Booklet from the 1998 Festival For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kopcienski, Jacob A., "Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7493. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7493 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Thesis submitted To the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

Muc 4313/5315

MUC 4313/5315 Reading Notes: Chadabe - Electric Sound Sample Exams Moog Patch Sheet Project Critique Form Listening List Truax - Letter To A 25-Year Old Electroacoustic Composer Fall 2003 Table of Contents Chadabe - Electric Sound Chapter Page 1 1 2 3 3 7 4 9 5 10 6 14 7 18 8 21 9 24 10 27 11 29 12 33 Appendex 1 – Terms and Abbreviations 35 Appendex 2 – Backus: Fundamental Physical Quantities 36 Sample Exams Exam Page Quiz 1 37 Quiz 2 40 Mid-Term 43 Quiz 3 47 Quiz 4 50 Final 53 Moog Patch Sheet 59 Project Critique Form 60 Listening List 61 Truax - Letter to a 25-Year Old Electroacoustic Composer 62 i Chapter 1, The Early Instruments What we want is an instrument that will give us a continuous sound at any pitch. The composer and the electrician will have to labor together to get it. (Edgard Varèse, 1922) History of Music Technology 27th cent. B.C. - Chinese scales 6th cent. B.C. - Pythagoras, relationship of pitch intervals to numerical frequency ratios (2:1 = 8ve) 2nd cent. C.E. - Ptolemy, scale-like Ptolemaic sequence 16 cent. C.E. - de Salinas, mean tone temperament 17th cent. C.E. - Schnitger, equal temperament Instruments Archicembalo (Vicentino, 17th cent. C.E.) 31 tones/8ve Clavecin electrique (La Borde, 18th cent. C.E.) keyboard control of static charged carillon clappers Futurist Movement L’Arte dei Rumori (Russolo, 1913), description of futurist mechanical orchestra Intonarumori, boxes with hand cranked “noises” Gran concerto futuristica, orchestra of 18 members, performance group of futurist “noises” Musical Telegraph (Gray, 1874) Singing Arc (Duddell, 1899) Thaddeus Cahill Art of and Apparatus for Generating and Distributing Music Electronically (1897) Telharmonium (1898) New York Cahill Telharmonic Company declared bankruptcy (1914) Electrical Means for Producing Musical Notes (De Forest, 1915), using an audion as oscillator, more cost effective Leon Theremin Aetherphone (1920) a.k.a. -

Interactive Electroacoustics

Interactive Electroacoustics Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jon Robert Drummond B.Mus M.Sc (Hons) June 2007 School of Communication Arts University of Western Sydney Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank my principal supervisor Dr Garth Paine for his direction, support and patience through this journey. I would also like to thank my associate supervisors Ian Stevenson and Sarah Waterson. I would also like to thank Dr Greg Schiemer and Richard Vella for their ongoing counsel and faith. Finally, I would like to thank my family, my beautiful partner Emma Milne and my two beautiful daughters Amelia Milne and Demeter Milne for all their support and encouragement. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. …………………………………………… Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................I LIST OF TABLES..........................................................................................................................VI LIST OF FIGURES AND ILLUSTRATIONS............................................................................ VII ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................................... X CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. -

A Performer's Guide to Multimedia Compositions for Clarinet and Visuals: a Tutorial Focusing on Works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar. Mary Alice Druhan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Druhan, Mary Alice, "A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar." (2003). LSU Major Papers. 36. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/36 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO MULTIMEDIA COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINET AND VISUALS: A TUTORIAL FOCUSING ON WORKS BY JOEL CHADABE, MERRILL ELLIS, WILLIAM O. SMITH, AND REYNOLD WEIDENAAR A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mary Alice Druhan B.M., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.M., University of Cincinnati -

