Collective Identity of Native Social Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

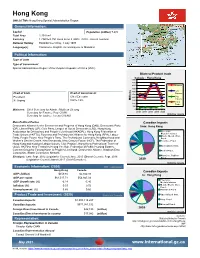

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement

! ! ! ! ! 2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement A report of the State Violence Database Project in Hong Kong Compiled by The Professional Commons and Hong Kong In-Media ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! About!us! ! About!the!research! ! Maps!/!Glossary! ! Executive!Summary! ! 1.! Report!on!physical!injury!and!mental!trauma!...........................................................................................!13! 1.1! Physical!injury!....................................................................................................................................!13! 1.1.1! Injury!caused!by!police’s!direct!smacking,!beating!and!disperse!actions!..................................!14! 1.1.2! Excessive!use!of!force!during!the!arrest!process!.......................................................................!24! 1.1.3! Connivance!at!violence,!causing!injury!to!many!.......................................................................!28! 1.1.4! Delay!of!rescue!and!assault!on!medical!volunteers!..................................................................!33! 1.1.5! Police’s!use!of!violence!or!connivance!at!violence!against!journalists!......................................!35! 1.2! Psychological!trauma!.........................................................................................................................!39! 1.2.1! Psychological!trauma!caused!by!use!of!tear!gas!by!the!police!..................................................!39! 1.2.2! Psychological!trauma!resulting!from!violence!...........................................................................!41! -

The Professional Commons Preliminary Response To

LC Paper No. CB(2)2698/06-07(04) THE PROFESSIONAL COMMONS PRELIMINARY RESPONSE TO THE GOVERNMENT’S GREEN PAPER ON CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 10 SEPTEMBER 2007 A. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1. The Government has released its Green Paper on Constitutional Development (the “Green Paper”) in July 2007. It is seeking submissions from the public on the issues raised in the paper, which deals with the future electoral arrangements for the post of the Chief Executive (“CE”) and for the Legislative Council (“LegCo”). 2. This paper sets out our position in relation to the proposals set out in the Green Paper. Although the Green Paper has set out a number of specific questions to which the Government invites response, we will not deal with the issues in accordance with those questions. This is because the questions appear to reduce the whole consultation process to a “box ticking” exercise, whereby respondents are expected no more than to be a “statistic” on specific mechanisms, rather than providing opportunities for dealing with similarly important issues of principle. 3. Against this background, this paper will be divided into the following sections: 3.1. “Universal suffrage – what is it?”; 3.2. “Universal suffrage – Hong Kong is ready”; 3.3. “Models for CE elections by universal suffrage”; 3.4. “Models for LegCo elections by universal suffrage”; and 3.5. “Hong Kong: it’s time”. 4. In dealing with these issues, we have deliberately not taken a highly technical, legalistic approach. We believe that whilst, as professionals, we must not avoid altogether the technical questions in our analysis, Hong Kong’s political system does not belong only to businessmen, professionals and other alleged “elites”. -

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03)

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03) 25th May 2018 Legislative Council Complex 1 Legislative Council Road Central, Hong Kong Dear Members of Legislative Council, Public Hearing on May 28th 2018: Review of relevant provisions under Cap. 586 We write to express our continued support for the Hong Kong Government's commitment to protecting and conserving wildlife, under the Protection of Endangered Species Ordinance (Cap. 586). We are grateful for the government’s recent amendments to Cap. 586, implementing the three-step plan to ban the Hong Kong ivory trade and the increase in maximum penalties under Cap 586. However, there remain challenges for the regulation of wildlife trade in Hong Kong and in tackling wildlife crime, which we suggest addressing through legalisation. The challenges, as we see them, include: The vast scale of the legal trade in shark fins: - In 2017, Hong Kong imported approximately 5,000 metric tonnes (MT) of shark fins1. - Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), species traded for the seafood and TCM industries, including shark fins, sea cucumber and seahorses, dominated wildlife imports by volume between 2007 to 2016 (87%). - This is all the more concerning, as a recent paper2 revealed that nearly one-third of the species currently identified within the trade in Hong Kong are considered ‘Threatened’ by the IUCN. An illegal trade in shark fins also thrives in Hong Kong: - Out of the 12 endangered shark species internationally protected under CITES regulations, five are known to have been seized as they were trafficked to Hong Kong over the last five years. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/CA LC Paper No. CB(2)133/12-13 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of special meeting held on Saturday, 19 May 2012, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Dr Hon Margaret NG Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon LEE Wing-tat Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, BBS, JP Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, JP Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Dr Hon Samson TAM Wai-ho, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Members : Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH absent Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC - 2 - Hon CHIM Pui-chung Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon WONG Yuk-man Public Officers : Sessions One to Three attending Office of the Chief Executive-elect Mrs Fanny LAW FAN Chiu-fun Head of the Chief Executive-elect's Office Ms Alice LAU Yim Secretary-General of the Chief Executive-elect's Office Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau Mr -

Chapter 18: Crowdfunding and Its Regulation in Hong Kong: Room for Inertia?

