Peter Zumthor in Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Julia Peyton-Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland Dr. Liliana Schönberger Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Light pollution ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 The origins of artificial light ................................................................................ 4 1.1.2 Can light be “pollution”? ...................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Impacts of light pollution on nature and human health .................................... 6 1.1.4 The efforts to minimize light pollution ............................................................... 7 1.2 Hypotheses .................................................................................................................. 8 2 Methods ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Literature review ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Spatial analyses ........................................................................................................ 10 3 Results ....................................................................................................................11 -

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov

Introduction to Modern Literature David Spurr, Fall 2020 11 Nov. Architectural form and representation: Some principles American beginnings of modernism: The Chicago School Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” 1896 https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/architecture/4-205-analysis-of-contemporary- architecture-fall-2009/readings/MIT4_205F09_Sullivan.pdf 18 Nov. Organic architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture,” 1908 https://www.architecturalrecord.com/ext/resources/news/2016/01- Jan/InTheCause/Frank-Lloyd-Wright-In-the-Cause-of-Architecture-March- 1908.pdf “Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect,” Museum of Modern Art, 1940: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2992 Architectural Forum, special issue on Wright, January 1938: https://usmodernist.org/AF/AF-1938-01.pdf 25 Nov. European beginnings of modernism: Walter Gropius Gropius, “Bauhaus Manifesto and Programme,” 1919 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropBau19.p df Gropius, “Principles of Bauhaus Production,” 1926 http://mariabuszek.com/mariabuszek/kcai/ConstrBau/Readings/GropPrdctn.p df Gropius, ”The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus,” 1923, in Herbert Bayer, Bauhaus 1919-1928, Museum of Modern Art: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2735_300190238.pdf De Stijl: Gerrit Rietveld Theo van Doesburg, First De Stijl Manifesto, 1918 https://www.readingdesign.org/de-stijl-manifesto Rietveld, “The New Functionalism in Dutch Architecture,“ 1932 https://modernistarchitecture.wordpress.com/2010/10/20/gerrit-rietveld- %E2%80%9Cnew-functionalism-in-dutch-architecture%E2%80%9D-1932/ Machines for Living: Le Corbusier Le Corbusier, “Five Points Towards a New Architecture,” 1926 https://www.spaceintime.eu/docs/corbusier_five_points_toward_new_archit ecture.pdf Le Corbusier, “Towards a New Architecture,” 1927 https://archive.org/details/TowardsANewArchitectureCorbusierLe/page/n91/ mode/2up E1027: Eileen Gray Joseph Rykwert, “Eileen Gray, Design Pioneer,” 1968. -

The Design of New Buildings in Historical Urban Context: Formal Interpretation As a Way of Transforming Architectural Elements of the Past

THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ELİF BEKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE SEPTEMBER 2018 Approval of the thesis: THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST submitted by ELİF BEKAR in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar _________________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Cânâ Bilsel _________________ Head of Department, Architecture Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Supervisor, Architecture Dept., METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc.Prof. Dr. Haluk Zelef _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Aydan Balamir _________________ Department of Architecture, METU Prof. Dr. Esin Boyacıoğlu _________________ Department of Architecture, Gazi University Date: 07.09.2018 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Elif Bekar Signature : ____________________ iv ABSTRACT THE DESIGN OF NEW BUILDINGS IN HISTORICAL URBAN CONTEXT: FORMAL INTERPRETATION AS A WAY OF TRANSFORMING ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE PAST Bekar, Elif M.Arch., Department of Architecture Supervisor: Prof. -

Interpretation of Minimalism in Architecture According to Various Culture

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 10 Issue 07, July-2021 Interpretation of Minimalism in Architecture According to Various Culture Swetha Elangovan1 , Madhumathi.A2 1 Student, School of Architecture, VIT University, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India 2Professor, School of Architecture, VIT University, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India Abstract:- Minimalism is agreeable as a cultural definition that has an aesthetic approach towards various fields. Since the 1960s, minimalism has been a common movement of art, architecture and lifestyle. Minimalism is a name used to define arts that flourish in content and form with simplicity, as well as a sign of private expressiveness. Minimalism is recognized by reasoning as concept of culture. The modern culture is somehow impregnated by minimalism. Simplicity in architecture allows the user’s/ viewers to experience and grasp the work instantly. Necessary elements in architecture to achieve a simplicity design is limited no. of. materials, play with light, color, and geometric forms and most importantly removing the minor elements to highlight the major elements. The idea of this study is to comprehend how different cultures have diverse understandings towards minimalist architecture. Key words: Minimalist Architecture, Culture, Interpretation, Western, Japanese. 1. INTRODUCTION From 1960s, minimalism has been a common movement of art, architecture and lifestyle. Visual arts and architecture are differentiated and conveyed at one of the points is modernism as a category of art-object (Macarthur, 2002). It is reasonable to say that minimalism is a self-aware version of modernism where it reflects the current way of life. Minimalism concentrated on the most essential elements and a form’s simplicity and it is believed to be evolved from the modern movement whereas few philosophers tend to disagree by indicating that minimalism is indeed very closely linked to a user’s lifestyle and culture. -

PETER ZUMTHOR RECONSIDERS LACMA on VIEW: JUNE 9-SEPTEMBER 15, 2013 LOCATION: Resnick Pavilion

^ Pacific Standard Time PRESENTS: MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN L.A. EXHIBITION: THE PRESENCE OF THE PAST: PETER ZUMTHOR RECONSIDERS LACMA oN VIEW: JUNE 9-SEPTEMBER 15, 2013 LOCATION: resnick pavilion (Los Angeles-January 14, 2013) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA. This exhibition about the proposed future of LACMA’s campus is part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. initiative. The exhibition will be divided into three sections, with the first devoted to an exploration of the museum’s buildings within the complicated history of Hancock Park—a unique site with explicit ties to Los Angeles’s primordial past. For the first time in an exhibition, LACMA will analyze the development of its campus and explain how financial restrictions, political compromises, and unrealized plans have impacted the museum’s architectural aesthetic and art-viewing experience. This section will include rarely seen materials relating to unrealized master plans for LACMA by Renzo Piano and Rem Koolhaas, as well as new insights about the designs by William Pereira, Bruce Goff, and more. Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has been commissioned to rethink the east campus at LACMA by addressing challenges raised by the original structures, and to present a different approach, one that posits a new relationship to the historic site as well as examines the function of an encyclopedic museum in the twenty-first century. The exhibition will display Zumthor’s preliminary ideas about housing LACMA’s permanent collections, including several large models built by the architect’s studio. -

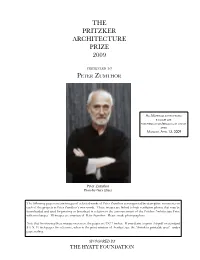

The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2009

THE PRITZKER ARCHITECTURE PRIZE 2009 PRESENTED TO PETER ZUMTHOR ALL MA TERI A LS IN THIS PHOTO BOOKLET A RE FOR PUBLICATION/BRO A DC A ST ON OR A FTER MOND A Y , APRIL 13, 2009 Peter Zumthor Photo by Gary Ebner The following pages contain images of selected works of Peter Zumthor accompanied by descriptive comments on each of the projects in Peter Zumthor’s own words. These images are linked to high resolution photos that may be downloaded and used for printing or broadcast in relation to the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize with no charges. All images are courtesy of Peter Zumthor. Please credit photographers. Note that for viewing these images on screen, the pages are 9X12 inches. If you desire to print this pdf on standard 8½ X 11 inch paper for reference, when in the print window of Acrobat, use the “shrink to printable area” under page scaling. SPONSORED BY THE HYatt FOUNDatION 2007 Brother Klaus Field Chapel Wachendorf, Eifel, Germany (this page and opposite) Photo by Walter Mair sketch by Peter Zumthor The field chapel dedicated to Swiss Saint Nicholas von der Flüe (1417–1487), known as Brother Klaus, was commissioned by farmer Hermann- Josef Scheidtweiler and his wife Trudel and largely constructed by them, with the help of friends, acquaintances and craftsmen on one of their fields above the village. The interior of the chapel room was formed out of 112 tree trunks, which were configured like a tent. In twenty- four working days, layer after layer of concrete, each layer 50 cm thick, was poured and rammed around the tent- like structure. -

