ΛΑΒΕ ΤΗΝ ΓΡΑΦΗΝ! Book Format, Authority, and Authorship in Ancient Greek Medical Papyri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletin AHPLP 2 Libro

LOS MEDIOS DE TRANSMISIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN LA EPIGRAFÍA, DE CIENCIA AUXILIAR A CIENCIA HISTÓRICA La Epigrafía, de ciencia auxiliar a ciencia histórica 11 LOS MEDIOS DE TRANSMISIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN MANUEL RAMÍREZ SÁNCHEZ Resumen: La Epigrafía es una ciencia historiográfica indispensable en la formación de los historiadores que, desde hace siglos, forma parte de las mal denominadas “ciencias auxilia- res” de la Historia. En este trabajo se analiza el concepto de Epigrafía, el método epigráfico y el recorrido historiográfico que esta ciencia ha desarrollado a lo largo de la Historia, con el fin de aproximar al lector a los rudimentos de esta ciencia historiográfica, con especial refe- rencia a la labor investigadora que se ha desarrollado en España. El estudio finaliza con un acercamiento a la situación actual de la Epigrafía, no solo en la formación universitaria de las futuras generaciones de historiadores, sino en el análisis de las líneas de investigación y proyectos más importantes que están en curso en la actualidad. Palabras clave: Epigrafía, inscripciones, concepto, método, historiografía. Abstract: Epigraphy is an indispensable science in shaping historiography of historians for centuries, is part of the so-called "auxiliary sciences" of history. In this paper we explore the concept of Epigraphy, the epigraphic method and the historiographical development, to bring the rudiments of this science historiography, with special reference to the work research that has developed in Spain. The study concludes with an approach to the current state of Epigraphy, not only in university education of future generations of historians, but on the analysis of the research and major projects under way today. -

The Antikythera Mechanism, Rhodes, and Epeiros

The Antikythera Mechanism, Rhodes, and Epeiros Paul Iversen Introduction I am particularly honored to be asked to contribute to this Festschrift in honor of James Evans. For the last nine years I have been engaged in studying the Games Dial and the calendar on the Metonic Spiral of the Antikythera Mechanism,1 and in that time I have come to admire James’s willingness to look at all sides of the evidence, and the way in which he conducts his research in an atmosphere of collaborative and curious inquiry combined with mutual respect. It has long been suggested that the Antikythera Mechanism may have been built on the is- land of Rhodes,2 one of the few locations attested in ancient literary sources associated with the production of such celestial devices. This paper will strengthen the thesis of a Rhodian origin for the Mechanism by demonstrating that the as-of-2008-undeciphered set of games in Year 4 on the Games Dial were the Halieia of Rhodes, a relatively minor set of games that were, appro- priately for the Mechanism, in honor of the sun-god, Helios (spelled Halios by the Doric Greeks). This paper will also summarize an argument that the calendar on the Metonic Spiral cannot be that of Syracuse, and that it is, contrary to the assertions of a prominent scholar in Epirote stud- ies, consistent with the Epirote calendar. This, coupled with the appearance of the extremely minor Naan games on the Games Dial, suggests that the Mechanism also had some connection with Epeiros. The Games Dial and the Halieia of Rhodes The application in the fall of 2005 of micro-focus X-ray computed tomography on the 82 surviv- ing fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism led to the exciting discovery and subsequent publi- cation in 2008 of a dial on the Antikythera Mechanism listing various athletic games now known as the Olympiad Dial (but which I will call the Games or Halieiad Dial—more on that below), as well as a hitherto unknown Greek civil calendar on what is now called the Metonic Spiral.3 I begin with my own composite drawing of the Games Dial (Fig. -

