How Colonial Legacies in Hong Kong Shape Street Vendor and Public Space Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

Building an Unjust Foodscape: Shifting Governance Regimes, Urban Place Making and the Making of Chinese Food As Ordinary in Hong Kong

This is a repository copy of Building an Unjust Foodscape: Shifting Governance Regimes, Urban Place Making and the Making of Chinese Food as Ordinary in Hong Kong. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/115978/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Blake, M.K. orcid.org/0000-0002-8487-8202 (2017) Building an Unjust Foodscape: Shifting Governance Regimes, Urban Place Making and the Making of Chinese Food as Ordinary in Hong Kong. Local Environment. ISSN 1354-9839 https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1328674 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Building an Unjust Foodscape: Shifting Governance Regimes, Urban Place Making and the Making of Chinese Food as Ordinary in Hong Kong Food Justice Special Issue Megan K Blake Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 2TN UK [email protected] This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Local Environment. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

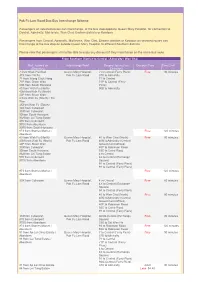

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme Passengers on selected routes can interchange, at the bus stop opposite Queen Mary Hospital, for connection to Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon. Passengers from Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon on selected routes can interchange at the bus stop on outside Queen Mary Hospital, to different Southern districts. Please note that passengers will not be able to enjoy any discount if they interchange on the same bus route. From Southern District to Central / Admiralty / Wan Chai First Journey on Interchange Point Second Journey on Discount Fare Time Limit (Direction) (Direction) 7 from Shek Pai Wan Queen Mary Hospital, 7 to Central (Ferry Piers) Free 90 minutes 37X from Chi Fu Pok Fu Lam Road 37X to Admiralty 71 from Wong Chuk Hang 71 to Central 71P from Sham Wan 71P to Central (Ferry 90B from South Horizons Piers) 40 from Wah Fu (North) 90B to Admiralty 40M fromWah Fu (North) 40P from Sham Wan 4 from Wah Fu (South) / Tin Wan 4Xfrom Wah Fu (South) 30X from Cyberport 33Xfrom Cyberport 93from South Horizons 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate 970 from Cyberport 970X from Aberdeen X970 from South Horizons 973 from Stanley Market / Free 120 minutes Aberdeen 40 from Wah Fu (North) Queen Mary Hospital, 40 to Wan Chai (North) Free 90 minutes 40M from Wah Fu (North) Pok Fu Lam Road 40M toAdmiralty (Central 40P from Sham Wan Government Offices) 33X from Cyberport 40P to Robinson Road 93from South Horizons 93C to Caine Road 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate -

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal Sponsoring Agencies: Designing Hong Kong and Harbour Business Forum Submitted to: Project Advisor: Zhikun Hou, WPI Professor Project Co‐advisor: Robert Kinicki, WPI Professor On‐Site Liaison: Paul Zimmerman, Designing Hong Kong On‐Site Co‐Liaison: Dr. Sujata S. Govada, Harbour Business Forum Submitted by: Michael Audi Kathryn Byorkman Alison Couture Suzanne Najem Date Submitted: 15 December 2010 Creighton Peet ID 2050 Instructor Table of Contents Title Page .............................................................................................................................................. i Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. ii Table of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iv Table of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background .................................................................................................................................... 4 -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

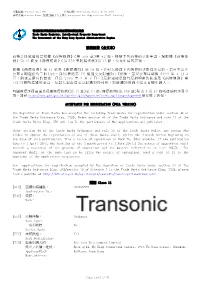

全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version)

公報編號 Journal No.: 783 公布日期 Publication Date: 06-04-2018 分項名稱 Section Name: 接納註冊 (全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version) 香港特別行政區政府知識產權署商標註冊處 Trade Marks Registry, Intellectual Property Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 接納註冊 (全文本) 商標註冊處處長已根據《商標條例》(第 559 章)第 42 條,接納下列商標的註冊申請。現根據《商標條 例》第 43 條及《商標規則》(第 559 章附屬法例)第 15 條,公布申請的詳情。 根據《商標條例》第 44 條及《商標規則》第 16 條,任何人擬就下列商標的註冊提出反對,須在本公告 公布日期起計的三個月內,採用表格第 T6 號提交反對通知。(例如,若果公布日期爲 2003 年 4 月 4 日,則該三個月的最後一日爲 2003 年 7 月 3 日。)反對通知須載有反對理由的陳述及《商標規則》第 16(2)條所提述的事宜。反對人須在提交反對通知的同時,將該通知的副本送交有關申請人。 有關商標註冊處處長根據商標條例(第 43 章)第 13 條/商標條例(第 559 章)附表 5 第 10 條所接納的註冊申 請,請到 http://www.gld.gov.hk/cgi-bin/gld/egazette/index.cgi?lang=c&agree=0 檢視電子憲報。 ACCEPTANCE FOR REGISTRATION (FULL VERSION) The Registrar of Trade Marks has accepted the following trade marks for registration under section 42 of the Trade Marks Ordinance (Cap. 559). Under section 43 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 15 of the Trade Marks Rules (Cap. 559 sub. leg.), the particulars of the applications are published. Under section 44 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 16 of the Trade Marks Rules, any person who wishes to oppose the registration of any of these marks shall, within the 3-month period beginning on the date of this publication, file a notice of opposition on Form T6. (For example, if the publication date is 4 April 2003, the last day of the 3-month period is 3 July 2003.) The notice of opposition shall include a statement of the grounds of opposition and the matters referred to in rule 16(2). -