351 CHAPTER 18 CROWDFUNDING AND ITS REGULATION IN HONG KONG: ROOM FOR INERTIA? Lareina J Chan* I INTRODUCTION The pace at which technology is developing and revolutionising the way we do things accelerates exponentially. With the blink of an eye, the world is presented with further technological advances that make what we thought was revolutionary yesterday, no longer so revolutionary. "Traditional" businessmen, policymakers, regulators and other stakeholders struggle to keep up to pace, and it is difficult to jump onto the bandwagon when it is difficult to find a suitable place take the leap. From a broader perspective, disruptive technologies – like the Internet was and is – transform the way we live and work, enable new business models, and provide an opening for new players to upset and disrupt the established order. 1 Policymakers need to prepare for future technology, equipped with a clear understanding of how such technology may shape the global economy and society over the coming decade.2 Governments need to create an environment in which citizens can continue to prosper, even as emerging technologies "disrupt" their lives.3 Regulators will be challenged and pressured to achieve the fine balance of protecting the rights and privacy of citizens, while providing room for such an ecosystem promoting upward societal growth. It will be too late for businesses, policymakers and citizens to plan their responses only after disruptive technologies have fully exerted their influence on * Barrister-At-Law, Garden Chambers, Hong Kong. 1 See McKinsey Global Institute (May 2013), Preface. 2 Ibid at p 1. 3 Ibid. 352 HARMONISING TRADE LAW the economy and society as a whole. -

The 2017 Election Reforms (Update)

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2017 Election Reforms (Update) (name redacted) Specialist in Asian Affairs July 1, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44031 Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2017 Election Reforms (Update) Summary The United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-383) declares that, “Support for democratization is a fundamental principle of U.S. foreign policy. As such, it naturally applies to United States policy toward Hong Kong.” China’s law establishing the Hong Kong Special Administration Region (HKSAR), commonly referred to as the “Basic Law,” declares that “the ultimate aim” is the selection of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive (CE) and Legislative Council (Legco) by universal suffrage. The year 2015 may be a pivotal year for making progress toward the objectives of both of these laws. It could also be a year in which the democratic aspirations of many Hong Kong residents remain unfulfilled. Hong Kong’s current Chief Executive, Leung Chun-ying, initiated a six-step process in July 2014 whereby Hong Kong’s Basic Law could be amended to allow the selection of the Chief Executive by universal suffrage in 2017. On August 31, 2014, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) completed the second step of the reform process when it issued a decision setting comparatively strict conditions on the adoption of universal suffrage for the 2017 CE elections that seemingly preclude the nomination of a pro-democracy candidate. The third step of the process, the CE submitting legislation to Legco to amend the Basic Law, came on June 17. -

Public Consultation on the Draft Urban Renewal Strategy Summary Of

Public Consultation on the Draft Urban Renewal Strategy Summary of Public Views and Responses Development Bureau February 2011 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Summary of Public Views and Responses Page 1. Objectives, Principles and Approach of the Urban Renewal Startegy 1 2. District Urban Renewal Forum 5 3. The Role of the Urban Renwal Authority 14 (a) Accountability, Transparency and Financial Arrangements 14 (b) Redevelopment – The Role of an Implementer 21 (c) Redevelopment – The Role of a Facilitator 28 (d) Rehabilitation 33 (e) Heritage Preservation 40 4. Land Assembly Process in URA-implemented Redevelopment Projects 42 (a) Resumption of Land under the Law 42 (b) Compensation to Owners of Domestic Units 43 (i) Compensation and Ex gratia Payment 43 (ii) “Flat for Flat” 49 (c) Assistance to Shop Operators and Shop Owners 55 5. Processing of URA-implemented Redevelopment Projects 59 (a) Planning Procedures 59 (b) Freezing Surveys 60 (c) Social Impact Assessments 64 6. Urban Renewal Trust Fund 66 7. Others 73 (a) Public Consultation on URS Review 73 (b) Comments on Amendments to the Text of the URS 75 (c) Specific Topics and Comments on Cases 78 Annex I: List of Written Submissions 1. Introduction Section 20 of the Urban Renewal Authority Ordinance (Chapter 563) requires the Secertary for Development to consult the public before finalising the urban renewal strategy. In line with the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government’s emphasis on public engagement in recent years, the Development Bureau carried out an extensive 3-stage public consultation between July 2008 and June 2010 to review the strategy, during which over 2,400 public opinions/comments were received. -