CLAS 600 Resources for Research in Greek History and Ancillary Disciplines

CLAS 600 Resources for Research in Greek History and Ancillary Disciplines A comment on early Greek history: “[T]he scantiness of evidence sets a special challenge to the disciplined mind. It is a game with very few pieces, where the skill of the player lies in complicating the rules. The isolated and uneloquent fact must be exhibited within a tissue of hypothesis subtle enough to make it speak….” - Iris Murdoch, The Nice and the Good, Viking Press NY 1968: 176. Literary Sources: The Ancient Texts Selection of Greek (and Roman) Historians Following is a list of the most important historians for the study of Greek history. The list is by no means complete; in general it represents authors whose works survive in whole or in large part, and who are our chief source of evidence for significant periods of Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic history. Herodotos (Halikarnassos). Chief literary source for history of the 6th and early 5th centuries BCE, in particular the Persian Wars; also a significant source of connected narrative of the development of the Persian Empire. Thucydides (Athens). Unfinished. Chief literary source for history of 5th century BCE, from the period immediately after the Persian Wars until 411; specific focus the conflict between Athens and Sparta and their respective spheres of influence (the Peloponnesian War, 431-404 BCE). Xenophon (Athens). Various works, including treatises on hunting and economics, Socratic dialogues, and a largely fictional biography of Cyrus, the first king of Persia. Among his most significant historical writings are the Hellenica, a continuation of Thucydides (Greek history from 411 to 362 BCE), and the Anabasis, an account of a military expedition into the Persian interior at the end of the 5th century, an expedition in which Xenophon himself participated. -

Inscriptiones Graecae Consilio Et Auctor. Acad. Litt. Reg. Boruss. Editae. Vol

NOTICES OF BOOKS 175 Gilioia. By FRANZ X. SCHAFFER. [141st Ergiinzungsheft zu Petermanns Mitteilungen.] Pp. 110. 2 maps, 5 figures. Gotha : Perthes, 1903. 12 m. Dr. Schaffer's exploration of Cilicia during the years 1900 and 1901 was made mainly in the interests of the natural sciences, especially geology. But he did not neglect archaeo- logy altogether, and contributed a paper to the Jahreshefte of the Vienna Arch. Inst. on the route taken by Cyrus' general Menon across Taurus. The substance of this he now includes in his general account of the whole region, and notices briefly other questions of ancient history and topography, e.g. the situation of Mallus and Mopsukrene ; the former navigability of the Cydnus ; and the passes across Taurus. He describes with some fulness the ruins of Tarsus, Anazarba, Elaeousa-Sebaste and Olba, and mentions in passing many minor monuments of the Greek, Roman, and Lesser Armenian periods. Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae. Supplementum Sylloges Inscriptionum Graecarum edidit WILHELMUS DITTENBERGER. Vol. I. Pp. viii.+658. Leipzig: Hirzel, 1903. 18 m. In the Preface to thesecond edition of the indispensable Sylloge, the author promised a supplement containing a selection of Greek inscriptions of the East. The first volume of this Supplement now appears, two years only after the completion of the Sylloge. The book is arranged on the same plan ; the inscriptions themselves are not provided with descriptive titles, but reference is facilitated by headlines giving somewhat more detailed information. It is hardly necessary to speak of the high quality of the work, or to point out how convenient to the historian is the inclusion in one volume of new critical editions of monuments like the Canopus Decree, the Eosetta Stone, the Adule inscription, the Ilian law concerning tyrants, the Smyrna-Magnesia treaty, the dispute between Mytilene and Pitane, the Nemrud-Dagh inscriptions. -

Inscriptions in Byzantium and Beyond Österreichische Akademie Der Wissenschaften Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, 478

ANDREAS RHOBY (ed.) INSCRIPTIONS IN BYZANTIUM AND BEYOND ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE DENKSCHRIFTEN, 478. BAND Inscriptions in Byzantium and Beyond Methods – Projects – Case Studies Edited by ANDREAS RHOBY Vorgelegt von w. M. JOHANNES KODER in der Sitzung vom 24. Oktober 2014 Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 223-G19 Umschlagbild: Orchomenos, church of Skripou, inscription of central apsis (a. 873/74), ed. N. OIKONOMIDÈS, TM 12 (1994) 479–493 © Andreas Rhoby Mit Beschluss der philosophisch-historischen Klasse in der Sitzung vom 23. März 2006 wurde die Reihe Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Byzantinistik in Veröffentlichungen zur Byzanzforschung umbenannt; die bisherige Zählung wird dabei fortgeführt. Diese Publikation wurde einem anonymen, internationalen Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. This publication has undergone the process of anonymous, international peer review. Die verwendeten Papiersorten sind aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff hergestellt, frei von säurebildenden Bestandteilen und alterungsbeständig. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 978-3-7001-7674-9 Copyright © 2015 by Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien Druck und Bindung: Ferdinand Berger & Söhne GmbH., 3580 Horn http://hw.oeaw.ac.at/7674-9 http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at Printed and bound in the EU A NDREAS R HOBY A Short History of Byzantine Epigraphy Abstract: This article offers an overview of the history of the discipline of Byzantine epigraphy from the 19th century until today. It ranges from the description of the first attempts to create corpora of Greek Christian inscriptions at the time of the foundation of modern Byzantine Studies (especially within the French school) to the listing of online editions and other electronic tools. -

