Number and Size of Last-Glacial Missoula Floods in the Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Surficial Geologic Map of the Lenore Quadrangle, Nez Perce County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL WEB MAP 14 MOSCOW-BOISE-POCATELLO OTHBERG, BRECKENRIDGE, AND WEISZ Disclaimer: This Digital Web Map is an informal report and may be revised and formally published at a later time. Its content and format S URFICIAL G EOLOGIC M AP OF THE L ENORE Q UADRANGLE, N EZ P ERCE C OUNTY, I DAHO may not conform to agency standards. Kurt L. Othberg, Roy M. Breckenridge, and Daniel W. Weisz 2003 Qac CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Qls Qls Qcb Qcb Surficial Latah Columbia River QTlbr Deposits Formation Basalt Qls m Qac Qam Qoam Qas Qac HOLOCENE QTlbr Qad Qls Qcb Qcg Qm 13,000 years Qad Qag QUATERNARY PLEISTOCENE QTlbr QTlbr Qac Qls QTlbr Qac PLIOCENE TERTIARY Qac Tl Tcb MIOCENE Qcb QTlbr INTRODUCTION Qcg Colluvium from granitic and metamorphic rocks (Holocene and Pleistocene)— Primarily poorly sorted muddy gravel composed of angular and subangular pebbles, cobbles, and boulders in a matrix of sand, silt, and clay. Emplaced The surficial geologic map of the Lenore quadrangle identifies earth materials by gravity movements in Bedrock Creek canyon where there are outcrops on the surface and in the shallow subsurface. It is intended for those interested of pre-Tertiary granitic rocks and quartzite. Includes local debris-flow deposits in the area's natural resources, urban and rural growth, and private and and isolated rock outcrops. Includes colluvium and debris-flow deposits Qac public land development. The information relates to assessing diverse QTlbr from the upslope basalt section, and areas of thin loess (typically less than conditions and activities, such as slope stability, construction design, sewage 5 feet). -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

Sculpted by Floods Learning Resource Guide Overview

Sculpted by Floods Learning Resource Guide Overview: KSPS’s Sculpted by Floods tells the story of the ice age floods in the Pacific Northwest. It is a story of the earth's power, scientific discovery and human nature - one touted by enthusiasts as the greatest story left untold. During the last ice age, floods flowing with ten times the volume of all the world's current rivers combined inundated the Northwest. What they left behind was a unique landscape that citizens of the Pacific Northwest call home. Subjects: Earth Science, Geology, History, Pacific Northwest History Grade Levels: 6-8 Materials: Lesson handouts, laptops/computers Learning Guide Objectives: Define the following vocabulary terms and use them orally and in writing: glacier, flood, cataracts, landform, canyon, dam. Analyze how floods can create landforms and shape a region’s landscape, using the Missoula Floods as a case study. Next Generation Science Standards MS-ESS2-2. Construct an explanation based on evidence for how geoscience processes have changed Earth’s surface at varying time and spatial scales. Washington State History Standards EALR 4: HISTORY: 3.1. Understands the physical characteristics, cultural characteristics, and location of places, regions, and spatial patterns on the Earth’s surface Common Core English Language Arts Anchor & Literacy in History/Social Studies Standards CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.4. Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. -

Washington's Channeled Scabland

t\D l'llrl,. \·· ~. r~rn1 ,uR\fEY Ut,l\n . .. ,Y:ltate" tit1Washington ALBEIT D. ROSEWNI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Dlnctor DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By J HARLEN BRETZ 9TAT• PIUHTIHO PLANT ~ OLYMPIA, WASH., 1"511 State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By .T HARLEN BRETZ l•or sate by Department or Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. FOREWORD Most travelers who have driven through eastern Washington have seen a geologic and scenic feature that is unique-nothing like it is to be found anywhere else in the world. This is the Channeled Scab land, a gigantic series of deeply cut channels in the erosion-resistant Columbia River basalt, the rock that covers most of the east-central and southeastern part of the state. Grand Coulee, with its spectac ular Dry Falls, is one of the most widely known features of this ex tensive set of dry channels. Many thousands of travelers must have wondered how this Chan neled Scabland came into being, and many geologists also have speculated as to its origin. Several geologists have published papers outlining their theories of the scabland's origin, but the geologist who has made the most thorough study of the problem and has ex amined the whole area and all the evidence having a bearing on the problem is Dr. J Harlen Bretz. Dr. -

