Reed Mullican, Voice – 5:30 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B

omit THE PIANO STYLE OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by 1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B. M. Longview, Texas June, 1951 19139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . , . iv Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIANO AS AN INFLUENCE ON STYLE . , . , . , . , . , . ., , , 1 II. DEBUSSY'S GENERAL MUSICAL STYLE . IS Melody Harmony Non--Harmonic Tones Rhythm III. INFLUENCES ON DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS . 56 APPENDIX (CHRONOLOGICAL LIST 0F DEBUSSY'S COMPLETE WORKS FOR PIANO) . , , 9 9 0 , 0 , 9 , , 9 ,9 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY *0 * * 0* '. * 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 .9 76 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Range of the piano . 2 2. Range of Beethoven Sonata 10, No.*. 3 . 9 3. Range of Beethoven Sonata .2. 111 . , . 9 4. Beethoven PR. 110, first movement, mm, 25-27 . 10 5. Chopin Nocturne in D Flat,._. 27,, No. 2 . 11 6. Field Nocturne No. 5 in B FlatMjodr . #.. 12 7. Chopin Nocturne,-Pp. 32, No. 2 . 13 8. Chopin Andante Spianato,,O . 22, mm. 41-42 . 13 9. An example of "thick technique" as found in the Chopin Fantaisie in F minor, 2. 49, mm. 99-101 -0 --9 -- 0 - 0 - .0 .. 0 . 15 10. Debussy Clair de lune, mm. 1-4. 23 11. Chopin Berceuse, OR. 51, mm. 1-4 . 24 12., Debussy La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, mm. 32-34 . 25 13, Wagner Tristan und Isolde, Prelude to Act I, . -

The Young Debussy Darren Chase Tenor Mark Cogley Piano

t h e Y o u N g d e B u s s Y darren Chase tenor Mark Cogley piano C r e d i t s engineer: Louis Brown recorded at L. Brown Studios in New York Cover Photo of Daren Chase: David Wentworth Photo of Mark Cogley: Casey Fatchett www.albanyrecords.com TROY1221 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. 1 Beau soir (Paul Bourget) [2:25] t h e M u s i C 2 Paysage sentimentale (Paul Bourget) [3:20] 3 Voici que le printemps (Paul Bourget) [3:16] The Young Debussy comprises the songs composed by Claude Achille Debussy (1862-1918) before 4 Fleur des blés (André Girod) [2:32] his thirtieth birthday, but includes only those he thought were good enough to publish. (With these exceptions: the 1891 set Trois Poèmes de Verlaine could not be included for lack of space; the 1903 Cinq Poèmes de Charles Baudelaire Dans le jardin has been inserted in its place.) 5 Le balcon [7:41] the vocal writing in these songs varies, but in most of them there is the emphasis on the middle 6 harmonie du soir [4:23] and low range characteristic of much French vocal music. Therefore every downward transposition 7 Le jet d’eau [5:55] has the effect of thickening the texture and darkening the color Debussy had in mind. -

Student Recital

OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Department of Music Student Recital Alyssa Romanelli, soprano Joe Ritchie, piano Diehn Center for the Performing Arts Chandler Recital Hall Friday, April 21, 2017 3:00PM Program Và Godendo Go Enjoying Và godendo vezzoso e bello Joyous, graceful and lovely goes Va Godendo George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) quel ruscello la libertà. That free-flowing little brook, E tra l'erbe con onde chiare And though the grass with clear waves from Serse lieto al mare correndo và. It goes gladly running to the sea. Bel Piacere from Agrippina Bel Piacere Great Pleasure Bel piacere è godere fido amor! It is great pleasure to enjoy a faithful love! questo fà contento il cor. it pleases the heart. Nuit D’etoiles Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Di bellezza non s'apprezza Splendor is not measured by beauty Beau Soir lo splendor; Se non vien d'un fido cor. if it does not come from a faithful heart. Nuit D’etoiles Night of Stars Always True to You in My Fashion Cole Porter (1891-1964) Nuit d'étoiles, Night of stars, from Kiss Me Kate Sous tes voiles, beneath your veils, Sous ta brise et tes parfums, beneath your breeze and your perfumes, Triste lyre sad lyre Qui soupire, which is sighing, Don’t Be Afraid Rika Muranaka (b. 1972) Je rêve aux amours défunts. I dream of bygone loves. La seriene Mélancolie Serene Melancholy from Metal Gear Solid Vient éclore au fond de mon cœur, comes to blooms in the depths of my heart, John Toomey, piano Et j'entends l'âme de ma mie and I hear the soul of my beloved Tyler Harney, saxophone Tressallir dans le bois rêveur quiver in the dreaming wood. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Departmental Programs 2003