Greek Epigraphy – Resources

Greek Epigraphy – Resources The Standard Epigraphic Collections Regional Corpora (a Selection) Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum (CIG). The first attempt at a comprehensive collection of inscriptions from all over the Greek world. Edited by A. Böckh. Berlin 1828-1877. Inscriptiones Graecae (IG). Older but still core series, published originally through the Prussian Academy (Berlin); subsequently through the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy. List of volumes is appended below. Inschriften griechischer Städte aud Kleinasien (IK). Series of volumes dedicated to the publications of inscriptions from sites in Asia Minor. Project still underway. Bonn 1972–. Digests and Thematic Collections (a Selection) Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum (SIG3 or Syll3). Wide selection of a variety of inscriptions (4 volumes). Edited by W. Dittenberger et al. Third edition, Leipzig 1915-1924. Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae (OGIS). Selection of inscriptions from the eastern Greek world. Edited by W. Dittenberger. Leipzig 1903. Inscriptiones Graeci ad res Romanas pertinentes (IGRR). Selection of Greek inscriptions with connections to Rome, Romans, or Roman affairs. Sammlung der griechischen Dialekt-Inschriften (SGDI). Collection of inscriptions illustrating the various Greek dialects. Edited by H. Collitz and F. Bechtel. Göttingen 1884-1915. Royal Correspondence in the Hellenistic Age (RC). C.B. Welles’ collection of texts of royal letters, with translation and commentary. Yale 1934. Athenian Tribute Lists (ATL). Texts and commentary. B.D. Meritt, H.T. Wade-Gery, and M.F. McGregor. Cambridge and Princeton 1939-1953. Meiggs & Lewis (GHI). Russell Meiggs and David Lewis, A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions to the End of the Fifth Century BC. 2nd edition Oxford 1988. Collection of the most significant Archaic and Classical inscriptions, with some translation and extensive scholarly commentary. -

Inscriptiones Graecae Between Present and Future Peter Funke Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Deutschland

e-ISSN 2532-6848 Axon Vol. 3 – Num. 2 – Dicembre 2019 Inscriptiones Graecae Between Present and Future Peter Funke Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Deutschland Abstract In the first part of my ‘workshop report’, I will provide information about the current state of the epigraphical editions of the Inscriptiones Graecae. Subsequently, I will focus on the plans for the upcoming years. In this context, questions pertaining to epigraphic research in new geographic regions, on the one hand, and the revision of past editions, on the other hand, are paramount. In the second part of my report, I will outline the current state and future perspectives of the digitisation of the IG. Keywords Epigraphy. Inscriptiones Graecae. Greek Inscriptions. Cypriot Syllabary. Digital Humanities. In her contribution “L’epigrafia greca tra sienza ed esperienza: il ru- olo di Berolino” at the fifthSeminario Avanzato di Epigrafia Greca in January 2017 in Torino, D. Summa (2017) provided a short review of the historical development of the Inscriptiones Graecae in the last 200 years and an overview of the current state of the ongoing work. On the XVth International Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy in Vi- enna in September 2017, Klaus Hallof (2017) also presented an over- view of the entire opus of the Inscriptiones Graecae. I will be drawing directly upon their talks in my following contribution, without, how- ever, revisiting the overall envisioned publication scheme of the IG. In the first part of ‘my workshop report’, I will briefly outline the current state of the epigraphical editions of the Inscriptiones Graecae. Subsequently, I would like to focus on the plans for the coming years. -

Two Inscribed Documents of the Athenian Empire the Chalkis Decree and the Tribute Reassessment Decree

