Virginia Baptists and Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Litany of Remembrance and Thanksgiving

Litany of Remembrance and Thanksgiving Prepared by the Virginia Baptist Historical Society and the Center for Baptist Heritage & Studies for River Road Church, Baptist Richmond, Va. This litany is to serve as a resource for others. It is hosted on the Baptist Joint Committee website with permission. Leader: Our God, our help in ages past, People: Our hope for years to come, Leader: Our shelter from the stormy blast, People: And our eternal home. Leader: From everlasting Thou art God, People: To endless years the same. Voice of an English Baptist: I represent Robert Norden. In God’s providence, my English Baptist brethren sent me and others as “messengers” to our kinsmen who had settled in the Virginia Colony. The year was 1714. We went as “stewards of the mysteries of God” and were found as “trustworthy” in representing the Faith. With courage and conviction, we risked our lives to bring the Gospel to this place. There was Thomas White who died on our long ocean voyage to the Colony. I led in gathering our first church. Other Baptists joined us and started more chuches. People: For all the saints who from their labors rest, Who Thee by faith before the world confessed, Thy name, O Jesus, be forever blest. Voice of Native Americans: Christian settlers came and lived among us and proved by their words and deeds that they cared for us. My people recognized a Supreme Being and sought to understand the mysteries of this God. Baptist ministers shared the good news of Christ in our villages. We established our own churches and joined the English in the work of God’s Kingdom. -

Slavery in Ante-Bellum Southern Industries

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier SLAVERY IN ANTE-BELLUM SOUTHERN INDUSTRIES Series C: Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 1: Mining and Smelting Industries Editorial Adviser Charles B. Dew Associate Editor and Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Slavery in ante-bellum southern industries [microform]. (Black studies research sources.) Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the Duke University Library / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Randolph Boehm—ser. B. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—ser. C. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Martin P. Schipper. 1. Slave labor—Southern States—History—Sources. 2. Southern States—Industries—Histories—Sources. I. Dew, Charles B. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Duke University. Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm). V. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library. Southern Historical Collection. VI. Virginia Historical Society. HD4865 306.3′62′0975 91-33943 ISBN 1-55655-547-4 (ser. C : microfilm) CIP Compilation © 1996 by University Publications -

Baptists in America LIVE Streaming Many Baptists Have Preferred to Be Baptized in “Living Waters” Flowing in a River Or Stream On/ El S

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 126 Baptists in America Did you know? you Did AND CLI FOUNDING SCHOOLS,JOININGTHEAR Baptists “churchingthe MB “se-Baptist” (self-Baptist). “There is good warrant for (self-Baptist). “se-Baptist” manyfession Their shortened but of that Faith,” to described his group as “Christians Baptized on Pro so baptized he himself Smyth and his in followers 1609. dam convinced him baptism, the of need believer’s for established Anglican Mennonites Church). in Amster wanted(“Separatists” be to independent England’s of can became priest, aSeparatist in pastor Holland BaptistEarly founder John Smyth, originally an Angli SELF-SERVE BAPTISM ING TREES M selves,” M Y, - - - followers eventuallyfollowers did join the Mennonite Church. him as aMennonite. They refused, though his some of issue and asked the local Mennonite church baptize to rethought later He baptism the themselves.” put upon two men singly“For are church; no two so may men a manchurching himself,” Smyth wrote his about act. would later later would cated because his of Baptist beliefs. Ironically Brown Dunster had been fired and in his 1654 house confis In fact HarvardLeague Henry president College today. nial schools,which mostof are members the of Ivy Baptists often were barred from attending other colo Baptist oldest college1764—the in the United States. helped graduates found to Its Brown University in still it exists Bristol, England,founded at in today. 1679; The first Baptist college, Bristol Baptist was College, IVY-COVERED WALLSOFSEPARATION LIVE “E discharged -

