Different Inflections-Intercultural Dance in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Page on Nyapanyapa

— OUR land people stories, 2017 — WE ARE BANGARRA We are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for our powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music and design. Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national currently in our 28th year. Our dance technique tour of a world premiere work, performed in is forged from over 40,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra, and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. Each an international tour to maintain our global has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait reputation for excellence. Islander background, from various locations across the country. Complementing this touring roster are education programs, workshops and special performances Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres and projects, planting the seeds for the next Strait Islander communities are the heart generation of performers and storytellers. of Bangarra, with our repertoire created on Country and stories gathered from respected Authentic storytelling, outstanding technique community Elders. and deeply moving performances are Bangarra’s unique signature. It’s this inherent connection to our land and people that makes us unique and enjoyed by audiences from remote Australian regional centres to New York. A MESSAGE from Artistic Director Stephen Page & Executive Director Philippe Magid Thank you for joining us for Bangarra’s We’re incredibly proud of our role as cultural international season of OUR land people stories. -

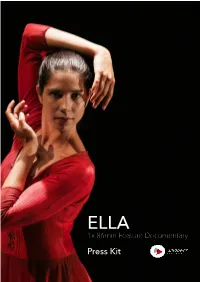

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

SOH-Annual-Report-2016-2017.Pdf

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2016-17 Contents Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2016-17 01 About Us Our History 05 Who We Are 08 Vision, Mission and Values 12 Highlights 14 Awards 20 Chairman’s Message 22 CEO’s Message 26 02 The Year’s Activity Experiences 37 Performing Arts 37 Visitor Experience 64 Partners and Supporters 69 The Building 73 Building Renewal 73 Other Projects 76 Team and Culture 78 Renewal – Engagement with First Nations People, Arts and Culture 78 – Access 81 – Sustainability 82 People and Capability 85 – Staf and Brand 85 – Digital Transformation 88 – Digital Reach and Revenue 91 Safety, Security and Risk 92 – Safety, Health and Wellbeing 92 – Security and Risk 92 Organisation Chart 94 Executive Team 95 Corporate Governance 100 03 Financials and Reporting Financial Overview 111 Sydney Opera House Financial Statements 118 Sydney Opera House Trust Staf Agency Financial Statements 186 Government Reporting 221 04 Acknowledgements and Contact Our Donors 267 Contact Information 276 Trademarks 279 Index 280 Our Partners 282 03 About Us 01 Our History Stage 1 Renewal works begin in the Joan 2017 Sutherland Theatre, with $70 million of building projects to replace critical end-of-life theatre systems and improve conditions for audiences, artists and staf. Badu Gili, a daily celebration of First Nations culture and history, is launched, projecting the work of fve eminent First Nations artists from across Australia and the Torres Strait on to the Bennelong sail. Launch of fourth Reconciliation Action Plan and third Environmental Sustainability Plan. The Vehicle Access and Pedestrian Safety 2016 project, the biggest construction project undertaken since the Opera House opened, is completed; the new underground loading dock enables the Forecourt to become largely vehicle-free. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Bangarra Releases 2016 Annual Report

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release 6 April 2017 Shining the spotlight on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories: a resilient Bangarra releases 2016 annual report Strong philanthropic growth, steady box office income, highly praised new Australian dance worKs, and one of The company released its 2016 annual report after the arts’ fastest growing social media communities holding their Annual General Meeting in Sydney were the highlights for Bangarra Dance Theatre in yesterday. A moderate surplus of $57,000 was 2016 amongst a year of significant adversity. achieved – but even more impressive was a 20% increase in philanthropic income, helping to reduce The company were extremely saddened by the loss of reliance on core Government funding to 38% and offset Music Director David Page, who passed away in April the increasing costs of delivering core activity. 2016. Bangarra displayed its strength and resilience by presenting a national tour of OUR land people stories The Executive Director of Bangarra, Philippe Magid, from June to September, with all 59 performances says the positive result was due to a number of factors. dedicated to his memory. Almost 34,000 people nationally attended shows in Sydney, Canberra, Perth, “An appetite for exciting and original programming Brisbane and Melbourne to see three incredible worKs: showcasing Aboriginal stories led to robust box office Nyapanyapa by Stephen Page, Miyagan by dancers income, and increasingly our marKeting has become and cousins Daniel Riley and Beau Dean Riley Smith, more focused and effective with an emphasis on digital and Macq by dancer Jasmin Sheppard. and data-driven campaigns, ” says Magid. -

For All Media Enquiries, Please Contact: Anna Shapiro, Media & Communications Manager Bangarra Dance Theatre M: 0417 043 20

