13 Arun Gandhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Questions for Gandhi

Discussion Questions for Gandhi Some of the major characters to watch for: Mohandas Gandhi (aka “Mahatma” or “Bapu”), Kasturba Gandhi (his wife), Charlie Andrews (clergyman), Mohammed Jinnah (leader of the Muslim faction), Pandit Nehru (leader of the Hindu faction—also called “Pandi-gi”), Sardar Patel (another Hindu leader), General Jan Smuts, General Reginald Dyer (the British commander who led the Massacre at Amritzar), Mirabehn (Miss Slade), Vince Walker (New York Times reporter) 1. Gandhi was a truly remarkable man and one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century. In fact, no less an intellect than Albert Einstein said about him: “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.” Why him, this small, unassuming man? What qualities caused tens of millions to follow him in his mission to liberate India from the British? 2. Consider Gandhi’s speech (about 30 minutes into the film) to the crowd regarding General Smuts’s new law (fingerprinting Indians, only Christian marriage will be considered valid, police can enter any home without warrant, etc.). The crowd is outraged and cries out for revenge and violence as a response to the British. This is a pivotal moment in Gandhi’s leadership. What does he do to get them to agree to a non-violent response? Why do they follow him? 3. Consider Gandhi’s response to the other injustices depicted in the film (e.g., his burning of the passes in South Africa that symbolize second-class citizenship, his request that the British leave the country after the Massacre at Amritzar, his call for a general strike—a “day of prayer and fasting”—in response to an unjust law, his refusal to pay bail after an unjust arrest, his fasts to compel the Indian people to change, his call to burn and boycott British-made clothing, his decision to produce salt in defiance of the British monopoly on salt manufacturing). -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Kasturba Gandhi an Embodiment of Empowerment

Kasturba Gandhi An Embodiment of Empowerment Siby K. Joseph Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai 2 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong. First Published February 2020 Reprint March 2020 © Author Published by Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai Mani Bhavan, 1st Floor, 19 Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007, MS, India. Website :https://www.gsnmumbai.org Printed at Om Laser Printers, 2324, Hudson Lines Kingsway Camp – 110 009 Siby K. Joseph 3 CONTENTS Foreword Raksha Mehta 5 Preface Siby K. Joseph 7-12 1. Early Life 13-15 2. Kastur- The Wife of Mohandas 16-24 3. In South Africa 25-29 4. Life in Beach Grove Villa 30-35 5. Reunion 36-41 6. Phoenix Settlement 42-52 7. Tolstoy Farm 53-57 8. Invalidation of Indian Marriage 58-64 9. Between Life and Death 65-72 10. Back in India 73-76 11. Champaran 77-80 12. Gandhi on Death’s door 81-85 13. Sarladevi 86-90 14. Aftermath of Non-Cooperation 91-94 15. Borsad Satyagraha and Gandhi’s Operation 95-98 16. Communal Harmony 99-101 4 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. 17. Salt Satyagraha 102-105 18. Second Civil Disobedience Movement 106-108 19. Communal Award and Harijan Uplift 109-114 20. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi. -

Gandhi and Sexuality: in What Ways and to What Extent Was Gandhi’S Life Dominated by His Views on Sex and Sexuality? Priyanka Bose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The South Asianist Journal Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 137 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose [email protected] Though research is coming to light about Gandhi’s views on sexuality, there is still a gap in how this can be related or focused to his broader political philosophy and personal conduct. Joseph Alter states: “It is well known that Gandhi felt that sexuality and desire were intimately connected to social life and politics and that self-control translated directly into power of various kinds both public and private.”* However, I would argue, that the ways in which Gandhi connected these aspects, why and how, have not been fully discussed and are, indeed, not well known. By studying his views and practices with relation to sexuality, I believe that much can be discerned as to how his political philosophy and personal conduct were both established and acted out. In this paper I will aim, therefore, to address: what his views were on sex and sexuality, contextualizing his views with those of the time, what his influences were in his ideology on sex, and how these ideologies framed and related to his political philosophy as well as conduct. -

