Supernatural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Truth About Angels

PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT The Truth About Angels by Donald L. Deffner I grew up during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. My father was a minister. Behind our small home was a dirt alley which led nine blocks to downtown Wichita, Kansas. I can remember when I was a boy the hungry, destitute men who came to the back door begging for food. My mother never turned them down. She shared what little we had, even if only a couple of pieces of bread and a glass of milk. My mother didn’t just say, “Depart in peace! I’ll pray for you! Keep warm and well fed!” (See James 2:16.) No. She acted. She gave. Often I was curious about these mysterious and somewhat scary men. I had a sense that they were “different” than I was, not worse, not better, just different. I always watched these strangers heading back up the alley toward downtown, and sometimes, in a cops-and-robbers fashion, I secretly followed them, jumping behind bushes so I wouldn’t be seen. I think I half expected them to suddenly disappear. After all, my Sunday school teacher, encouraging us to be kind and care for strangers, told us the Bible says that, by doing so, many people have entertained angels without knowing it (see Hebrews 13:2). I never saw any of the men disappear. They were ordinary, hungry human beings. But my Sunday school teacher was right. God does send His angels to us, and they do interact with us—not just to test us and see if we are kind, but to protect us and guide us. -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT M ISSION to Create Innovative Learning Experiences That Equip and Inspire the Next Generation of Creative Problem Solvers

2018 ANNUAL REPORT M ISSION To create innovative learning experiences that equip and inspire the next generation of creative problem solvers. VISION A creative community with a passion for lifelong learning and discovery. V ALUES Playfulness, cooperation, inclusiveness, excellence, respect, innovation, creativity. DEAR FRIENDS, It has been another incredible year for Thinkery. Among almost 455,000 visits to the museum in the 2017-2018 Fiscal Year, Thinkery welcomed visitors from around the world, including more than 7,000 families from other Texas communities, 4,000 families from across the U.S. and 100 families from different countries. We’re thrilled to be Austin’s most-visited cultural institution and a global destination for family fun, learning and discovery. This year we witnessed the growth and expansion of several of our exceptional programs including Community Night Spotlights, EdExchange professional development for teachers, and Thinkery21 program for adults. Our Open Door initiative has grown substantially over the last two years to become a prominent part of ensuring access to our museum and programming. This initiative helps fund free general admission, Community Nights, school field trip discounts, and summer camp scholarships. Please join us in reviewing and celebrating our 2017-18 fiscal year highlights—and affirming our shared mission to create lifelong learners and problem-solvers through innovative, STEAM-based play. Thank you for your continued support and dedication to our mission. Sincerely, Patricia A. Young Brown, CPA Chief Executive Officer The Open Door Initiative provides free admission through OPEN Museums for All and Community Nights, discounted field DOOR trips for Title I schools, and scholarships for camps. -

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1 The most obvious characteristic at the supernatural world of the Kawaiisu is its complexity, which stands in striking contrast to the “simplicity” of the mundane world. Situated on and around the southern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains in south - - central California, the tribe is marginal to both the Great Basin and California culture areas and would probably have been susceptible to the opprobrious nineteenth century term, ‘Diggers’ Yet, if its material culture could be described as “primitive,” ideas about the realm of the unseen were intricate and, in a sense, sophisticated. For the Kawaiisu the invisible domain is tilled with identifiable beings and anonymous non-beings, with people who are half spirits, with mythical giant creatures and great sky images, with “men” and “animals” who are localized in association with natural formations, with dreams, visions, omens, and signs. There is a land of the dead known to have been visited by a few living individuals, and a netherworld which is apparently the abode of the spirits of animals - - at least of some animals animals - - and visited by a man seeking a cure. Depending upon one’s definition, there are apparently four types of shamanism - - and a questionable fifth. In recording this maze of supernatural phenomena over a period of years, one ought not be surprised to find the data both inconsistent and contradictory. By their very nature happenings governed by extraterrestrial fortes cannot be portrayed in clear and precise terms. To those involved, however, the situation presents no problem. Since anything may occur in the unseen world which surrounds us, an attempt at logical explanation is irrelevant. -

Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another

COMICS COSPLAY TV/FILM GAMES SUBMIT CGC Search … Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another Big Splash? Posted by Mark Seifert March 19, 2014 0 Comments Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Tumblr Email Reddit [The Manhattan Projects #18 has been out for a couple weeks, but still — if you haven’t read this issue and plan to, you might want to skip this post for now.] Several years into the digital era for both comics reading and comics production, I still love to look at original comic art up close. The look and feel of the art board, the subtle texture of the ink, the faint traces of changes and corrections… it all adds up to a little extra insight into the time and circumstances behind the comics book’s creation. We’ve mentioned a bunch of noteworthy original art sales here in recent times — from that awe-inspiring Golden Age Action Comics #15 cover by Fred Guardineer, to this Silver Age Fantastic Four #55 page by Jack Kirby, to this Bronze Age classic Amazing Spider- Man #121 cover by John Romita Sr, down to the current record holder for a piece of American comic book art with this Amazing Spider-Man #328 cover by Todd McFarlane. And increasingly, original art sales from much more recent comics are turning heads as well. It’s probably no surprise that Skottie Young original art is highly sought after, or that Walking Dead original art — even panel pages — can command some eye- popping prices. But modern comic art collectors have broadened their interests to many other artists and titles of quality in recent times, such as this Pia Guerra Y: The Last Man panel page that recently went for $1000. -

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas”

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas” Release Date: December 24, 2018 Running Time: 1 hour, 11 minutes Sally: Kay. Fuck, marry, kill. Sam, Dean, Cas. Emily: Ah, fu-- (laugh) Brie: I feel like that’s easy. (laugh) Emily: That’s super easy. Sally: I just -- we gotta start the episode somehow. Emily: OK, kill Sam, obviously. Brie: Duh. Yeah, no, duh. Yeah. Emily: Yeah. Brie: Yeah. Mm. Sally: (laugh) Emily: Uh, then I guess I’d marry Cas? Brie: Yeah … Sally: Fuck Dean? Emily: Yeah. Sally: That’s where I was sitting too. Brie: Yeah. Sally: So we’re all in agreement. Brie: Yeah. Emily: I just -- Cas actually has a personality I can stand. When he actually develops a personality, which is later, I guess, in the series. Sally: Yeah. Brie: I do think, though, that, like, the emotional parts of Dean -- Emily: Yeah. Brie: If that -- if that was, like, turned on all the time. Marry. Emily: My idealized version of Dean -- Brie: Yeah. Emily: I would marry. Brie: Yeah. Yeah. Emily: But the Dean that’s actually on the show? Mm-mm. Fuckin’ leave. Sally: OK! (all laugh) Emily, singing: Have a holly, jolly Christmas … Sally: Um, earlier I was reading an article called -- Brie: Oh! Oh, yeah. Yeah. Emily: Don’t repeat it. It’s the worst. Sally: (laughing) Emily: I know we’re an explicit podcast, but this might be the line of what’s too explicit. Brie: (laugh) Sally: K, it was an article about monster erotica, and the title of the article is also a title for the book. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning Molly Evjen, Andreas Karlsson, Ryan Kelly, Matt Lamb Geography 565 Fall 2010 Abstract As societies change, so too does their relationship with the land. These changing relationships are reflected in and imprinted upon the land on which they live. In order to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has mirrored this changing association with nature through time, we have conducted an environmental history which focuses on four vignettes representing major changes in this relationship. Through research of primary data sources such as historical newsletters, observation, and plat map analysis our research shows that the Arboretum is a palimpsest of landforms and meaning resulting from these changing relationships. Introduction Environmental History is the study of the changing relationship between human beings and the natural world. We believe that the UW arboretum is a landscape that, through time, has been reflective of this changing relationship. Our purpose is to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has changed through time and how these changes reflect a cycle of changing, complex relationships between society and nature. We utilize multiple primary resources in our analysis such as plat maps, CCC newsletters, photographs, observations and personal reflections from our own field journals. We will demonstrate how the UW Arboretum is representative of this changing relationship in a number of ways. It is a reminder of early connections to the land represented by numerous burial mounds. The mounds also symbolize, through the multitude of possible interpretations of their purpose, people’s ever-changing interpretations of our relationship with nature in general. -