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release 18 November 2017 Bangarra stronger than ever in 2017 with two brand-new works Bennelong and ONES COUNTRY – the spine of our stories: now on sale! Bangarra brings two brand-new contemporary dance seasons to the stage in 2017, marking one of its biggest years to date. Charged with creativity after a successful 2016, the company is ready to do what it does best: generate engagement with all Australians and illuminate the art of storytelling. Bennelong, choreographed by Artistic Director Stephen Page will tour nationally, while ONES COUNTRY – the spine of our stories, has been commissioned especially for our second Sydney season at Carriageworks. Artistic Director Stephen Page says that 2017 will be significant for Bangarra: “Bangarra’s backbone lies in its ability to carry the power of Australia’s first cultures – blending old with new – and embracing the diversity and strength of our people. Next year we bring two transformative new seasons to the stage, which embody exactly this.” “I’m really looking forward to cultivating our storytelling in the studio and above all, sharing it nationally and internationally with Australia’s finest artists by my side.” “2016 has been challenging, but our art-form is a powerful medicine and it has helped us to heal. We will have a special celebration of our brother David Page’s life at the Sydney Opera House in June.” Says Executive Director Philippe Magid: “The company’s strength is its capacity to create inspiring and positive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences for all.” “Next year’s footprint provides us with incredible opportunities to connect with all corners of the country, with one of our biggest years of creation and delivery on record.” BENNELONG The national tour of Bennelong will premiere on 29 June at Sydney Opera House, before travelling to Canberra, Brisbane and Melbourne. -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

Bangarra Dance Theatre

BENNELONG BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE Founder Principal Partner Community Partner Perth Festival acknowledges the Noongar people who continue to practise their values, language, beliefs and knowledge on their kwobidak boodjar. They remain the spiritual and cultural birdiyangara of this place and we honour and respect their caretakers and custodians and the vital role Noongar people play for our community and our Festival to flourish. BENNELONG HEATH LEDGER THEATRE | THU 6 – SUN 9 FEB | 75MINS Hear from the artists in a Q&A session after the performance on Fri 7 Feb. 50 This performance contains smoke and haze effects There is a special relationship in the performing arts between creator, performer and audience. Without any one of those elements, the ceremony of performance ceases to exist. In choosing to be here, we thank you for your act of community as we celebrate the artists on the stage and the imaginations of those who have given them environments to inhabit, words to embody and songs to sing. Perth Festival 2020 is a celebration of us – our place and our time. It wouldn’t be the same without you. Iain Grandage, Perth Festival Artistic Director FANFARE You were called to your seat tonight by The Celestial March composed by 19-year-old WAAPA student Hanae Wilding. Visit perthfestival.com.au for more information on the Fanfare project. LOOKING FOR SOMETHING TO DO AFTER THE SHOW? Venture down below here at the State Theatre Centre and slide into the late-night world of Perth Festival at Bar Underground. Open every night until late. 50 Image: -

Belong Education Kit

Belong Education Kit ©Bangarra Dance Theatre Belong Education Kit Belong Education Kit Bangarra Dance Theatre Company Company Profile Bangarra has created an extraordinary signature body of work that has secured the company’s Bangarra is Australia's premier Indigenous national and international reputation. Stephen performing arts company. Established in 1989, Page is committed to developing the next Bangarra produces distinctive dance theatre generation of Indigenous storytellers by mentoring productions that tour each year to capital cities, creative artists and providing opportunities for regional towns and remote communities of Indigenous young people. Australia. As cultural ambassadors, Bangarra presents its truly Australian contemporary Four artists-in-residence have been appointed to Indigenous theatrical experiences throughout the Bangarra in 2011: Kathy Marika, Jacob Nash, world. David Page and Frances Rings. A new Indigenous trainee program has enabled three young Under the leadership of Artistic Director Stephen Aboriginal theatre practitioners to join Bangarra for Page since 1991, Bangarra embraces, celebrates formal training and career development. and respects Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their cultures. Always uplifting and deeply moving, Bangarra unifies the past and the present by connecting traditional Indigenous culture with our contemporary lives. ©Bangarra Dance Theatre Belong Education Kit Belong Education Kit With studios based in the arts precinct at Walsh Bay in Sydney, the company has 15 dancers who come from all over Australia reflecting many Aboriginal and Torres Strait cultures. Bangarra is a significant Indigenous employer with 70% of its 34 full time staff being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander decent. The board is chaired by Larissa Behrendt who is a leading Aboriginal lawyer and academic. -

