22

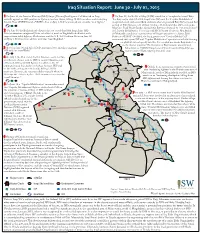

Iraq Situation Report: June 30 - July 01, 2015 1 On June 30, the Interior Ministry (MoI) Suqur [Falcons] Intelligence Cell directed an Iraqi 7 On June 29, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) stated that it “completely cleared” Baiji. airstrike against an ISIS position in Qa’im in western Anbar, killing 20 ISIS members and destroying e Baiji mayor stated that IA, Iraqi Police (IP), and the “Popular Mobilization” Suicide Vests (SVESTs) and a VBIED. Also on July 1, DoD announced one airstrike “near Qa’im.” recaptured south and central Baiji and were advancing toward Baiji Renery and had arrived at Albu Juwari, north of Baiji. On June 30, Federal Police (FP) commander Maj. Gen. Raed Shakir Jawdat claimed that Baiji was liberated by “our armed forces” 2 On June 30, the Baghdadi sub-district director stated that 16th Iraqi Army (IA) and Popular Mobilization Commission (PMC) Deputy Chairman Abu Mahdi Division members recaptured Jubba sub-district, north of Baghdadi sub-district, with al-Muhandis stated that “security forces will begin operations to cleanse Baiji support from tribal ghters, IA Aviation, and the U.S.-led Coalition. Between June 30 Renery of [ISIS].” On July 1, the Iraqi government “Combat Media Cell” and July 1, DoD announced four airstrikes “near Baghdadi.” announced that a joint ISF and “Popular Mobilization” operation retook the housing complex but did not specify whether the complex was inside Baiji district or Dahuk on the district outskirts. e liberation of Baiji remains unconrmed. 3 Between June 30 and July 1 DoD announced two airstrikes targeting Meanwhile an SVBIED targeted an IA tank near the Riyashiyah gas ISIS vehicles “near Walid.” Mosul Dam station south of Baiji, injuring the tank’s crew. -

Basrah Governorate Profile

Basrah Governorate Profile Source map: JAPU Basrah at a Glance Fast Facts Area: 19,070 km2 Capital City: Basrah Average High Temperatures: 17,7°C Average Low Temperatures: 6,8°C (January) to 41,8°C (August) (January) to 27,4°C (July) Population: 2,403,301 Population Distribution Rural-Urban: 20,1%-79,9% Updated December 2015 Geography and Climate Basrah is the most southern governorate of Iraq and borders Iran, Kuwait and Saudi-Arabia. In the south, the governorate is made up of a vast desert plain, intersected by the Shatt Al-Arab waterway which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at Al-Qurnah and empties into the Persian Gulf. Around Al-Qurnah and Al-Medina a number of lakes can be found, while marshland stretches from the north of the governorate into the neighboring governorates of Thi-Qar and Missan. The governorate is Iraq’s only access to the sea. Similar to the surrounding region, the governorate of Basrah has a hot and arid climate. The temperatures in summer are among the highest recorded in the world. Due to the vicinity of the Persian Gulf, humidity and rainfall are however relatively high. The governorate receives an average amount of 152mm of rainfall a year between the months of October and May. Population and Administrative Division The governorate of Basrah is subdivided into seven districts: Abu Al-Khaseeb, Al-Midaina, Al-Qurna, Al- Zubair, Basrah, Fao, and Shatt Al-Arab. The city of Basrah, the governorate’s capital, is Iraq’s third largest urban center. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Turkey and Iraq: the Perils (And Prospects) of Proximity

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT I RAQ AND I TS N EIGHBORS Iraq’s neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the stabilization and reconstruction of “the new Iraq.” As part of the Institute’s “Iraq and Henri J. Barkey Its Neighbors” project, a group of leading specialists on the geopolitics of the region and on the domestic politics of the individual countries is assessing the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq. In addition, these specialists are examining how Turkey and Iraq the situation in Iraq is impacting U.S. bilateral relations with these countries. Henri Barkey’s report on Turkey is the first in a series of USIP special reports on “Iraq The Perils (and Prospects) of Proximity and Its Neighbors” to be published over the next few months. Next in the series will be a study on Iran by Geoffrey Kemp of the Nixon Center. The “Iraq and Its Neighbors” project is directed by Scott Lasensky of the Institute’s Research and Studies Program. For an overview of the topic, see Phebe Marr and Scott Lasensky, “An Opening at Sharm el-Sheikh,” Beirut Daily Star, November 20, 2004. Henri J. Barkey is the Bernard L. and Bertha F. Cohen Professor of international relations at Lehigh University. He served as a member of the U.S. State Department Policy Planning Staff (1998–2000), working primarily on issues related to the Middle East, the eastern Mediterranean, and intelligence matters. -

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi Idps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq May 20191 Contents 1) Access to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KR-I) ................................................................... 2 2) Humanitarian / Socio-Economic Situation in the KR-I ..................................................... 2 a) Shelter ........................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Employment .............................................................................................................................. 4 c) Education ................................................................................................................................... 6 d) Mental Health ............................................................................................................................ 8 e) Humanitarian Assistance ...................................................................................................... 10 3) Returns to Sinjar District........................................................................................................ 10 In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) seized the districts of Sinjar, Tel Afar and the Ninewa Plains, leading to a mass exodus of Yazidis, Christians and other religious communities from these areas. Soon, reports began to surface regarding war crimes and serious human rights violations perpetrated by ISIS and associated armed groups. These included the systematic -