How Colonial Legacies in Hong Kong Shape Street Vendor and Public Space Policies

The Blame Game: How colonial legacies in Hong Kong shape street vendor and public space policies By Andrea Kyna Chiu-wai Cheng A.B. Economics Bryn Mawr College (1993) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 © 2012 Andrea Cheng. All Rights ReserVed The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author_______________________________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2012 Certified by _________________________________________________________________________________________ Associate Professor Annette Kim Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis SuperVisor Accepted by__________________________________________________________________________________________ Professor Alan Berger Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning 1 2 The Blame Game: How colonial legacies in Hong Kong shape street vendor and public space policies By Andrea Kyna Chiu-wai Cheng Abstract Hong Kong has seen seVeral social moVements emerge since 2003 that haVe focused on saVing quotidian public spaces, such as traditional shopping streets and markets, from redeVelopment. This thesis explores how the most important form of public space in Hong Kong, streets and sidewalks, has been shaped by the regulatory framework for street vendors and markets, which in turn bears the imprint of Hong Kong’s colonial heritage. I seek to identify contradictions between the ways society currently uses space and the original intent of the regulations, and establish if these can explain current frictions over public space expressed as protests. -

The Hong Kong SAR Government Received a Tremendous Amount Of

“Fairness, Forward-looking, Development” Research Report on “Better Use of Fiscal Surplus” The Professional Commons January 2008 1 “Fairness, Forward-looking, Development” Research Report on “Better Use of Fiscal Surplus” The Professional Commons I. Background Budget Surplus 1. In line with the upward economic trend in recent years, the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (hereafter the Government) has recorded a tremendous fiscal surplus. In the fiscal years 2004-05 and 2005-06, the Government recorded a total consolidated surplus of HK$35.3 billion.1 In the fiscal year of 2006-2007, the Government recorded an astonishing fiscal surplus of HK$124.9 billion, the figure being calculated on the more accurate ―accrual basis‖.2 The trend of fiscal surplus is likely to continue in this fiscal year, as the Hong Kong Taxation Society and the accountancy firm PriceWaterhouseCoopers, for example, have anticipated that this year‘s budget surplus will exceed HK$100 billion, much higher than surplus of HK$25.4 billion projected by the Government.3 Feedback to Last Year’s Concessionary Measures 2. In the 2007-08 Budget, a number of measures were put forward by the Financial Secretary to ―return wealth to the people‖, including: Suspending the collection of rates for a total of two quarters; Waiving 50 per cent of salaries tax and tax under personal assessment; Widening of the band width of the salaries tax and reducing the two highest marginal tax rates; 1 The ―Total Government Revenue and Expenditure and Summary of Financial Position,‖ tables in the Hong Kong Yearbook 2005 and 2006, <http://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2005/en/app_06_06.htm>, <http://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2006/en/app_06_06.htm>. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/CA LC Paper No. CB(2)943/07-08 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of special meeting held on Wednesday, 12 September 2007, at 9:00 am in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) present Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Margaret NG Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Yiu-chung Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum, JP Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Hon LEE Wing-tat Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Hon WONG Ting-kwong, BBS Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Member : Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, SBS, JP Attending - 2 - Members : Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, SBS, JP (Chairman) absent Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon CHAN Yuen-han, SBS, JP Hon Bernard CHAN, GBS, JP Hon Howard YOUNG, SBS, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, BBS, JP Hon Daniel LAM Wai-keung, SBS, JP Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, SBS, JP Hon CHIM Pui-chung Prof Hon Patrick LAU Sau-shing, SBS, JP Hon KWONG Chi-kin Public Officers : Item II attending The Administration Mr Stephen LAM Sui-lung Secretary -

Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

1 VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau Hong Kong During the Commission’s 2016 reporting year, the growing influ- ence of the Chinese central government and Communist Party and suspected activity by Chinese authorities in Hong Kong—notably the disappearance, alleged abduction, and detention in mainland China of five Hong Kong booksellers—raised fears regarding Hong Kong’s autonomy within China as guaranteed under the ‘‘one coun- try, two systems’’ policy enshrined in the Basic Law, which pro- hibits mainland Chinese authorities from interfering in Hong Kong’s internal affairs.1 Tensions over the Chinese government’s role in Hong Kong and the future of Hong Kong’s political system contributed to the growth of ‘‘localist’’ 2 political sentiment, with candidates seen as localist or supportive of self-determination for Hong Kong winning seats in Hong Kong’s September 2016 Legisla- tive Council elections. UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM Hong Kong’s Basic Law guarantees freedom of speech, religion, and assembly; promises Hong Kong a ‘‘high degree of autonomy’’; prohibits Chinese authorities from interfering in Hong Kong’s in- ternal affairs; and affirms that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) applies to Hong Kong.3 The Basic Law also states that its ‘‘ultimate aim’’ is the election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and Legislative Council (LegCo) ‘‘by uni- versal suffrage.’’ 4 Forty out of 70 LegCo members are elected di- rectly by voters and 30 by functional constituencies,5 which are composed of trade