NSW Lighthouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model Of

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model of Creativity through documentary video and online practice Susan Kerrigan BArts (Comm Studies) (UoN), Grad Cert Practice Tertiary Teaching (UoN) A creative work thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication & Media Arts University of Newcastle, June 2011 Declarations: Declaration 1: I hereby certify that some elements of the creative work Using Fort Scratchley which has been submitted as part of this creative PhD thesis were created in collaboration with another researcher, Kathy Freeman, who worked on the video documentary as the editor. Kathy was working at the Honours level from 2005 to 2006 and I was her Honours Supervisor. Kathy was researching the creative role of the editor, her Honours research was titled Expanding and Contracting the role of the Editor: Investigating the role of the editor in the collaborative and creative procedure of documentary film production (Freeman, 2007). While Kathy’s work dovetailed closely with my own work there was a clear separation of responsibilities and research imperatives, as each of our research topics was focussed on the creative aspects of our different production crew roles. Declaration 2: I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis contains one journal publication and three peer-reviewed published conference papers authored by myself. Kerrigan, S. (2010) Creative Practice Research: Interrogating creativity theories through documentary practice TEXT October 2010. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, Special Issue Number 8, from http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue8/content.htm Kerrigan, S. (2009) Applying creativity theories to a documentary filmmaker’s practice Aspera 2009 - Beyond the Screen: Retrieved from http://www.aspera.org.au/node/40 Kerrigan, S. -

SIMS Foundation Newsletter September 2014

Newsletter September 2014 Fantasea Harbour Hike 2014 Several weeks of wet conditions did not dampen the spirits of hikers in the Fantasea Harbour Hike event held on Father’s Day. Even the weather participated with a bright sunny day enjoyed by all after some early morning rain. These testimonials show just what a great day was had by participants: Sarah: “I just wanted to contact and say how much of a brilliant day this was! Despite the rain, the hike was beautiful (albeit muddy) and a lot of fun. The research that this hike is funding is so amazing and I will definitely be participating next year! A really fun morning out with family and friends!” Imelda: “I just wanted to say how much Fred and I enjoyed the SIMS Harbour Hike. It was so well organised. The volunteers along the route, all with friendly Dr. Emma Thompson showing how research is done on Sydney smiles on their faces, did a great job answering our questions however Rock Oysters. Hikers lined up to have a go at extracting the trivial, nothing was any trouble. The Fantasea Marine Festival was just so haemolymph (blood) of an oyster. good and made us aware of the importance of preserving our fragile marine environment and supporting the talented work and research being done by SIMS. We had such a lovely day and all being well we will be doing it next year.” We are most grateful to Fantasea Adventure Cruising who are the presenting sponsor of this event. We also wish to thank our community sponsor, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Services and our media partner, Radio 2UE together with all of our community partners including Mosman and North Sydney Councils, Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, National Parks Association of NSW, Taronga Zoo, Bright Print Group and NSW Police. -

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

The Architecture of Scientific Sydney

Journal and Proceedings of The Royal Society of New South Wales Volume 118 Parts 3 and 4 [Issued March, 1986] pp.181-193 Return to CONTENTS The Architecture of Scientific Sydney Joan Kerr [Paper given at the “Scientific Sydney” Seminar on 18 May, 1985, at History House, Macquarie St., Sydney.] A special building for pure science in Sydney certainly preceded any building for the arts – or even for religious worship – if we allow that Lieutenant William Dawes‟ observatory erected in 1788, a special building and that its purpose was pure science.[1] As might be expected, being erected in the first year of European settlement it was not a particularly impressive edifice. It was made of wood and canvas and consisted of an octagonal quadrant room with a white conical canvas revolving roof nailed to poles containing a shutter for Dawes‟ telescope. The adjacent wooden building, which served as accommodation for Dawes when he stayed there overnight to make evening observations, was used to store the rest of the instruments. It also had a shutter in the roof. A tent-observatory was a common portable building for eighteenth century scientific travellers; indeed, the English portable observatory Dawes was known to have used at Rio on the First Fleet voyage that brought him to Sydney was probably cannibalised for this primitive pioneer structure. The location of Dawes‟ observatory on the firm rock bed at the northern end of Sydney Cove was more impressive. It is now called Dawes Point after our pioneer scientist, but Dawes himself more properly called it „Point Maskelyne‟, after the Astronomer Royal. -

