The Intercourse Between the United States and Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism*

Journalism and Mass Communication, Mar.-Apr. 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 89-101 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2020.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism* WANG Hai, YU Qian, LIANG Wei-ping Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Joseph Heco, with the original Japanese name of Hamada Hikozo, played an active role in the diplomatic, economic, trade, and cultural interactions between the United States and Japan in the 1850s and 1860s. Being rescued from a shipwreck by an American freighter and taken to San Francisco in the 1850s, Heco had the chance to experience the advanced industrial civilization. After returning to Japan, he followed the example of the U.S. newspapers to start the first Japanese newspaper Kaigai Shimbun (Overseas News), introducing Western ideas into Japan and enabling Japanese people under the rule of the Edo bakufu/shogunate to learn about the great changes taking place outside the island. In the light of the historical background of the United States forcing Japan to open up, this paper expounds on Joseph Heco’s life experience and Kaigai Shimbun, the newspaper he founded, aiming to explain how Heco, as the “father of Japanese journalism”, promoted the development of Japanese newspaper industry. Keywords: Joseph Heco (Hamada Hikozo), Kaigai Shimbun, origin of Japanese journalism Early Japanese newspapers originated from the “kawaraban” (瓦版) at the beginning of the 17th century. In 1615, this embryonic form of newspapers first appeared in the streets of Osaka. This single-sided leaflet-like thing was printed irregularly and was made by printing on paper with tiles which was carved with pictures and words and then fired and shaped. -

Commodore Perry's Black Ships

Commodore Perry’s Black ships and the 150th Anniversary of U.S.–Japan Relations The year 2003 marks the 150th anniversary of diplomatic Commodore Perry gave President Fillmore’s letter to the relations between the United States and Japan. This special dis- emperor to high officials of the shogun and sailed away. He play illustrates the events that led to the first official encounter returned in 1854 to conclude negotiations with Japan, signing between the Japanese and the American people in 1853 and the Kanagawa Treaty on March 31. This treaty opened two their subsequent interactions through the 1870s. ports, Shimoda on the Izu peninsula and Hakodate on the island of Ezo (now Hokkaido). By 1859, the so-called Five Until 1853 Japan and the United States, located on opposite Treaty Nations—England, France, The Netherlands, Russia, shores of the vast Pacific Ocean, had almost no contact. By and the U.S.—had all become trade partners with Japan. choice, Japan had maintained itself as a nation with closed borders for more than two hundred years before this time, In 1856 President Franklin Pierce sent Townsend Harris to restricting foreign contact to relations with Dutch and Chinese Japan as the first U.S. consul to that nation. Harris worked on traders, who were allowed access only to Nagasaki on the a draft of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the Japan- island of Kyushu. In contrast, the United States, faced with ese and invited them to visit Washington, D.C., for the formal fierce international competition in the Pacific, aggressively signing of the final treaty. -

Japan Has Always Held an Important Place in Modern World Affairs, Switching Sides From

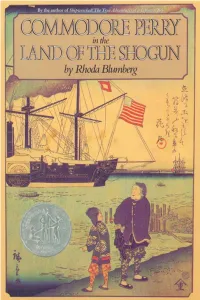

Japan has always held an important place in modern world affairs, switching sides from WWI to WWII and always being at the forefront of technology. Yet, Japan never came up as much as China, Mongolia, and other East Asian kingdoms as we studied history at school. Why was that? Delving into Japanese history we found the reason; much of Japan’s history was comprised of sakoku, a barrier between it and the Western world, which wrote most of its history. How did this barrier break and Japan leap to power? This was the question we set out on an expedition to answer. With preliminary knowledge on Matthew Perry, we began research on sakoku’s history. We worked towards a middle; researching sakoku’s implementation, the West’s attempt to break it, and the impacts of Japan’s globalization. These three topics converged at the pivotal moment when Commodore Perry arrived in Japan and opened two of its ports through the Convention of Kanagawa. To further our knowledge on Perry’s arrival and the fall of the Tokugawa in particular, we borrowed several books from our local library and reached out to several professors. Rhoda Blumberg’s Commodore Perry in the Land of the Shogun presented rich detail into Perry’s arrival in Japan, while Professor Emi Foulk Bushelle of WWU answered several of our queries and gave us a valuable document with letters written by two Japanese officials. Professor John W. Dower’s website on MIT Visualizing Cultures offered analysis of several primary sources, including images and illustrations that represented the US and Japan’s perceptions of each other. -