_________________________________________________________________________ Two Inscribed Documents of the Athenian Empire The Chalkis Decree and the Tribute Reassessment Decree S. D. Lambert AIO Papers no. 8 2017 AIO Papers Published by Attic Inscriptions Online, 97 Elm Road, Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 3DR, United Kingdom. Editor: Dr. S. D. Lambert (Cardiff) Advisory Board: Professor P. J. Rhodes (Durham) Professor J. Blok (Utrecht) Dr. A. P. Matthaiou (Athens) Mr. S. G. Byrne (Melbourne) Dr. P. Liddel (Manchester) © Attic Inscriptions Online 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Attic Inscriptions Online, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Dr. S. D. Lambert at the above address or via the contact given at www.atticinscriptions.com. Front cover: Chalkis decrees, IG I3 40 = Acrop. 6509 © Acropolis Museum (photo: Socratis Mavrommatis). ISSN 2054-6769 (Print) ISSN 2054-6777 (Online) CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................ i Bibliography and Abbreviations ........................................................................................... ii Preface ................................................................................................................................. -

New and Old Panathenaic Victor Lists

NEW AND OLD PANATHENAIC VICTOR LISTS (PLATES71-76) I. THE NEW PANATHENAIC VICTOR LISTS FINDSPOT, DESCRIPTION, AND TEXT The present inscription (pp. 188-189) listing athletic victors in the Panathenaia first came to my attention a number of years ago by word of mouth.1 I do not have accurate information about its initial discovery. The stone was initially under the jurisdiction of Dr. George Dontas, who helped me gain accessto it and determinethat no one was working on it. My own interest in the inscriptionin the first place stemmedfrom the hand. With the assistance of the Greek authorities, especially the two (former) directorsof the Akropolis, G. Dontas and E. Touloupa, whose generous cooperationI gratefully acknowledge,I have been granted permission to publish this important inscription.2In October of 1989 I was able to study the text in situ and also to make a squeeze and photographs.3 I In a joint article it is particularly important to indicate who did what. In this case Stephen Tracy has primary responsibilityfor section I, Christian Habicht for section II, and both authors for IV; section III is subdividedinto parts A, B, and C: Tracy is the primary author of A and B and Habicht of C. Nevertheless, this article is the product of close collaboration.Although initially we worked independently,each of us has read and commentedon the other's work. The final draft representsa version agreed upon by both authors. Photographs:Pls. 71-75, SVT; P1. 76, Tameion ArcheologikonPoron. All dates are B.C., unless otherwise stated. Works frequently cited are abbreviatedas follows: Agora XV = B. -

Epigraphical Index

EPIGRAPHICALINDEX (VOL. 45) PERSONS 'A/3as KXedv8po[v tAu4dv7CvT';], ephebe honored ['EopTt] o0 ('AXapvEvj6),ca. 237/6 a., father of 204/3 a., 29994 ['Ep1.o'8wpos],298 40 'Aya0av8pt'8a(Koptvtow), post ca. 224 a., father 'EpyoXapqp('00ecv), ca. 237/6 a., father of of Ttjoo,fOvv, 253 7 NtKcofovXos, 298 54-55, 64-CS 'AM'tav8pos= Alexander (III), on Macedonian 'EpyoXdp-; NtKoflovlkov O0,v,, ephebe honored coin, 15-16 (2) 204/3 a., 299 85 'AvGo06tveco4wvToS lleptOot'&S,ephebe honored ['Epo'8&opos3 'EOPTL'rfov'AXapv[c]v"-;, paidotribes 204/3 a., 29987 204/3 a., 29840 'Av'rav[8p]o [s] (KoptvOtos), post ca. 224 a., EiKpt'TSE ('E7rtKpptTCtog), ca. 224/3 a., father of father of [-- , 253 6 EVi/KpTo-, 298 84 ['Av]TtOXt8q, honored ca. 420-414 a., 291 EVi/KPtTOSEVxKPt'TOV TEr tatos, ephebe honored (II 3); ['AvTtoX3t7], 291 (II 15-16, 20) 204/3 a., 29984 ['AiroXXO'8wpos],archon 204/3 a., 297 1 'A[pt] crTo[Xs], on coin of Erythrai, 152 (115) Ofo4v (HeptGol'&S), ca. 224/3 a., father of 'ApXqLtaXt'&a;4ka[tow Ko [p(] vOtos,post 191 a., 'AvOcEwv,299 87 dikast on Eleian decree found at Corinth, [E)paJrov] ('09ev), ca. 237/6 a., father of 253 6 [---3, f297 2 'ApxeuaxosHIEaLGaw Ko [pt]vGtoL post 191 a., ca. 224/3 father of dikast on Eleian decree found at Corinth, K tcrO4wV( iovAOpvEs), a., 253 8 AvaxZvos, 299 91 KXeavapo[3] (tAjua$avTre), ca. 224/3 a., father #Arra,kos (BCpfVtKt8q), ca. 140/39 a., father of of 299 94 [- ] a'8-q,287 (3 2) "Aflas, KlOv&v5Evo6vTro [v KELptau,3s, ephebe honored 204/3 a., 299 93 Aa,[--- -. -