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 X 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood 2012 Idaho Geological Survey Third Floor, Morrill Hall University of Idaho Geologic Map 49 Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 2012 Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood INTRODUCTION 43˚ 115˚ The geology in the 1:100,000-scale Twin Falls 30 x 23 13 18 7 8 25 60 minute quadrangle is based on field work conduct- ed by the authors from 2002 through 2005, previous 24 17 14 16 19 20 26 1:24,000-scale maps published by the Idaho Geological Survey, mapping by other researchers, and compilation 11 10 from previous work. Mapping sources are identified 9 15 12 6 in Figures 1 and 2. The geologic mapping was funded in part by the STATEMAP and EDMAP components 5 1 2 22 21 of the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Cooperative 4 3 42˚ 30' Geologic Mapping Program (Figure 1). We recognize 114˚ that small map units in the Snake River Canyon are dif- 1. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 1995a 15. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005a ficult to identify at this map scale and we direct readers 2. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 16. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005b to the 1:24,000-scale geologic maps shown in Figure 1. 1995b; Othberg and others, 2005 17. Kauffman and others, 2005a 3. -

Chapter 85. the Example of the Lake Missoula Flood

Chapter 85 The Example of the Lake Missoula Flood As already noted, uniformitarian hypotheses rarely, if ever, can be supported by extensive geological evidence. Part of this is due to the nature of the features, since they originated in the past. The same charge could be leveled against Flood explanations. However, geomorphological evidence for the Retreating Stage of the Flood is strong, as this ebook shows. Whereas uniformitarian scientists have to invent speculative secondary hypotheses to salvage their paradigm in the light of conflicting evidence, the Flood paradigm does not need to invent secondary hypotheses, because the evidence is consistent with the paradigm. Furthermore, the Flood paradigm has an example of how a well-substantiated catastrophic flood at the peak of the Ice Age created a water and wind gap.1 The Lake Missoula flood (earlier called the Spokane or the Bretz flood) demonstrates catastrophic floods can easily produce water and wind gaps. Figure 85.1. Glacial Lake Missoula as shown on a kiosk sign at Lake Pend Oreille. 1 Oard, M.J., 2004. The Missoula Flood Controversy and the Genesis Flood, Creation Research Society Monograph No. 13, Chino Valley, AZ. The Lake Missoula Flood One of the largest lakes ever ponded by an ice dam was glacial Lake Missoula (Figure 85.1). After this lake deepened to 2,000 feet (610 m) at the dam site in northern Idaho, the bursting ice dam initiated one of the largest floods on earth, except that described in Genesis. Glacial Lake Missoula contained 540 mi3 (2,210 km3) of water and emptied in two days. -

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah What is the origin of the Great Salt Lake? o After the Lake Bonneville flood, the Great Basin gradually became warmer and drier. Lake Bonneville began to shrink due to increased evaporation. Today's Great Salt Lake is a large remnant of Lake Bonneville, and occupies the lowest depression in the Great Basin. Who discovered Great Salt Lake? o The Spanish missionary explorers Dominguez and Escalante learned of Great Salt Lake from the Native Americans in 1776, but they never actually saw it. The first white person known to have visited the lake was Jim Bridger in 1825. Other fur trappers, such as Etienne Provost, may have beaten Bridger to its shores, but there is no proof of this. The first scientific examination of the lake was undertaken in 1843 by John C. Fremont; this expedition included the legendary Kit Carson. A cross, carved into a rock near the summit of Fremont Island, reportedly by Carson, can still be seen today. Why is the Great Salt Lake salty? o Much of the salt now contained in the Great Salt Lake was originally in the water of Lake Bonneville. Even though Lake Bonneville was fairly fresh, it contained salt that concentrated as its water evaporated. A small amount of dissolved salts, leached from the soil and rocks, is deposited in Great Salt Lake every year by rivers that flow into the lake. About two million tons of dissolved salts enter the lake each year by this means. Where does the Great Salt Lake get its water, and where does the water go? o Great Salt Lake receives water from four main rivers and numerous small streams (66 percent), direct precipitation into the lake (31 percent), and from ground water (3 percent). -

