Stephen Page Keynote Address Apam 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Page on Nyapanyapa

— OUR land people stories, 2017 — WE ARE BANGARRA We are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for our powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music and design. Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national currently in our 28th year. Our dance technique tour of a world premiere work, performed in is forged from over 40,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra, and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. Each an international tour to maintain our global has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait reputation for excellence. Islander background, from various locations across the country. Complementing this touring roster are education programs, workshops and special performances Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres and projects, planting the seeds for the next Strait Islander communities are the heart generation of performers and storytellers. of Bangarra, with our repertoire created on Country and stories gathered from respected Authentic storytelling, outstanding technique community Elders. and deeply moving performances are Bangarra’s unique signature. It’s this inherent connection to our land and people that makes us unique and enjoyed by audiences from remote Australian regional centres to New York. A MESSAGE from Artistic Director Stephen Page & Executive Director Philippe Magid Thank you for joining us for Bangarra’s We’re incredibly proud of our role as cultural international season of OUR land people stories. -

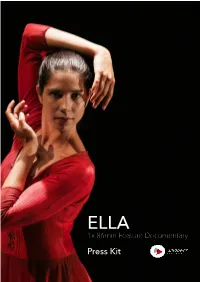

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

SOH-Annual-Report-2016-2017.Pdf

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2016-17 Contents Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2016-17 01 About Us Our History 05 Who We Are 08 Vision, Mission and Values 12 Highlights 14 Awards 20 Chairman’s Message 22 CEO’s Message 26 02 The Year’s Activity Experiences 37 Performing Arts 37 Visitor Experience 64 Partners and Supporters 69 The Building 73 Building Renewal 73 Other Projects 76 Team and Culture 78 Renewal – Engagement with First Nations People, Arts and Culture 78 – Access 81 – Sustainability 82 People and Capability 85 – Staf and Brand 85 – Digital Transformation 88 – Digital Reach and Revenue 91 Safety, Security and Risk 92 – Safety, Health and Wellbeing 92 – Security and Risk 92 Organisation Chart 94 Executive Team 95 Corporate Governance 100 03 Financials and Reporting Financial Overview 111 Sydney Opera House Financial Statements 118 Sydney Opera House Trust Staf Agency Financial Statements 186 Government Reporting 221 04 Acknowledgements and Contact Our Donors 267 Contact Information 276 Trademarks 279 Index 280 Our Partners 282 03 About Us 01 Our History Stage 1 Renewal works begin in the Joan 2017 Sutherland Theatre, with $70 million of building projects to replace critical end-of-life theatre systems and improve conditions for audiences, artists and staf. Badu Gili, a daily celebration of First Nations culture and history, is launched, projecting the work of fve eminent First Nations artists from across Australia and the Torres Strait on to the Bennelong sail. Launch of fourth Reconciliation Action Plan and third Environmental Sustainability Plan. The Vehicle Access and Pedestrian Safety 2016 project, the biggest construction project undertaken since the Opera House opened, is completed; the new underground loading dock enables the Forecourt to become largely vehicle-free. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Annual Report 2015 LETTER to MINISTER

Annual Report 2015 LETTER TO MINISTER 23 February 2016 The Honourable Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Level 15, Executive Building 100 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Premier I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2015 and audited financial statements for the Queensland Theatre Company. I certify that this annual report complies with: > the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and > the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 90 of this Annual Report or accessed at http://www.queenslandtheatre.com.au/About-Us/Publications Yours sincerely Cover photographs, Top – Bottom: 1. Boston Marriage, Amanda Muggleton, Rachel Gordon. Photography by Rob Maccoll. Emeritus Professor Richard Fotheringham FAHA 2. Ladies in Black, Kate Cole, Christen O’Leary, Naomi Price, Lucy Maunder, Deidre Rubenstein. Photography by Rob Maccall. Chair, Queensland Theatre Company 3. Happy Days, Carol Burns. Photography by Aaron Tait. 4. Oedipus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Ellen Bailey. Photography by Stephen Henry. 5. Rumour Has It, Naomi Price. Photography by Dylan Evans. 6. Grounded, Libby Munro. Photography by Stephen Henry. 7. Argus, Lauren Hayne, Nathan Booth, Matthew Seery, Anna Straker. 8. Oedipus Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Emily Burton, Toby Martin, Ellen Bailey. 9. Brisbane, Lucy Coleby, Dash Kruck. 10. Home, Margi Brown-Ash. Photography by Aaron Tait. 11. The Odd Couple, Jason Klarwein. Photography by Rob Maccoll. 12. The 7 Stages of Grieving, Chenoa Deemal. Photography by Justin Harrison. -

Annual Report 2014 1

Annual Report 2014 1 2 3 4 6 5 7 Cover photographs 1 Paul Bishop in Australia Day 2 Candy Bowers in The Mountaintop 3 Jason Klarwein and Veronica Neave in Macbeth 4 Anna McGahan in The Effect 5 Christen O’Leary in Gloria 6 Promotional photograph for Black Diggers 7 Steven Rooke in Gasp! Photography: Aaron Tait, Branco Gaica (Black Diggers) Illustration: Lauren Marriott (The Mountaintop) Letter to Minister 27 March 2015 The Honourable Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Level 15, Executive Building 100 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Premier I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2014 and audited financial statements for the Queensland Theatre Company. I certify that this annual report complies with: the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 90 of this annual report or accessed at http://www.queenslandtheatre.com.au/About-Us/Publications Yours sincerely, Professor Richard Fotheringham Chair Queensland Theatre Company Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report 1 2 Queensland Theatre Company Annual Report Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... -

Bangarra Releases 2016 Annual Report

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release 6 April 2017 Shining the spotlight on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories: a resilient Bangarra releases 2016 annual report Strong philanthropic growth, steady box office income, highly praised new Australian dance worKs, and one of The company released its 2016 annual report after the arts’ fastest growing social media communities holding their Annual General Meeting in Sydney were the highlights for Bangarra Dance Theatre in yesterday. A moderate surplus of $57,000 was 2016 amongst a year of significant adversity. achieved – but even more impressive was a 20% increase in philanthropic income, helping to reduce The company were extremely saddened by the loss of reliance on core Government funding to 38% and offset Music Director David Page, who passed away in April the increasing costs of delivering core activity. 2016. Bangarra displayed its strength and resilience by presenting a national tour of OUR land people stories The Executive Director of Bangarra, Philippe Magid, from June to September, with all 59 performances says the positive result was due to a number of factors. dedicated to his memory. Almost 34,000 people nationally attended shows in Sydney, Canberra, Perth, “An appetite for exciting and original programming Brisbane and Melbourne to see three incredible worKs: showcasing Aboriginal stories led to robust box office Nyapanyapa by Stephen Page, Miyagan by dancers income, and increasingly our marKeting has become and cousins Daniel Riley and Beau Dean Riley Smith, more focused and effective with an emphasis on digital and Macq by dancer Jasmin Sheppard. and data-driven campaigns, ” says Magid. -

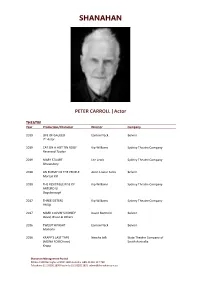

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

For All Media Enquiries, Please Contact: Anna Shapiro, Media & Communications Manager Bangarra Dance Theatre M: 0417 043 20

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release 18 November 2017 Bangarra stronger than ever in 2017 with two brand-new works Bennelong and ONES COUNTRY – the spine of our stories: now on sale! Bangarra brings two brand-new contemporary dance seasons to the stage in 2017, marking one of its biggest years to date. Charged with creativity after a successful 2016, the company is ready to do what it does best: generate engagement with all Australians and illuminate the art of storytelling. Bennelong, choreographed by Artistic Director Stephen Page will tour nationally, while ONES COUNTRY – the spine of our stories, has been commissioned especially for our second Sydney season at Carriageworks. Artistic Director Stephen Page says that 2017 will be significant for Bangarra: “Bangarra’s backbone lies in its ability to carry the power of Australia’s first cultures – blending old with new – and embracing the diversity and strength of our people. Next year we bring two transformative new seasons to the stage, which embody exactly this.” “I’m really looking forward to cultivating our storytelling in the studio and above all, sharing it nationally and internationally with Australia’s finest artists by my side.” “2016 has been challenging, but our art-form is a powerful medicine and it has helped us to heal. We will have a special celebration of our brother David Page’s life at the Sydney Opera House in June.” Says Executive Director Philippe Magid: “The company’s strength is its capacity to create inspiring and positive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences for all.” “Next year’s footprint provides us with incredible opportunities to connect with all corners of the country, with one of our biggest years of creation and delivery on record.” BENNELONG The national tour of Bennelong will premiere on 29 June at Sydney Opera House, before travelling to Canberra, Brisbane and Melbourne. -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman with Lisa Flanagan

Sydney Theatre Company Education present By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman With Lisa Flanagan Directed by Leah Purcell Teacher's Resource Kit Written and compiled by Robyn Edwards and Samantha Kosky sydneytheatre.com.au/education Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Sydney Theatre Company’s The 7 Stages of Grieving Teacher’s Notes © 2008 1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION The 7 Stages of Grieving By Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman Season 22 February – 20 March 2008 Venue Wharf 2, Sydney Theatre Company Pier 4/5 Hickson Road,Walsh Bay Touring The 7 Stages of Grieving will tour to Griffith Regional Arts Centre (2 April), Wagga Wagga Civic Theatre (4, 5, 7 April) and Albury Performing Arts Centre 9, 10 April). This tour has been made possible by Arts NSW through the ConnectED programme. Sydney Theatre Company would like to take this opportunity to warn members of the audience that this production contains names and visual representations of people recently dead, which may be distressing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. All care has been taken to acquire the appropriate permission and show all proper respect. The performance time is approximately one hour. Please note there will be no interval and latecomers will not be admitted. We respectfully ask teachers discuss theatre etiquette with students prior to attending the performance. We respectfully ask that you discuss theatre etiquette with your students prior to coming to the performance.