Annapurna Maharana : a Philanthropist

Odisha Review August - 2013 Annapurna Maharana : A Philanthropist Prabhat Kumar Nanda The girl child born on 3rd November, 1917 in patriotism was fostered in the life of young girl the family of Nabakrushna Choudhury, the Annapurna. She inherited the courage to serve freedom fighter was later became the torch bearer the people from her family members. of social awareness and reformation in the history of Odisha. Annapurna Her father Gopabandhu Choudhury was Maharana popularly known as a Magistrate as appointed by Chuni Appa has left golden the British Government with footprints in the pages of high salary and privileges. The Indian independence clarion call of Mahatma movement. Annapurna was Gandhi insisted Gopabandhu influenced by the philosophy Choudhury to resign from the of Mahatma Gandhi, the job and to join actively in the father of our nation. From the independence movement. childhood she had the Annapurna was highly inspired privilege to be a member of by Pandit Gopabandhu Das Banara Sena, the specific to serve people for their group of children dedicated upliftment. She was themselves for the success of associated with the promotion freedom movement. of Odia Newspaper, ‘The Samaja’, a weekly publication Annapurna had the which was later converted to privilege to come in contact a daily newspaper publication with great leaders like Lok Nayak Jayaprakash to propagate the spirit of patriotism. Narayan, Acharya Vinoba Bhave, Utkalmani Gopabandhu Das, Utkal Gourav Madhusudan Annapurna for the first time was arrested Das and Acharya Harihar. Gopabandhu by the British Government in the year 1930 for Choudhury and Rama Devi were the parents of her association with Salt Movement. -

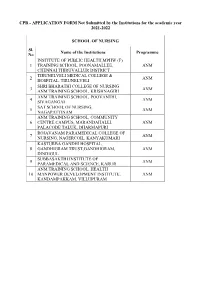

CPR - APPLICATION FORM Not Submitted by the Institutions for the Academic Year 2021-2022

CPR - APPLICATION FORM Not Submitted by the Institutions for the academic year 2021-2022 SCHOOL OF NURSING Sl. Name of the Institutions Programme No INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC HEALTH,MPHW (F) 1 TRAINING SCHOOL, POONAMALLEE, ANM CHENNAI THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TIRUNELVELI MEDICAL COLLEGE & 2 ANM HOSPITAL, TIRUNELVELI SHRI BHARATHI COLLEGE OF NURSING 3 ANM ANM TRAINING SCHOOL, KRISHNAGIRI ANM TRAINING SCHOOL, POOVANTHI, 4 ANM SIVAGANGAI SAT SCHOOL OF NURSING, 5 ANM NAGAPATTINAM ANM TRAINING SCHOOL, COMMUNITY 6 CENTRE CAMPUS, MARANDAHALLI, ANM PALACODE TALUK, DHARMAPURI ROJAVANAM PARAMEDICAL COLLEGE OF 7 ANM NURSING, NAGERCOIL, KANYAKUMARI KASTURBA GANDHI HOSPITAL, 8 GANDHIGRAM TRUST,GANDHIGRAM, ANM DINDIGUL SUBBASAKTHI INSTITUTE OF 9 ANM PARAMEDICAL AND SCIENCE, KARUR ANM TRAINING SCHOOL, HEALTH 10 MANPOWER DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE, ANM KANDAMPAKKAM, VILLUPURAM Sl. Name of the Institutions Programme No REGIONAL TRAINING INSTITUTE OF 11 PUBLIC HEALTH, THIRUVARANKULAM, ANM PUDUKOTTAI SCHOOL OF NURSING, G.B.PANT HOSPITAL, 12 ANM ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS 13 MOTHER THERESA, MAHE ANM ANBARASU INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL AND 14 RESEARCH,TAMBARAM,CHENNAI GNM J.V.INSTITUTE OF NURSING, SCHOOL OF 15 GNM NURSING, CHENNAI SRI KUMARAN SCHOOL OF NURSING, 16 GNM CHENNAI 17 RAGAS SCHOOL OF NURSING, CHENNAI GNM GOVT. STANLEY MEDICAL COLLEGE & 18 GNM HOSPITAL, CHENNAI-600001 TIRUNELVELI MEDICAL COLLEGE & 19 GNM HOSPITAL, TIRUNELVELI GOVT.HEAD QUARTERS HOSPITAL, 20 GNM CUDDALORE 21 S.K.S.HOSPITAL,V.S.EDUCATIONAL TRUST, GNM SALEM-636004 GOVT. MOHAN KUMARAMANGALAM 22 GNM MEDICAL COLLEGE & HOSPITAL,SALEM DR.ALVA PARAMEDICAL EDUCATIONAL 23 GNM INSTITUTE, POLLACHI, COIMBATORE ANNAI THERASA INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL 24 SCIENCES, JAYAKONDAM, ARIYALUR GNM DISTRICT SIVAKUMAR SCHOOL OF NURSING, 25 GNM VELLORE J.P.K.M. -