1 Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 3/20/2012 Departmental Programs 2003 Spring 2003 Seminar January 30. 2003 Trk. 2 O del mio dolce ardor (Gluck) Phylnette Harrison, mezzo-soprano Trk. 4 Deh Vieni, non tardar (from Le Nozze di Figaro) (Mozart) Katie Barnes, soprano Trk. 7 Andante (from The English Suite) (R. Bernard Fitzgerald) Acacia Cleveland, trumpet Cantata (John Carter) Audra Scott, soprano Trk. 9-12 Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child Trk. 13-14 Let Us Break Bread Together Trk. 15 In a Sentimental Mood (Duke Ellington) Christopher Mitchell, saxophone Trk. 16 Concerto No. 3 in c minor, Op. 37 (Ludwig van Beethoven) Christopher Carson, piano Seminar February 13, 2003 Trk. 1 Concerto for Trumpet (G.F. Handel) Brian Bell, trumpet Sarabande Allegro Seminar February 20, 2003 Trk. 1 Prelude (from Suite Bergamasque) (Claude Debussy) Melissa Joseph, piano Trk. 2 Meine Liebe ist Grum (Johannes Brahms) Violet Campbell, mezzo-soprano Trk. 3 Etude in a minor (Dmitri Kabalevsky) Tameka Evans, piano Trk. 4 Va godendo (from Serse) (G.F. Handel) Katie Barnes, soprano Trk. 5 Beau Soir (Claude Debussy) Erin Liggins, mezzo-soprano Trk. 6 Cantata (John Cage) Audra Scott, soprano Peter Go Ring dem Bells Seminar February 27, 2003 Trk. 1 Sonata in a minor, K. 331 (Alla Turka) (W.A. Mozart) Kenneth Clark, piano Trk. 2 Sonata No. 1 in F Major (Benedetto Marcello) Michael Riddick, tuba 2 Allegro Trk. 3 Nacht (Richard Strauss) Erin Liggins, mezzo-soprano Trk. 4 Sonata for Trumpet (Ken Kennan) Abe Williams, III, Trumpet Moderately Fast Trk. -

Eric Owens, Bass-Baritone Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Beau Soir Fleur Des Blés Craig Rutenberg, Piano Romance Nuit D’Étoiles

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, November 20, 2011, 3pm Hertz Hall Eric Owens, bass-baritone Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Beau Soir Fleur des Blés Craig Rutenberg, piano Romance Nuit d’étoiles PROGRAM Henri Duparc (1848–1933) L’Invitation au Voyage Le Manoir de Rosemonde Élégie Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) Drei Lieder nach Gedichten von Michelangelo Wohl denk ich oft Alles endet, was entstehet Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) Don Quichotte à Dulcinée Fühlt meine Seele das ersehnte Licht Chanson romanesque Chanson épique Chanson à boire Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Mein Herz ist schwer, Op. 25, No. 15 Muttertraum, Op. 40, No. 2 Der Schatzgräber, Op. 45, No. 1 Richard Wagner (1813–1883) Les Deux Grenadiers Melancholie, Op. 74, No. 6 Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Prometheus, D. 674 Fahrt zum Hades, D. 526 Gruppe aus dem Tartarus, D. 583 INTERMISSION Funded by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 16 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 17 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) a vigorous character (developed from the previ- successful bookseller in Zwickau, and he kept November 1840, two months after his wedding, Drei Lieder nach Gedichten von Michelangelo ous motive) and closes festively with triumphal abreast of the day’s most important writers Schumann created a pendant to those two song (“Three Songs on Poems by Michelangelo”) fanfares, like a flourish of trumpets sounded throughout his life. He was already aware of the cycles with the Romanzen und Balladen I, Op. -