John Saillant on Unafrican Americans: Nineteenth

Tunde Adeleke. UnAfrican Americans: Nineteenth-Century Black Nationalists and the Civilizing Mission. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1998. xv + 192 pp. $24.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8131-2056-0. Reviewed by John D. Saillant Published on H-SHEAR (February, 1999) Key nineteenth-century American black na‐ laboration with economic and military forces that tionalists--Martin Delany, Alexander Crummell, the black men thought might serve their interests and Henry McNeal Turner--are derisively por‐ but soon proved to be powerful beyond their in‐ trayed in Tunde Adeleke's UnAfrican Americans. fluence. The strength of UnAfrican Americans is Professor Adeleke, educated at the University of its author's frank presentation of the anti-African, Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) and the or civilizationist, face of its subjects. The weak‐ University of Western Ontario and currently em‐ ness of the work is its blindness to the historical ployed at Loyola University (New Orleans), argues background of emigrationism. that Delany, Crummell, and Turner--all occasional Adeleke begins his story around 1850, but emigrationists who themselves sojourned in many of the patterns he analyzes--including the Liberia--were collaborators in the late-nineteenth- roles individuals like Delany, Crummell, and century imperialist ideas and policies that led to Turner played in commerce, governance, and mi‐ the colonization of most of Africa. gration--were established between 1780 and 1830. Adeleke understands his subjects as reaching The black nationalists' beliefs and actions look toward black nationalism, or pan-Africanism, but less individual and more structural, less idealistic failing because of two conditions: First, relatively and more self-serving, if we consider the earlier few African Americans endorsed or envisioned history. -

AMERICAN BAPTISTS a Brief History

AMERICAN BAPTISTS A Brief History ¨ The Origins and Development of Baptist Thought and Practice American Baptists, Southern Baptists and all the scores of other Baptist bodies in the U.S. and around the world grew out of a common tradition begun in the early 17th century. That tradition has emphasized the Lordship and atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ, believers’ baptism, the competency of all believers to be in direct relationship with God and to interpret Scripture, the influence of the Holy Spirit on individual lives and ministries, and the need for autonomous congregations free from government interference or hierarchical polity. The origins of Baptist thought and practice can be seen in the late 16th century in English Congregationalism, which rejected the prevalent “parish” structure of church life (Church of England) where everyone in a given community was a member of a neighborhood parish and where children were baptized. The reaction against that structure was articulated in the concept of “the gathered church,” in which membership was voluntary and based on evidence of conversion, and where baptism (for the most part) was limited to believers. The earliest Baptist churches (1609-1612), although comprised of English- speaking congregants, flourished in Holland, where religious toleration was much greater than in England. Among their leaders were John Smyth, who led the first congregation of 36 men and women, and Thomas Helwys, who returned to England in 1612 to establish the first Baptist church in England. From the beginning Baptists exercised their freedom in choosing to embrace either a strict (predestinarian) Calvinism or Arminianism, which held free will as the fundamental determinant of salvation. -

A Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Writers About Africa

A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CHECKLIST OF AMERICAN NEGRO WRITERS ABOUT AFRICA by Dorothy B. PORTER C3 INCE the latter part of the eighteenth century the American Negro's interest in Africa has beencontinually shown in his writings. Probably the first public statement by an American Negro pertain- ing to Africa was published bv Othello, a Negro resident of Maryland, who in 1 788 protested the stealing of Africans for purposes of enslavement and wrote that ((every corner of the globe would reverberate with the sound of African oppression » if the inhabitants' of Africa had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, seized American citizens, and carried them back to slavery in Africa'. In the following year the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa, appeared. In addition to recollections of childhood, Vassa's book contained interesting descriptions of everyday life in Africa. It is quite possible that Paul CufFee's Brief Account of the Settle- ment and Present Condition o/ the Colony o/ Sierra Leone (1812) gave rise to interest in Sierra Leone as a place for colonization by 1. Carter G. Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations (Washington, D. C. The Associated Publishers, 1925), p. 23. 380 PRLSENCE AFRICAINE' American Negroes. Cuffee, a Negro shipowner and navigator, had explored the area in 1811 for the possibilities of colonization and trade. It seems a meaningful coincidence that in 1817, the very year of Cuffee's death, the American Colonization Society was formed, and for more than fifty years remained a stimulus to published propaganda by American Negroes for and against African colonization . During this period, many American Negroes journeyed to Africa ; but Negro missionaries and bishops of the various church denominations began as early as the 1830's to write of their expe- riences while serving in many parts of Africa, specifically, in Sierra Leone, Liberia, The Belgian Congo, South Africa, and Togoland . -

Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2013 Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race Robert P. Murray University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murray, Robert P., "Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--History. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/23 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Annual Report of the Executive Secretary-Treasurer Rev

Building A Better World Through Christian Missions! 2020-2021 Annual Report of the Executive Secretary-Treasurer Rev. Emmett L. Dunn International Offi ce 8201 Corporate Drive, Suite 1245 Landover, Maryland, USA 20785 Phone: 301.429.3300 Fax: 301.429.3304 Email: [email protected] Web: www.lottcarey.org 2020-2021 Annual Report of the Executive Secretary-Treasurer Rev. Emmett L. Dunn Lott Carey Baptist Foreign Mission Society, Inc. International Office Email: [email protected] 8201 Corporate Drive, Suite 1245 Web: www.lottcarey.org Landover, Maryland, USA 20785 Twitter: @lottcarey Phone: 301.429.3300 Facebook: Lott Carey Fax: 301.429.3304 YouTube: LottCareyTV 124th Lott Carey Annual Session A Virtual Experience Rev. Lott Carey 1780 – 1828 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020-2021 ANNUAL REPORT Convention Officers and Staff......................................................................................... 2 Executive Secretary-Treasurer .........................................................................................3 Rev. Emmett L. Dunn African AIDS Initiative International (AAII), Ethiopia ...................................................7 Elleni Gebreamlak, President Guyana Missionary Baptist Church, Guyana ...................................................................8 Rev. Brenda K. Harewood Lott Carey Baptist Mission, India ..................................................................................13 Mr. Thomas T. Roy Trinity Evangelical Ministry, Jamaica ...........................................................................20 -

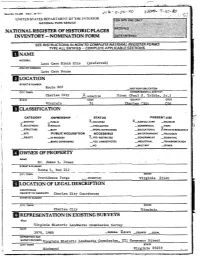

Nomination Form

,. .-: , .~..:... ~ . ,.-&uu,&c.>~*a**-- ,-<, ,-<, -.in-lr..- ForrnNo. lO3OO REV. 19/77) .. , . .. ..., UhITtDSTATES DEPARTMtNTOFlHt INTtKlOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETENATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC ~ottCary Birth- Site (preferred) AND/OR COMMON Lott Cary House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 1 Route 602 -NOT FOR PUBUCATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Charles City -X VICINITY OF First (Paul S. Trible, Jr.) STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 1 Virginia 51 Charles Citv n?f, I CLASSIFICATION t CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE -DISTRICT -PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED XAGRICULNRE -MUSEUM KBUILDINGIS) XPRIVATE -UNOCCUPIED -COMMERCIAL -PARK -STRUCTURE -BOTH -WORK IN PROGRESS -EDUCATIONAL XPRIVATERESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT -RELIGIOUS -OBJECT JN PROCESS LYESRESTRICTED -GOVERNMENT -SCIENTIFIC -BEING CONSIDERED -YES UNRESTRICTED -INDUSTRIAL -TRANSPORTATION -NO _MILITARY -OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY . NAME < ' I.James L. Jones . ,.. ,, STREET& NUMBER Route 1, Box 212 . -- -- - - . CITY. TOWN STATE Providence Forge - VICINITY OF Virginia 23140 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE REG1sTRyOFDEEDs,ETC Charles City Courthouse STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN Charles City Virainia REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS ~LE Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Survey - -- DATE 1979, 1980 -FEDERAL ATE _COUNTY -LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission, 221.- Governor Street CITY.TOWN I "*-. - CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED -UNALTERED XORIG~NALSITE XGOOD -RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE -FAIR -UNEXPOSED --- DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Lott Cary house, Charles City County, has evolved to its present form through a considerable amount of remodeling. Little original fabric remains, although its late 18th- century construction date is evidenced by its plan type and the east elevation chimney. -