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Document, 2012

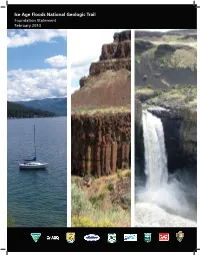

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Statement February 2014 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................................2 Purpose of this Foundation Statement.................................................................................2 Development of this Foundation Statement........................................................................2 Elements of the Foundation Statement...............................................................................3 Trail Description.......................................................................................................................4 Map..........................................................................................................................................6 Trail Purpose.......................................................................................................................................8 Trail Signifcance................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Resources and Values.................................................................................................12 Primary Interpretive Themes............................................................................................................22 -

The Holocene

The Holocene http://hol.sagepub.com The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman The Holocene 2009; 19; 143 DOI: 10.1177/0959683608098958 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/19/1/143 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Holocene can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hol.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/19/1/143 Downloaded from http://hol.sagepub.com at University of Missouri-Columbia on January 13, 2009 The Holocene 19,1 (2009) pp. 143–150 The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman* (Department of Anthropology, 107 Swallow Hall, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia MO 65211, USA) Received 9 May 2008; revised manuscript accepted 30 June 2008 Abstract: Historical data are incomplete regarding the presence/absence and distribution of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington State. Palaeozoological (archaeological and palaeontological) data indicate bighorn were present in many areas there during most of the last 10 000 years. Bighorn occupied the xeric shrub-steppe habitats of the Channeled Scablands, likely because the Scablands provided the steep escape terrain bighorn prefer. The relative abundance of bighorn is greatest during climatically dry intervals and low during a moist period. Bighorn remains tend to increase in relative abundance over the last 6000 years. -

Irrigation and Streamflow Depletion in Columbia River Basin Above the Dalles, Oregon

Irrigation and Streamflow Depletion in Columbia River Basin above The Dalles, Oregon Bv W. D. SIMONS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1220 An evaluation of the consumptive use of water based on the amount of irrigation UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1953 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose and scope....................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgments......................................................................................................... 3 Irrigation in the basin......................................................................................................... 3 Historical summary...................................................................................................... 3 Legislation................................................................................................................... 6 Records and sources for data..................................................................................... 8 Stream -

The Missoula Flood

THE MISSOULA FLOOD Dry Falls in Grand Coulee, Washington, was the largest waterfall in the world during the Missoula Flood. Height of falls is 385 ft [117 m]. Flood waters were actually about 260 ft deep [80 m] above the top of the falls, so a more appropriate name might be Dry Cataract. KEENAN LEE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES GOLDEN COLORADO 80401 2009 The Missoula Flood 2 CONTENTS Page OVERVIEW 2 THE GLACIAL DAM 3 LAKE MISSOULA 5 THE DAM FAILURE 6 THE MISSOULA FLOOD ABOVE THE ICE DAM 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Eddy Narrows 6 Catastrophic Flood Features in Perma Narrows 7 Catastrophic Flood Features at Camas Prairie 9 THE MISSOULA FLOOD BELOW THE ICE DAM 13 Rathdrum Prairie and Spokane 13 Cheny – Palouse Scablands 14 Grand Coulee 15 Wallula Gap and Columbia River Gorge 15 Portland to the Pacific Ocean 16 MULTIPLE MISSOULA FLOODS 17 AGE OF MISSOULA FLOODS 18 SOME REFERENCES 19 OVERVIEW About 15 000 years ago in latest Pleistocene time, glaciers from the Cordilleran ice sheet in Canada advanced southward and dammed two rivers, the Columbia River and one of its major tributaries, the Clark Fork River [Fig. 1]. One lobe of the ice sheet dammed the Columbia River, creating Lake Columbia and diverting the Columbia River into the Grand Coulee. Another lobe of the ice sheet advanced southward down the Purcell Trench to the present Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho and dammed the Clark Fork River. This created an enormous Lake Missoula, with a volume of water greater than that of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined [530 mi3 or 2200 km3].