The Future of Homelands/Outstations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nhulunbuy Itinerary

nd 2 OECD Meeting of Mining Regions and Cities DarwinDarwin -– Nhulunbuy Nhulunbuy 23 – 24 November 2018 Nhulunbuy Itinerary P a g e | 2 DAY ONE: Friday 23 November 2018 Morning Tour (Approx. 9am – 12pm) 1. Board Room discussions - visions for future, land tenure & other Join Gumatj CEO and other guests for an open discussion surrounding future projects and vision and land tenure. 2. Gulkula Bauxite mining operation A wholly owned subsidiary of Gumatj Corporation Ltd, the Gulkula Mine is located on the Dhupuma Plateau in North East Arnhem Land. The small- scale bauxite operation aims to deliver sustainable economic benefits to the local Yolngu people and provide on the job training to build careers in the mining industry. It is the first Indigenous owned and operated bauxite mine. 3. Gulkula Regional Training Centre & Garma Festival The Gulkula Regional training is adjacent to the mine and provides young Yolngu men and women training across a wide range of industry sectors. These include; extraction (mining), civil construction, building construction, hospitality and administration. This is also where Garma Festival is hosted partnering with Yothu Yindi Foundation. 4. Space Base The Arnhem Space Centre will be Australia’s first commercial spaceport. It will include multiple launch sites using a variety of launch vehicles to provide sub-orbital and orbital access to space for commercial, research and government organisations. 11:30 – 12pm Lunch at Gumatj Knowledge Centre 5. Gumatj Timber mill The Timber mill sources stringy bark eucalyptus trees to make strong timber roof trusses and decking. They also make beautiful furniture, homewares and cultural instruments. -

Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations

H-German Jantzen on Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. Discussion published by Jennifer Wunn on Wednesday, May 26, 2021 Review published on Friday, May 21, 2021 Author: Sean Andrew Wempe Reviewer: Mark Jantzen Jantzen on Wempe, 'Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations' Sean Andrew Wempe. Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. 304 pp. $78.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-090721-1. Reviewed by Mark Jantzen (Bethel College)Published on H-Nationalism (May, 2021) Commissioned by Evan C. Rothera (University of Arkansas - Fort Smith) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56206 Demise or Transmutation for a Unique National Identity? Sean Andrew Wempe’s investigation of the afterlife in the 1920s of the Germans who lived in Germany’s colonies challenges a narrative that sees them primarily as forerunners to Nazi brutality and imperial ambitions. Instead, he follows them down divergent paths that run the gamut from rejecting German citizenship en masse in favor of South African papers in the former German Southwest Africa to embracing the new postwar era’s ostensibly more liberal and humane version of imperialism supervised by the League of Nations to, of course, trying to make their way in or even support Nazi Germany. The resulting well-written, nuanced examination of a unique German national identity, that of colonial Germans, integrates the German colonial experience into Weimar and Nazi history in new and substantive ways. -

Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

arts Article Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA Marie Geissler Faculty of Law Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; [email protected] Received: 19 February 2019; Accepted: 28 April 2019; Published: 20 May 2019 Abstract: This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA. Keywords: Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US. One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. -

An Analysis of Palestinian and Native American Literature

INDIGENOUS CONTINUANCE THROUGH HOMELAND: AN ANALYSIS OF PALESTINIAN AND NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE ________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English ________________________________________ by Alana E. Dakin June 2012 Dakin 2 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of English ____________________ Dr. George Hartley Professor, English Thesis Advisor ____________________ Dr. Carey Snyder Honors Tutorial College, Director of Studies English ____________________ Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College Dakin 3 CHAPTER ONE Land is more than just the ground on which we stand. Land is what provides us with the plants and animals that give us sustenance, the resources to build our shelters, and a place to rest our heads at night. It is the source of the most sublime beauty and the most complete destruction. Land is more than just dirt and rock; it is a part of the cycle of life and death that is at the very core of the cultures and beliefs of human civilizations across the centuries. As human beings began to navigate the surface of the earth thousands of years ago they learned the nuances of the land and the creatures that inhabited it, and they began to relate this knowledge to their fellow man. At the beginning this knowledge may have been transmitted as a simple sound or gesture: a cry of warning or an eager nod of the head. But as time went on, humans began to string together these sounds and bits of knowledge into words, and then into story, and sometimes into song. -

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism Submitted to the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States House of Representatives, and the Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States Senate May 2021 Page 1 of 40 Table of Contents I. Overview of Reporting Requirement ............................................................................................. 2 II. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 III. Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 2 IV. Strategic Intelligence Assessment ................................................................................................... 5 V. Discussion and Comparison of Investigative Activities ................................................................ 9 VI. FBI Data on Domestic Terrorism ................................................................................................. 19 VII. Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 27 Appendix .................................................................................................................................................... -

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: a Short History of National Preparedness Efforts

Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 1 Civil Defense and Homeland Security: A Short History of National Preparedness Efforts September 2006 Homeland Security National Preparedness Task Force 2 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is the result of a requirement by the Director of the Department of Homeland Security’s National Preparedness Task Force to examine the history of national preparedness efforts in the United States. The report provides a concise and accessible historical overview of U.S. national preparedness efforts since World War I, identifying and analyzing key policy efforts, drivers of change, and lessons learned. While the report provides much critical information, it is not meant to be a substitute for more comprehensive historical and analytical treatments. It is hoped that the report will be an informative and useful resource for policymakers, those individuals interested in the history of what is today known as homeland security, and homeland security stakeholders responsible for the development and implementation of effective national preparedness policies and programs. 3 Introduction the Nation’s diverse communities, be carefully planned, capable of quickly providing From the air raid warning and plane spotting pertinent information to the populace about activities of the Office of Civil Defense in the imminent threats, and able to convey risk 1940s, to the Duck and Cover film strips and without creating unnecessary alarm. backyard shelters of the 1950s, to today’s all- hazards preparedness programs led by the The following narrative identifies some of the Department of Homeland Security, Federal key trends, drivers of change, and lessons strategies to enhance the nation’s learned in the history of U.S. -

US Responses to Self-Determination Movements

U.S. RESPONSES TO SELF-DETERMINATION MOVEMENTS Strategies for Nonviolent Outcomes and Alternatives to Secession Report from a Roundtable Held in Conjunction with the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. Department of State Patricia Carley UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE CONTENTS Key Points v Preface viii 1 Introduction 1 2 Self-Determination: Four Case Studies 3 3 Self-Determination, Human Rights, and Good Governance 14 4 A Case for Secession 17 5 Self-Determination at the United Nations 21 6 Nonviolent Alternatives to Secession: U.S. Policy Options 23 7 Conclusion 28 About the Author 29 About the Institute 30 v refugees from Iraq into Turkey heightened world awareness of the Kurdish issue in general and highlighted Kurdish distinctiveness. The forma- tion in the 1970s in Turkey of the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, a radical and violent Marxist-Leninist organization, also intensified the issue; the PKK’s success in rallying the Kurds’ sense of identity cannot be denied. Though the KEY POINTS PKK has retreated from its original demand for in- dependence, the Turks fear that any concession to their Kurdish population will inevitably lead to an end to the Turkish state. - Although the Kashmir issue involves both India’s domestic politics and its relations with neighbor- ing Pakistan, the immediate problem is the insur- rection in Kashmir itself. Kashmir’s inclusion in the state of India carried with it provisions for considerable autonomy, but the Indian govern- ment over the decades has undermined that au- tonomy, a process eventually resulting in - Though the right to self-determination is included anti-Indian violence in Kashmir in the late 1980s. -

Munggurrawuy Yunupingu

Men Hunting with Rifles, c. 1959-62 1993.0004.068 Munggurraway Yunupingu (1907-79) Yolngu language group, Gumatj clan, Yirrkala, Arnhem Land Eucalyptus bark with natural ochres In this eucalyptus bark painting, two men with rifles are depicted hunting wild emus in Arnhem Land in northern Australia. At the top of the piece is a watering hole and an emu eating berries (livistona Australis), known locally as “emu food.” In the background the artist has painted clan patterns of diamonds and crossing lines. Using yellow, red, black, and white ochres, this painting is most likely about Macassans and their influence on Aboriginal culture in Arnhem Land. The main subjects are colored with yellow ochre, while all of the pigments are used for the clan patterns which cover the background. In the height and rise of Aboriginal art in Arnhem Land, Dr. Stuart Scougall and Tony Tuckson commissioned bark paintings from 1959-62 in Yirrkala. The clan designs in this painting are consistent with the Yolngu Gumatj people and the use of eucalyptus bark supports the idea that it is from Yirrkala. It’s likely that this work was purchased by Geoffrey Spence from the mission at Yirrkala at the time of the commissions. It’s unknown whether Spence purchased this work from the artist directly, from the Yirrkala mission, or from Scougall and Tuckson. We do know that Edward Ruhe purchased this work from Geoffrey Spence. Upon examination of this work, it is suspected that the artist is Munggurraway Yunupingu (1907-79) of the Gumatj clan. Born and raised in Yirrkala, Munggurraway was a prominent painter of his time. -

Download My Fact Sheet

Institute for a College of Humanities Sustainable Earth and Social Sciences Christopher Morris, PhD Assistant Professor, Sociology and Anthropology Education PhD, Anthropology, University of Colorado at Boulder Key Interests Environmental Governance | Extractive Economies | Biological and Genetic Resources | Pharmaceutical Politics | Indigeneity | Ethnicity | Property | Colonialism and Postcolonialism | Land Rights | Southern Africa CONTACT Phone: 720-988-8763 | Email: [email protected] Website: https://gmu.academia.edu/ChristopherMorris SELECT PUBLICATIONS Research Focus › Morris, C. (2016). Royal My recent work particularly examines the environmental, indigenous, and spatial politics of pharmaceuticals: contestation over biological resources in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The resources Bioprospecting, rights, and are removed and marketed around the world as medicines by multinational companies. My book traditional authority in South manuscript on this subject highlights the complex relationship between the global governance of Africa. American Ethnologist, biodiversity conservation and commercialization, explosions in indigenous rights consciousness, 43(3), 525–539. and the role of foreign firms in local politics. In another recently completed study, I used › Morris, C. (2019). A interviews with medical doctors and researchers to examine a unique clinical trial in South Africa ‘Homeland’s’ harvest: Biotraffic that assessed the safety and efficacy of an African traditional medicine in HIV-seropositive and biotrade in the persons. contemporary Ciskei region of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 45(3), 597–616. › Morris, C. (2017). Biopolitics and boundary work in South Africa’s sutherlandia clinical trial. Medical Anthropology, 36(7), 685–698. › Morris, C. (2013). Pharmaceutical Bioprospecting and the law: The case of umckaloabo in a former apartheid homeland of South Africa. -