E-Book Code: REAU1036

E-book Code: REAU1036 Written by Margaret Etherton. Illustrated by Terry Allen. Published by Ready-Ed Publications (2007) © Ready-Ed Publications - 2007. P.O. Box 276 Greenwood Perth W.A. 6024 Email: [email protected] Website: www.readyed.com.au COPYRIGHT NOTICE Permission is granted for the purchaser to photocopy sufficient copies for non-commercial educational purposes. However, this permission is not transferable and applies only to the purchasing individual or institution. ISBN 1 86397 710 4 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012 12345678901234 5 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 -

Spring 2013 by DESIGN Sydney’S Planning Future

spring 2013 BY DESIGN Sydney’s planning future REVIEW Reflections on Public Sydney: Drawing The City DRAWING ATTENTION The language of architecture DESIGN PARRAMATTA Reinvigorating public places In the public interest Documenting, drawing and designing a city 7. Editor Laura Wise [email protected] Editorial Committee Chair Contents Shaun Carter [email protected] President’s message Editorial Committee 02 Noni Boyd [email protected] Callantha Brigham [email protected] 03 Chapter news Matthew Chan [email protected] Art direction and design 12. Opinion: Diversity - A building block for Jamie Carroll and Ersen Sen innovation Dr Joanne Jakovich and Anita leadinghand.com.au 06 Morandini Copy Editor Monique Pasilow Managing Editor Our biggest building project Joe Agius Roslyn Irons 07 Advertising [email protected] Subscriptions (annual) Review: Reflections on Public Sydney Andrew Five issues $60, students $40 12 Burns, Rachel Neeson and Ken Maher [email protected] Editorial & advertising office Tusculum, 3 Manning Street Drawing the public’s attention: The Language of Potts Point NSW 2011 (02) 9246 4055 20. 16 architecture Adrian Chan, David Drinkwater and ISSN 0729 08714 Aaron Murray Published five times a year, Architecture Bulletin is the journal of the Australian Institute of Architects, James Barnet: A path through his city NSW Chapter (ACN 000 023 012). 18 Dr Peter Kohane Continuously published since 1944. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in articles and letters published in From the Government Architect: Architecture Bulletin are the personal 19 views and opinions of the authors of Non-autonomous architecture Peter Poulet these writings and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Institute and its officers. -

1.0 Introduction 2.0 Background 3.0 Existing Waterway Navigation and Usage

Hanson Construction Materials Pty Ltd ABN 90 009 679 734 Level 18 2 ‐ 12 Macquarie Street Parramatta NSW 2150 Tel +612 9354 2600 Fax +612 9325 2695 www.hanson.com.au 1.0 Introduction This report is prepared in relation to a State Significant Development Application (SSDA) for an Aggregate Handling and Concrete Batching facility at Glebe Island (SSD 8854). Glebe Island currently operates as a working industrial port under the management of Ports Authority of NSW (Port Authority). The aggregate handling and concrete batching facility is proposed adjacent to the existing Glebe Island Berth 1 (GLB1) terminal. Aggregate is proposed to be delivered by ship to the GLB1 berth at Glebe Island. This report provides information relating to marine traffic, navigation and safety and outlines any potential maritime safety issues, and measures required to minimise and mitigate any impacts resulting from the proposed development. 2.0 Background The SSDA was submitted to the Department of Planning and Environment (DP&E) in March 2018 and subsequently placed on formal public exhibition for 5 weeks, between 11 April 2018 and 15 May 2018. On 20 August 2018, a Request for Additional Information (RFI) was issued by the DP&E. This report responds to the additional information sought in relation to the maritime traffic, safety and navigation impact assessment (Issues 30 – 32 under Schedule 1) for the new facility at Glebe Island. For the purposes of this SSDA, this statement provides a preliminary navigation impact assessment and outlines the general processes and guidelines in place that governs marine traffic flow within the context of the site at GLB1, Glebe Island and Sydney Harbour. -

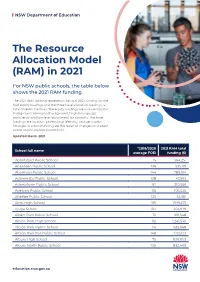

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Australia's National Heritage

AUSTRALIA’S australia’s national heritage © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts ISBN: 978-1-921733-02-4 Information in this document may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Heritage Division Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Email [email protected] Phone 1800 803 772 Images used throughout are © Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and associated photographers unless otherwise noted. Front cover images courtesy: Botanic Gardens Trust, Joe Shemesh, Brickendon Estate, Stuart Cohen, iStockphoto Back cover: AGAD, GBRMPA, iStockphoto “Our heritage provides an enduring golden thread that binds our diverse past with our life today and the stories of tomorrow.” Anonymous Willandra Lakes Region II AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL HERITAGE A message from the Minister Welcome to the second edition of Australia’s National Heritage celebrating the 87 special places on Australia’s National Heritage List. Australia’s heritage places are a source of great national pride. Each and every site tells a unique Australian story. These places and stories have laid the foundations of our shared national identity upon which our communities are built. The treasured places and their stories featured throughout this book represent Australia’s remarkably diverse natural environment. Places such as the Glass House Mountains and the picturesque Australian Alps. Other places celebrate Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture—the world’s oldest continuous culture on earth—through places such as the Brewarrina Fish Traps and Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry. -

The Shorebirds of Port Stephens Recent and Historical Perspectives

THE SHOREBIRDS OF PORT STEPHENS RECENT AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES A D Stuart HBOC Special Report No. 2 © May 2004 THE SHOREBIRDS OF PORT STEPHENS RECENT AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES A D Stuart May 2004 HBOC Special Report No. 2 Cover Photo: Eastern Curlew Numenius madagascariensis (Photographer: Chris Herbert). The Eastern Curlew is a common and abundant shorebird of Port Stephens. At least 600 birds are present each summer and many of the immature birds remain through the winter months. Port Stephens is an internationally significant habitat for the species. This report is copyright. Copyright for the entire contents is vested in the author and has been assigned to Hunter Bird Observers Club. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without prior written permission. Enquiries should be made to Hunter Bird Observers Club. © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc P.O. Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Australia http://users.hunterlink.net.au/hboc/home.htm Price: $20 HBOC Special Reports 1. Birds of Ash Island, A D Stuart, December 2002 2. The Shorebirds of Port Stephens. Recent and Historical Perspectives, A D Stuart, May 2004 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. HIGH TIDE SURVEYS AT SWAN BAY (WORIMI NATURE RESERVE) 3 2.1. Summary 3 2.2. Survey Methodology 6 2.3. Discussion 7 2.4. Acknowledgements 8 3. PORT STEPHENS HIGH TIDE SURVEY 8 FEBRUARY 2004 12 3.1. -

The Permanent Walk Booklet Update

1 2 THE OLD AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURAL COMPANY KARUAH TO TAHLEE WALK BOOKLET (Revised for 2015) We acknowledge and recognise the Worimi people on whose land we walk. GENERAL INTRODUCTION WHY WALK? Once every year, Karuah residents and friends walk the 5 kilometres or so from Karuah to Tahlee along the Old AACo Road. It only happens once a year because the road crosses Yalimbah Creek and the bridge that used to cross the creek has gone. In the late 1950s, the bridge which had been built under the direction of Robert Dawson in 1826 was burnt down by persons unknown. At that stage, the bridge was more than 130 years old, a remarkable age for a wooden bridge. Up to that point residents of the two villages had travelled back and forth on a daily basis. From then on, they were forced to take the current route which is 14 kilometres long. So, every year for the last five years, a local oyster farmer has offered an oyster barge to carry people over the creek and around 150 people re-enact the trip from village to village. Karuah Progress association hosts the day which includes a light lunch, guides, afternoon tea and an inspection of historic Tahlee House and a bus ride back to Karuah via the new route as well as a photocopied version of this booklet. TAHLEE AND KARUAH – IN THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY: In 1825 when the Australian Agricultural Company was formed, 10,000 shares were offered at one hundred pounds per share and they were snapped up by the rich and famous. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Reading the City, Walking the Book: Mapping Sydney’s Fictional Topographies Susan M. King A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English August 2013 Preface I hereby declare that, except where indicated in the text and footnotes, this thesis contains only my own original work.