Jheronimus Bosch-His Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

303) 578 - 0443 Baroque Ottoman(4

END TABLES RUGS CHROME & GLASS NESTING TABLES(2).........$60.00 RED CIRCLE SHAG CARPET(3)...........................$40.00 GOLD ACCENT TABLE(7).....................................$28.00 LARGE BROWN CARPET(2)...............................$100.00 MAHOGANY & TILE END TABLE(2).................$28.00 SMALL GRAY CARPET(1)......................................$64.00 WHITE END TABLE(26)..........................................$12.00 LARGE GRAY SHAG CARPET............................$100.00 BLACK END TABLE(5).............................................$12.00 EXTRA LARGE PURPLE CARPET(1)................$320.00 SLATE END TABLE(4).............................................$32.00 COWHIDE RUG(2)...................................................$80.00 BLACK & METAL END TABLE(6)......................$28.00 MEDIUM BLACK CARPET(2)...............................$40.00 SILVER BRIGHTWOOD END TABLE(10)...........$40.00 WAVE RUG(2).............................................................$40.00 GOLD BRIGHTWOOD END TABLE(10)...........$40.00 WHITEWASH END TABLE(8)..............................$24.00 CANDELABRAS GOLD FRAME END TABLE(10)..........................$28.00 BLACK CANDELABRA(25).....................................$28.00 SILVER RIVET END TABLE(10)..........................$28.00 GOLD CANDELABRA(25).......................................$28.00 SILVER STARBURST END TABLE(2)..................$28.00 RED CANDELABRA(25)..........................................$28.00 GOLD TRAY END TABLE(10).............................$20.00 SILVER CANDELABRA(25).....................................$28.00 -

Verkeersbesluit Verkeersmaatregelen Nieuwe Situatie Traverse Heeswijk-Dinther Tussen Grens Bebouwde Kom (Westzijde) En Rotonde Hulsakker (Oostzijde)

Nr. 47685 16 september STAATSCOURANT 2020 Officiële uitgave van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden sinds 1814 Verkeersbesluit verkeersmaatregelen nieuwe situatie traverse Heeswijk-Dinther tussen grens bebouwde kom (westzijde) en rotonde Hulsakker (oostzijde) BURGEMEESTER EN WETHOUDERS VAN DE GEMEENTE BERNHEZE Gelet op: artikel 18, lid 1 onder d van de Wegenverkeerswet 1994 (hierna: WVW 1994) ingevolge verkeersbesluiten worden genomen door burgemeester en wethouders voor zover zij betreffen het verkeer op wegen, welke niet in beheer zijn bij het Rijk, de Provincie of een waterschap; artikel 15, lid 1 van de WVW 1994 ingevolge de plaatsing of verwijdering van de bij algemene maatregel van bestuur aangewezen verkeerstekens en onderborden, voor zover daardoor een gebod of verbod wordt gewijzigd, geschiedt krachtens een verkeersbesluit; artikel 12, lid a van het Besluit Administratieve Bepalingen inzake het Wegbeheer (BABW), ingevolge het verwijderen, plaatsen of verplaatsen van borden A t/m G uit bijlage 1 van het RVV 1990 geschiedt krachtens een verkeersbesluit; artikel 24 van het BABW ingevolge verkeersbesluiten worden genomen na overleg met een gemachtigde van de korpschef van de politie; Overwegende dat de Hoofdstraat, Sint Servatiusstraat, Raadhuisplein, Edmundus van Dintherstraat, Den Dolvert, Brou- wersstraat, Laag-Beugt, zijn gelegen in de kern Heeswijk-Dinther en in eigendom en beheer zijn bij de gemeente Bernheze; de route Hoofdstraat, Sint Servatiusstraat, Raadhuisplein, Edmundus van Dintherstraat, Den Dolvert, Brouwersstraat, Laag-Beugt op dit moment gebruikt wordt als de doorgaande route door Heeswijk- Dinther en wordt ook de traverse genoemd; de gemeenteraad het gemeentelijke Duurzaam Mobiliteitsplan 2016-2022 heeft vastgesteld en dat hierin de traverse is aangeduid als erftoegangsweg met maximumsnelheid 30 km/uur; dat in het Duurzaam Mobiliteitsplan Bernheze 2016-2022 de focus op mensen moet liggen, toeganke- lijkheid en kwaliteit van leven i.p.v. -

