Null by Morse: Historical Optical Communication to Smartphones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Newsletter of the Mashonaland Branch of the Zimbabwe Amateur G

The News l etter of the Ma shona land Br anch of t he Zimbabwe Amateur g~~!~- ~~~ ! ~~~ Pr esently incorporating: 1 The Newsletter of the M atabeleland Branch anti ~~~ - g~~~9~~ ~!~~~- ~~EE!~~~ ~!-~~~~~ ~ March , 1993 on ••••.••• Volume 27 - No. 4 . Editor Molly Henderson (Z21JE) All copy, information and/or quer ies should be sent to "QUA ", P.O. Box 2377, Har ar e • . C 0 N TEN T S . Page 2- Progr am f~ Mash o na l and Br. QUB Supplement . Info . on monthly meetings Page 13 - Bu l letins June Available to Members July&August QSL Bureau Soci al Function All As ian DX Contest Morse Classes. Mo cambique Ca llsigns. Page 3 - Mash.Br. Meeting Reports UK Callsign r eview January Page 14 - Swazi Hams Co nta ct SpPcemen March Ne ws Snippets: April \ J ARL - 8J9SUN Page 4 - contd. Page 15 - J AS - lb - ~irt h d a y May Ha ms in China Page 5 - Repor ter 1}4 Million J ' s Youth on the Air Uganda on str eam Erratum ZL 1 s j oin CEPT Mutare JOTA 1992 Gift from ARRL Page 6 - SAREX Report Page 16 ' ~ 1992/3 President's Report . A Few Smiles . Page 17 - contd. Page 7 - 1992 RAE (Novi ce)Exam Paper Page 18 - contd. Pag e 8 - contd'. 1993/4 Office Bearers 1992 RAE (Full ) Exam Paper Date 1994 AGM Trophy Awar ds Page 9 - contd. Page 19 - contd·. Page 10 - contd. O' Seas News - Eur opean DX Mash .Br .Meeting Re port Co ntest . October. RA DC O~ on ~S L's MATABELELAND BRANCH NEWS LETTl<' R. -

Null by Morse: Historical Optical Communication to Smartphones

Null By Morse: Historical Optical Communication to Smartphones Tom Schofield Culture Lab Tom Schofield Newcastle University King’s Walk Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU United Kingdom [email protected] ABT S RACT Null By Morse is an installation artwork that incorporates a military signaling lamp and smartphones. A series of Morse messages is transmitted automatically by the signal lamp. The messages are drawn from the history of Morse and telegraphy. A custom app for iPhone and Android uses the phone’s camera to identify the changing light levels of the lamp and the associated timings. The app then decodes the Morse and displays the message on the screen on top of the camera image. This paper discusses the artwork in relation to the following theoretical aspects: It contextualizes the position of smartphones in the history of optical communication. It proposes an approach to smartphones in media art that moves away from futurist perspectives whose fundamental approach is to seek to creatively exploit the latest features. Lastly, it discusses the interaction with the phone in the exhibition context in terms of slow technology. Introduction Null By Morse (NBM) is an installation artwork that explores optical communication on smartphones with a media archaeological approach. Media archaeology is a loose term employed to cover recent scholarship that seeks to re-examine the material history of technology to better, or at least differently, inform our evaluations of the present. Alternate histories of suppressed, neglected, and forgotten media that do not point teleologically to the present media-cultural condition as their “perfection.” Dead ends, losers, and inventions that never made it into a material product have important stories to tell [1]. -

A Design of the Traffic Lights Intelligent Control System Based on ARM and Zig Bee

2nd International Conference on Teaching and Computational Science (ICTCS 2014) A Design of the Traffic Lights Intelligent Control System Based on ARM and Zig Bee Fensu Shi Ningning Ge Beifang University of Nationalities Beifang University of Nationalities Yinchuan, China Yinchuan, China E-mail:[email protected] E-mail:[email protected] Abstract-With the rapid development of economy,Road traffic environment is changing slowly,the efficiency of the people and car traffic is becoming more and more aroused people's attention,As one of important infrastructure of road network,traffic lights have a great impact on traffic efficiency.In the traditional traffic lights control system,the control of people and Car traffic was through relatively reasonable fixed lights switch time,after the traffic statistics, analysis of the history of road intersections.This can lead to reduce the traffic efficiency,such as,there is a large flow in the red light direction but a small flow in the green light direction at the same time,Besides,The traditional control system adopts embedded wire method on the system Figure 1. system structure arrangement mostly,This means the high cost in maintenance and maintenance.On the basis of retain fixed III. THE DESIGN OF CONTROL UNIT switching time,This design scheme based on ARM, Zig-bee ARM main control board uses the samsung’s S3C2440 wireless network technology and magnetic sensors to chip, the S3C2440 is developed with ARM920T core, a improve the traffic efficiency through the real-time 32-bit RISC processor designed by Advanced RISC collection,analysis on the road traffic,according to the Machines[2],CPU frequency up to 533MHz.It integrates results of real-time adjust the traffic lights control strategy. -