Black Territorial Separatism in the South, 1776-1904

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations FOR LAND AND LIBERTY: BLACK TERRITORIAL SEPARATISM IN THE SOUTH, 1776-1904 By Selena Ronshaye Sanderfer Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August 2010 Approved: Professor Richard J. Blackett Professor Dennis C. Dickerson Professor Jane L. Landers Professor Holly J. McCammon Copyright © 2010 by Selena Ronshaye Sanderfer All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation is dedicated to my best friend and family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my dissertation advisor, Richard Blackett, for his support and criticism, without which this endeavor would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, Dennis Dickerson, Jane Landers, and Holly McCammon, for their guidance and advice. I would also like to thank Katie Crawford the Director of Graduate Studies and James Quirin of Fisk University for their insight and valuable commentary. Special thanks to the Marilyn Pilley and Jim Toplin in the Interlibrary Loan Department at the Jean and Alexander Heard Library. Both have gone beyond their duties as librarians to help me locate and gather research materials. I would also like to thank archivists at the Kansas State Historical Society as well as Lynda Silver and Ruth Holmes Whitehead of the Nova Scotia Museum. Not only were they extremely helpful, but their knowledge of primary resources related to black separatism has aided me tremendously in the course of my research. -

The Rhetoric of “Nationhood” in Black American Nationalism

International Journal of Arts and Sciences 3(15): 494- 516 (2010) CD-ROM. ISSN: 1944-6934 © InternationalJournal.org The Rhetoric of “Nationhood” in Black American Nationalism Tunde Adeleke, Iowa State University, USA Abstract: The consciousness and desire for nationhood has been a critical component of Black Nationalism in America from the dawn of enslavement. Reacting to rejection, oppression and the denial of the rights and privileges of American citizenship, leading blacks began to articulate a vision of an independent black nationality. From the mid- nineteenth century emigration movement, through the early twentieth century Garveyist movement to the Civil and post-Civil rights Black Power and Nation of Islam movements, alienated blacks have theorized on the utility of an independent nation and nationality. The construction of this nationality has taken three dimensions: First, internal statism (the envisioning of an independent black nation within the boundaries of the United States); second, external statism (an externally situated and independent black nation); and third, ideological statism (the construction of a “non-state” nation designed for purely psychological consideration). Keywords: Nationalism, Civil Rights, citizenship Introduction Black Nationalism in America is a subject of intense scholarly interest and debates. Generally, scholars have analyzed nationalism within the discourse of alienation. Nationalist ideas and movements have galvanized peoples’ struggles for freedom from domination, exploitation and hegemony. -

George Augustus Stallings Jr

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia George Augustus Stallings Jr. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from George Augustus Stallings, Jr.) Main page See also: George Stallings Contents Featured content George Augustus Stallings Jr. (born March 17, 1948) is the founder of the Current events Imani Temple African-American Catholic Congregation, an African-American- Random article led form of Catholicism. He served as a Roman Catholic priest from 1974 to Donate to Wikipedia 1989. In 1990, he made a public break with the Roman Catholic Church on Wikipedia store The Phil Donahue Show, and was excommunicated that year. Interaction Contents [hide] Help About Wikipedia 1 Early life and priestly ministry Community portal 2 Departure and excommunication from the Catholic Church Recent changes 3 Accusations of sexual misconduct Contact page 4 Relationship with Emmanuel Milingo and Sun Myung Moon 5 Media appearances Tools 6 Published works What links here 7 See also Related changes 8 References Upload file 9 External links Special pages Permanent link Page information Wikidata item Early life and priestly ministry [ edit ] Cite this page Stallings was born in 1948 in New Bern, North Carolina to George Augustus Print/export Stallings, Sr., and Dorothy Smith. His grandmother, Bessie Taylor, introduced him as a boy to worship in a black Baptist church. He enjoyed the service so Create a book Download as PDF much that he said he desired to be a minister. During his high school years Printable version he began expressing "Afrocentric" sentiments, insisting on his right to wear a mustache, despite school rules, as a reflection of black identity.[1] Languages Wishing to serve as a Catholic priest, he attended St.