Kasturba-Gandhi.Pdf

Kasturba Gandhi Aparna Basu Published by: Gandhi National Memorial Society, Agakhan Palace, Pune Kasturba Gandhi Preface This small book on 'Kasturba' owes its origin to the thought that the younger generation of boys and girls should come to know as much as possible the struggles, aspirations and hard work of ordinary simple women who have given shape to present day India. There was an extra ordinary galaxy of such women and their efforts should be recorded which will constitute a unique legacy for the future. Kasturba was one of these women who have left such an imprint on society. Gandhi is known all over the world as an apostle of Peace and Nonviolence and volumes of literature in almost all languages is published and followed on a world-wide scale. But very little is known about his wife Kasturba who played an important role of making Gandhi Eternal. Kasturba was an embodiment of simplicity and compassion. Bapu often used to say that his best workers had passed through kitchen fire under Ba's supervision and passed her test Kasturba took part in every satyagraha campaign and went to jail several times in South Africa and in India. Kasturba died on the evening of 22nd February 1944 at the Agakhan Palace Detention Camp on Bapu's lap and was cremated in the compound of the Detention Camp on 23rd February 1944. Bapu sat watching the funeral pyre till it was all over. Someone had suggested that he should go and rest He replied "This is the final parting, the end of 62 years of shared life. -

Britain, Gandhi and Nehru the Thirty First Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture

Britain, Gandhi and Nehru The Thirty First Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture Gopalkrishna Gandhi Chatham Hall, London November 24, 2010 The first page of Gandhi’s statement written with his left hand (to give the right one rest) at 3 a.m. on October 8, 1931 and read in the Minorities Committee of the Second Round Table Conference, London, the same morning, after a very strenuous night and only half an hour’s sleep Britain, Gandhi and Nehru The Thirty First Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture Gopalkrishna Gandhi Chatham Hall, London November 24, 2010 This lecture is dedicated to the memories of James D.Hunt and Sarvepalli Gopal biographers, respectively, of Gandhi and Nehru Twenty years ago, if a lecture commemorating Nehru and devoted largely to Gandhi had started with a Beatles quote, the audience would have been surprised. And it would not have been amused. Ten years ago a Beatles beginning might not have caused surprise. Today, it will neither surprise nor amuse. We live in jaded times. As I worked on this lecture, my mental disc started playing ‘Ticket to Ride’. John Lennon has said the song demanded a licence to certain women in Hamburg. Paul McCartney said it was about a rail ticket to the town of Ryde. Both, perhaps, were giving us a ticketless ride. Time has its circularities. The song’s line ‘She must think twice, She must do right by me’ seemed to echo the outraged words about another rail ticket, held 1 by Barrister M K Gandhi, when protesting, in 18931, the conductor who ordered him out of his compartment at Maritzburg, South Africa. -

![10-I] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 12, 2014 Maasi 28, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2045](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0429/10-i-chennai-wednesday-march-12-2014-maasi-28-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2045-2340429.webp)

10-I] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 12, 2014 Maasi 28, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2045

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2014 [Price : Rs. 53.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10-I] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 12, 2014 Maasi 28, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2045 Part VI–Section 1 (Supplement) NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. TAMIL NADU NURSES AND MIDWIVES COUNCIL, CHENNAI. (Constituted under Tamil Nadu Act III of 1926) TAMIL NADU MIDWIVES COUNCIL ELECTORAL ROLL THE YEAR 1994 [ 1 ] DTP—VI-1 Sup. (10-I)—1 2 REGISTERED MIDWIVES FOR THE YEAR 1994 Regn.No. Name of the Candidate Particulars Date of Address Regn. 40842 V.C. Fanny Terine Vijayarani The Tamilnadu Dr. MGR 23.02.1994 No.1, Sundar Nagar, Medical University, State bank Officers Chennai trained B.Sc., Colony, Crawford, (Nursing) at Holly Cross Trichy-12. College of Nursing, Trichy from 06.07.88 to 15.04.1992 Exam: May 1992 40843 Vincent Ruby Mercy Govt. of Tamil Nadu 23.02.1994 5/11, R.K. Cert.No:24635 trained a t Venkadasamy St, School of Nursing, Govt. Ponnappa Nadar Nagar, Raja Mirasudhar Hl, Nagercoil-629 004, Thanjavur. From 01.03.92 Kanyakumari Dist. to 31.08.92 Exam: Aug 1992 40844 Muthusamy Ramuthai Govt. of Tamil Nadu 23.02.1994 D/o. Muthusamy, Cert.No:2459 6 trained at Veeralapatty South Coimbatore Medical Garden, Veeralapatty College Hl, Coimbatore. Post, Palani Taluk, From 01.03.92 to 31.08.92 Anna Dist. Exam: Aug 1992 40845 Rajagopal Sheela Govt. of Tamil Nadu 23.02.1994 Matha Koil Street, Cert.No:24176 t rained at No.124, Arugandham Govt. -