A Wireless Communication Using Bubls

International Journal of Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology (IJLTET) A Wireless Communication using Bubls Ashwini.B.Halakerimath Department of Computer Science and Engineering AGMRCET-Varur, Hubli, Karnataka, India Sneha.Vasudev. Dhage Department of Computer Science and Engineering AGMRCET-Varur, Hubli, Karnataka, India Abstract- -This article presents a secure wireless communication using Morse algorithm explicitly the setup includes system connected with Relay/Optocoupler. Morse code algorithm is used to convert simple sentences to dash (“-“) and dots (”.”) .The setup includes bulb whose intensity varies based on input character. And webcam facing opposite side bulb. When the character is typed Morse code generator encodes it and decodes at opposite side. So as bulb blink, webcam detects it and through simple threshold based video processing and the interface translates the blinks back to sentences. The same arrangement is placed at the other side. Communication is possible only between authenticated users. This sort of communication can’t be decoded, no airtel or Google can store a copy of it so great for security. Keywords – Morse code encoding, decoding. I. INTRODUCTION Wireless communication is a transfer of information between two points that are not connected by electrical conductors. It allows a secure means of communication only between authenticated users. Image and the database of the authenticated users are stored on both systems, when an user tries to communicate the identity of the user is compared with already -

A Robust Real-Time Automatic Recognition Prototype for Maritime Optical Morse-Based Communication Employing Modified Clustering Algorithm

applied sciences Article A Robust Real-Time Automatic Recognition Prototype for Maritime Optical Morse-Based Communication Employing Modified Clustering Algorithm , Xiaozheng Wang y, Minglun Zhang * y, Hongyu Zhou, Xinglong Lin and Xiaomin Ren State Key Laboratory of Information Photonics and Optical Communications, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing 100876, China; [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (X.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally. y Received: 31 December 2019; Accepted: 7 February 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: In maritime communications, the ubiquitous Morse lamp on ships plays a significant role as one of the most common backups to radio or satellites just in case. Despite the advantages of its simplicity and efficiency, the requirement of trained operators proficient in Morse code and maintaining stable sending speed pose a key challenge to this traditional manual signaling manner. To overcome these problems, an automatic system is needed to provide a partial substitute for human effort. However, few works have focused on studying an automatic recognition scheme of maritime manually sent-like optical Morse signals. To this end, this paper makes the first attempt to design and implement a robust real-time automatic recognition prototype for onboard Morse lamps. A modified k-means clustering algorithm of machine learning is proposed to optimize the decision threshold and identify elements in Morse light signals. A systematic framework and detailed recognition algorithm procedure are presented. The feasibility of the proposed system is verified via experimental tests using a light-emitting diode (LED) array, self-designed receiver module, and microcontroller unit (MCU). -

Ccitt Itu-T 1956 2006 50Years

International Telecommunication Union 1956 0YEARS 2006 1 505 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE CCITT ITU-T 1956 2006 50YEARS 20 July 2006 www.itu.int/ITU-T/50/ CCITT / ITU-T 1956 - 2006 Etymology Telecommunication is the communication of information over a distance and the term is commonly used to refer to communication using some type of signalling or the transmission and reception of electromagnetic energy. The word comes from a combination of the Greek tele, meaning ‘far’, and the Latin communicatio- nem, meaning to impart, to share – literally: to make common. It is the discipline that studies the principles of transmitting information and the methods by which that information is delivered, such as print, radio or television, etc. Visual/optical telegraphs Early forms of telecommunication Telecommunications predate the tele- and stimulated Lord George Murray to Boston, and its purpose was to transmit phone. The first forms of telecommu- propose a system of visual telegraphy to news about shipping. nication were optical telegraphs using the British Admiralty. A chain of 15 tow- visual means of transmission, such as er stations was set up for the Admiralty In the late 19th century, the British Roy- smoke signals and beacons, and have between London and Deal at a cost of al Navy pioneered the use of the Aldis, existed since ancient times. nearly GBP 4 000; others followed to or signal lamp, which, using a focused Portsmouth, Yarmouth and Plymouth. lamp, produced pulses of light in Morse A significant telecommunication de- code. Invented by A.C.W Aldis, the velopment took place in the late eigh- In the United States, the first visual tele- lamps were used until the end of the 2 teenth century with the invention of graph based on the semaphore principle 20th century and were usually equipped semaphore. -

