Capra World Slam Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landrover Supports Anti-Hunters Rolf D Baldus African Indaba Volume 12 Issue 6 - Contents

African Indaba e-Newsletter Volume 12, Number 6 Page 1 Volume 12, Issue No 6 African Indaba eNewsletter December 2014 Landrover Supports Anti-Hunters Rolf D Baldus African Indaba Volume 12 Issue 6 - Contents Landrover Supports Anti-Hunters……………………………………………1 For decades Landrover has been Some Firsts, By The First, For The First.......................................2 an extremely popular vehicle with wildlife Game Industry - Quo Vadis?.......................................................4 conservation agencies, hunters and PH’s CIC Markhor Award: 2008 – 2014……………………………………………5 in Africa. These organizations and people US Fish & Wildlife Service: Lion Not An Endangered Species…10 are therefore an important target group Strategies To Stop Poaching In Selous Game Reserve……………10 for the company. In some countries Elephant Poaching In Northern Mozambique’s Niassa Reserve – Landrover dealers organize special events An Action Replay Of The Selous?..............................................14 for hunters or offer vehicles that are CITES And Confiscated Elephant Ivory And Rhino Horn – To specially equipped for hunting. Destroy Or Not Destroy?..........................................................15 Interesting enough the Landrover Elephant Ivory Trade In China: Trends And Drivers By Yufang Company has selected the "Born Free Gao And Susan B Clark………………………………………………………….17 Foundation", a pronounced British anti- The Complex Policy Issue Of Elephant Ivory Stockpile hunting NGO as its "primary global Management………………………………………………………………………..18 -

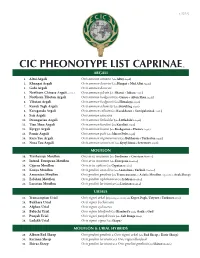

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Low Sequence Diversity of the Prion Protein Gene (PRNP) in Wild Deer and Goat Species from Spain

Pitarch et al. Vet Res (2018) 49:33 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-018-0528-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Low sequence diversity of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in wild deer and goat species from Spain José Luis Pitarch1, Helen Caroline Raksa1, María Cruz Arnal2, Miguel Revilla2, David Martínez2, Daniel Fernández de Luco2, Juan José Badiola1, Wilfred Goldmann3 and Cristina Acín1* Abstract The frst European cases of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in free-ranging reindeer and wild elk were confrmed in Norway in 2016 highlighting the urgent need to understand transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) in the context of European deer species and the many individual populations throughout the European continent. The genetics of the prion protein gene (PRNP) are crucial in determining the relative susceptibility to TSEs. To establish PRNP gene sequence diversity for free-ranging ruminants in the Northeast of Spain, the open reading frame was sequenced in over 350 samples from fve species: Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama), Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica hispanica) and Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra p. pyrenaica). Three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were found in red deer: a silent mutation at codon 136, and amino acid changes T98A and Q226E. Pyrenean chamois revealed a silent SNP at codon 38 and an allele with a single octapeptide-repeat deletion. No polymorphisms were found in roe deer, fallow deer and Iberian wild goat. This appar- ently low variability of the PRNP coding region sequences of four major species in Spain resembles previous fndings for wild mammals, but implies that larger surveys will be necessary to fnd novel, low frequency PRNP gene alleles that may be utilized in CWD risk control. -