The" Black Ships" And" Sakoku": Commodore Matthew C. Perry's

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 969 JC 970 297 AUTHOR Finkelston, Ted TITLE The "Black Ships" and "Sakoku": Commodore Matthew C. Perry's Expedition to Japan. Asian Studies Module. INSTITUTION Saint Louis Community Coll. at Meramec, MO. PUB DATE 97 NOTE 7p.; For the related instructional modules, see JC 970 286-300 PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Community Colleges; *Course Content; Curriculum Guides; Foreign Countries; History; *History Instruction; Learning Modules; North American History; Two Year Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Japan; *Perry (Matthew C) ABSTRACT This curriculum guide presents the components of a U.S. history course examining the causes and immediate effects of the opening of Japan to American trade and diplomacy by Commodore Matthew C. Perry's 1853-1854 Japanese expedition. The first part of the guide introduces the goals of the course. Next, the student objectives of the course are listed, emphasizing the basic understanding of the following:(1) the social institutions, political institutions, economic institutions, and international relations of the Tokugawa Shogunate at the time of the expedition;(2) political and economic motivations of the Fillmore administration to send the expedition to Japan;(3) the roles of Commodore Matthew C. Perry and Masahiro Abe; and (4) the general provisions of the Treaty of Kanagawa. The student learning activities of the course are then detailed, highlighting the pre-test, an essay, group discussions, and an oral presentation. The remainder of the curriculum guide provides the method of student evaluation, the time frame for the exercise, and the pre-test instrument. Contains a bibliography. -

The Japanese Treaty Ports 1868- 1899: a Study

THE JAPANESE TREATY PORTS 1868- 1899: A STUDY THE FOREIGN SETTLEMENTS by JAMES EDWARD HOARE School of Oriental and African Studies A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London December 1970 ProQuest Number: 11010486 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010486 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The opening of Japan to foreign residence brought not only the same system of treaty ports and foreign settlements as had developed in China to solve the problem of the meeting of two very different cultures, but also led to the same people who had known the system in China operating it or living under it in Japan* The events of 1859— 1869 gave foreigners fixed ideas about the Japanese which subsequent changes could do little to alter* The foreign settlers quickly abandoned any ideas they may have had about making close contact with the Japanese* They preferred to recreate as near as possible the life they had lived in Europe or America. -

Yoshida Shōin's Encounter with Commodore Perry

63 YOSHIDA SHŌIN’S ENCOUNTER WITH COMMODORE PERRY: A REVIEW OF CULTURAL INTERACTION IN THE DAYS OF JAPAN’S OPENING* De-min Tao** The 150th anniversary of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s 1853 visit to Japan, commemorated on both sides of the Pacifi c with conferences, symposia and museum exhibitions, was a signal moment for refl ection on the complex bonds between Japan and the United States over a century and a half. NHK, the public broadcasting giant, produced a special television program on Perry; the Constitution Memorial Museum,1) as well as a number of local museums, mounted special exhibitions; several municipalities held special festivals, and scholars such as Mitani Hiroshi published new books to commemorate this historical event.2) Quite coincidentally, reports of the (re) discovery of secret letters from Yoshida Shōin (1830−1859) , focused new attention on his failed attempt to steal out of Japan through Perry’s fl agship during the Commodore’s return visit in 1854. A dozen of newspapers across Japan reported the fi nd.3) I. Shōin’s Letters to Perry Yoshida Shōin was among the most charismatic fi gures in mid-19th century Japan, “a serious scholar of Confucianism,” as Marius Jansen wrote, “a splendid teacher, and an impetuous * A slightly different version of this paper was originally included in Martin Collcutt, Katō Mikio, and Ronald Toby, eds., Japan and Its Worlds: Marius B. Jansen and the Internationalizatioin of Japanese Studies (Tokyo: I-House Press, 2007). The author would like to express his gratitude to the editors for their kind advice for refi ning the paper. -

The Copenhagen School and Japan in the Late Tokugawa Period 1853-1868

The Copenhagen School and Japan in the Late Tokugawa Period 1853-1868 History and International Relations 1 Abstract This paper analyses Japan in the late Tokugawa period using the Copenhagen School of security studies as a theoretical framework. The scope of analysis lies strictly within the time period of 1853-1868. The intended nature of the analysis is simple, and mainly aims to understand the late Tokugawa period through the lens of the Copenhagen School. It also aims to contribute to the literature of the subject area, in that it uses an interpretivist international relations theory to analyse the late Tokugawa period in Japan. The theoretical framework is applied by examining three of the Copenhagen School’s core aspects—securitization theory, regional security complex theory, and the broadening of the security agenda into five distinct sectors—and applying each of them in turn. The analysis draws from a range of examples from the given time period, largely focusing on domestic attitudes towards the prospect of modernization and Westernization, and foreign economic and imperial interests towards Japan. The analysis also considers the actions of contemporary actors at various levels of analysis, and analyses them as acts of securitization where suitable. The analysis finds that the use of the Copenhagen School as a mode of historical enquiry produces a nuanced and structured understanding of various aspects of late Tokugawa Japan. By placing the case study in the context of securitization theory, regional security complex theory, and analysing empirical examples with respect to the five sectors of security, the events of late Tokugawa Japan can be construed as a constructivist network of security dynamics, as opposed to a traditional reading of history in a simple chronological fashion. -