The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990S

Redesigning the Physical Boundary: The Emergence of the Glass Age of Museum Architecture from the 1990s 潘 夢斐* Mengfei PAN 1.INTRODUCTION Contemporary museum architecture is buildings’ exalted status. This kind of seeing an age of glass. Both renovation extensive glazing has become an almost projects and new constructions have been indispensable part of the new generation of exploiting glass extensively, as if it is the museum architecture. best solution to serve the spatial functions, By contextualizing the phenomenon of present the architects’ concepts, and address extensive glazing in museum architecture, the institutions’ missions and social this paper aims to discern its connections expectations. Prominent examples include with the museum situation and the the Louvre Pyramid by I. M. Pei (1989) contemporaneity and locality of Japan. It and SANAA’s designs for The 21st Century argues that the increasing exploitation of Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa glass in museum architecture demonstrates (2004) and Louvre-Lens, France (2012). the influence of Neoliberalism on the public This trend of increasing use of glass by institutions and the architects to embrace museum architecture deviates from the visually appealing, technologically demanding, previous model of museums, temples and and commercial elements. It challenges the shrines, with grand staircases and formidable pre-dominant association of glass with look. A new physical boundary of museums, transparency and modernity and argues for a glass walls with their possibility to mediate contextualized reading of glass. Previous visual penetration and similarity with media research in the field of architectural studies interfaces that interact with the surrounding focused on glass employment in all types of and the spectators, is designed in contrast buildings and overlooked the specific with the older type that stresses the situation of museums; while museum studies * Ph. -

Landschaftliche Wandlungen Im Nördlichen Churer Rheintal Werner Nigg

LANDSCHAFTLICHE WANDLUNGEN IM NÖRDLICHEN CHURER RHEINTAL WERNER NIGG Das Rheintal zwischen Reichenau und Sargans bildet in natur- und kulturgeographischer Hinsicht weitgehend eine Einheit. Es ist im folgenden versucht, den neueren Wandlungen im Talabschnitt nördlich von Chur nachzugehen. Natürliche Grundlagen Die rund 20 km lange Talschaft verläuft in süd-nördlicher Richtung und bildet eine breite, tiefe Bresche in der nordbündnerischen Bergwelt. Die Talsohle mit den weit ausladenden Schuttfächern ist im Mittel 3 km breit. Das Rheinbett liegt bei Chur 560, bei Fläsch 500 m ü. M. Die beiden Talhänge sind verschiedenartig. Die Ostflanke besteht zwischen den Einmündungen des Schanfigg und des Prätigau aus der Hochwang-Kette, die Höhen bis 1900 m erreicht und aus weichem penninischen Bündner Schiefer aufgebaut ist. Nördlich der Einmündung des Prätigau, der sogenannten Klus, folgt die Vilan-Falk- nis-Gruppe mit Gipfelhöhen bis 2562 m. Sie wird zur Hauptsache aus weichem Flysch- Schiefer aufgebaut; die schroffe Gipfelpartie des Falknis jedoch aus ostalpinen Kalken. Die westliche Talflanke wird von der Kette Calanda (2706 m) - Pizalun (1478 m) gebildet. Hier sieht man deutlich die dicken helvetischen Kalkschichten ostwärts unter die Talsohle einfallen. Ebenfalls zu den helvetischen Decken gehört der relativ niedrige Fläscherberg, der, isoliert im Tal stehend, die nördliche Begrenzung des Bündner Rheintales markiert. Die petrographischen Verhältnisse sind wesentlich mitverantwortlich an der Ver¬ schiedenartigkeit der beiden Talhänge. Die aus weichen Gesteinen bestehenden östli¬ chen Bergzüge sind durch die Arbeit zahlreicher Rufen (Wildbäche) stark zerfurcht worden und fallen zum Teil steil, fast senkrecht ab. Eine Reihe mächtiger Schuttfächer schiebt sich westwärts ins Tal vor und drängt den Rhein auf die Gegenseite. -

Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions, London, 2000-12

Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS lecture Art Pavilions in Public Parks SERPENTINE GALLERY ART PAVILIONS, LONDON, 2000-12 [email protected] Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) keyword: ART PAVILIONS IN PUBLIC PARKS 1811-17: Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (Sir John Soane) 1897-98: Secession Building, Vienna (Joseph Maria Olbrich) 1908-09: Jakopič Pavilion, Ljubljana (Maks Fabiani) 1895-1995: Bienalle National Pavilions, Venice 2000-12: Serpentine Gallery Pavilions, London 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013: Trimo Urban Crash Competition, Ljubljana Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) http://dulwichgalleryfriends.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/quiz-plan-soane.jpg https://museuminsider.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/dulwich-picture-gallery.jpg London, 1811-17: John Soane: first public art gallery; symmetrical ground floor plan; Dulwich Picture Gallery façade without windows; ground floor plan the sky lights illuminate the paintings indirectly; Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) Latham, I., (1980): Joseph Maria Olbrich. Academy Editions, London: str 25. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Secession_Vienna_June_2006_017.jpg Vienna, 1897-98: Joseph Maria Olbrich: public art gallery for Secession artists; symmetrical ground floor plan; Secession Building pure geometric forms; ground floor plan linear façade ornament; gold and white; Structural Systems Serpentine Gallery Art Pavilions (2000-12) Kos, J., (1993): Umetniški paviljon -

Richtplanung Graubünden – Regionen Landquart, Plessur Und Imboden

Amt für Raumentwicklung Graubünden Uffizi per il svilup dal territori dal chantun Grischun Ufficio per lo sviluppo del territorio dei Grigioni Grabenstrasse 1, 7001 Chur Telefon 081 257 23 23 www.are.gr.ch E-Mail: [email protected] Richtplanung Graubünden – Regionen Landquart, Plessur und Imboden Anpassung im Bereich Windenergieanlagen (Kapitel 7.2.4) Vorranggebiete für Windenergieanlagen im Bündner Rheintal Erläuternder Bericht Stand: Öffentliche Auflage und Vorprüfung Stand 01.03.2018 STW AG für Raumplanung /ARE GR Pf Richtplanung Graubünden – Regionen Landquart, Plessur, Imboden Windenergieanlagen Richtplananpassung Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Das Wichtigste in Kürze 1 2. Ausgangslage 2 2.1 Konzept Windenergie des Bundes 2 2.2 Kantonaler Richtplan und Leitfaden Windenergieanlagen 2 2.3 Regionaler Handlungsbedarf 2 3. Windenergie im Bündner Rheintal 3 3.1 Bestehende WEA 3 3.2 Ausschluss- und Vorbehaltsgebiete (Negativplanung) 3 3.3 Vorranggebiete für Windenergieanlagen (Positivplanung) 4 3.4 Richtplananpassung 4 4. Berührte Interessen und Aspekte 5 4.1 Vorranggebiet WEA Hirschland, Untervaz (Objekt 24.WE.01) 5 4.2 Vorranggebiet WEA Rheinlöser, Zizers (Objekt 24.WE.02) 5 4.3 Vorranggebiet WEA Neugüeter, Maienfeld (Objekt 24.WE.03) 6 4.4 Vorranggebiet WEA Oldis, Haldenstein (Objekt 27.WE.02) 6 4.5 Übersicht der Vorranggebiete 6 5. Grundlagen 9 6. Verfahrenskoordination 9 7. Ergebnisse aus den Verfahren (Auflage, Vernehmlassung und Vorprüfung Bund) 10 7.1 Vorprüfung des kantonalen Richtplans durch den Bund 10 7.2 Öffentliche Auflage 10 7.3 Fazit 10 01.03.2018 Öffentliche Auflage und Vorprüfung Richtplanung Graubünden – Regionen Landquart, Plessur, Imboden Windenergieanlagen Richtplananpassung 1. Das Wichtigste in Kürze Aufgrund der Windverhältnisse im Bündner Rheintal und des technischen Fortschritts im Be- reich Windenergie werden die Regionen in Zukunft vermehrt mit Projektanfragen für Windener- gieanlagen konfrontiert sein. -