The Pyrenean Chamois Johan Espunyes Nozières

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Effects of global change on the diet of a mountain ungulate: the Pyrenean chamois Author Johan Espunyes Nozières Supervisors Emmanuel Serrano Ferron Mathieu Garel Oscar Cabezón Ponsoda Tutor Ignasi Marco Sánchez A dissertation for the degree of doctor philosophiae Departament de Medicina i Cirurgia Animals Facultat de Veterinària Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2019 1 This research was partially funded by the research partnership programme “Approche Intégrée de la Démographie des Populations d’Isard” (Nº2014/08/6171) between the Office de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) and the Servei d’Ecopatologia de la Fauna Salvatge (SEFaS). Johan Espunyes Nozières acknowledges the Government of Andorra for a predoctoral grant, ATC015-AND-2015/2016, 2016/2017 and 2017/2018, a mobility grant AM059- AND-2018 and the award that covered the tuition fees of the third cycle studies AMTC0068-AND/2018. 2 Els doctors Emmanuel Serrano -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76059-1 - Ungulate Management in Europe: Problems and Practices Edited by Rory Putman, Marco Apollonio and Reidar Andersen Index More information Index adaptive management 134–5, 180–2, 377–9 chronic wasting disease 203 Alces alces – see moose climate change Ammotragus lervia – see Barbary sheep effects on ungulate populations 349–66 Axis axis – see axis deer effects on disease and disease transmission 203, axis deer 13, 35, 36 320, 335, 337–40, 360–1 conservation 4, 19, 26, 30, 32, 33, 39–41, 380 Barbary sheep 32, 35, 36 cultural attitudes to hunting 4, 5–9 Bison bonasus – see bison, European bison, European 15, 27–9, 32, 33, 38, 40, 269–70, Dama dama – see fallow deer 275, 301, 353 damage and its management 144–82 blue tongue virus 195, 199, 205, 208, 333, 338–9 damage to agricultural crops 144, 151, 169–71 boar, European wild 15, 81, 89, 91, 92, 93, 94–5, damage to forestry 35, 144, 149–50, 151, 96, 99, 117, 126, 129, 144, 170–1, 175, 200, 171–3 288, 292–4, 300, 301, 303, 322, 327, 334, 335, damage to conservation habitats 13, 35, 37, 43, 336, 355, 365 144, 173–5 bovine tuberculosis 194, 196, 200–1, 208, 322, damage, compensation for 68, 70–1, 169, 171 327, 334 damage, control of 176 brucellosis 197, 202, 208, 327 deer–vehicle collisions – see ungulate–vehicle collisions Capra aegagrus – see goat, European wild disease 192–209, 319–37 Capra ibex – see ibex, alpine disease surveillance 130, 203–4, 328–30 Capra pyrenaica – see ibex, Spanish ungulates as vectors for diseases of livestock or Capreolus -

Temporal Variation in Foraging Activity and Grouping Patterns in a Mountain-Dwelling Herbivore Environmental and Endogenous

Behavioural Processes 167 (2019) 103909 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Behavioural Processes journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/behavproc Temporal variation in foraging activity and grouping patterns in a mountain-dwelling herbivore: Environmental and endogenous drivers T ⁎ Niccolò Fattorinia, , Claudia Brunettia, Carolina Baruzzia, Gianpasquale Chiatanteb, Sandro Lovaria,c, Francesco Ferrettia a Department of Life Sciences, University of Siena. Via P.A. Mattioli 4, 53100 Siena, Italy b Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy c Maremma Natural History Museum, Strada Corsini 5, 58100 Grosseto, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In temperate ecosystems, seasonality influences animal behaviour. Food availability, weather, photoperiod and Seasonality endogenous factors relevant to the biological cycle of individuals have been shown as major drivers of temporal Foraging Activity changes in activity rhythms and group size/structure of herbivorous species. We evaluated how diurnal female Group size foraging activity and grouping patterns of a mountain herbivore, the Apennine chamois Rupicapra pyrenaica Rupicapra ornata, varied during a decreasing gradient of pasture availability along the summer-autumn progression Chamois (July–October), a crucial period for the life cycle of mountain ungulates. Mountain herbivores Females increased diurnal foraging activity, possibly because of constrains elicited by variation in environ- mental factors. Size of mixed groups did not vary, in contrast with the hypothesis that groups should be smaller when pasture availability is lower. Proportion of females in groups increased, possibly suggesting that they concentrated on patchily distributed nutritious forbs. Occurrence of yearlings in groups decreased, which may have depended on dispersal of chamois in this age class. -

Diversity and Evolution of the Mhc-DRB1 Gene in the Two Endemic Iberian Subspecies of Pyrenean Chamois, Rupicapra Pyrenaica