LED Traffic Signal Lamp Characterisitics State Job No

LED Traffic Signal Lamp Characterisitics State Job No. 14748(0) Final Report Prepared by: James C. Gilfert Principal Investigator and Ted A. Gilfert May 2002 Prepared in cooperation with the Ohio Department of Transportation and the US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration Athens Technical Specialists, Inc. 8157 US Route 50 Athens, Ohio 45701 1 2 Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge The support and assistance provided by the members of the Ohio Department of Transportation, Office of Traffic Engineering during the course of this project. Specifically, David Holstein, Satya Goyal, Rodger Dunn, Homer Suter, Wally Richardson, Mike Teaford, Mike Wotring, and Ed Vincent should be recognized as contributors to the overall result. Disclaimer Statement The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Ohio Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Copyright Notice This report is copyright 2002, Athens Technical Specialists, Inc. All rights are reserved, and duplication without written permission from Athens Technical Specialists, Inc. (except by the State of Ohio or the US Federal Highway Administration for official purposes) is prohibited by Federal Law. Acquisition Notice For copies of this report, contact: Ohio Department of Transportation Office of Research and Development (614) 644-8173 [email protected] 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction and Background………………………………………….5 II. Research Objectives: The Compatibility Issue…………………….6 III. Research Approach: Defining Test Procedures…………………...7 IV. -

WB1711 Layout 1

The Wave Bender November 2017 KC8SPF AWARD WINNING NEWSLETTER WRARC PREZ SEZ The peace race is behind us and so ends our busy Public Service Sea- son. I want to thank all those that came out and assisted with the race. It was a beautiful day, and we had no serious issues during the race so all in all it was a very successful outing again. We also had a test session at the Red Cross office on Belmont Avenue, and had one operator upgrade his ticket to Extra from General. Our con- gratulations go out to Scott Griffin, KE8HT, on his upgrade. I want to thank the VEs that came out to assist. Now to the most important item in my little missive this month, the upcoming election, this is the single most important issue for the members of WRARC. It is in your hands who will run our club for the next two years. If there is anyone out there that feels the urge run for office, you still have the opportunity to get your name on the ballot. At the very least we need to see all the members out for the election. It has been my pleasure to serve as your president for the last two years, and would like to thank all the officers and trustees that made my job much easier than it could have been, I appreciate and am proud of every one of them for their dedication and service to WRARC. I hope to see all of you out to vote at our next meeting. -

International Signaling

CHAPTER 6 INTERNATIONAL SIGNALING In wartime and peacetime, communications are language whenever language difficulties do not exist. necessary between U.S. Navy ships and merchantmen The Code consists of four chapters, an appendix, and sailing throughout the world. Vessels of many nations two indexes: come in contact with one another, exchanging 1. Chapter l—Signaling Instructions messages of varying degrees of importance. 2. Chapter 2—General Signal Code This chapter discusses some of the facets of international signaling, such as the manner of calling 3. Chapter 3—Medical Signal Code and answering, message construction, and use of 4. Chapter 4—Distress and Lifesaving Signals and procedure signals and signs. International signaling Radiotelephone Procedures procedures are in many respects similar to those used by allied naval units. Every signalman must be aware, 5. Appendix—U.S/Russia Supplementary Signals however, there are significant differences. for Naval Vessels When communicating with a merchantman, you 6. Indexes—Signaling Instructions and General must remember to use international procedure. Signal Code, and Medical Signal Code Merchantmen do not have access to all of our publications, nor are they required to know Navy DEFINITIONS procedure. So take a little extra time and learn how to communicate with merchantmen. When a man-of-war and a merchant ship desire to Much of the information you will need to know to communicate, it is extremely important for those communicate with merchantmen is contained in the involved in the use of the Code to follow the International Code of Signals, Pub 102. prescribed terminology. The following terms have the meanings indicated: SIGNALING INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

