The roles actors perform: role-play and reality in a higher education context

Matthew Riddle, BA

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

Faculty of Arts

University of Melbourne

July, 2006

Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts

(by Advanced Seminar and Shorter Thesis)

Abstract

This thesis undertakes a description and analysis of the way in which Australian higher education students perform roles through the use of online role-play systems at the University of Melbourne. It includes a description of two case studies: DRALE Online, developed in 1997, and The Campaign, developed in 2003. The research undertakes a detailed study of The Campaign, using empirical data derived from classroom observations, online communications, and semi-structured interviews. It undertakes a qualitative analysis of these data using an interpretive approach informed by models drawn from social theory and sociotechnical theory.

Educational authors argue that online educational role-plays engage students in authentic learning, and represent an improvement over didactic teaching strategies. According to this literature, online role-play systems afford students the opportunity of acting and doing instead of only reading and listening. Literature in social theory and social studies of technology takes a different view of certain concepts such as performance, identity and reality. Models such as actor-network theory ask us to consider all actors in the sociotechnical network in order to understand how society and technology are related. This thesis examines these concepts by addressing a series of research questions, such as how students become engaged with identities, how identities are mediated, and the extent to which roles in these role-plays are shaped by the system, the scenario, and the agency of the actors themselves.

An analysis drawing on models from social theory and sociotechnical theory allows an investigation of the interpellation of roles, networks of human and non-human actors, the effect of surveillance on individuals and their self-constitution through performance. The analysis finds that individuals readily take on multiple roles through online role-plays, and that this leads to the development of vocational identities. Some of the constraints on actors are self-imposed or hidden, and indicate inscribed social relationships inside and outside of the online systems. As a result of this analysis, the concept of authentic learning and its relationship to ontology is considered, and future work in this area is suggested.

This is to certify that the thesis comprises only my original work except where indicated in the preface; due acknowledgment has been made in the text to all other material used; the thesis is 20,000-22,000 words in length, inclusive of footnotes, but exclusive of tables, maps, appendices and bibliography.

The Roles Actors Perform

2

Acknowledgements

Research for this thesis was supported by The Research Training Scheme from the Department of Education, Science and Training. The project grew out of discussions with Dr Michael Arnold and Dr Martin Gibbs. I am greatly indebted to them both for their encouragement, support and supervision throughout a project that has been unusually drawn out due to my poor health, but was nevertheless very enjoyable due to their considerable understanding and good humour. I would like to particularly thank Dr David Hirst at The University of Melbourne for his friendship and support in allowing me the time to conduct the empirical research.

Special thanks must go to a number of my long-term mentors in educational technology, including Dr Michael Nott, Dr Jon Pearce, Prof Shirley Alexander, Prof Carmel McNaught, Prof John Hedberg and Dr Michael Keppell. Without your friendship and encouraging words, I would never have completed this work. I would like to thank all the people I have met over the years at The University of Melbourne through whose work I have learnt so much about online role-plays, including Prof Martin Davies, Dr Sally Young, Peter Jones, Myrawin Nelson, Albert Ip, Gordon Yau, Patrick Fong, David Vasjuta, Josella Rye, and all the staff at Educational Technology Services. I am grateful to Dr Mark Poster at UC Irvine for his suggestion to consider the work of Erving Goffman, which had an important impact on the nature of my analysis. I would also like to thank Dr Rosemary Robins and Assoc Prof Helen Verran from the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, who guided me through my coursework.

The final few months of this project were undertaken while working at The

University of Cambridge. I would particularly like to thank John Norman for allowing me the time and flexibility required to complete this project and Dr Lee Wilson and Dr Catherine Howell for their comments and encouragement.

I dedicate this thesis to my dear partner Lotte, my parents, Margaret and Malcolm, and my family and friends for their limitless love and support.

The Roles Actors Perform

3

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ..................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 6 LITERATURE REVIEW................................................................................................... 8

Part 1: Authentic learning and online role-plays...................................................................................8 Part 2: Performance, identity, and reality ........................................................................................... 14

RESEARCH QUESTIONS ...............................................................................................21 METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 22

Primary sources .................................................................................................................................. 22 Analysis............................................................................................................................................... 23 Theoretical approach.......................................................................................................................... 23

CASE STUDIES ............................................................................................................ 25

Case Study 1: DRALE Online............................................................................................................. 25 Case Study 2: The Campaign.............................................................................................................. 30

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ......................................................................................... 34

Getting into the role............................................................................................................................ 34 When the system breaks down ........................................................................................................... 39 Going off the radar.............................................................................................................................. 41 The complexity of relationships ......................................................................................................... 46 Suspending disbelief........................................................................................................................... 48 Freedoms and constraints................................................................................................................... 51 Roles and identities ............................................................................................................................ 54

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY........................................................................................................... 62