Brief Biography (140 Words) James Paul Sain (B

Very Brief Biography (140 words) James Paul Sain (b. 1959) is Professor of Music at the University of Florida where he teaches electroacoustic and acoustic music composition, theory, and technology. He founded and directed the internationally acclaimed Florida Electroacoustic Music Festival for 17 years. His compositional oeuvre spans all major acoustic ensembles, instrumental and vocal soloists, and embraces electroacoustic music. His works have been featured at major national and international societal events. He has presented his music in concert and given lectures in Asia, Europe, South America and North America. Dr. Sain is President Emeritus of the Society of Composers Inc. He previously served for several terms on American Composers Alliance Board of Governors. His music is available in print from Brazinmusikanta and American Composers Editions and on CD on the Capstone, Electronic Music Foundation, Innova, University of Lanús, Mark Masters, Albany and NACUSA labels. Brief Biography (649 words) James Paul Sain (b. 1959), a native of San Diego, California, is Professor of Music at the University of Florida where he teaches acoustic and electroacoustic music composition as well as music theory. He is Composition, Theory and Technology Co-Chair and the Director of Electroacoustic Music. He founded and directed the internationally acclaimed Florida Electroacoustic Music Festival for 17 years. He is responsible for programming over 1600 works of contemporary art music. Composers-in-residence for the festival included renowned electroacoustic music composers such as Hubert S. Howe, Jr., Cort Lippe, Gary Nelson, Jon Appleton, Joel Chadabe, Larry Austin, Barry Truax, Richard Boulanger, Paul Lansky, James Dashow, Mort Subotnick, John Chowning, Charles Dodge and Annea Lockwood. -

View PDF Document

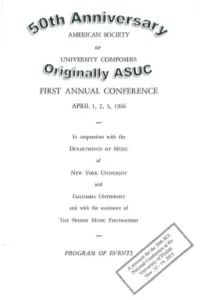

OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS @Lr-ii~~lfillfilUUw L~~~@ i.::: FIRST ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 1, 2, 3, 1966 In cooperation with the DEPARTMENTS OF Music of NEW YORK UNIVERSITY and COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY and with the assistance of THE FROMM Musrc FOUNDATION SEMINARS FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 1966 Loeb Student Center, New York University 566 West Broadway (at Washington Square South) New York City I. The University and the Composing Profession: Prospects and Problems 10:00 AM. Room 510 Chairman: Benjamin Boretz New York University Speakers: Grant Beglarian M ttsic Educators' National Confer.mce Andrew Imbrie University of California, Berkeley Iain Hamilton D11ke University Gharles Wuorinen Columbia University II. Computer Performance of Music 2:30 P.M. Room 510 Chairman: J. K. Randall Princeton University Speakers: Herbert Briin University of Illinois Ercolino Ferretti Massachusetts Institflte of Technology James Tenney Yale University Godfrey Winham Princeton University Panel: Lejaren A. Hiller University of Illinois David Lewin University of California, Berkeley Donald Martino Yale University Harold Shapero Brandeis Universi1y FRIDAY, APRIL 1, 1966 CONCERT-DEMONSTRATIONS I By new-music performance groups resident in American universities 8:30 P.M. McMillin Academic Theatre, Columbia University Broadway at 116 Street New York City NOTE: These programs have been chosen by the participating groups them selves as characteristic representations of their work. The Society has exerted no control over the selections made. I. Octandre (1924)-···-·· --···-·····- ·············-··-··-·· ·Edgard Varese (in memoriam) The Group for Contemporary Music at Columbia University Sophie Sollberger, fl11te Josef Marx, oboe Jack Kreiselman, clarinet Alan Brown, bassoon Barry Benjamin, hom Ronald Anderson, trumpet Philip Jameson, trombone Kenneth Fricker, contrabass Charles Wuorinen, cond11ctor II. -