The Dining Room

the Dining Room Celebrate being together in the room that is the heart of what home is about. Create a space that welcomes you and your guest and makes each moment a special occasion. HOOKER® FURNITURE contents 4 47 the 2 Adagio 4 Affinity New! dining room 7 American Life - Roslyn County New! Celebrate being together with dining room furniture from Hooker. Whether it’s a routine meal for two “on the go” 12 American Life - Urban Elevation New! between activities and appointments, or a lingering holiday 15 Arabella feast for a houseful of guests, our dining room collections will 19 Archivist enrich every occasion. 23 Auberose From expandable refectory tables to fliptop tables, we have 28 Bohéme New! a dining solution to meet your needs. From 18th Century European to French Country to Contemporary, our style 32 Chatelet selection is vast and varied. Design details like exquisite 35 Corsica veneer work, shaped fronts, turned legs and planked tops will 39 Curata lift your spirits and impress your guests. 42 Elixir Just as we give careful attention to our design details, we 44 Hill Country also give thought to added function in our dining pieces. Your meal preparation and serving will be easier as you take 50 Leesburg advantage of our wine bottle racks, flatware storage drawers 52 Live Edge and expandable tops. 54 Mélange With our functional and stylish dining room selections, we’ll 56 Pacifica New! help you elevate meal times to memorable experiences. 58 Palisade 64 Sanctuary 61 Rhapsody 72 Sandcastle 76 Skyline 28 79 Solana 82 Sorella 7 83 Studio 7H 86 Sunset Point 90 Transcend 92 Treviso 95 True Vintage 98 Tynecastle 101 Vintage West 104 Wakefield 106 Waverly Place 107 Dining Tables 109 Dining Tables with Added Function 112 Bars & Entertaining 116 Dining Chairs 124 Barstools & Counter Stools 7 132 Index & Additional Information 12 1 ADAGIO For more information on Adagio items, please see index on page 132. -

The Arts of Early Twentieth Century Dining Rooms: Arts and Crafts

THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY (Under the Direction of John C. Waters) ABSTRACT Within the preservation community, little is done to preserve the interiors of historic buildings. While many individuals are concerned with preserving our historic resources, they fail to look beyond the obvious—the exteriors of buildings. If efforts are not made to preserve interiors as well as exteriors, then many important resources will be lost. This thesis serves as a catalog of how to recreate and preserve an historic dining room of the early twentieth century in the Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco styles. INDEX WORDS: Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Dining Room, Dining Table, Dining Chair, Sideboard, China Cabinet, Cocktail Cabinet, Glass, Ceramics, Pottery, Silver, Metalworking, Textiles, Lighting, Historic Preservation, Interior Design, Interior Decoration, House Museum THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY B.S.F.C.S, The University of Georgia, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Sue-anna Eliza Dowdy All Rights Reserved THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY Major Professor: John C. Waters Committee: Wayde Brown Karen Leonas Melanie Couch Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May, 2005 DEDICATION To My Mother. -

Contents: Five Years, and Asks That We Study Them Carefully

Newsletter of the American Association for Netherlandic Studies Number 49 April 1998 the implementation of these initiatives over the next Contents: five years, and asks that we study them carefully. Association News ..........................1 You will find their text reproduced unchanged Dutch Study ...................................3 elsewhere in this newsletter. We owe a word of Conferences & Exhibitions............5 apology to any members who are not totally secure Reviews ..........................................7 reading official phraseology, but this arrived only a Publications of Interest................10 few days before the newsletter was scheduled to go Miscellaneous News ...................13 to press, and there was no time to provide a translation. ASSOCIATION NEWS In a nutshell, the points are these: A word from the AANS president 1. Taalunie fellowships. These are intended for The Nederlandse Taalunie provides generous graduate students, to enable spending a semester or support for Dutch studies in this country, helping year at an American university having a Dutch to subsidize our individual Dutch programs, program. The university is asked to commit to T.A. providing an annual subsidy to the AANS, and support for an equivalent period. making it possible to bring two guest lecturers every 2. Intensive Dutch Summer Session in the U.S. two years to our ICNS. In addition to all this, the This helps support the midwestern CIC initiative Taalunie is eager to provide focused support for the already underway (Minnesota '96 and '97, Michigan stimulation of Dutch studies in this country. In a '98, probably Indiana '99 and Wisconsin '00), as well previous issue we outlined briefly the four as others that may develop. -

