Source Water Protection Planning for Ontario First Nations Communities: Case Studies Identifying Challenges and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Management Plan 2016

Interim Management Plan 2016 JANUARY 2016 Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area of Canada Interim Management Plan ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2016. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data: Parks Canada LAKE SUPERIOR NATIONAL MARINE CONSERVATION AREA INTERIM MANAGEMENT PLAN Issued also in French under the title: PLAN DIRECTEUR PROVISOIRE DE L’AIRE MARINE NATIONALE DE CONSERVATION DU LAC-SUPÉRIEUR Available also on the Internet. ISBN: R64-344-2015E Cat. no. 978-0-660-03581-9 For more information about the interim management plan or about Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area of Canada Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area of Canada 22 Third Street P.O. Box 998 Nipigon, Ontario, Canada P0T 2J0 Tel: 807-887-5467, fax: 807-887-5464 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/amnc-nmca/on/super/index.aspx Front cover image credits top from left to right: Rob Stimpson, Dale Wilson and Dale Wilson bottom: Dale Wilson Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area of Canada iii Interim Management Plan iv vi Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area of Canada vii Interim Management Plan Interim Management Advisory Board Members Township of Terrace Bay – Jody Davis (Chair) Township of Red Rock - Kal Pristanski (Previous Chair) Community of Rossport – Lorne Molinski Fort William First Nation – Tina Morriseau Lakehead University – Harvey Lemelin Member at Large – Dave Nuttall Member at Large – Paul Capon Member at Large – Vacant Seat Northern Superior First Nations – Peter Collins (Regional Chief) Pays Plat First Nation - Chief Xavier Thompson (Alternate – Raymond Goodchild) Red Rock Indian Band – Ed Wawia Remote Property Owners – Vacant Seat Silver Islet Campers’ Association – Scott Atkinson (Kevin Kennedy – deceased, 2011) Superior North Power & Sail Squadron – Bill Roen Thunder Bay Field Naturalists – Jean Hall-Armstrong Thunder Bay Yacht Club – Rene St. -

Here Is a Copy of Correspondence with Manitouwadge From: Edo

From: Tabatha LeBlanc To: Cathryn Moffett Subject: Manitouwadge group - letter of support Date: March 17, 2021 11:34:41 AM Attachments: <email address removed> Here is a copy of correspondence with Manitouwadge From: [email protected] <email address removed> Sent: October 28, 2020 11:00 AM To: Tabatha LeBlanc <email address removed> Cc: Owen Cranney <email address removed> ; Joleen Keough <email address removed> Subject: RE: PGM Hi Tabatha, This email is to confirm that the Township would be happy to host Generation Mining via Zoom for a 15 minute presentation to Council at 7:00 pm on Wednesday, November 11, 2020. The format will be 15 min for presentation and 10 min for Q&A. Can you please forward your presentation no later than Wednesday, November 4th to circulate to Council with their Agenda package. We will also promote the presentation online for members of the public to watch the live stream of the video through our YouTube channel. Member of the public may have questions or comments on the project so we will need to ensure that they know how and who to contact at Generation Mining. Please advise the names and positions of anyone from Generation Mining who will be present for the presentation. Please log in to the Zoom link a few minutes before 7 pm. You will be placed in a “waiting room” and staff will admit you prior to the meeting start time at 7:00 pm. Let me know if you have any questions. Thanks, Florence The Zoom meeting link is attached below: Township of Manitouwadge is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. -

Voices from the Indigenous Midwifery Summit

Bring Birth Home! Voices from the Indigenous Midwifery Summit: A Reclamation of Community Birth Through a Northern Indigenous Vision We acknowledge the lands, waters and air of our meeting are kin to the Anishinaabeg since time before time. The Indigenous Midwifery Summit was held on the lands of the Fort William First Nation and what is now known as the Robinson Superior Treaty, which led to the formation of the City of Thunder Bay. We offer our most sincere gratitude to our northern Fort William First Nation kin in the spirit of positive, reciprocal and long-lasting relationship-building. We celebrate the diversity of gender expression and identities. The traditional use of the term “motherhood” and “woman” at times in this document includes ALL women, including trans women, two spirit people, and non-binary people. Indigenous Midwifery Summit Fort William First Nation, Robinson Superior Treaty Thunder Bay, ON February 12 and 13, 2019 “I do it for the community. I do it for the women… it is wonderful having beautiful births, having them here, having the mothers have confidence in me, in us, and the whole team.” Midwifery student from Nunavik Event organizer and host: · 2 · 04 Executive Summary: Gathering the Circle 06 Thank You to All Our Supporters 08 What is an Indigenous Midwife? 10 Overview 12 Indigenous Midwifery Summit Agenda Making Connections 13 Preconference Reception 14 Day 1 Summary 15 Day 2 Summary What We Heard: Summit Themes 17 Central Theme: Bring Birth Home 18 Subtheme 1: Centre Indigeneity and Self-Determination 19 -

March 2005 in the NEWS Federal Budget Only Funding WANTED Two First Nation Houses Per Year Anishinabek Writers by Jamie Monastyrski Ence About Aboriginal Issues

Volume 17 Issue 2 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 March 2005 IN THE NEWS Federal budget only funding WANTED two First Nation houses per year Anishinabek Writers By Jamie Monastyrski ence about aboriginal issues. One (Files from Wire Services) spoke about shameful conditions. NIPISSING FN — First Well, if there’s an acceptance and a Nations across Canada are disap- recognition that indeed conditions pointed with the 2005 Federal are shameful, well, what are we budget, especially with the alloca- going to do about those shameful tion to address a growing housing conditions?” crisis. Although there was a definite “With this budget, the sense of disappointment from First Put your community on Government of Canada has done Nations over housing and residen- the map with stories and little to improve housing condi- tial school programs, the Union of photos. Earn money too. tions on First Nations,” said Ontario Indians expressed opti- Contact Maurice Switzer, Editor Anishinabek Nation Grand mism over the government’s com- Telephone: (705) 497-9127 Council Chief John Beaucage, not- mitment towards youth and family Toll Free: 1-877-702-5200 ing that the budget translates into social programs and their attempt [email protected] two new houses a year for each of to meet the needs and addressing the 633 First Nations for five years. the priorities of First Nations com- FN Gaming guru “This announcement isn’t even Anishinabek Nation Grand Council Chief John Beaucage chats with munities. close to what is needed to improve actress and National Aboriginal Achievement Award winner Tina Keeper. -

How to Apply

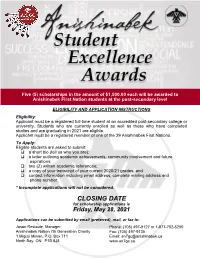

Five (5) scholarships in the amount of $1,500.00 each will be awarded to Anishinabek First Nation students at the post-secondary level ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS Eligibility: Applicant must be a registered full-time student at an accredited post-secondary college or university. Students who are currently enrolled as well as those who have completed studies and are graduating in 2021 are eligible. Applicant must be a registered member of one of the 39 Anishinabek First Nations. To Apply: Eligible students are asked to submit: a short bio (tell us who you are); a letter outlining academic achievements, community involvement and future aspirations; two (2) written academic references; a copy of your transcript of your current 2020/21 grades; and contact information including email address, complete mailing address and phone number. * Incomplete applications will not be considered. CLOSING DATE for scholarship applications is Friday, May 28, 2021 Applications can be submitted by email (preferred), mail, or fax to: Jason Restoule, Manager Phone: (705) 497-9127 or 1-877-702-5200 Anishinabek Nation 7th Generation Charity Fax: (705) 497-9135 1 Migizii Miikan, P.O. Box 711 Email: [email protected] North Bay, ON P1B 8J8 www.an7gc.ca Post-secondary students registered with the following Anishinabek First Nation communities are eligible to apply Aamjiwnaang First Nation Moose Deer Point Alderville First Nation Munsee-Delaware Nation Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Namaygoosisagagun First Nation Aundeck Omni Kaning Nipissing First Nation -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7 -

Mining Essentials Program

Entrance Requirements Mining Essentials & Anishinabek 17 years of age or older Underground Hard Rock Employment and Self identified as Aboriginal Common Core Training Completed Grade 12 or GED Equivalent Program Contacts: Training Services Be referred into the program through pre- assessment activities (Applicants should John DeGiacomo, be prepared to explain, why they are inter- AETS Proposal & Partnership ested in a career in mining as well as com- Development Officer plete an application process including a free Test of Workplace Essential Skills Assessment (TOWES). If requested, ap- Vernon Ogima, plicants must participate in an interview AETS Project Co-ordinator covering the following topics to manage barriers for success: Housing, Training Riley Burton, Location, Health, Travel, Funding, Educa- Confederation College Mining Essentials & tional levels, Language, Environment.) ———————————————- Underground Hard Rock How to Apply AETS is in the process of collecting appli- Common Core Training Anishinabek Employment cations on behalf of applicants who have Program for Aboriginal First Nation Affiliation with the eight First and Training Services Nation Communities served by AETS. 277 Park Avenue People - 2011/2012 Please call 866-870-2387 toll free for Thunder Bay, Ontario, P7B 1C4 more information, or fax the following Tel.: (807) 346-0307 completed documents to 807-346-0310 by Fax: (807) 346-0310 Wednesday February 1, 2012 at 12:00 Toll Free: 866-870-AETS (2387) Noon: Application and Consent Form (via Email: [email protected] http://www.aets.org/application.pdf) Resume Website: www.aets.org Ontario Ministry of Training, 3 Character References and an Colleges and Universities Academic Transcript(s) Our Mission APPLICATION PROCESS First Nation Partners: To assist in the development of a skilled Information Sessions - Starting Week Animbiigoo Zaagi'igan Anishinaabek Aboriginal workforce through the provi- of January 16th, 2012 (Lake Nipigon Ojibway) sion of individual and community based Application Deadline - Feb. -

Akisq'nuk First Nation Registered 2018-04

?Akisq'nuk First Nation Registered 2018-04-06 Windermere British Columbia ?Esdilagh First Nation Registered 2017-11-17 Quesnel British Columbia Aamjiwnaang First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Sarnia Ontario Abegweit First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Scotchfort Prince Edward Island Acadia Registered 2012-12-18 Yarmouth Nova Scotia Acho Dene Koe First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Fort Liard Northwest Territories Ahousaht Registered 2016-03-10 Ahousaht British Columbia Albany Registered 2017-01-31 Fort Albany Ontario Alderville First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Roseneath Ontario Alexis Creek Registered 2016-06-03 Chilanko Forks British Columbia Algoma District School Board Registered 2015-09-11 Sault Ste. Marie Ontario Animakee Wa Zhing #37 Registered 2016-04-22 Kenora Ontario Animbiigoo Zaagi'igan Anishinaabek Registered 2017-03-02 Beardmore Ontario Anishinabe of Wauzhushk Onigum Registered 2016-01-22 Kenora Ontario Annapolis Valley Registered 2016-07-06 Cambridge Station 32 Nova Scotia Antelope Lake Regional Park Authority Registered 2012-01-01 Gull Lake Saskatchewan Aroland Registered 2017-03-02 Thunder Bay Ontario Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Registered 2017-08-17 Fort Chipewyan Alberta Attawapiskat First Nation Registered 2019-05-09 Attawapiskat Ontario Atton's Lake Regional Park Authority Registered 2013-09-30 Saskatoon Saskatchewan Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority Registered 2012-01-01 Exeter Ontario Barren Lands Registered 2012-01-01 Brochet Manitoba Barrows Community Council Registered 2015-11-03 Barrows Manitoba Bear -

Lake Superior Study Area’S Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community