Heredity (2007) 99, 406–413 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diversity and evolution of the Mhc-DRB1 gene in the two endemic Iberian subspecies of Pyrenean chamois, Rupicapra pyrenaica J Alvarez-Busto1, K Garcı´a-Etxebarria1, J Herrero2,3, I Garin4 and BM Jugo1 1Genetika, Antropologia Fisikoa eta Animali Fisiologia Saila, Zientzia eta Teknologia Fakultatea, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain; 2Departamento de Ecologı´a, Universidad de Alcala´ de Henares, Alcala´ de Henares, Spain; 3EGA Wildlife Consultants, Zaragoza, Spain and 4Zoologı´a eta Animali Zelulen Biologia Saila, Zientzia eta Teknologia Fakultatea, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain Major histocompatibility complex class II locus DRB variation recent parasitic infections by sarcoptic mange. A phyloge- was investigated by single-strand conformation polymorph- netic analysis of both Pyrenean chamois and DRB alleles ism analysis and sequence analysis in the two subspecies of from 10 different caprinid species revealed that the chamois Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) endemic to the alleles form two monophyletic groups. In comparison with Iberian Peninsula. Low levels of genetic variation were other Caprinae DRB sequences, the Rupicapra alleles detected in both subspecies, with seven different alleles in R. displayed a species-specific clustering that reflects a large p. pyrenaica and only three in the R. p. parva. After applying temporal divergence of the chamois from other caprinids, as the rarefaction method to cope with the differences in sample well as a possible difference in the selective environment for size, the low allele number of parva was highlighted. -

Revisiting Biogeography of Livestock Animal Domestication

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/786442; this version posted October 1, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Revisiting biogeography of livestock animal domestication Indrė Žliobaitė University of Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Written: December, 2017 Last revised: September, 2019 Abstract Human society relies on four main livestock animals – sheep, goat, pig and cattle, which all were domesticated at nearly the same time and place. Many arguments have been put forward to explain why these animals, place and time were suitable for domestication, but the question – why only these, but not other animals, still does not have a clear answer. Here we offer a biogeographical perspective: we survey global occurrence of large mammalian herbivore genera around 15 000 – 5 000 years before present and compile a dataset characterising their ecology, habitats and dental traits. Using predictive modelling we extract patterns from this data to highlight ecological differences between domesticated and non- domesticated genera. The most suitable for domestication appear to be generalists adapted to persistence in marginal environments of low productivity, largely corresponding to cold semi-arid climate zones. Our biogeographic analysis shows that even though domestication rates varied across continents, potentially suitable candidate animals were rather uniformly distributed across continents. We interpret this pattern as a result of an interface between cold semi-arid and hot semi-arid climatic zones. We argue that hot Semi-arid climate was most suitable for plant domestication, cold Semi-arid climate selected for animals most suitable for domestication as livestock. -

Feral Goats and Sheep Steven C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Publications Health Inspection Service 2018 Feral Goats and Sheep Steven C. Hess USGS Pacific sI land Ecosystems Research Center Dirk H. Van Vuren University of California, Davis Gary W. Witmer USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Hess, Steven C.; Van Vuren, Dirk H.; and Witmer, Gary W., "Feral Goats and Sheep" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2029. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2029 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Government Publication Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services 14 Feral Goats and Sheep Steven C. Hess, Dirk H. Van Vuren, and Gary W. Witmer CONTENTS Origin, Ancestry, and Domestication .....................................................................289 Forage and Water Needs ........................................................................................290 Liberation -

New World Goat Populations Are a Genetically Diverse Reservoir For

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN New world goat populations are a genetically diverse reservoir for future use Received: 20 July 2018 Tiago do Prado Paim 1,2, Danielle Assis Faria1, El Hamidi Hay3, Concepta McManus1, Accepted: 30 October 2018 Maria Rosa Lanari4, Laura Chaverri Esquivel5, María Isabel Cascante5, Esteban Jimenez Alfaro5, Published: xx xx xxxx Argerie Mendez6, Olivardo Faco7, Kleibe de Moraes Silva7, Carlos Alberto Mezzadra8, Arthur Mariante9, Samuel Rezende Paiva9 & Harvey D. Blackburn10 Western hemisphere goats have European, African and Central Asian origins, and some local or rare breeds are reported to be adapted to their environments and economically important. By-in-large these genetic resources have not been quantifed. Using 50 K SNP genotypes of 244 animals from 12 goat populations in United States, Costa Rica, Brazil and Argentina, we evaluated the genetic diversity, population structure and selective sweeps documenting goat migration to the “New World”. Our fndings suggest the concept of breed, particularly among “locally adapted” breeds, is not a meaningful way to characterize goat populations. The USA Spanish goats were found to be an important genetic reservoir, sharing genomic composition with the wild ancestor and with specialized breeds (e.g. Angora, Lamancha and Saanen). Results suggest goats in the Americas have substantial genetic diversity to use in selection and promote environmental adaptation or product driven specialization. These fndings highlight the importance of maintaining goat conservation programs and suggest an awaiting reservoir of genetic diversity for breeding and research while simultaneously discarding concerns about breed designations. Unlike other livestock species, goats are unique in terms of their function and environments where they are uti- lized. -