Senior Recital: Julia Callaghan, Soprano

Ithaca College Digital Commons IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-15-2021 Senior Recital: Julia Callaghan, soprano Julia Callaghan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Callaghan, Julia, "Senior Recital: Julia Callaghan, soprano" (2021). All Concert & Recital Programs. 7979. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/7979 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons IC. SENIOR RECITAL: Julia Callaghan, soprano Muse Ye, piano Harris Andersen, harpsichord Elizabeth Carroll, cello Ford Hall Thursday, April 15th, 2021 7:00 pm Program S’altro Che Lacrime Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Le Violette Domenico Scarlatti (1843-1907) Beau Soir Claude Debussy Les Papillons (1862-1918) En Sourdine Harris Andersen, harpsichord Nuit d’Etoiles Nimmersatte Liebe Hugo Wolf Die Spröde (1860-1903) Elfenlied Der Tambour Intermission Lagrime Mie Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) Harris Andersen, harpsichord Elizabeth Carroll, cello These Strangers Jake Heggie In the Midst of Thousands (b. 1961) I Did Not Speak Out Passing Stranger Svarta Rosor Jean Sibelius Drömmen (1865-1957) Var det en dröm? Translations S'altro Che Lacrime If You Cannot Bestow S'altro che làgrime per lui non tenti, If you cannot bestow tutto il tuo piangere non gioverà. upon him anything but your tears, A questa inutile pietà che senti oh, all of your weeping will be for naught. quanto è simile la crudeltà. To this useless pity you feel, O, how similar is outright cruelty! Translation © by Andrew Schnieder Le Violette The Violets Rugiadose Odorose Violette graziose, Dewy, fragrant, charming violets, Voi vi state Vergognose, You stand there modestly, Mezzo ascose Fra le foglie, Half hidden among the leaves, E sgridate Le mie voglie, And ridicule my wishes Che son troppo ambiziose. -

L a Program for Web.Pdf

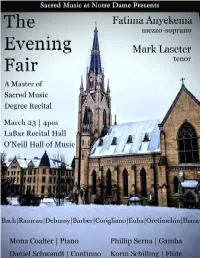

Sacred Music at Notre Dame Presents Fatima Anyekema, mezzo-soprano Mark Laseter, tenor The Evening Fair Et misericordia, from Magnificat, BWV 243 (1723) Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Fatima Anyekema, mezzo-soprano Mark Laseter, tenor Daniel Schwandt, portative organ Phillip Serna, viola da gamba Now have I fed and eaten up the rose, Op. 45 (1972) Samuel Barber Of that so sweet imprisonment (1935) 1910-1981 Solitary Hotel, Op. 41 (1968) Fatima Anyekema, mezzo-soprano Mona Coalter, piano Three Irish Folksong Settings (1988) John Corigliano I. The Salley Gardens b. 1938 II. The Foggy Dew III. She Moved Through the Fair Mark Laseter, tenor Korin Schilling, flute Beau soir (1877) Claude Debussy Fleur des bles (1880) 1862-1918 Nuit d’etoilles (1880) Fatima Anyekema, mezzo-soprano Mona Coalter, piano Pigmalion(1748) Jean-Philippe Rameau Fatal Amour 1683-1764 Règne, Amour Mark Laseter, tenor Korin Schilling, flute Phillip Serna, viola da gamba Daniel Schwandt, harpsichord Tobenu Chukwu (Praise God) Vincent Ihaza b. 1972 Ore meta (Three Friends) Akin Euba b. 1935 Omi (Water) S. K. Oretimehin b. 1980 Fatima Anyekema, mezzo-soprano Mona Coalter, piano Andrew Skiff, percussion ________________________ Saturday, March 23, 2019, 4PM LaBar Recital Hall, O’Neill Hall of Music Fatima Anyekema and Mark Laseter are students of Kiera Duffy. This recital is in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Sacred Music. Personnel Fatima Anyekema, Mezzo-soprano Mark Laseter, Tenor Mona Coalter, Collaborative Piano Daniel Schwandt, Harpsichord and Organ Phillip Serna, Viola da Gamba Korin Schilling, Flute Andrew Skiff, Percussion The piano used in this performance is a gift of David and Shari Boehnen. -