Historical Profile of the Lake Superior Study Area’s Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community FINAL REPORT PREPARED BY FOR THE OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL INTERLOCUTOR SEPTEMBER 2007 Lake SuperiorMixed Ancestry Final Report Historical Profile of the Lake Superior Study Area’s Mixed European-Indian Ancestry Community TABLE OF CONTENTS Map: The proposed Lake Superior NMCA 3 Executive Summary 4 Methodology/Introduction 5 Comments on Terminology 6 Chapter 1: Study Region from the 17th Century to the 1840s 8 Ojibway Indians residing on the North Shore of Lake Superior 8 Europeans and the Study Area 9 Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 12 Mention of Mixed-Ancestry people in the Study Region 15 Chapter 2: Aboriginal Pressure for a Treaty Relationship 25 Louis Agassiz and the Study Region, 1848 28 Treaty Exploratory Commission 28 Mica Bay, 1849 33 Vidal and Anderson Report 35 Government Instructions about Treaty Terms 37 Robinson Travels to Sault Ste. Marie 38 Request for Recognition of “Halfbreed” rights 40 Negotiation of the Robinson-Superior Treaty 40 Chapter 3: Post-Treaty Government Activity 44 “Halfbreed” inclusion in Robinson-Superior Treaty Annuity Paylists 44 Postal Service in the Study Region 46 Crown Activity between 1853 and 1867 46 Chapter 4: Settlement, Resource Development, and Government Administration within the Study Region, 1864-1901 51 Policing 53 Post Office and Railroad 55 Census Information and the Study Region 58 1871, 1881, and 1891 Censuses – Nipigon 59 1881 Census – Silver Islet 61 1901 Census – Nipigon Township (including Dorion), Rossport (including Pays Plat), and Schreiber 62 Small townships not included in early Censuses 63 Joan Holmes and Associates, Inc. -

For a List of All Advisors Please Click Here

Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility Regional Services and Corporate Support Branch – Contact List Region and Office Staff Member Program Delivery Area Central Region Laura Lee Dam Not Applicable Toronto Office Manager 400 University Avenue, 2nd Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (519) 741-7785 Central Region Roya Gabriele Not Applicable Toronto Office Regional Coordinator 400 University Avenue, 2nd Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 631-8951 Central Region Sherry Gupta Not Applicable Toronto Office Public Affairs and Program 400 University Avenue, 2nd Coordinator Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 620-6348 Central Region Irina Khvashchevskaya Toronto West (west of Bathurst Street, north to Steeles Toronto Office Regional Development Advisor Avenue) and Etobicoke 400 University Avenue, 2nd Sport/Recreation, Culture/Heritage, Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Seniors and Accessibility Portfolios Email: [email protected] Phone: (647) 629-4498 Central Region, Bilingual Mohamed Bekkal Toronto East (east of Don Valley Parkway, north to Steeles Toronto Office Regional Development Advisor Avenue) and Scarborough 400 University Avenue, 2nd Sport/Recreation, Culture/Heritage, Floor Toronto, Ontario M7A 2R9 Seniors and Accessibility Portfolios Francophone Organizations in Toronto Email: [email protected] Phone: (416) 509-5461 Central Region Shannon Todd -

Weekly Newsletter for April 5-11 Flyers Are to Be Delivered Each Weekend by 4Pm Sunday Evening

Weekly Newsletter for April 5-11 Flyers are to be delivered each weekend by 4pm Sunday evening. Didn’t receive your newsletter this weekend? Please call Kristy Boucher at 623-9543 ext.217 or [email protected] with your questions or concerns. Finance Information Page For: • Direct Deposit Forms for Member Distributions • Youth Turning 18 – Direct Deposit Forms • Late Banking Information – Annual Member Distributions • Are You Making a Payment? Is now on Page 2 of our Weekly Newsletter Stay informed, follow us on: @fortwilliamfirstnation @FWFN1 NOTICE TO ON RESERVE HOUSEHOLDS WITH DOGS Letting your dog run loose, puts them and the community members in danger. It is up to the pet owner to control their pets, and protect others from them. Pet owners can be held accountable if their pet hurts someone. Please be advised that Flyer Carriers have the right to refuse delivery to the household in they encounter a dog or dogs in the area that makes them feel unsafe. Finance Christmas Boundary Interest Distribution Further to the November 25, 2020 Chief and Council meeting your December 4, 2020 distribution details are as follows: $500 per adult (aged 18 and older) member from the Boundary Trust Income Allocation $35 per adult (aged 18 and older) member from the Boundary Trust Income Allocation $50 for Elders aged 55-plus (at December 31, 2020) from the OFNLP funds The above will be paid by EFT (electron funds transfer) and was uploaded to the RBC on Friday December 4, 2020. Funds may take up to 5-days to be deposited in your account so if you have not received your funds by Friday December 11, 2020 then please contact us at that time.