Fall 2006 Recitative

Authenticity of Utterance Steve Reich’s Works with Voice: An Excerpt By Caroline Mallonée, Ph.D. To set a poem to music is to change it. Steve female-voice Sequenza (1960) and A-Ronne. Each of Reich writes that when, as a student, he first tried these experimental pieces does have a text, and it to set William Carlos Williams’ words to music in is set, however unconventionally; wordless the 1950’s, he “only ‘froze’ its flexible American moments are instances within longer texted vocal speech-derived rhythms.” A decade later, Reich lines. In Reich’s textless vocal writing, the voices turned to the use of recorded speech in Come Out are not soloists, but part of the overall texture of and It’s Gonna Rain, and thereby could use speech the piece. The vocal writing is for the music’s rhythms honestly; in a recording of someone sake, not for the voice’s. speaking, the secondary quality of text setting is avoided. With minimalism’s steady pulse and use of amplifi- cation (there are often parallels drawn between it Reich didn’t use text in his music again until and the rock music of the 1960’s and 70’s) one 1981. However, he did not abandon vocal writing might even argue that Steve Reich’s voices are the in this decade—he included voice parts without equivalent of back-up singers. However, the primary text in several major works composed in the influence that Reich himself names is that of early Recitative 1970’s. His inspiration in such vocal writing is music—Perotin, specifically. -

THE DEPARTMENT of MUSIC STATE UNIVERSITY of NEW YORK at BUFFALO a

THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO a ,-.-.. r -Â¥-^-- presented by L- ._;TMENT OF MUSIC/STATE UNIVERSITV OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO April 7 - April 14, 1984 JAN WILLIAMS. YVAR MIKHASHOFF. LEJAREN HILLER. CO-DIRECTORS BERNADETTE SPEACH. MANAGING DIRECTOR PROGRAM INDEX PAGE concert THE EUROPEAN NEWMUSICSCENE encounter I/- MUSIC OF FRANK ZAPPA concert MUSIC OF FELDMAN AND MARCUS encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: EVOCATIONS concert -1 \ NEW FROM NEW YORK..A.: - encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: INTEGRATIONS concert -' * %5 MUSIC AND THE COMPUTER I a. encounter, concert - -* MUSIC AND THE COMPUTER II encounter, concert AFTER HOURS CABARET: CONTEMPLATIONS concert HILLER-BABBITT COLLAGE - encounter, concert . -^% ." - .' PIANOPERCUSSION EXTRAVAGANZA ,. *< concert Practically from the moment of the founding of the U.B. Music Department by Cameron Baird in 1 953, the creation, performance and study of contemporary music have been integral components of its diverse programs for both students and the public at large. This second North American New Music Festival confirms and reaffirms our commitment to new music here at UB: building on tradi- tion while chronicling today's avant-garde. The task of planning this Festival was made immeasurably easier by the ex~erienceaained from its highly successful antecedents - the Center of the creative and performing ~rtsancfthe ~unein Buffalo Festival. From the residency of Aaron Cooland as the first Slee Professor of Comoosition in 1957, through the 17-year history of the Center - which ended in 1980-the interactionof COG- poser and performer has been our focus; so it is with this new venture as well. -

Dr. Thomas Ciufo

Dr. Thomas Ciufo [email protected] [email protected] / www.ciufo.org Education Ph.D. in Computer Music and New Media Brown University (2004) Ph.D. Dissertation: Computer-Mediated Improvisation Committee members: Todd Winkler (advisor) Wendy Chun and Joel Chadabe (readers) Pauline Oliveros (guest reader / mentor) Masters of Arts in Computer Music and Multimedia Composition Brown University (2002) Masters Thesis: Three Meditations: Discussion of a Recent Work Bachelors of Music in Composition University of Northern Colorado (1988) Selected Professional Appointments Assistant Professor (2017-present) Faculty Innovation Hire, Digital Music and Music Entrepreneurship Music Department, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA Associate Professor (2017) Music Technology and Recording Arts Department of Music, Towson University, Towson, MD Assistant Professor (2011-2017) Music Technology and Recording Arts Department of Music, Towson University, Towson, MD Lecturer (2010-2011) Digital Art / New Media / Sound Art Department of Visual Arts, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA Faculty Advisor (2009-2010) Bachelor of Arts Program in Individualized Studies Goddard College, Plainfield, VT Assistant Professor / Sherman Fairchild Artist-in-Residence (2006-2009) Arts and Technology Smith College, Northampton, MA Postdoctoral Research Associate (2005-2006) Arts, Media, and Engineering Program Herberger College of Fine Arts, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Lecturer / Technical Manager / Researcher (2000-2005) Computer Music and Multimedia Program -