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND of the SHOGUN

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND OF THE SHOGUN by Rhoda Blumberg For my husband, Gerald and my son, Lawrence I want to thank my friend Dorothy Segall, who helped me acquire some of the illustrations and supplied me with source material from her private library. I'm also grateful for the guidance of another dear friend Amy Poster, Associate Curator of Oriental Art at the Brooklyn Museum. · Table of Contents Part I The Coming of the Barbarians 11 1 Aliens Arrive 13 2 The Black Ships of the Evil Men 17 3 His High and Mighty Mysteriousness 23 4 Landing on Sacred Soil The Audience Hall 30 5 The Dutch Island Prison 37 6 Foreigners Forbidden 41 7 The Great Peace The Emperor · The Shogun · The Lords · Samurai · Farmers · Artisans and Merchants 44 8 Clouds Over the Land of the Rising Sun The Japanese-American 54 Part II The Return of the Barbarians 61 9 The Black Ships Return Parties 63 10 The Treaty House 69 11 An Array Of Gifts Gifts for the Japanese · Gifts for the Americans 78 12 The Grand Banquet 87 13 The Treaty A Japanese Feast 92 14 Excursions on Land and Sea A Birthday Cruise 97 15 Shore Leave Shimoda · Hakodate 100 16 In The Wake of the Black Ships 107 AfterWord The First American Consul · The Fall of the Shogun 112 Appendices A Letter of the President of the United States to the Emperor of Japan 121 B Translation of Answer to the President's Letter, Signed by Yenosuke 126 C Some of the American Presents for the Japanese 128 D Some of the Japanese Presents for the Americans 132 E Text of the Treaty of Kanagawa 135 Notes 137 About the Illustrations 144 Bibliography 145 Index 147 About the Author Other Books by Rhoda Blumberg Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Steamships were new to the Japanese. -

Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854)

Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854) CHANG-SU HOUCHINS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • NUMBER 37 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through trie years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Observations of the First Japanese to Land in Hawai'i

HIDETO KONO KAZUKO SINOTO Observations of the First Japanese to Land in Hawai'i HIRAHARA ZENMATSU WAS A JAPANESE SEAMAN who lived among the people of the island of O'ahu for about three and a half months in 1806. Zenmatsu was a native of the province of Aki, now Hiroshima prefecture, during the reign of the Tokugawa feudal government (1603—1867). He and seven others aboard the Inawaka-maru, a small Japanese cargo ship, were shipwrecked off Japan and remained adrift in the Pacific for more than seventy days.1 An American trading ves- sel, the Tabour, sailing eastward in the northern Pacific on her return voyage from China, rescued the emaciated crew of the Inawaka-maru and deposited them on O'ahu on May 5, 1806. There they remained until August 17, when they departed from the island with the hope of returning to Japan. This essay is based on the official record of Zenmatsu's testimony compiled in a document titled Iban Hyoryu Kikokuroku.2 The testimony was given at the time Zenmatsu was summoned by Lord Asano of Hiroshima after he had finally returned to his homeland on Novem- ber 29, 1807. This occurred six months after his arrival in Nagasaki, where he was severely interrogated by officials of the bakufu (shogu- nate government). Hideto Kono and Kazuko Sinoto are members of the Joseph Heco Society of Hawai'i, which was organized in 1991 to undertake research on records of Japanese who touched the shores of Hawai'i prior to 1868, when the first group of Japanese was brought to the Islands to work on the sugar plantations. -

What He Has Seen and the People He Has Met in the Course of the Last Forty Years

The narrative of a Japanese; what he has seen and the people he has met in the course of the last forty years. By Joseph Heco. Edited by James Murdoch THE NARRATIVE OF A JAPANESE; What he has seen and the people he has met in the course of the last forty years. BY JOSEPH HECO. Edited BY JAMES MURDOCH, M.A. VOL. II. [ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.] PLATE 1. BIRD's-EYE VIEW OF THE CITY OF YEDO, AS IT APPEARED IN 1863. The narrative of a Japanese; what he has seen and the people he has met in the course of the last forty years. By Joseph Heco. Edited by James Murdoch http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.112 I. August 4th. This morning the U.S. Consulate was found to be minus its national coat-of-arms over the gate-way. This seemed to ruffle the worthy Consul very considerably. He at once issued a notice offering a reward for information leading to the apprehension and conviction of the thief who had been tampering with Uncle Sam's fowl-yard. But all to no purpose,—for what really became of that American Eagle remains a mystery even unto this day. On August 6th the English fleet under Admiral Kupper steamed out of the bay in line. It was said to be bound for Kagoshima, Satsuma's Capital, to exact reparation from that Daimio for the outrage committed by his men at Namamugi on the Tokaido in September, 1862. August 8th. The foreign representatives were notified by the Shogun's Government that Ogasawara, Dzosho-no-kami had been released from his membership of the Gorojiu.