Aedes Architecture Forum Berlin Aedes Architecture Forum

Aedes Architecture Forum Berlin Aedes Architecture Forum 3XN architects, 2010 Concept Iñaki Echeverria arquitectos, 2011 More than thirty years ago Kristin Feireiss founded the Aedes Gallery in Berlin. It was the first time that architecture was exhibited and presented as a product of thought processes. Prior to this, the general opinion had been that architecture was merely something to house ex- hibits. The Aedes Gallery introduced the phenomenon of architecture into a specific public domain, bringing urban reality into society in a new way, making it negotiable and political. This new approach to communicate contemporary architecture led to international critical acclaim. Now the Aedes Architecture Forum is one of the world-renowned institutions and cultural brands for built environment, urban planning and associ- ated fields. It has continually stimulated a critical dialogue with the public and has made a signifi- cant contribution to the global discourse regard- ing architecture and urban culture with outstand- ing exhibitions, lectures and conferences. Many significant architects and Pritzker laureates exhibited at Aedes decades before they achieved international fame, including Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Herzog & de Meuron, Kazuyo Sejima, Frank Gehry and Wang Shu. Through its approxi- mately 300 displays, publications, and as many events to date, Aedes has provided a platform for the presentation and analysis of avant-garde con- Reception at Aedes am Pfefferberg, 2010 cepts, visions and built projects. The Aedes Network Campus Berlin (ANCB), a trans- disciplinary metropolitan laboratory, is the ultimate product of this recent development. Horizons of Public Housing, Madrid, 2007 Ai Weiwei, 2008 Zaha Hadid, 2000 Find the Gap, 2005 Yona Friedman, 2004 OMA, 2000 A brief History of Venues In 1980 Aedes started at Savignyplatz in Berlin, moved under the railway viaduct in 1988 and ex- tended 1995 to Hackesche Höfe in the new eastern part of the city. -

Lineages in Switzerland Inferred from Ancient Mitochondrial DNA

diversity Article Millennia-Long Co-Existence of Two Major European Whitefish (Coregonus spp.) Lineages in Switzerland Inferred from Ancient Mitochondrial DNA José David Granado Alonso *, Simone Häberle, Heidemarie Hüster Plogmann, Jörg Schibler and Angela Schlumbaum Department Environmental Science, Integrative Prehistory and Archaeological Science, University of Basel, Spalenring 145, CH 4055 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (H.H.P.); [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-207-42-16 Received: 13 July 2017; Accepted: 20 August 2017; Published: 23 August 2017 Abstract: Archaeological fish remains are an important source for reconstructing past aquatic ecosystems and ancient fishing strategies using aDNA techniques. Here, we focus on archaeological samples of European whitefish (Coregonus spp.) from Switzerland covering different time periods. Coregonus bones and scales are commonly found in archaeological assemblages, but these elements lack species specific features and thus inhibit morphological species identification. Even today, fish taxonomy is confusing and numerous species and ecotypes are recognized, and even more probably existed in the past. By targeting short fragments of the mitochondrial d-loop in 48 morphologically identified Coregonus scales and vertebrae from 10 archaeological sites in Switzerland, endogenous d-loop sequences were found in 24 samples from one Neolithic, two Roman, and four Medieval sites. Two major mtDNA clades, C and N, known from contemporary European whitefish populations were detected, suggesting co-occurrence for at least 5000 years. In the future, NGS technologies may be used to explore Coregonus or other fish species and ecotype diversity in the past to elucidate the human impact on lacustrine/limnic environments.