Belvoir Annual Report 2010

Belvoir Annual Report 2010 Belvoir Annual Report 2010 25 Belvoir St, Surry Hills NSW 2010 admin +61 (0)2 9698 3344 fax +61 (0)2 9319 3165 box office +61 (0)2 9699 3444 [email protected] belvoir.com.au Toby Schmitz & Robin McLeavy in Measure for Measure. Photo: Heidrun Löhr. Contents The Belvoir Story 02 Core Values, Principles and Mission 03 Chair’s Report 04 Artistic Director’s Report 06 General Manager’s Report 08 New Artistic Director’s Note 11 2010 Season and Tours 12 B Sharp 26 Creative and Artistic Development 28 Awards 29 Education 30 Board and Staff 33 Donors 34 Partners and Government Supporters 36 Financial Statements 37 Key Performance Indicators 38 Directors’ Report 40 Statement of Comprehensive Income 44 Statement of Financial Position 45 Statements of Cash Flows and Changes in Equity 46 Notes to the Financial Statements 47 Auditor’s Independence Declaration and Report 56 01 The Belvoir Story Core Values and Principles One building. • Belief in the primacy of the Six hundred people. artistic process Thousands of stories. • Clarity and playfulness in One dream. storytelling • A sense of community within the theatrical environment When the Nimrod Theatre building in Belvoir Belvoir’s position as one of Australia’s most • Responsiveness to current Street, Surry Hills, was threatened with innovative and acclaimed theatre companies demolition in 1984, more than 600 people has been determined by such landmark social and political issues – ardent theatre lovers together with arts, productions as The Diary of a Madman, The • Equality, ethical standards and entertainment and media professionals – Blind Giant is Dancing, Cloudstreet, Measure shared ownership of artistic formed a syndicate to buy the building and for Measure, Keating!, Parramatta Girls, Exit and company achievements save this unique performance space in the King, The Alchemist, Hamlet, Waiting inner-city Sydney. -

Wednesday 5 May 2021 Media Release a High Note to 2020: The

Wednesday 5 May 2021 Media Release A high note to 2020: The performing arts industry celebrates four leading lights in long-awaited Industry Achievement Awards announcement The Industry Achievement Award recipients for 2020 have been revealed and honoured: 2020 JC Williamson Award® Deborah Cheetham AO and David McAllister AM Sue Nattrass Award® Jill Smith AM and Ann Tonks AM Melbourne, Australia: Live Performance Australia (LPA) today announced and honoured four of Australia’s most celebrated live performance luminaries in a postponed 2020 Industry Achievement Awards ceremony, which took place on Wednesday 5 May at Melbourne Recital Centre. Deborah Cheetham AO and David McAllister AM have been announced as the recipients of the 2020 JC Williamson Award®, the foremost honour that the Australian live entertainment industry can bestow. In awarding the 2020 JC Williamson Award®, LPA recognises an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the Australian live entertainment and performing arts industry and shaped the future of our industry for the better. At the same event Jill Smith AM and Ann Tonks AM were revealed as the dual recipients of the 2020 Sue Nattrass Award®. This prestigious award honours exceptional service to the Australian live performance industry, shining a spotlight on people in service roles that support and drive our industry, roles that have proved particularly crucial in ensuring the sector’s survival over the past year. 2020 JC Williamson Award® Yorta Yorta woman, soprano, composer and educator Professor Deborah Cheetham AO, has been a leader and pioneer in the Australian arts landscape for more than 25 years. In 2009, Deborah established Short Black Opera with her partner Toni Lalich OAM, as a national not-for-profit opera company devoted to the development of Indigenous singers. -

The Stretton Legacy

THE STRETTON LEGACY Michelle Potter When Australian Ballet principal dancer Matthew Trent retired late in 2005 he was quoted in The Age as saying that, in the course of his career with the Australian Ballet, the period of Ross Stretton’s directorship had been the one in which he grew most as an artist. He said: That’s when I was being given my biggest opportunities. The period with Ross was the period I grew the most. I loved the repertoire.* When Stretton, the Australian Ballet’s sixth artistic director, died in June 2005, much attention was paid to analysing, belatedly perhaps, the nature of his contribution to ballet in Australia, and to the Australian Ballet in particular. Not every commentator or dancer felt that Stretton had been generous in giving opportunities, but there seemed to be widespread agreement that the expansion of the company’s repertoire was one of Stretton’s great contributions during the short period of his directorship from 1997 to mid- 2001. The works Stretton put on stage reflected, quite naturally a range of necessities as well as his particular vision. No artistic director or a repertory company such as the Australian Ballet could or would want to dispense entirely with heritage and tradition. The repertoire listed below, especially the list of works restaged from the company’s existing repertoire, makes it quite clear that Stretton cared about the classical tradition. Nor can an artistic director ever divorce him or herself from the influences that have shaped his or her life. Stretton’s repertoire reflects quite strongly the impact his time as a dancer and director in the United States had upon him, especially in the new acquisitions he made for the Australian Ballet.