Many Gandhis on Our Screens

08 hindustantimes YEARS ON 1869 - 2019 PERSPECTIVE RATNOTTAMA SENGUPTA MANY GANDHIS ON OUR SCREENS n Veteran actor, Rohini Hattangadi, at her residence in Mumbai. AALOK SONI / HT INTERVIEW A young woman n Gandhi film MOVING IMAGE Through the years, filmmakers have been director, Richard inspired by MK Gandhi and the ideas that he espoused as a Attenborough, who played an (left) and leader of the freedom struggle. Each generation has actor, Ben Kingsley, who responded to the Mahatma differently, picking up various played the elements of his vast influence over our collective psyche Mahatma, on aging Kasturba set, 1982. ©COLUMBIA/ Sonal Kalra tough. We were supposed to research our COURTESY EVERETT n [email protected] characters. While Ben found a lot of litera- ALAMY STOCK PHOTO ture on Mahatma Gandhi, I only found two n her tastefully done up apartment in books on Kasturba — Hamari Ba by Van- Mumbai’s Bandra, it is humbling to mala Parikh, and Ba Aur Bapu Ki Sheetal I watch actor Rohini Hattangadi juggle Chhaya Mein by Sushila Nayar. Both between playing host to us and doing books were very personal recollections of ohandas Karamchand Gan- curate film festivals on Gandhi in Delhi (Octo- scourge of untouchability. Pratap, a Brahmin n A still from her own makeup. The 68-year-old is the the authors, and, therefore, limited. dhi. Gandhiji. Mahatma. ber 2018 and January 2019), Kolkata (August- and Kasturi, from a lower caste, are ill-fated Mahatma first Indian actor to win a BAFTA Bapu. One man, so many October 2019), and Singapore (begins Friday lovers in Achhut Kanya (1936), the Bombay Gandhi: 20th (awarded by the British Academy of Film After he read Gandhi’s biography by Louis Fis- lives! and continues till September 30). -

Of Feroze Gandhi and Others out There Rajesh Singh, Visiting Fellow, VIF 11 Oct 2017

Policies & Perspectives VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION The ‘What Ifs’ of Feroze Gandhi and Others Out There Rajesh Singh, Visiting Fellow, VIF 11 Oct 2017 As one reads ‘Feroze the Forgotten Gandhi’, a recently published biography of Jawaharlal Nehru’s son-in-law and Indira Gandhi’s husband, authored by Swedish journalist Bertil Falk, many ‘What Ifs’ come to mind. What if Feroze Gandhi’s marriage had not failed? What if Feroze Gandhi had not been indifferently treated by Nehru and his family? What if he had not been cold-shouldered by his wife? What if he had lived longer and had a chance to realise his full potential? What if he had been around when Lal Bahadur Shastri, with whom he shared a close relationship, became the country’s Prime Minister? The ‘What If’ endeavour is admittedly an academic excursion which is indulged in, at leisurely moments. There is often little purpose behind the exercise but to weigh tantalising possibilities as against irreversible situations. And yet these possibilities offer not just a different roadmap but at times, a preferable one to that adopted as a consequence of circumstances. For instance, the ‘forgotten’ Gandhi would not have been so forgotten if Nehru had groomed him. Feroze Gandhi might even have been Nehru’s right-hand man — the way Indira Gandhi became. Had he lived longer, he may have occupied a ministerial position in Shastri’s Cabinet. And who knows, he could have played a key role in the choice of the next Prime Minister after Shastri’s untimely and sudden death. And even if Indira Gandhi had become Prime Minister, under his sobering influence — he was a democrat and a staunch federalist — she would probably not have imposed the Emergency.