Steim(9014).Pdf

INHOUD CONTENTS Vijfentwintig jaar STEIM, een ouverture, 2 Twenty-five years of STEIM, an overture door Michel Waisvisz b7 Michel Waisvisz Exploded View, het muziekinstrument 5 Exploded View, the Musical Instrument at Twilight, in het schemerlicht, door Nicolas Collins by Nicolas Collins Biografieen artiesten Artist biographies Impossible Music 16 STEIM Achtergracht 19 Jon Rose 1017 WL AMSTERDAM Tel. 020 - 622 86 90 - Fax 626 42 62 Ray Edgar 1 8 1 9 Joel Ryan and Paul Koek Ben Neill en David Wojnarowicz 20 2 1 Sonia Mutsaerts Luc Houtkamp en Robert Dick 22 23 Marie Goyette and Laetitia Sonami The Ex en Tom Corm 24 25 Nicolas Collins Ground Zero 26 27 Michel Waisvisz, Moniek Toebosch, Marie Goyette and John Cameron Installaties Installations Ron Kuivila 28 29 Bob van Baarda Het WEB, Michel Waisvisz 30 Colofon 3 l Colophon vijfentwintig jaar geleden, sterk gemaakt voor een instru- mentale benadering van de elektronische uitvoeringsprak- STEIM VIJFEIVTWIIVTIG JAAR, een ouverture tijk. Dat instrumentale houdt in dat de elektronische muziek Een nieuwe muziektak in ontwikkeling ontmoet op haar pad bliek vaak vanzelfsprekender tot deze inspanning bereid is in STEIM's opvatting pas op het podium haar definitieve heftige opinies, varierend van megalomane toekomstver- dan de beroepsmatige, cultureel overvoede beschouwers vorm moet krijgen; dat de uitvoerende muziekmaker uitein- wachtingen tot regelmatig opduikende doodsverklaringen en beleidsmakers. delijk degene is die via directe en fysieke acties ten over- van het nieuwe genre. Liasons met de duivel worden niet Terugkijkend op de eerste bewegingen in de geschiedenis staan van het publiek de klanken creeert. In feite een meer zo letterlijk aan het nieuwe toegedicht, maar bepalen van de elektronische muziek mogen we vaststellen dat de uiterst traditionele opvatting, maar in de elektronische mu- vaak onbewust nog steeds de toonzetting van de commen- vroege uitingen weliswaar grote klankrijkdom en soms ge- ziek tot dan toe nog weinig vertoond. -

Week 5 1761 - “The Electric Harpsicord” - Instrumental Aspect of Electronic Music

fpa 147 Week 5 1761 - “The Electric Harpsicord” - instrumental aspect of electronic music. Does not always include the more esoteric and philosophical nature of the form - sometimes it’s about new timbres, expediency (like the organ in radio soundtracks, etc.) and other cultural shifts (attention to space in the 60’s). "Galvanic music" 1837 Dr. Page, Salem Mass., purely electrical sound generation: coils close to magnets induce a tone related to the number of turns in the coils "Singing arc" 1899 William Dudel, carbon arc whistles modulated with an electrical coil & capacitor. A keyboard was added later. "Telharmonium" 1906 Thaddeus Cahill, New York Large (several box cars, 200 tons in weight) instrument using large spinning turbines; specifically cogged wheels that induced a frequency related to the number of poles and the speed. Each turbine had an integer multiple of the cogs on it so each harmonic was available for mixing to create the diferent timbres. Since there was no means as yet for electrical amplification, the individual turbines (there was 5 octaves worth driven by a 200 hp motor) were mixed in large iron core transformers. The instrument was controlled by a thirty-six note per octave keyboard which was difcult for one performer to play. The sound was distributed to subscribers over the phone system. "Theremin" 1919 Leo Theremin, Soviet Union A device with two sensors or antenna: One for amplitude and the other for pitch Léon Theremin (born Lev Sergeyevich Termen;Russian: Ле́в Серге́евич Терме́н) (27 August [O.S. 15 August] 1896 – 3 November 1993) was a Russianand Soviet inventor.