Diyala: 3W Partners Per Health Facility (As of Jan 2018)

IRAQ Diyala: 3W Partners per Health Facility (as of Jan 2018) Kirkuk Consultations by DISTRICT Sulaymaniyah Jan-Dec 2017 Salah al-Din 27,690 25,290 CDO IDPs by district Ba'quba UNICEF Feb 15, 2018 19,374 30,019 WHO WHO Khanaqin 33,442 6,852 Kifri 2,276 1,632 180 Kifri Qoratu Al-Khalis Al-Muqdadiya Baladrooz Ba'quba Khanaqin Kifri Al-Wand 2 Consultations by CAMP CDO Jan-Dec 2017 IOM Al-Wand 1 IDPs by camp Feb 15, 2018 Al-Wand 1 11,374 Khanaqin CDO 715 Al-Wand 2 10,052 Khalis Muskar Saad 26,620 Qoratu 12,016 250 255 Iran 180 Muqdadiya Muskar Saad Diyala Al Wand 2 Al Wand 1 Muskar Saad Qoratu LEGEND IRAQ UIMS IDP Camp Ba'quba Baladrooz Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, 5 or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All reasonable Partners IOM precautions have been taken by WHO to produce this map. The responsibility for its in Diyala interpretation and use lies with the user. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. Baghdad Governorate Wassit Production Date: 07 Mar 2018 Product Name: IRQ_DIYALA_3W_Partners_Per_Health_Facility_07032018 Data source: Health cluster partners Camp into Ba'quba District Ba'quba Camps into Khanaqin Distri Khanaqin Kifri District Diyala Governorate Muskar Saad District Al-Wand 1 Al-Wand 2 Qoratu District Activity UIMS IOM CDO CDO CDO UNICEF -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flas

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News (26 MAR - 01 APR 2020) 79 24 26 13 2 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKES DIYALA GOVERNORATE ISIS 31/MAR/2020 An Armed Group 26/MAR/2020 Injured a Military Forces member in Al-Ba'oda village in Tuz Khurmatu district. Four farmers injured in an armed conflict on the outskirts of the Mandali subdistrict. Iraqi Military Forces 01/APR/2020 ISIS 27/MAR/2020 Launched an airstrike destroying several ISIS hideouts in the Al-Mayta area, between Injured a Popular Mobilization Forces member in a clash in the Naft-Khana area. Diyala and Salah Al-Din border. Security Forces 28/MAR/2020 Found two ISIS hideouts and an IED in the orchards of Shekhi village in the Abi Saida ANBAR GOVERNORATE subdistrict. Popular Mobilization Forces 26/MAR/2020 An Armed Group 28/MAR/2020 Found an ISIS hideout containing fuel tanks used for transportation purposes in the Four missiles hit the Al-Shakhura area in Al-Barra subdistrict, northeast of Baqubah Nasmiya area, between Anbar and Salah Al-Din. district. Security Forces 30/MAR/2020 Popular Mobilization Forces 28/MAR/2020 Found and cleared a cache of explosives inside an ISIS hideout containing 46 homemade Bombarded a group of ISIS insurgents using mortar shells in the Banamel area on the IEDs, 27 gallons of C4, and three missiles in Al-Asriya village in Ramadi district. outskirts of Khanaqin district. ISIS 30/MAR/2020 Popular Mobilization Forces 28/MAR/2020 launched an attack killing a Popular Mobilization Forces member and injured two Security Found and cleared an IED in an agricultural area in the Hamrin lake vicinity, 59km northeast Forces members in Akashat area, west of Anbar. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Correlates Among Iraqi Internally Displaced Persons in Duhok, Iraqi Kurdistan

Posttraumatic stress disorder correlates among Iraqi internally displaced persons in Duhok, Iraqi Kurdistan Perjan Hashim Taha ( [email protected] ) University of Duhok https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3416-6717 Nezar Ismet Taib Duhok Directorate General of Health Hushyar Musa Sulaiman Duhok Directorate General of Health Research article Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, internally displaced persons, Iraq, correlates Posted Date: February 1st, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-179630/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/13 Abstract Background In 2014, the terrorist militant group the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) took over one-third of Iraq. This study measured the rate of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among Iraqi internally displaced persons (IDPs) and examined associated demographic and traumatic risk factors and comorbid psychiatric symptoms. Methods A cross-sectional survey was carried out in April-June 2015 at the Khanke camp, northern Iraq. Trauma exposure and PTSD were measured by the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (Iraqi version), and psychiatric comorbidity was measured by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ- 28). Results Of 822 adult IDPs, 33.8% screened positive for PTSD. Associated factors included exposure to a high number of traumatic events, unmet basic needs and having witnessed the destruction of residential or religious areas. Being a widow was the only linked demographic factor (OR = 14.56, 95% CI: 2.93–72.27). The mean scores of anxiety/insomnia and somatic symptoms were above the average cutoff means (M = 3.74, SD = 1.98, R = 0–7 and M = 3.69, SD = 2.14, R = 0–7, respectively) among the IDPs with PTSD.