Cultural Spectacle: Double Dragon Dance

Cultural Spectacle An unparalleled series of visual spectacles will introduce Richmond, BC, Canada to the world during the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games. Each spectacle will tell the story of Richmond’s local economy, people, heritage and natural environment. Asia’s legendary supernatural creature visits Richmond for Chinese New Year: The long and short of it A spectacular double-dragon dance featuring 150 metre and 75 metre dragons will visit Richmond, BC on Chinese New Year 2010. • The dragon is a symbol of luck in the Chinese • The dragons are 150 metres (492 feet) and 75 culture. metres (246 feet) long. They are predominantly green in colour which symbolizes a great harvest, • Legends have it that the City of Richmond is a or in modern times, abundance. precious pearl in the mouth of the Fraser River and this attracts the dragon. This is why Richmond is • A double dragon dance, rarely seen in Western known as a lucky city to live in. exhibitions, involves two troupes of dancers intertwining the dragons. • A spectacular double dragon dance with two impressively long dragons will visit Richmond and • Part of the dragon myth is the longer the creature, Richmond’s O Zone celebration site on Chinese the more luck it will bring. New Year (Feb. 14, 2010). The Richmond O Zone • Dragons (known as “long” in Chinese) are believed is an official celebration site of the 2010 Olympic to bring good luck to people, which is reflected in Winter Games and runs from February 12 to the their qualities including great power, dignity, 28, 2010. -

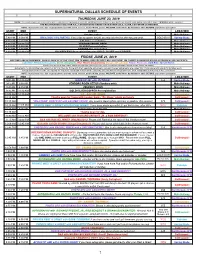

Supernatural Dallas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL DALLAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2019 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please VALIDATE at the Photo Op Validation table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 3:30 PM 7:45 PM Vendors set-up Main Hallway 7:00 PM 9:30 PM BRI & DICK 'S PJ PARTY!!! If you’d like to register tonight, you may join the line after the party ends. SOLD OUT! Spring Glade 7:45 PM 8:30 PM GOLD Pre-registration Main Hallway 7:45 PM 10:00 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Main Hallway 8:30 PM 9:00 PM SILVER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:00 PM 9:30 PM COPPER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:30 PM 10:00 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Main Hallway FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2019 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

Constructing Community and Cosmos: a Bioarchaeological Analysis of Wisconsin Effigy Mound Mortuary Practices and Mound Construction

CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY Anthropology 2012 ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison This dissertation presents an analysis of the mounds, human skeletal remains, grave goods, and ritual paraphernalia interred within mounds traditionally categorized as belonging to the Wisconsin Effigy Mound Tradition. The term ‘Effigy Mound Tradition’ commonly refers to a widespread mound building and ritual phenomenon that spanned the Upper Midwest during the Late Woodland (A.D. 600-A.D. 1150). Specifically, this study explores how features of mound construction and burial may have operated in the social structure of communities participating in this panregional ceremonial movement. The study uses previously excavated skeletal material, published archaeological reports, unpublished field notes, and photographs housed at the Milwaukee Public Museum to examine the social connotations of various mound forms and mortuary ritual among Wisconsin Effigy Mound communities. The archaeological and skeletal datasets consisted of data collected from seven mound sites with an aggregate sample of 197 mounds and a minimum number of individuals of 329. The mortuary analysis in this study explores whether the patterning of human remains interred within mounds were part of a system involved with the 1) creation of collective/ corporate identity, 2) denoting individual distinction and/or social inequality, or 3) a combination of both processes occurring simultaneously within Effigy Mound communities. -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America.