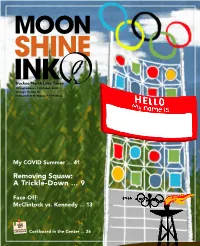

Removing Squaw: a Trickle-Down

Truckee/North Lake Tahoe 10 September – 7 October 2020 Vintage 18, Nip 10 Independent Newspaper • Priceless My COVID Summer ... 41 Removing Squaw: A Trickle-Down ... 9 Face-Off: McClintock vs. Kennedy ... 13 Community Corkboard Corkboard in the Center ... 26 WANT TO EARN STABLE MONTHLY INCOME FROM YOUR VACATION HOME? With the instability in short-term rentals because of COVID-19, have you been thinking about renting longer-term? Our team handles everything needed to find a vetted, locally-employed tenant so you can earn guaranteed monthly income. LandingLocals.com (530)213-3093 CA DRE #02103731 Green Initiatives Over the past fi ve years, we’ve developed a number of initiatives that reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and keep our community clean and blue. New fl ight tracking program (ADS-B) allows for GOING GREEN TO KEEP more e cient fl ying Implementation of Greenhouse Gas Inventory & GHG OUR REGION BLUE. Emission Reduction Plan Land management plan for forest We live in a special place. As a deeply committed community partner, health and wildfi re prevention the Truckee Tahoe Airport District cares about our environment and Open-space land acquisitions for we work diligently to minimize the airport’s impact on the region. From public use new ADS-B technology, to using electric vehicles on the airfi eld, and Electric vehicles & E-bikes used on fi eld preserving more than 1,600 acres of open space land, the District will continue to seek the most sustainable way of operating. Photo by Anders Clark, Disciples of Flight Energy-e cient hangar -

Ilan Pappé Zionism As Colonialism

Ilan Pappé Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa Introduction: The Reputation of Colonialism Ever since historiography was professionalized as a scientific discipline, historians have consid- ered the motives for mass human geographical relocations. In the twentieth century, this quest focused on the colonialist settler projects that moved hundreds of thousands of people from Europe into America, Asia, and Africa in the pre- ceding centuries. The various explanations for this human transit have changed considerably in recent times, and this transformation is the departure point for this essay. The early explanations for human relocations were empiricist and positivist; they assumed that every human action has a concrete explanation best found in the evidence left by those who per- formed the action. The practitioners of social his- tory were particularly interested in the question, and when their field of inquiry was impacted by trends in philosophy and linguistics, their conclusion differed from that of the previous generation. The research on Zionism should be seen in light of these historiographical developments. Until recently, in the Israeli historiography, the South Atlantic Quarterly 107:4, Fall 2008 doi 10.1215/00382876-2008-009 © 2008 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/107/4/611/470173/SAQ107-04-01PappeFpp.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 612 Ilan Pappé dominant explanation for the movement of Jews from Europe to Palestine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was—and, in many ways, still is—positivist and empiricist.1 Researchers analyzed the motives of the first group of settlers who arrived on Palestine’s shores in 1882 according to the testimonies in their diaries and other documents. -

Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025

TEXAS HOMELAND SECURITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2021-2025 LETTER FROM THE GOVERNOR Fellow Texans: Over the past five years, we have experienced a wide range of homeland security threats and hazards, from a global pandemic that threatens Texans’ health and economic well-being to the devastation of Hurricane Harvey and other natural disasters to the tragic mass shootings that claimed innocent lives in Sutherland Springs, Santa Fe, El Paso, and Midland-Odessa. We also recall the multi-site bombing campaign in Austin, the cybersecurity attack on over 20 local agencies, a border security crisis that overwhelmed federal capabilities, actual and threatened violence in our cities, and countless other incidents that tested the capabilities of our first responders and the resilience of our communities. In addition, Texas continues to see significant threats from international cartels, gangs, domestic terrorists, and cyber criminals. In this environment, it is essential that we actively assess and manage risks and work together as a team, with state and local governments, the private sector, and individuals, to enhance our preparedness and protect our communities. The Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025 lays out Texas’ long-term vision to prevent and respond to attacks and disasters. It will serve as a guide in building, sustaining, and employing a wide variety of homeland security capabilities. As we build upon the state’s successes in implementing our homeland security strategy, we must be prepared to make adjustments based on changes in the threat landscape. By fostering a continuous process of learning and improving, we can work together to ensure that Texas is employing the most effective and innovative tactics to keep our communities safe.