Transportation-Markings Database: Railway Signals, Signs, Marks & Markers

T-M TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS & MARKERS 2nd Edition Brian Clearman MOllnt Angel Abbey 2009 TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS, MARKERS TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: RAILWAY SIGNALS, SIGNS, MARKS, MARKERS Part Iiii, Second Edition Volume III, Additional Studies Transportation-Markings: A Study in Communication Monograph Series Brian Clearman Mount Angel Abbey 2009 TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS A STUDY IN COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPH SERIES Alternate Series Title: An Inter-modal Study ofSafety Aids Alternate T-M Titles: Transport ration] Mark [ing]s/Transport Marks/Waymarks T-MFoundations, 5th edition, 2008 (Part A, Volume I, First Studies in T-M) (2nd ed, 1991; 3rd ed, 1999, 4th ed, 2005) A First Study in T-M' The US, 2nd ed, 1993 (part B, Vol I) International Marine Aids to Navigation, 2nd ed, 1988 (Parts C & D, Vol I) [Unified 1st Edition ofParts A-D, 1981, University Press ofAmerica] International Traffic Control Devices, 2nd ed, 2004 (part E, Vol II, Further Studies in T-M) (lst ed, 1984) International Railway Signals, 1991 (part F, Vol II) International Aero Navigation, 1994 (part G, Vol II) T-M General Classification, 2nd ed, 2003 (Part H, Vol II) (lst ed, 1995, [3rd ed, Projected]) Transportation-Markings Database: Marine, 2nd ed, 2007 (part Ii, Vol III, Additional Studies in T-M) (1 st ed, 1997) TCD, 2nd ed, 2008 (Part Iii, Vol III) (lst ed, 1998) Railway, 2nd ed, 2009 (part Iiii, Vol III) (lst ed, 2000) Aero, 1st ed, 2001 (part Iiv) (2nd ed, Projected) Composite Categories -

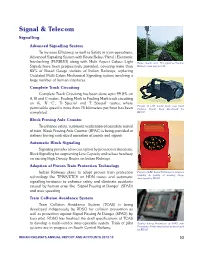

Signal & Telecom

Signal & Telecom Signalling: Advanced Signalling System To increase Efficiency as well as Safety in train operations, Advanced Signaling System with Route Relay / Panel / Electronic Interlocking (PI/RRI/EI) along with Multi Aspect Colour Light Rains, clouds, mist - This signal on Konkan Signals have been progressively provided, covering more than Railway route enjoys it all 85% of Broad Gauge stations of Indian Railways, replacing Outdated Multi Cabin Mechanical Signaling system involving a large number of human interfaces. Complete Track Circuiting Complete Track Circuiting has been done upto 99.8% on A, B and C routes. Fouling Mark to Fouling Mark track circuiting on ‘A’, ‘B’ ‘C’, ‘D Special’ and ‘E Special’ routes, where Picture of LED based torch cum hand permissible speed is more than 75 kilometers per hour has been flashing Signal lamp—developed by completed. RDSO Block Proving Axle Counter To enhance safety, automatic verification of complete arrival of train, Block Proving Axle Counter (BPAC) is being provided at stations having centralized operation of points and signals. Automatic Block Signaling Signaling provides a low cost option by provision of Automatic Block Signalling for augmenting Line Capacity and reduce headway on existing High Density Routes on Indian Railways. Adoption of Proven Train Protection Technology Indian Railways plans to adopt proven train protection Picture of LED based Tail lamps to improve visibility & quality of existing lamp- technology like TPWS/ETCS on HDN routes and automatic developed by RDSO signalling territories to enhance safety and eliminate accidents caused by human error like ‘Signal Passing at Danger’ (SPAD) and over speeding. Train Collision Avoidance System Train Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) is being developed indigenously by RDSO for collision prevention as well as protection against Signal Passing At Danger (SPAD) by loco pilot. -

FM 24-5, Basic Field Manual, Signal Communication, Is Published for the Information and Guidance of All Concerned

MHI FM 24-5 Copy 3 WAR DEPARTMENT BASIC FIELD MANUAL SIGNAL COMMUNICATION October 19, 1942 coPY - NOTE.-This is not a revision. This manual contains only C 1, 31 July 1943, C 2, 30 August 1913, and C 3, 20 September 1943, to the 19 October 1942 edition placed at the back following the original text, and will not be issued to individualis possessing that edition. FM 24-5 BASIC FIELD MANUAL SIGNAL COMMUNICATION NOTE-This is not a revision. This manual contains only C 1, 31 July 1943, C 2, 30 August 1943, and C 3, 20 September 1943, to the 19 October 1942 edition placed at the back following the original text, and will not be issued to individuals possessing that edition. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1942 WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, October 19, 1942. FM 24-5, Basic Field Manual, Signal Communication, is published for the information and guidance of all concerned. [A. G. 062.11 (7-7-42) .] BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF WAR: G. C. MARSHALL, Chief of Staff. OFFICIAL: J. A. ULIO, Major General, The Adjutant General. DISTRIBUTION: Bn and H 1-11, 17, 18, 19 (5); C 11 (10); IC 1-7, 17, 18, 19 (10); 11 (20). (For explanation of symbols see FM 21-6.) II TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. General. Paragraphs Page SECTIoN I. General_______________________------- 1-4 1 II. Organization______________________ 5-9 2 III. Command and staff duties of signal and communication officers_________ 10-12 5 IV. Disposition of matériel_______________- -13-16 8 CHAPTEE 2. Message center. SEcrIoN I.