The Roles Actors Perform

4

Figures

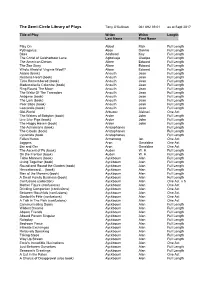

Figure 1: The connections to be simulated by DRALE Online. ........................................................... 26 Figure 2: The DRALE Online design process: a schematic design of the To Do list . . ........................... 28 Figure 3: DRALE Online: A Case File screen with authenticated document....................................... 29 Figure 4: The Campaign Log In Scree n . .............................................................................................. 31 Figure 5: The Campaign To Do List .................................................................................................. 32 Figure 6: Journalist Graham makes intitial contact with Political Adviser Josie.................................... 37 Figure 7: Journalist Graham makes follow up contact with Political Adviser Josie. ............................... 38 Figure 8: Email extract from Adviser student Stacey to Journalist Guido . . ........................................... 43 Figure 9: Email extract from Journalist student Guido to Adviser Stacey............................................. 44 Figure 10: Email extract from Journalist student Guido to Adviser Stacey........................................... 44

Tables

Table 1: Student roles in pairs in The Campaign. ................................................................................ 34 The Roles Actors Perform

5

Introduction

Role-play has long been used as an educational tool to provide learners with a way to understand the real world. Since the advent of the World Wide Web, online role-plays have become widely used in Australian tertiary institutions endeavouring to provide students with authentic learning opportunities (Brown, Collins and Duiguid, 1989). It is argued in the education literature that through the performance of roles, students are able to appreciate a multitude of perspectives on real world scenarios (Herrington and Oliver, 1995). However, work in the area of social studies of technology and sociology asks us to look at the experience of reality and role-play through a different prism. This work raises a number of important issues for the development and use of online role-plays in higher education, including the questions of performance, identity, and reality and their relation to the roles of all of the actors involved in the development and use of role-plays.

This research reported in this thesis undertakes a description and analysis of the way in which tertiary students perform roles through the use of online role-play systems, using the cases of DRALE Online and The Campaign at the University of Melbourne. It interprets and analyses the performance of roles through these systems in a number of dimensions, informed by models drawn from social theory and sociotechnical theory. It therefore does not evaluate the effectiveness of online role-play as a teaching and learning method, but intends to frame an empirical approach informed by social theory and social studies of technology in order to bring new questions and different answers into focus. The empirical work relates specifically to online role-play environments as distinct from traditional role-plays (that is, those which do not involve communication over computer networks). It also draws upon a broader body of work on the use of computer simulations in teaching and learning.

I have arranged this dissertation in a way that is intended to represent as clearly as possible the research process that was undertaken. A Literature Review follows this Introduction, and is separated into two parts. The first focuses on educational research surrounding the design of online role-plays, and the second on social and sociotechnical models used as the frame of reference in this thesis relating to the topics of performance, identity and reality. This is followed by a statement of the particular research questions under investigation in this thesis. The Methodology chapter includes a summary of the methods of

The Roles Actors Perform

6data collection and analysis used, and concludes with a note on the interpretive theoretical approach applied to this analysis.

Then follows a description of two online role-plays that I was involved in developing as case studies that inform this research. The DRALE Online case study offers an example of an online role-play used over eight years with an average of more than 200 undergraduate law students each year. Documents used in the design and development of this exercise are used as a primary source in this research, rather than observations of the system in use, and this case study provides a reference point for some items of discussion that follow. The second case study is on The Campaign, an online role-play developed more recently for small group teaching with postgraduate students in the Media and Communications Programme at the University of Melbourne. Students who participated in The Campaign were observed and interviewed as part of this research, and design documents were analysed. The Results and Discussion Chapter is organised into seven themes that emerged from this analysis in the light of the research questions. This is followed by the Conclusion, which summarises and suggests further work.

The Roles Actors Perform

7

Literature Review

Part 1: Authentic learning and online role-plays

A central argument used to support the use of role-play environments in tertiary learning is that they provide access for students to the world of doing and acting instead of simply receiving instruction through reading and listening. As this literature review will show, the idea that students should participate in their own learning through a form of practice has been mainstream in educational theory for a long time, yet it is still commonplace for tertiary courses to be taught through the heritage method of lectures and seminars. Where methods such as role-play are used, therefore, the argument is that students will be more fully engaged through practice in an authentic learning environment.

Brown, Collins and Duiguid (1989) suggest that the activity and context in which learning takes place are generally regarded as ancillary, distinct, and neutral with respect to what is learned. They argue that this common assumption is clearly incorrect, drawing on Vygotsky’s (1978) theory that knowledge is fundamentally social in nature. Cognitive skills are, they contend, the products of social interactions within an individual’s environment rather than being innate. Learning and acting are therefore not to be thought of as somehow distinct functions. There is a life long process of learning how to act.

Thus Brown, Collins and Duiguid (1989) espouse a situationist approach to learning: individuals learn from the environment within which they find themselves. Learning is situated, and therefore we should focus on providing rich, active learning environments rather than dull and inert classrooms. They cite various studies as evidence, for example one comparing the very limited success of students who learn new words from dictionaries with the fact that they pick up over 5,000 new words a year just through ordinary conversation (Brown, Collins and Duiguid, 1989: 33). Furthermore, learners tend to pick up cultural behaviours and gradually start to act within the norms of that culture through observing and practicing in situ. The problem is that schools use classroom tools such as dictionaries and formulae in a different way from practitioners, so students can do well when assessed but may not be able to use a chosen domain’s conceptual tools in practice.

The activities of a domain are framed by its culture. Their meaning and purpose are socially constructed through negotiations among present and past members. Activities thus cohere in a way that is, in theory, if not always in practice, accessible to members who move within the social framework. These coherent, meaningful, and purposeful activities are authentic,

The Roles Actors Perform

8

according to the definition of the term we use here. Authentic activities then, are most simply defined as the ordinary practices of the culture. (Brown, Collins and Duiguid, 1989: 36)

These authors draw a parallel with the idea of trade apprenticeship as a valuable means of learning and cognition. Cognitive apprenticeship, according to this theory, is an important example of authentic learning. The authors appeal to the accepted understanding that apprenticeship is a valid mode of learning for practical skills in arguing for the learner’s environment to be more like that of a practitioner. In other words, a major problem with teaching students in standard classroom situations is that they may find it difficult to relate to material that is out of context, despite being able to cope with their assessment. They may find it even more difficult when they later attempt to put their knowledge to the test in a working environment.

The development of concepts out of and through continuing authentic activity is the approach of cognitive apprenticeship – a term closely allied to our image of knowledge as a tool. Cognitive apprenticeship supports learning in a domain by enabling students to acquire, develop and use cogitive tools in authentic domain activity. (Brown, Collins and Duiguid, 1989: 46)

Jonassen, Mayes and McAleese (1993) support the view of learning developed by

Brown, Collins and Duiguid (1989) in their ‘Manifesto for a Constructivist Approach to Technology in Higher Education’. Constructivism, an extremely influential model in the educational technology literature, posits that context is all-important for learning.

Too often, learning materials or environments are stripped of contextual relevance. Learners are required to acquire facts and rules that have no direct relevance or meaning to them, because they are not related to anything the learner is interested in or needs to know. We believe that useful knowledge is that which can be transferred to new situations. The most effective learning contexts are those which are problem- or case-based, that immerse the learner in the situation requiring him or her to acquire skills or knowledge in order to solve the problem or manipulate the situation. So, instruction needs to provide contextually-based environments that are meaningful to the learners. (Jonassen, Mayes and McAleese, 1993: 235)

Constructivism refers in this context to the pedagogical approaches based on a theory of experiential learning developed by Piaget (1950) and in particular the more recent variant social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978) which emphasises the importance of social context to the learner. The concept that higher learning can and should provide students with a way to relate to real life experiences is one of the most common arguments for the use of educational technology in general (Jonassen, Mayes and McAleese, 1993) and internet learning environments in particular (Harasim et al, 1995; Teles, 1993; Riel, 1995). Turkle and Papert (1991) refer to what they call epistemological pluralism when talking about

The Roles Actors Perform

9the application of technology to education. The educational constructivist approach they recommend does not attribute special status to ‘logical’ or ‘computational’ approaches over what they term bricolage. Some students, they contend, prefer to appropriate knowledge through more concrete experience, and this is just as valid a form of education. Moreover, forcing students to learn in ways they feel are uncomfortable may actually be detrimental. Turkle (1995: 61) argues that bricoleurs (or ‘tinkerers’) are more likely to find simulations and the internet comfortable because of the way in which connections between concepts can be made through hypertext, and the exploratory style the internet supports.

The apparent incongruity of advocating real life experiences while using online technologies to mediate the learning experience needs to be balanced by the argument that the internet is now a central part of the personal and professional lives of most people who graduate from study at Australian universities (Pattinson & Di Gregorio, 1998). Online experience is real life. It is to be expected that their working lives will involve electronic communication, and in fact ‘information literacy’ is seen as an important life long learning skill. Huang (2002), for example, argues for the application of constructivism in online learning with reference to Vygotsky and Jonassen. The online environment can also facilitate complexities that can be difficult to manage offline. Role-plays often involve multiple documents flowing back and forth in a complex sequence through multiple drafts between a large number of people (Riddle and Davies, 1998).

An idea closely related to cognitive apprenticeship is teleapprenticeship—the concept that networks can mediate student-teacher and student-student discourse, enabling new forms of collaboration using synchronous and asynchronous modes of communication, enhancing knowledge-building strategies and fostering human interactions rather than focussing students’ attention on the technology (Teles 1993, Waugh and Rath 1995). Students can become mentors to their peers, or collaborate in the learning process, either at a distance or locally.