View of the Bio- Et Al

Guo et al. Genet Sel Evol (2019) 51:70 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-019-0512-4 Genetics Selection Evolution RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Comparative genome analyses reveal the unique genetic composition and selection signals underlying the phenotypic characteristics of three Chinese domestic goat breeds Jiazhong Guo1†, Jie Zhong1†, Li Li1, Tao Zhong1, Linjie Wang1, Tianzeng Song2 and Hongping Zhang1* Abstract Background: As one of the important livestock species around the world, goats provide abundant meat, milk, and fber to fulfll basic human needs. However, the genetic loci that underlie phenotypic variations in domestic goats are largely unknown, particularly for economically important traits. In this study, we sequenced the whole genome of 38 goats from three Chinese breeds (Chengdu Brown, Jintang Black, and Tibetan Cashmere) and downloaded the genome sequence data of 30 goats from fve other breeds (four non-Chinese and one Chinese breed) and 21 Bezoar ibexes to investigate the genetic composition and selection signatures of the Chinese goat breeds after domestication. Results: Based on population structure analysis and FST values (average FST 0.22), the genetic composition of Chengdu Brown goats difers considerably from that of Bezoar ibexes as a result= of geographic isolation. Strikingly, the genes under selection that we identifed in Tibetan Cashmere goats were signifcantly enriched in the categories hair growth and bone and nervous system development, possibly because they are involved in adaptation to high- altitude. In particular, we found a large diference in allele frequency of one novel SNP (c.-253G>A) in the 5′-UTR of FGF5 between Cashmere goats and goat breeds with short hair. -

Rarity, Trophy Hunting and Ungulates L

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Rarity, trophy hunting and ungulates L. Palazy1,2, C. Bonenfant1, J. M. Gaillard1 & F. Courchamp2 1 Biometrie´ et Biologie E´ volutive, Villeurbanne, France 2 Ecologie, Systematique´ et Evolution, Orsay, France Keywords Abstract anthropogenic Allee effect; conservation; hunting management; trophy price; The size and shape of a trophy constitute major determinants of its value. mammals. We postulate that the rarity of a species, whatever its causes, also plays a major role in determining its value among hunters. We investigated a role for an Correspondence Anthropogenic Allee effect in trophy hunting, where human attraction to rarity Lucille Palazy. Current address: UMR CNRS could lead to an over-exploitative chain reaction that could eventually drive the 5558, Univ Lyon 1, 43 bd 11 nov, 69622 targeted species to extinction. We performed an inter-specific analysis of trophy Villeurbanne cedex, France. prices of 202 ungulate taxa and quantified to what extent morphological char- Tel: +33 4.72.43.29.35 acteristics and their rarity accounted for the observed variation in their price. We Email: [email protected] found that once location and body mass were accounted for, trophies of rare species attain higher prices than those of more common species. By driving trophy Editor: Iain Gordon price increase, this rarity effect may encourage the exploitation of rare species Associate Editor: John Linnell regardless of their availability, with potentially profound consequences for populations. Received 24 January 2011; accepted 16 May 2011 doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2011.00476.x Introduction et al., 1997). Moreover, the current worldwide trend of increasing wealth, in particular in the Middle East, Russia Over-exploitation of natural resources by humans is one and China (Dubois & Laurent, 1998; Guriev & Rachinsky, of the main causes of the current and dramatic loss of 2009), is likely to be paralleled by a growth in demand for biodiversity (Kerr & Currie, 1995; Burney & Flannery, sport hunting.