Claude-Achille Debussy (1862 – 1916)

Claude-Achille Debussy (1862 – 1916) Band 1 : L75 Suite Bergamasque, L95 Pour le piano, L100 Estampes Band 2 : L 113 Children's Corner, Einzelstücke Band 3 : L 136 Etudes Band 4 : L 110 & L111 Images Band 5 : L 117 & L123 Preludes Sämtliche Werke für Pianoforte solo Originalfassungen Band 1 : Suite bergamasque, Pour le piano, Estampes L 75 Suite Bergamasque Seite Prélude 4 10 Menuet Clair de lune 17 Passepied 23 L 95 Pour le piano Prélude 32 Sarabande 42 Toccata 45 L 100 Estampes Pagodes 58 La soirée Dans Grenade 67 Jardins sous 74 la pluie 84 Kommentare Band 2 : Einzelstücke, Children' Corner Seite Danse bohèmienne 4 L9 2 Arabesques L66 7 1. 2. 12 Mazurka L67 17 Rêverie L68 22 Tarantelle styrienne 26 (Danse) L69 Ballade (Slave) 36 L70 Valse roman- tique L71 44 Nocturne L82 49 D’un cahier d’esquisses L99 56 Masques L105 60 L’isle joyeuse L106 71 Pièce pour piano Morceau de concours 83 L108 Band 2 Children’s Corner L113 Seite Kinderecke 1.Docteur Gradus 84 ad Parnassum 2.Jimbo’s Lullaby 88 3.Serenade for 91 the Doll 4.The Snow 96 is Dancing 5.The little Shepherd 100 6.Golliwogg’s 102 Cake-walk The little Nigar 106 (Cake-walk) L114 Hommage à 108 Joseph Haydn L115 La plus que lente 112 L121 Berceuse héroïque 117 L132 Pièce sans titre 121 L133 Élégie L138 122 Kommentare 123 Band 3 : Etudes L 136 Etudes Seite 1.pour les „cinq doigts“ d’après 4 Monsieur Czerny 2. pour les Tierces 11 3. pour les Quartes 18 4. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

The University of North Carolina at Wilmington Department of Music

The University of North Carolina at Wilmington Department of Music SELECT SAXOPHONE REPERTOIRE & LEVELS First Year Method Books: The Saxophonist’s Workbook (Larry Teal) Foundation Studies (David Hite) Saxophone Scales & Patterns (Dan Higgins) Preparatory Method for Saxophone (George Wolfe) Top Tones for the Saxophone (Eugene Rousseau) Saxophone Altissimo (Robert Luckey) Intonation Exercises (Jean-Marie Londeix) Exercises: The following should be played at a minimum = 120 q • Major scales, various articulations • Single tongue on one note • Major thirds • Alternate fingerings (technique & intonation) • Single tongue on scale excerpt, tonic to dominant • Harmonic minor scales • Chromatic scale • Arpeggios in triads Vibrato (minimum = 108 for 3/beat or = 72-76 for 4/beat) q q Overtones & altissimo Jazz articulation Etude Books: 48 Etudes (Ferling/Mule) Selected Studies (Voxman) 53 Studies, Book I (Marcel Mule) 25 Daily Exercises (Klose) 50 Etudes Faciles & Progressives, I & II (Guy Lacour) 15 Etudes by J.S. Bach (Caillieret) The Orchestral Saxophonist (Ronkin/Frascotti) Rubank Intermediate and/or Advanced Method (Voxman) Select Solos: Alto Solos for Alto Saxophone (arr. by Larry Teal) Aria (Eugene Bozza) Sicilienne (Pierre Lantier) Dix Figures a Danser (Pierre-Max Dubois) Sonata (Henri Eccles/Rasher) Sonata No. 3 (G.F. Handel/Rascher) Adagio & Allegro (G.F. Handel/Gee) Three Romances, alto or tenor (Robert Schumann) Sonata (Paul Hindemith) 1 A la Francaise (P.M. Dubois) Tenor Solo Album (arr. by Eugene Rousseau) 7 Solos for Tenor Saxophone