Kbonieuwsbrief Maart 2020

Maart 2020 KBO-Heeswijk Ledenbezoek aan de Provincie in Den Bosch Algemene Leden Vergadering Wanneer;18 Maart a.s. Waar;in onze KBO Ruimte, Zijlstraat 1a Hoe laat;13.00 uur Let op; Verplicht aanmelden (gebruik invulstrookje) Heeft u onze nieuwe website al bekeken? U vindt er alles over onze KBO Openen via; www.kbo-heeswijk.nl KBO-Heeswijk; Onze twee nieuwe Duo-fietsen vanaf 18 maart a.s. beschikbaar Informatief en Veelzijdig Film Woensdag 11 maart, Aanvang 14.00 en 19.00 uur, KBO-Ruimte in CC Bernrode Trimclub TRIM JE FIT Vanaf maart elke woensdag aanvang 9.30 uur Lekker buiten bewegen Iedereen is welkom Verzamelen bij de receptie van Laverhof Op stap met I&Z Naar de Brabantse Kluis op 25 maart De Werkgroep Identiteit en Zingeving (I&Z) Kring Bernheze gaat op 25 maart met maximaal 30 KBO- leden naar Aarle-Rixtel. Wij worden daar om 9.45 uur Film uit de Verenigde Staten verwacht in Herberg de Brabantse Kluis. Drama / Fantasy 125 minuten Om 10.00 uur haalt zuster Madeleine ons op voor een geregisseerd door Tim Burton rondleiding van ongeveer een uur in het naastgelegen met Ewan McGregor, Albert Finney en Billy Crudup Missieklooster Heilig Bloed. Wij krijgen een inkijkje in het dagelijkse leven van de zusters en zien o.a. de kapel, de Will Bloom is de ongeloofwaardige verhalen over de eetzaal en het museum vol objecten uit Afrika. Na de avonturen van zijn vader Ed grondig beu. Een ruzie over rondleiding is er voor iedereen koffie en gebak in de Eds legendarische levensloop op de avond van zijn herberg. -

Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times

sustainability Review Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times Abdelkader T. Ahmed 1,2,* , Fatma El Gohary 3, Vasileios A. Tzanakakis 4 and Andreas N. Angelakis 5,6 1 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt 2 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University, Madinah 42351, Saudi Arabia 3 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece; [email protected] 5 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece; [email protected] 6 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Egyptian and Greek ancient civilizations prevailed in eastern Mediterranean since prehistoric times. The Egyptian civilization is thought to have been begun in about 3150 BC until 31 BC. For the ancient Greek civilization, it started in the period of Minoan (ca. 3200 BC) up to the ending of the Hellenistic era. There are various parallels and dissimilarities between both civilizations. They co-existed during a certain timeframe (from ca. 2000 to ca. 146 BC); however, they were in two different geographic areas. Both civilizations were massive traders, subsequently, they deeply influenced the regional civilizations which have developed in that region. Various scientific and technological principles were established by both civilizations through their long histories. Water management was one of these major technologies. Accordingly, they have significantly influenced the ancient world’s hydro-technologies. -

Grenzen Van Loosbroek, De “Gemeint” Van Dinther, Heeswijk En Bernheze, Volgens De Oorkonde Van Kort Voor 1233. Door N.L

Grenzen van Loosbroek, de “gemeint” van Dinther, Heeswijk en Bernheze, volgens de oorkonde van kort voor 1233. door N.L. van Dinther © 2019 capricornus Inleiding:1 In een oorkonde van kort voor 1233, beoorkondt en bevestigt Albert, heer van Kuyc, vroegere schenkingen door Albert van Dinther en anderen gedaan, en omschrijft tevens de grenzen van de communitas, gemeint, Dinther, Heeswijk en Bernheze, alsmede die van Bernhesermade en Loosbroek. 2 Albert van Dinther, een ridder van vrije geboorte, bezat een hofgoed binnen zijn eigen grond bij Bernheze, waarvan hij krachtens erfrecht het bezit verwierf. Genoemd hofgoed had verworven en houdt het recht, dat de bewoners in het bos van Dinther en Over-Aa (ultra A , d.w.z. aan de zuidelijke zijde van de rivier de Aa) hun brandhout en het hout geschikt voor het zetten van gebouwen op dat vrij-eigen goed, naar believen en in voldoende mate kunnen halen; zij mogen daar verder hun huisvarkens zonder tiend hun voedsel laten zoeken, en delen in de gemene weiden, beemden en boorden met hun mede-geërfden, en zij behoeven hiervoor noch van de heer van Kuyc, of die van Rode, noch van een van hun mede-geërfden hinder of bezwaar te vrezen. Amelrik van Heeswijk, een andere ridder hield een zelfde hofgoed met hetzelfde recht. Beide ridders hebben ieder hun hofgoed geheel en onwederroepelijk overgegeven aan het klooster van de Heilige Maagd in Berne, met instemming van Henrick onze vader. “Blijkens de beleningsoorkonde van 23 april 1301 van Dirck van Dinther door Godfried van Brabant heer van Aarschot bezat Dirck van Dinther het bos van Dinther. -

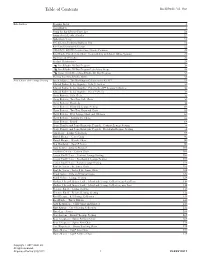

Table of Contents Knollstudio Vol

Table of Contents KnollStudio Vol. One Introduction Designer Index 3 Visual Index 5 Using the KnollStudio Price List 16 Spinneybeck Leather Grades 17 Upholstery Notes 18 f California Technical Bulletin 133 19 Knoll and Sustainable Design 22 GREENGUARD™ Certified KnollStudio Products 23 KnollStudio Finish Code Chart: Compatibility with Knoll Office Systems 25 Materials and Finishes 26 Product Maintenance 28 KnollStudio 20-Day Program 30 KnollStudio 20-Day Program Upholstery Scope 30 Items Available on KnollStudio 20-Day Program 31 Placing Your KnollStudio Order 33 Side Chairs and Lounge Seating David Adjaye : The Washington Collection for Knoll™ 34 Edward Barber & Jay Osgerby : Sofa Collection 38 Edward Barber & Jay Osgerby : Pilot by Knoll™ Lounge Collection 46 Edward Barber & Jay Osgerby : Piton™ Stools 50 Harry Bertoia : Side Chair 52 Harry Bertoia : Two-Tone Side Chair 54 Harry Bertoia : Barstools 56 Harry Bertoia : Diamond Lounge Seating 60 Harry Bertoia : Two-Tone Diamond Chair 62 Harry Bertoia : Bird Lounge Chair and Ottoman 64 Harry Bertoia : Asymmetric Chaise 66 Harry Bertoia : Bench 68 Pierre Beucler and Jean-Christophe Poggioli: Contract Lounge Seating 70 Pierre Beucler and Jean-Christophe Poggioli: Residential Lounge Seating 76 Cini Boeri : Lounge Collection 88 Marcel Breuer : Cesca Chair 92 Marcel Breuer : Wassily Chair 96 Don Chadwick : Spark Series 98 Pepe Corte´s : Jamaica Barstool 102 Jonathan Crinion : Crinion Chair 104 Joseph Paul D’Urso : Contract Lounge Seating 106 Joseph Paul D’Urso : Residential Lounge Seating 110 -

The Ruusbroec Institute and Its Library Establishment

The Ruusbroec Institute and its library FRANS HENDRICKX Establishment The Ruusbroec Institute Library developed alongside the vision of its founders, led by Father Stracke († 1970), whose aim was to study the history of spirituality in the Low Countries. When Stracke received his doctorate in Germanic Philology from Leuven in 1903-1904 with a thesis on the lives of Christina of Sint-Truiden and Lutgardis of Tongeren, his mentor Louis Scharpé († 1935) encouraged him in his ambition to establish the Bibliotheca Ascetica Patrum Societaties Jesu Provinciae Flandrensis . This central library of the Order would provide the necessary resources and study materials for conducting research into the spirituality of the Jesuit Society in the Low Countries between the Counter Reformation and the eighteenth century. This was because the Bibliographie de la Compagnie de Jésus , assembled in twelve successive parts by Augustin and Alois De Backer († 1873 and 1883 respectively) and Carlos Sommervogel († 1902), was deemed to be in need of expansion and improvement with regard to the Jesuit writers of both the southern and northern Low Countries. However, since ascetic and mystical writings had often been overlooked and treated disparagingly in Dutch literary history books, and in light of the emancipation of Arm Vlaanderen (Poor Flanders) – Stracke's remarkable speech to the Katholieke Vlaamsche Wacht in Borgerhout on 13 November 1913 – the original plan, which was never actually realized, gradually transformed into a more general exploration of the Low Countries' spiritual history, beginning in the Middle Ages. Three Jesuits, all Germanics graduates of the Leuven Alma Mater – Desideer A. Stracke († 1970), Jozef Van Mierlo († 1958) and Leonce Reypens († 1972) – were the founding scholars of a new working community formed in 1925. -

N279 Veghel - ’S-Hertogenbosch Afgesloten Voor Werkzaamheden

N279 Veghel - ’s-Hertogenbosch afgesloten voor werkzaamheden ’s-Hertogenbosch, 6 maart 2015 - De werkzaamheden voor de verbreding van de N279 tussen ’s-Hertogenbosch en Veghel gaan dit voorjaar van start. Vooruitlopend daarop worden de komende week al extra opstelstroken gerealiseerd voor verkeer vanuit Veghel richting ’s-Hertogenbosch om de doorstroming van het verkeer al meteen te verbeteren. Bij de aansluitingen met Heeswijk-Dinther, Middelrode en Berlicum krijgt het verkeer op de N279 extra ruimte om het kruispunt te passeren. Daarnaast worden de verkeerslichten aangepast. Om deze werkzaamheden mogelijk te maken, wordt de N279 in maart een weekend deels afgesloten voor verkeer. De werkzaamheden voor deze ‘quick wins’ worden in de week van 9 tot en met 16 maart uitgevoerd. Van maandag 9 tot vrijdag 13 maart vinden er werkzaamheden in de avond en nacht plaats. Verkeer wordt in die nachten bij de aansluitingen begeleid door verkeersregelaars. Van vrijdag 13 maart 21.00 uur tot en met maandag 16 maart 6.00 uur is de N279 afgesloten tussen de kruising met de op- en afrit van de A50 en de kruising met de Beusingsedijk. Vanaf de Beusingsedijk is de oprit in de richting van ’s-Hertogenbosch open. Het verkeer wordt via borden omgeleid. De N279 van ‘s- Hertogenbosch naar Veghel is wel open voor verkeer. De werkzaamheden hebben geen effect voor fietsers. Omleidingsroute Het verkeer wordt tijdens de werkzaamheden omgeleid via de A50, A59 en A2. Verkeer richting Heeswijk-Dinther rijdt via de N622 (Schijndel) en verkeer van Heeswijk-Dinther richting Den Bosch rijdt via de dorpen Middelrode en Berlicum. Meer informatie over de verbreding van de N279 en de geplande werkzaamheden is te vinden op www.brabant.nl/n279 en www.haalmeeruitdeweg.nl. -

Medieval Furniture

Medieval Furniture A class offered at Pennsic XXX by Master Sir Stanford of Sheffield August 2001ce ©2001 Stanley D. Hunter, all right reserved Medieval Furniture Part I - Furniture Use and Design.............................................................................................1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................1 The Medieval House and Furnishings..................................................................................2 Documentary Evidence of Furnishings ............................................................................2 Furniture Construction Techniques ..................................................................................3 Introduction.......................................................................................................................5 Armoires ...............................................................................................................................6 Buffets and Dressoirs............................................................................................................6 Beds ......................................................................................................................................7 Chests....................................................................................................................................7 Seating..................................................................................................................................9