From Smyrna to Stewartstown: a Numismatist's

3 FROM SMYRNA TO STEWARTSTOWN: A NUMISMATIST'S EPIGRAPHIC NOTEBOOK By DAVID WHITEHEAD, MRIA School of Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast wReceived 22 May 1998. Read 1 October 1998. Published 23 December 1999x ABSTRACT The paper concerns an anonymous nineteenth-century notebookᎏ currently in Northern Irelandᎏ containing transcripts of over two hundred ancient Greek and other inscriptions from the eastern Mediterranean. An appendix to the paper catalogues these contents and contextualises them in modern bibliography. In sections 1᎐4 the book's original ownerrcompiler is shown, by internal and external evidence, to have been Henry Perigal BorrellŽ. 1795᎐1851 , best known as an amateur scholar of numismatics and a supplier of coins via the Bank of England to the British Museum. Sections 5᎐9 then ask how the book travelled from Borrell's home in SmyrnaŽ. Izmir to Stewartstown, County Tyrone. The key figure in that journey is identified as James Kennedy Bailie, MRIAŽ. 1793᎐1864 , rector of Ardtrea, County Tyrone, who repaid Borrell's generosity in sending him the book by plagiaristically publishing many of its items. After Bailie the line of transmission was through one of the prominent Huguenot families of the area. Introduction I present here the results of my study of a manuscript notebook written by an accomplished amateur antiquarian who was activeŽ. as will be seen in the Aegean and the Levant during the second quarter of the nineteenth century.1 The book's present owner is Mr James Glendinning of Stewartstown, County Tyrone, who deposited it for scrutiny at the Ulster Museum in Belfast in July 1997. -

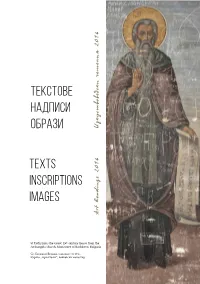

Текстове Надписи Образи Texts Inscriptions Images

ТЕКСТОВЕ НАДПИСИ ОБРАЗИ Изкуствоведски четения 2016 TEXTS INSCRIPTIONS IMAGES Art Readings 2016 St Euthymius the Great, 19th century fresco from the Archangels church, Monastery of Bachkovo, Bulgaria Св. Евтимий Велики, стенопис от 19 в., църква „Архангели“, Бачковски манастир ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома ART READINGS Thematic annual peer-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes Международна редакционна колегия International Advisory Board Andrea Babuin (Italy) Konstantinos Giakoumis (Albania) Nenad Makulijevic (Serbia) Vincent Debiais (France) Редактори от ИИИзк In-house Editorial Board Ivanka Gergova Emmanuel Moutafov Научни редактори на тома Scholarly Edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan (Serbia) Institute of Art Studies 21 Krakra Str. 1504 Sofia Bulgaria www.artstudies.bg © Институт за изследване на изкуствата, БАН, 2017 ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома 2016/ т. I – Старо изкуство ТЕКСТОВЕ • НАДПИСИ • ОБРАЗИ TEXTS • INSCRIPTIONS •IMAGES ART READINGS Thematic annual peеr-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes 2016/ vol. I – Old Art Под научната редакция на Емануел Мутафов Йелена Ерделян Scholarly edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan София 2017 Книгата се издава със съдействието на Плесио компютърс Content Art Readings 2016 ............................................................................................................11 Emmanuel Moutafov The Visual Language of Roman Art and Roman