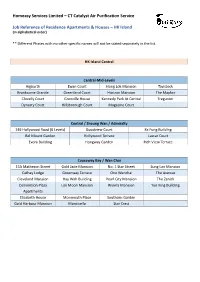

CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence

Homeasy Services Limited – CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence Apartments & Houses – HK Island (in alphabetical order) ** Different Phases with no other specific names will not be stated separately in the list. HK Island Central Central-Mid-Levels Aigburth Ewan Court Hong Lok Mansion Tavistock Branksome Grande Greenland Court Horizon Mansion The Mayfair Clovelly Court Grenville House Kennedy Park At Central Tregunter Dynasty Court Hillsborough Court Magazine Court Central / Sheung Wan / Admiralty 149 Hollywood Road (6 Levels) Goodview Court Ka Fung Building Bel Mount Garden Hollywood Terrace Lascar Court Evora Building Hongway Garden Rich View Terrace Causeway Bay / Wan Chai 15A Matheson Street Gold Jade Mansion No. 1 Star Street Sung Lan Mansion Cathay Lodge Greenway Terrave One Wanchai The Avenue Cleveland Mansion Hay Wah Building Pearl City Mansion The Zenith Convention Plaza Lok Moon Mansion Riviera Mansion Yue King Building Apartments Elizabeth House Monmouth Place Southorn Garden Gold Harbour Mansion Monticello Star Crest Happy Valley / East-Mid-Levels / Tai Hang 99 Wong Nai Chung Rd High Cliff Serenade Village Garden Beverly Hill Illumination Terrace Tai Hang Terrace Village Terrace Cavendish Heights Jardine's Lookout The Broadville Wah Fung Mansion Garden Mansion Celeste Court Malibu Garden The Legend Winfield Building Dragon Centre Nicholson Tower The Leighton Hill Wing On Lodge Flora Garden Richery Palace The Signature Wun Sha Tower Greenville Gardens Ronsdale Garden Tung Shan Terrace Hang Fung Building -

NEW SERVICE CENTRES ADDED! Tradelink Extends Its Paper Trade Declaration Service to 22 Fotomax Shops from 10 December 2018

NEW SERVICE CENTRES ADDED! Tradelink extends its Paper Trade Declaration Service to 22 Fotomax shops from 10 December 2018 Tradelink is pleased to announce extension of its Service Centre network at Fotomax to 22 shops with effect from 10 December 2018. Provide convenient paper Conveniently located in business and industry districts around trade declaration service network Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories, all these 22 designated Fotomax shops will provide Tradelink paper Trade Declaration service for customers who are unable to submit trade declarations to Government electronically. Customers can submit their paper trade declaration forms at these Tradelink Service Centres and after conversion of the paper trade declarations into electronic format, the electronic declarations will be submitted to the Government through the Tradelink platform. 22 Fotomax Shops Providing Tradelink’s Paper Trade Declaration Service Hong Kong Kowloon Wing Lok Street Cheung Sha Wan Plaza Shop 6, G/F.,Teda Bldg., Wing Lok Street, Unit 104A, Cheung Sha Wan Plaza, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 833 Cheung Sha Wan Road, Kowloon Hong Kong MTR Station Langham Place MTR Station Concession HOK 71 at Shop No.43 on Level 1, Langham Place, Hong Kong Station (Unpaid Area) 8 Argyle Street, Kowloon Shun Tak Centre Pioneer Centre Shop Unit No. 218, 2/F., Shun Tak Centre, Shop No 250 A & B, 2/F., Pioneer Centre, 200 Connaught Road, Central, Hong Kong 750 Nathan Road, Mongkok, Kowloon. Sun Hung Kai Centre Harbour City Shop No. 109-110 & 110A, Shop 4008, L4, Gateway Arcade, Harbour City, First Floor Sun Hung Kai Centre, Wanchai, Hong Kong 7-23 Canton Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kln Hopewell Centre Kowloon Station MTR Shop 311, Hopewell Centre, 183 Queen's Road East, MTR Station Concession KOW 70, Wanchai, Hong Kong Kowloon Station (Unpaid Area), Kowloon FujiFilm Studio 館 - Windsor House Whampoa Garden Shop No. -

In Hong Kong the Political Economy of the Asia Pacific

The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez- Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Series editor Vinod K. Aggarwal More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7840 Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez-Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong Fujio Mizuoka Professor Emeritus Hitotsubashi University Kunitachi, Tokyo, Japan ISSN 1866-6507 ISSN 1866-6515 (electronic) The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific ISBN 978-3-319-69792-5 ISBN 978-3-319-69793-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69793-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956132 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication.